| Citation: | Quanan Zheng, Lingling Xie, Xuejun Xiong, Xiaomin Hu, Liang Chen. Progress in research of submesoscale processes in the South China Sea[J]. Acta Oceanologica Sinica, 2020, 39(1): 1-13. doi: 10.1007/s13131-019-1521-4 |

The ocean water motions always contain contributions from the multiscale dynamic processes. Among them, the mesoscale and large scale motions with the characteristic horizontal scale larger than 200 km contain about 90% of the kinetic energy of the ocean. Therefore, these processes comprise a research focus of physical oceanography and geophysical fluid dynamics. On the other hand, the small-scale ocean motions with the characteristic horizontal scale smaller than 1 km, typically the sea surface waves, are closely associated with human activities in the ocean, therefore, were a research focus of pioneering oceanographers. However, the ocean motions with the characteristic horizontal scales between the two, so called submesoscale, were not paid attentions until late 1980s. Literature hunting by this study finds that the earliest article using term “submesoscale” to define an ocean vortex train was McWilliams (1985). Later, the term was used to explain vortex observations in the Beaufort Sea north of Alaska by D’Asaro (1988).

The situation has been changed since the beginning of the 21st century. The recent research results revealed that the upper-ocean submesoscale processes determine the equilibrium state of the upper ocean through the turbulent kinetic energy cascade and energy dissipation (Ferrari and Wunsch, 2009; Qiu et al., 2017; McWilliams, 2017). They also affect the mixed layer development and upper-ocean thermal anomaly (Lapeyre and Klein, 2006; Capet et al., 2008a), and the CO2 uptake, nutrient supply, phytoplankton production/subduction and biogeochemistry (Mahadevan and Archer, 2000; Lévy et al., 2001, 2012; Zhong and Bracco, 2013). Capet et al. (2008a) investigated the near-surface submesoscale currents at an intermediate scale—approximately defined by a horizontal scale of O(10) km, less than the first baroclinic deformation radius; a vertical scale of O(10) m, thinner than the main pycnocline; and a time scale of O(1) d, comparable to a lateral advection time for submesoscale feature using numerical modeling. Capet et al. (2008b) investigated submesoscale activity over the Argentinian shelf using numerical modeling and pointed out that submesoscale activity is widespread in the upper ocean. Mensa et al. (2013) studied seasonality of the submesoscale dynamics in the Gulf Stream region with the hybrid coordinate ocean model (HYCOM). Qiu et al. (2014) studied seasonal variability of mesoscale and submesoscale eddies along the North Pacific Subtropical Countercurrent using high resolution modeling and satellite altimetry product. Callies et al. (2015) presented observational evidence that submesoscale flows undergo a seasonal cycle in the surface mixed layer. Gula et al. (2016) studied topographic generation of submesoscale centrifugal instability and energy dissipation. They suggested that topographic generation of submesoscale flows potentially provides a new and significant route to energy dissipation for geostrophic flows. Sasaki et al. (2017) investigated submesoscale processes in subarctic regions. They found an inverse cascade of energy towards larger scale, i.e., submesoscale impact seems to strengthen mesoscale eddies that become more coherent and not quickly dissipated. Lévy et al. (2018) studied the role of submesoscale currents in structuring marine ecosystems using observations and models. Liu et al. (2018a) studied the influence of mesoscale and submesoscale circulation on sinking particles in the northern Gulf of Mexico using three-dimensional velocity fields generated by a regional ocean model to backtrack the trajectories of sinking particles from a depth of about 1 000 m. Taylor et al. (2018) observed submesoscale Rossby waves along the Antarctic circumpolar current. Zhang et al. (2019) found that the balanced submesoscale ageostrophic processes are important for the surface chlorophyll variances. Hence, the above progresses indicate that submesoscale dynamics has been becoming a prosperous field in the oceanographic research.

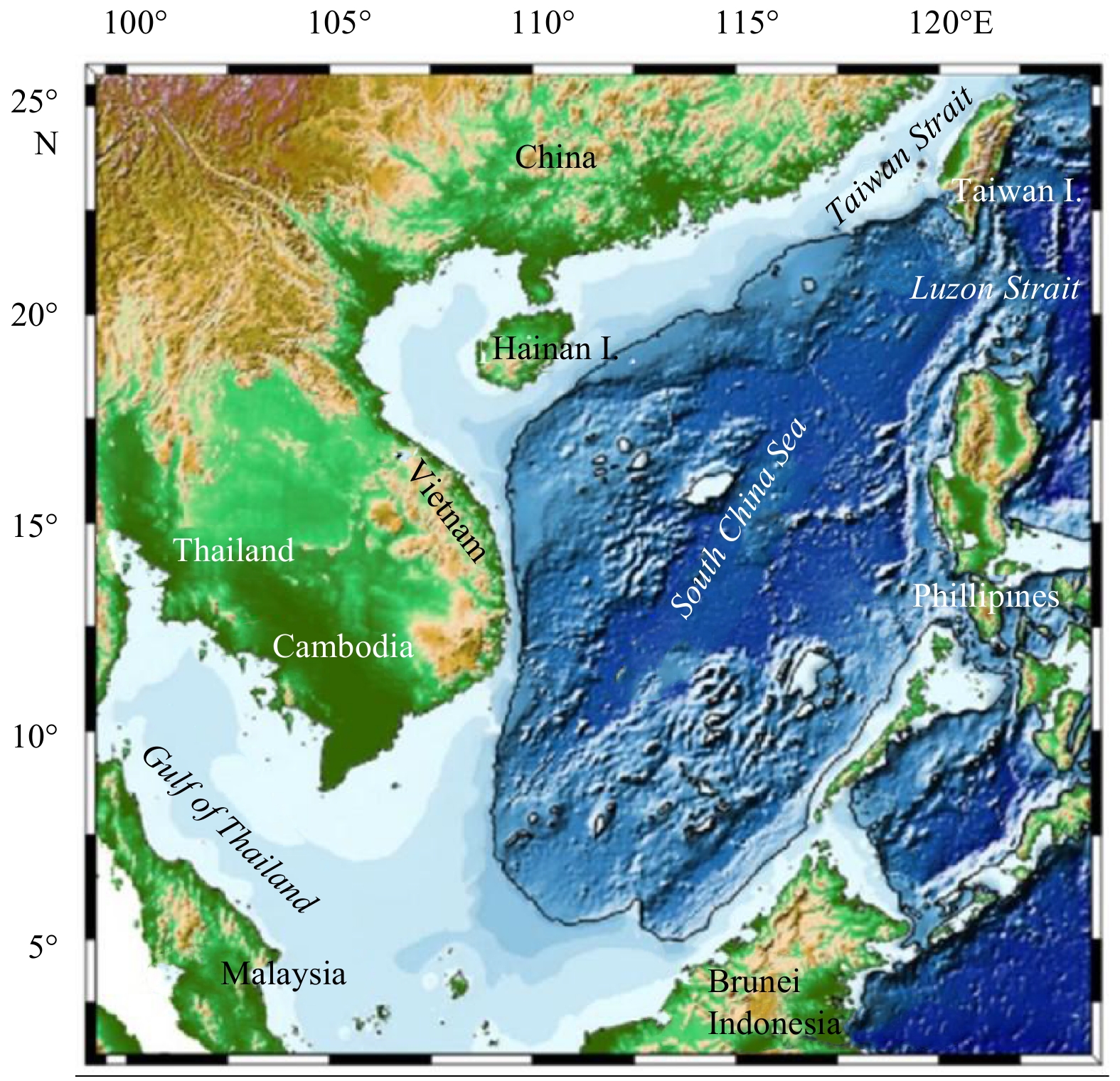

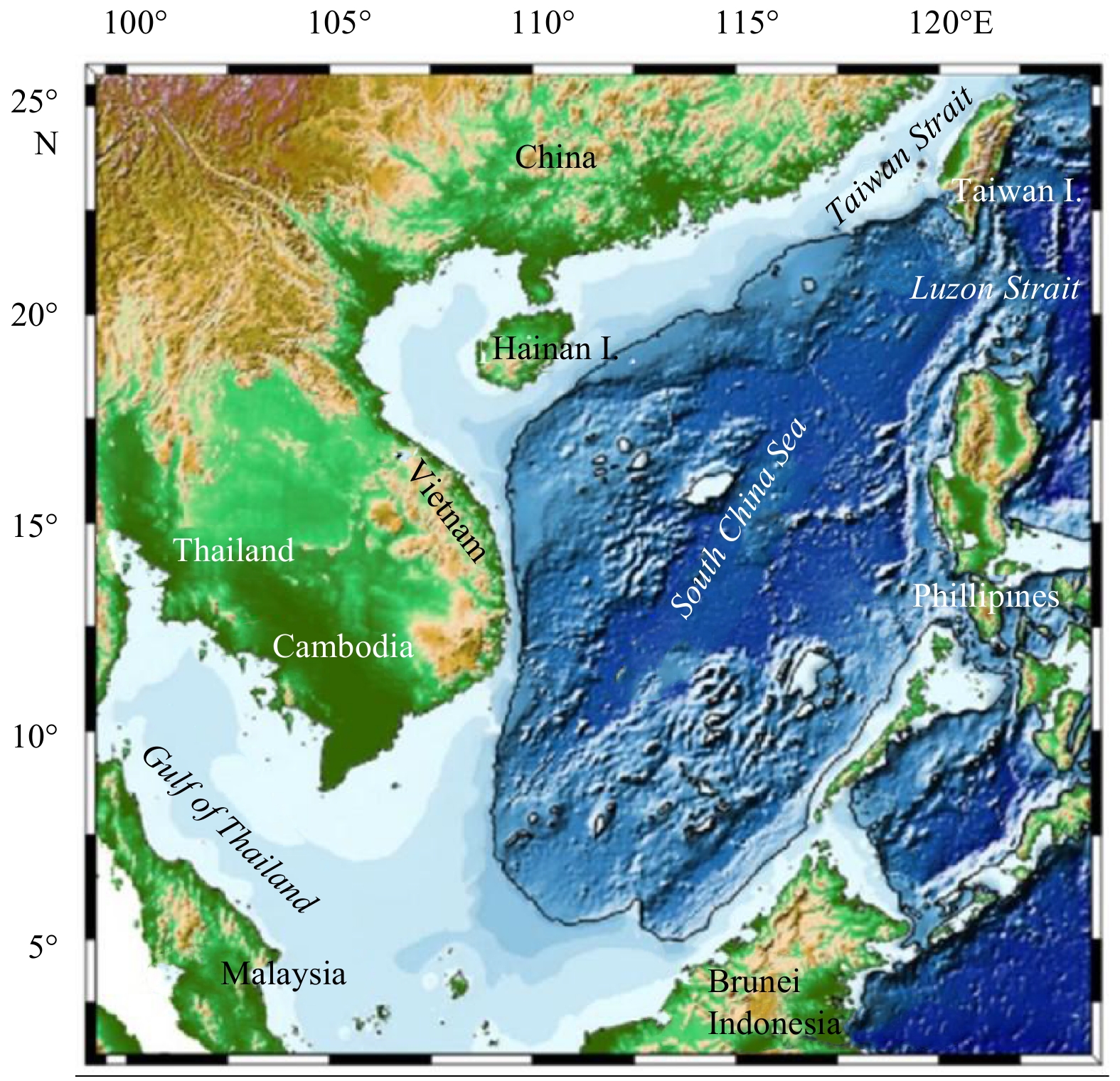

In the case of the South China Sea (SCS), previous investigations have revealed that it is a dynamically active sea (Zheng et al., 2006; Hu et al., 2019). Particularly, there are broadly distributed mesoscale eddies (Wang et al., 2003; Nan et al., 2011; Zheng et al., 2014, 2017; Xie and Zheng, 2017; Xie et al., 2018; He et al., 2018) and strong internal waves (Ramp et al., 2004, 2010; Buijsman et al., 2010; Zhao et al., 2004; Zheng et al., 2007, 2017; Wang et al., 2012; Bai et al., 2017). This is attributed to the following three major mechanisms: (1) semi-enclosed marginal sea geography and complex bottom topography as shown in Fig. 1, (2) strong disturbances from the Pacific penetrating the Kuroshio and the Luzon Strait entering the SCS (Hu et al., 2001; Qu et al., 2004; Zhuang et al., 2010; Zheng et al., 2011, 2019; Xie et al., 2016), and (3) seasonally reversing East Asia monsoon (Ho et al., 2000; Hu et al., 2000; Li et al., 2015, 2016; Cao et al., 2017). These dynamic conditions favor the generating of submesoscale flow structures in the form of small eddies, density fronts and filaments, topographic wakes and persistent coherent vortexes at the surface and throughout the interior (McWilliam, 2016). In the other words, there must be abundant submesoscale processes in the SCS. Li et al. (2011) analyzed 30 years of the satellite-tracked Lagrangian drifter data from 1979 to 2010 in the northern South China Sea (NSCS). 100% of total detected 1972 eddies have the radii smaller than 150 km, implying that the eddy fields in the NSCS may be treated as submesoscale eddy fields. The earliest article using term “submesoscale” to define the ocean vortex train in the SCS was Zheng et al. (2008). At present, more scientists are interested in this recently discovered realm. This paper overviews recent progress in research of submesoscale dynamics in the SCS, particularly in recent five years.

Up to now, there are not commonly accepted criteria for defining an ocean phenomenon as a submesoscale process. Here we list definitions used by the authors of published papers collected till 2018 in Table 1.

| Author(s) (year) | Horizontal scale/km | Vertical scale/m | Time scale/d |

| McWilliams (1985) | < first baroclinic radius of deformation | ||

| Capet et al. (2008a) | O(10) | O(10) | O(1) |

| Ferrari and Wunsch (2009) | 10–150 | ||

| Liu et al. (2010a) | O(1) | ||

| Callies and Ferrari (2013) | 1–200 | ||

| Callies et al. (2015) | 1–100 | ||

| McWilliams (2016) | 0.1–10 | 10–1 000 | hours-day |

| Sasaki et al. (2017) | 16–50 | ||

| Qiu et al. (2017) | 10–150 | ||

| Zheng (2017) | 1–200 | ||

| Zhong et al. (2017) | Rossby number O(1) | ||

| Renault et al. (2018) | 0.1–10 | ||

| Li et al. (2018) | O(0–10) | O(1) | |

| Dong and Zhong (2018) | Rossby number O(1) |

In this review paper, we adopt all definitions of submesoscale ocean processes given by the authors of reviewed articles. In the cases without definite definitions, we use two criteria to determine the submesoscale: either (1) spatial scale definition, 1–100 km, here the scale of 100 km is an estimate of the Rossby deformation radius in the SCS, or (2) dynamic scale definition, Rossby number R0, 0.5–10.

Following the above criteria, we further categorize the submesoscale ocean processes into sub-categories according to similarities of dynamic features of the processes. The results are listed in Table 2.

| Sub-categories | Phenomena/processes | Scales |

| Submesoscale waves | long internal waves | wavelength: 1–5 km, crest line: 10–200 km, |

| R0: 2–10 at 20°N | ||

| Internal tide* | Mode-1 M2: wavelength ~150 km, R0~0.5 | |

| near inertial waves* | wavelength: 10–20 km, R0 = O(1) | |

| instability/shear waves | ||

| Submesoscale vortexes | small eddies* | R0 = O(1) |

| coherent vortex train* | R0 = O(1) | |

| spiral train* | R0 = O(1) | |

| topographic wakes | ||

| Submesoscale shelf processes | small estuary plumes | R0 = O(0.5) |

| front* | frontal widths: 10–50 km | |

| horizontal wavelength: 20–40 km | ||

| vertical circulation* | ||

| offshore jet/filament | R0 = O(0.5) | |

| Submesoscale turbulence | Modeled submesoscale turbulence* | R0 = O(1) |

| Note: * Reviewed in this paper. | ||

In the SCS, the internal waves (IWs) appear as a horizontally two-dimensional structure: crest lines with horizontal lengths of O(10–200) km and linear waves with wavelength scales of O(1–5) km. The characteristic speed is 0.5 m/s (Zheng, 2017). The Rossby number is O(2–10) if using the wavelength scales as the horizontal length scales and 20°N as a characteristic latitude. Strong IWs are an outstanding feature of regional oceanography of the SCS. Thus, it has been a continuously productive research field as reviewed by Zhao et al. (2014) and Zheng (2017).

Studies of evolution of the internal solitary waves (ISWs) in the SCS obtain new progresses. Huang et al. (2014) observed entire evolution process of ISWs west of the Luzon Strait using mooring array data. Li et al. (2013) and Bai et al. (2017) observed ISW refraction and reflection near the Dongsha Atoll. Dong et al. (2016) observed evidence for existence of the eddy-induced mode-2 ISWs based on two SAR images acquired in 2001.

An important new finding of the IWs in the NSCS was reported by Chen et al. (2018). Using mooring data observed on the NSCS continental slope, they found a new type of diurnal ISWs with a re-appearance period (RP) of about 23 h. As shown in Fig. 2, the newly found type-c ISWs are distinct from types-a and -b ISWs characterized by the RPs of about 24 h and 25 h (Ramp et al., 2004, 2010). The mechanisms for the differential RPs, however, still remain unclear.

The strong internal tides in the SCS are generated by interaction of the tidal current and the bottom topography at the Luzon Strait. Dependence of the strong IWs west of the Luzon Strait upon the internal tides has been a research hot spot since early 2000s (Zhao et al., 2004; Lien et al., 2005; Farmer et al., 2011). Zhao (2014) derived the internal tide radiation patterns originating from the Luzon Strait from the sea surface height data of multiple satellite altimeters, showing the radiation patterns of M2 internal tides in the SCS as shown in Fig. 3a. Coherence of horizontal distribution of IW packets observed from the synthetic aperture data (SAR) images with the energy fluxes of the northwestward Mode-1 M2 internal tides is shown in Fig. 3b. One can see that these results provide solid evidence for the scenarios that the ISWs in the northeastern SCS deep basin originate from M2 internal tides at the Luzon Strait, and the diurnal internal tides play a secondary role by modifying the IW generation (Helfrich and Grimshaw, 2008; Buijsman et al., 2010; Li and Farmer, 2011; Zhang et al., 2011). From Fig 3a, we derive that the wavelength of Mode-1 M2 internal tide is 135 km. Its Rossby number is O(0.5).

Zhao et al. (2018) observed the first mode internal tides in the northwestern SCS using five pressure-recording inverted echo sounders along a section between the continental shelf break in the north and Xisha Islands in the south. Their results indicate that diurnal component is affected by that propagating from the Luzon Strait, while semidiurnal component is primarily generated locally from the continental shelf break.

According to the definition, the Rossby number of the near inertial oscillations (NIOs)/waves (NIWs) is near O(1) and their horizontal scale is O(10–20) km (Zheng, 2018). Therefore, the NIWs belong to the submesoscale processes. The history of the research of NIWs in the SCS is only a little longer than ten years (Liang et al., 2005; Zhu and Li, 2007; Alford, 2008). Previous investigations have revealed that the NIWs in the SCS are mainly generated by two mechanisms: parametric subharmonic instability (PSI) occurring at ~20°N (Alford, 2008; Xie et al., 2011) and wind-forced (Sun et al., 2011a, 2011b; Chen et al., 2013; Xu et al., 2013: Zhang et al., 2014b).

Since 2010, typhoon-forced NIWs have been a research focus for majority of research projects. For example, the South China Sea Internal Wave Experiment (SCSIWEX) project 2010–2011 provided very good mooring array data sets for such research. Guan et al. (2014) examined the upper ocean thermal and dynamic response to typhoon Megi 2010 with the presence of strong internal tides using the SCSIWEX data. They found that the NIWs under typhoon Megi 2010 were relatively weak and quickly damped within a short decay time scale of two inertial periods, compared with the NIO response to hurricane Frances with the same category 3 in the Atlantic. Yang and Hou (2014) investigated the NIWs in the wake of typhoon Nesat 2011 in the NSCS using SCSIWEX data sets. They found that the second mode of the NIWs has a dominant variance contribution of 81%, and the corresponding horizontal phase velocity and wavelength reach 3.50 m/s and 420 km, respectively.

Cao et al. (2018) reported five burst events of NIWs in the NSCS during the period from August 2010 to April 2011 using SCSIWEX mooring data as shown in Fig. 4. Among these NIW evens, three were induced by typhoons Lionrock, Meranti and Megi in 2010. The NIWs show various intensities and structures at three moorings. This is attributed to differences of typhoon characteristics, mooring measuring ranges, distances between typhoon centers and moorings, as well as local conditions. They found that the NIWs generated by weaker typhoon Meranti were stronger than that by stronger typhoon Megi and attributed to the higher translation speed of Meranti as shown in Fig. 5.

In addition to typhoon-induced NIWs, Cao et al. (2018) observed two NIW burst events in December 2010 and March 2011 at mooring station UIB6. Ruled out the local winds, lateral propagation and parametric subharmonic instability as the causes of these NIW burst events, they suggested that the real mechanisms remain unknown. They found that these NIWs exhibit different features from typhoon-induced NIWs. First, these NIWs have larger vertical wave numbers and smaller wavelengths than the typhoon-induced NIWs. Second, these NIWs cause intense shear in deep water, whereas intense shear of typhoon-induced NIWs mainly exists in the upper ocean (approximately 150–200 m). These no-typhoon and no-PSI NIW events need to be further clarified if they are generated by the third type of external forcing or internal wave-wave interaction.

Chen et al. (2015) observed features of near-inertial motions on the NSCS shelf (60 m deep) under the passage of two typhoons Nangka and Linfa in summer 2009. They found that there are two peaks in spectra at both sub-inertial and super-inertial frequencies. The super-inertial energy maximizes near the surface, while the sub-inertial energy maximizes at a deeper layer of 15 m. The sub-inertial shift of frequency is induced by the negative background vorticity. The super-inertial shift is probably attributed to the NIWs propagating from higher latitudes.

Shu et al. (2016) observed generation of near-inertial oscillations by summer monsoon onset over the SCS with ADCP mooring data in 1998 and 1999. The near-inertial current speed reached 0.25 m/s, comparable to that induced by tropical storms in the same area, although the wind speed (~10 m/s) of the monsoon onset was much lower than that of typical tropical storms. Their analysis suggests that the shallow mixed-layer (< 30 m) and the abrupt changes in wind speed and direction resulting from the summer monsoon onset are responsible for developing the near-inertial current. The generated NIOs could be enhanced by a warm eddy appearing during the monsoon onset in the central SCS.

Xiao et al. (2016) examined near-inertial variability of the meridional overturning circulation in the SCS (SCSMOC) using a global (1/12)° ocean reanalysis data. Based on the wavelet analysis and power spectra, they found that deep SCSMOC has a significant near-inertial band. The maximum amplitude of the near-inertial signal is nearly 4×106 m3/s. The spatial structure of the signal features regularly alternate counterclockwise and clockwise overturning cells. They also found that the near-inertial signal of SCSMOC mainly originates from the region near the Luzon Strait and propagates equatorward at a speed of 1–3 m/s. Further analyses suggest that the near-inertial signal in SCSMOC is triggered by high-frequency wind variability near the Luzon Strait, where geostrophic shear always exists due to the Kuroshio intrusion.

Liu et al. (2018b) investigated nonlinear wave-wave interaction between the NIWs and diurnal tides (DTs) after passages of nine typhoons over the Xisha Islands in the NSCS using three years of mooring data. They found that a harmonic wave fD1 with a frequency equal to the sum of frequencies of NIWs and diurnal tide D1 was generated via nonlinear interaction between the two. The fD1 wave is mainly concentrated in the subsurface layer and induced by the first component of the vertical nonlinear momentum term, the product of the vertical velocity of DT and vertical shear of near-inertial current.

The early work on submesoscale vortex train in the SCS can be traced back to Zheng et al. (2008). Recently Liu et al. (2015) studied submesoscale (they called small-scale) processes off the Vietnam coast in the western SCS in summer using high-resolution (300 m) ocean color data of the Medium Resolution Imaging Spectrometer (MERIS) from 2004 to 2009. Figure 6 shows MERIS chlorophyll images on 5 September 2004, 22 June 2005, 7 June 2006, 21 July 2007, 16 July 2008 and 29 July 2009. One can see three-fold structure of outstanding imagery features. (1) Offshore jets of high chlorophyll concentration water with the offshore lengths of O(200) km are shown in all images. The high chlorophyll concentration waters are originating from the Vietnam coast associated with summer upwelling (Kuo et al., 2000). (2) Wave-like patterns with the wavelengths of O(50) km are distributed along the southern fronts of offshore jets. (3) Vortex trains with the horizontal scale (diameter) of O(15–30) km and the spacing (wavelength) of O(50–80) km are distributed with wave-like patterns. Liu et al. (2015) measured that the off-shoreward propagation speed of spirals is 12 cm/s consistent with the velocity of the western boundary current. They suggested that the generation of vortices may be associated with strengthening of the velocity shear between the anticyclonic mesoscale eddies and the offshore jets.

We interpret the small-scale vortices shown on Fig. 6 as spiral trains according to their imagery pattern features and horizontal scales. The spirals are a type of submesoscale ocean processes, 10–25 km in size and characterized by the single polarity, cyclonic overwhelmingly (Munk et al., 2000; Zheng, 2018). Figure 7 shows a comparison of MERIS spiral imagery in Fig. 6l and spiral photograph off the northern coast of Africa in the Mediterranean Sea taken by space shuttle astronauts on 7 October 1984. One can see the high similarity between the two, implying that they represent the same physical process.

Yu et al. (2018) investigated submesoscale ocean vortex trains in the western SCS using MERIS chlorophyll concentration images, theoretical analysis and numerical modeling. They observed thirteen cases of vortex trains on the lee side of the Phú Quý Island in summer from 2005 to 2010. All the vortices are originating from the lee of Phú Quý Island and distributed on the offshore side of the offshore jets showing as high chlorophyll concentration patterns. The average diameter of the vortices is (28.1 ± 13.8) km and the average spacing is (66.3 ± 27.8) km. The vortex diameter tends to increase with increasing distance from the island. Figure 8 shows that the submesoscale cyclonic vortex trains can also be interpreted as spiral train, particularly in the case on 22 June 2005 (Fig. 8a). All the spiral trains are distributed along the shear zones of anticyclonic eddies, implying that eddies play an important role in propagation and growth of the spirals.

Fronts are called the lung of the ocean. This is because through the strong vertical motions in the frontal zone, fronts function like breath of the lung, i.e., transporting oxygen and CO2 from the atmosphere and materials in the surface water vertically downward to the deep layer, and nutrients in the deep layer water upward to the surface layer. Since fronts are formed by a combination of mechanisms, there are different types of fronts, such as estuarine fronts, shelf fronts, shelf-break fronts, coastal upwelling fronts and current fronts (Belkin et al., 2009; D’Asaro et al., 2011; Klemas, 2012). As a typical feature of marginal seas, fronts in the SCS are broadly distributed and have served as an important research hot spot since 2000 (Wang et al., 2001, 2013; Hu et al., 2003; Chang et al., 2006; Li et al., 2006; Liu et al., 2010b).

In recent years, the research of fronts in the SCS has taken important progresses. Using hydrographic survey and satellite data, Zhang et al. (2014a) observed three fronts in the southern Taiwan Strait in summer: the Taiwan Bank Front (TBF), the Southwest Coastal Upwelling Front (SCUF), and the Pearl River Plume Extension Front (PRPEF). The TBF is closely related to the Taiwan Bank upwelling, tidal mixing, and the Pearl River Plume Extension. The SCUF separates the wind-driven cold, saline coastal upwelling water from the warm, less saline offshore water. Owing to the frontal instability, SCUF exhibits both short temporal (several days) and small spatial (several km) scales, indicative of intense submesoscale processes. Meanwhile, a bifurcation phenomenon of the PRPEF was observed and attributed to the topography-following currents from the PRPEF.

Using the Belkin and O’Reilly algorithm and high-resolution (1 km) satellite SST and Chl a data from 2002 to 2011, Zeng et al. (2014) detected upwelling-induced fronts off the east/northeast coast of Hainan Island in the SCS. A three-dimensional ocean model forced by the Quick Scatterometer winds was used to study the three-dimensional structure of fronts and the relationship of the fronts to upwelling or summer monsoon. The results show that the frontal intensity (cross-frontal gradient) is strongly correlated with the along-shore winds, and has strong seasonal and weak inter-annual variations with a maximum of about 0.5°C/km at the subsurface (about 15 m) rather than that at the surface.

Jing et al. (2015) investigated upwelling-induced thermal fronts in the northwestern SCS using satellite data, two intensive mesoscale mapping surveys and three bottom-mounted ADCPs. The results indicate that pronounced surface cooling and upwelling-related fronts with a width of 20–50 km occur around Hainan Island and persist through the summer upwelling season. Jing et al. (2016) investigated seasonal thermal fronts associated with wind-driven coastal downwelling/upwelling in the northern SCS using satellite data and three repeated fine-resolution mapping surveys in winter, spring, and summer. The results show that vigorous thermal fronts develop over the broad shelf with variable widths and intensities in different seasons, which tend to be approximately aligned with the 20–100 m isobaths. The diagnostic analysis of potential vorticity suggests that the summer frontal activities induced by the coastal upwelling are more stable to convection and symmetric instabilities in comparison to the winter fronts associated with downwelling-favorable monsoon forcing.

Guo et al. (2017) found that strong fronts due to the Kuroshio intrusion and interactions with the SCS water are associated with intense upwelling, supplying nutrients from the subsurface SCS water and increasing phytoplankton productivity in the frontal zone. High chlorophyll concentration is more dynamically related to these fronts than to the alongshore wind, wind stress curl, and eddy kinetic energy on interannual time scale. Further examinations suggest that fronts associated with the Kuroshio intrusion are linked with large-scale climate variability. During El Niño years, the stronger Kuroshio intrusion results in stronger fronts that generate intensified local upwelling and enhanced Luzon winter blooms.

Ye et al. (2018) investigated the processes of occasional SST fronts and their impacts on chl-a concentration in the SCS, based on satellite and cruise observations from 2009 to 2013. The SST fronts were detected by an entropy-based edge detection algorithm method from satellite SST images with a 0.011° grid size. Three offshore SST fronts at the peripheries of eddies in the northern SCS were studied. The chl-a concentration as 6 times higher than that in the surrounding waters was found in the strong SST frontal zones. Using high-resolution SST reanalysis data, Shi et al. (2015) found pronounced seasonal variations of fronts in the coastal area of the northern SCS, which are accompanied by the seasonality of monsoons. The fronts cover a wider area of the coastal waters in winter than that in summer.

Existence of the vertical circulation is one of important features of continental shelf dynamics. However, it is hard to be determined due to difficulty to measure the vertical velocity of O(10–5) m/s directly. Xie et al. (2017) used the generalized omega equation to analyze the 3-D vertical circulation in the upwelling region and frontal zone east of Hainan Island, China using cruise observations of CTD, ADCP and TurboMAP (micro-scale shear probe) in July 2012 as shown in Fig. 9.

They found that distribution patterns of all the dynamic terms are featured by wave-like structures, i.e., alternative upwelling and downwelling zones with horizontal wavelength scale of O(20–40) km arranging from the coast to the deep waters as shown in Fig. 10. The maximum downward velocity reaches –8×10–5 m/s within the frontal zone along the 100 m isobath, accompanied by the maximum upward velocity of 8×10–5 m/s on its two sides.

Numerical models have been used for the research of submesoscale processes since early 2000 (Mahadevan and Tandon, 2006; Capet et al., 2008b, 2008c). For the SCS, Liu et al. (2010a) applied a primitive equation ocean model to simulate submesoscale activities and processes on the NSCS shelf. Their modeled temperature and density fields show that submesoscale activities are ubiquitous in the study area. The vertical velocity is considerably enhanced by submesoscale processes and reaches an average of 58 m/d in the subsurface. Meanwhile, the mixed layer depth is also deepened along the front, and the surface kinetic energy increases with intense vertical movement.

Zhong et al. (2017) used cruise data observed in the NSCS in 2014 and numerical modeling to analyze submesoscale vertical pump of an anticyclonic eddy. Their results confirm the fundamental role played by submesoscale ageostrophic dynamics in determining vertical transport in the upper water column not only in frontal regions or whenever submesoscale eddies are abundant, but also in mesoscale eddies. Meanwhile, submesoscale fronts in and around anticyclones are key contributors to the vertical velocity field and to vertical transport of the overall eddy structure without any detectable re-stratification

Dong and Zhong (2018) analyzed the spatiotemporal features of submesoscale processes in the northeastern SCS using high-resolution numerical simulation from 2009 to 2012. The results show that the submesoscale processes with a vertical relative vorticity that matches the local planetary vorticity are ubiquitous in the upper ocean of the northeastern SCS as shown in Fig. 11. Meanwhile, the submesoscale processes show the remarkable seasonal variation: strong and active in winter but weak and inactive in summer. The generation mechanism analysis reveals that strong flow straining and deep mixed layer in winter favor the submesoscale process generation via frontogenesis and mixed layer instability.

Li et al. (2019) also investigated spatial and seasonal variability of submesoscale current field, i.e., submesoscale turbulence, in the northeastern SCS using numerical simulation with a horizontal resolution of 1 km. The modeled results indicate that submesoscale currents are widespread in the surface mixed layer due to the mixed layer instabilities and frontogenesis. Submesoscale currents are more active in the northern than in the southern study area, since active eddies, especially cyclonic eddies, are mainly distributed in the north. In particular, submesoscale currents are highly intensified in the east of Dongsha Atoll and the south of Taiwan Island. The modeled results also show the seasonal variation of submesoscale currents, i.e., more active in winter than in summer.

Yang et al. (2019) estimated the submesoscale velocity field around the Xisha Islands in the SCS using a numerical model. The modeled results show very active submesoscale currents with associated kinetic energy as high as 0.2 m2/s2. They suggested that the kinetic energy results from the expense of mesoscale eddy decay.

We would like to cite the overview by McWilliams (2016) as concluding remark of this paper. He called submesoscale currents in the ocean “the recently discovered realm” and gave the following perspectives. “They are intermediate-scale flow structures in the form of density fronts and filaments, topographic wakes and persistent coherent vortices at the surface and throughout the interior. They are created from mesoscale eddies and strong currents, and they provide a dynamical conduit for energy transfer towards microscale dissipation and diapycnal mixing. Consideration is given to their generation mechanisms, instabilities, life cycles, disruption of approximately diagnostic force balance (e.g. geostrophic), turbulent cascades, internal-wave interactions, and transport and dispersion of materials. At a fundamental level, more questions remain than answers, implicating a program for further research.”

| [1] |

Alford M H. 2008. Observations of parametric subharmonic instability of the diurnal internal tide in the South China Sea. Geophysical Research Letters, 35(15): L15602. doi: 10.1029/2008GL034720

|

| [2] |

Bai Xiaolin, Li Xiaofeng, Lamb K G, et al. 2017. Internal solitary wave reflection near Dongsha Atoll, the South China Sea. Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans, 122(10): 7978–7991. doi: 10.1002/2017JC012880

|

| [3] |

Belkin I M, Cornillon P C, Sherman K. 2009. Fronts in large marine ecosystems. Progress in Oceanography, 81(1–4): 223–236

|

| [4] |

Buijsman M C, Kanarska Y, McWilliams J C. 2010. On the generation and evolution of nonlinear internal waves in the South China Sea. Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans, 115(C2): C02012

|

| [5] |

Callies J, Ferrari R. 2013. Interpreting energy and tracer spectra of upper-ocean turbulence in the submesoscale range (1–200 km). Journal of Physical Oceanography, 43(11): 2456–2474. doi: 10.1175/JPO-D-13-063.1

|

| [6] |

Callies J, Ferrari R, Klymak J M, et al. 2015. Seasonality in submesoscale turbulence. Nature Communications, 6: 6862. doi: 10.1038/ncomms7862

|

| [7] |

Cao Anzhou, Guo Zheng, Song Jinbao, et al. 2018. Near-inertial waves and their underlying mechanisms based on the South China Sea Internal Wave Experiment (2010–2011). Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans, 123(7): 5026–5040. doi: 10.1029/2018JC013753

|

| [8] |

Cao Xuefeng, Shi Hongyuan, Shi Maochong, et al. 2017. Model-simulated coastal trapped waves stimulated by typhoon in northwestern South China Sea. Journal of Ocean University of China, 16(6): 965–977. doi: 10.1007/s11802-017-3255-2

|

| [9] |

Capet X, McWilliams J C, Molemaker M J, et al. 2008a. Mesoscale to submesoscale transition in the California Current system. Part I: flow structure, eddy flux, and observational tests. Journal of Physical Oceanography, 38(1): 29–43

|

| [10] |

Capet X, Campos E J, Paiva A M. 2008b. Submesoscale activity over the Argentinian shelf. Geophysical Research Letter, 35(15): L15605. doi: 10.1029/2008GL034736

|

| [11] |

Capet X, McWilliams J C, Molemaker M J, et al. 2008c. Mesoscale to submesoscale transition in the California current system. Part III: energy balance and flux. Journal of Physical Oceanography, 38(10): 2256–2269

|

| [12] |

Chang Yi, Shimada T, Lee M A, et al. 2006. Wintertime sea surface temperature fronts in the Taiwan Strait. Geophysical Research Letter, 33(23): L23603. doi: 10.1029/2006GL027415

|

| [13] |

Chen Shengli, Hu Jianyu, Polton J A. 2015. Features of near-inertial motions observed on the northern South China Sea shelf during the passage of two typhoons. Acta Oceanologica Sinica, 34(1): 38–43. doi: 10.1007/s13131-015-0594-y

|

| [14] |

Chen Gengxin, Xue Huijie, Wang Dongxiao, et al. 2013. Observed near-inertial kinetic energy in the northwestern South China Sea. Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans, 118(10): 4965–4977. doi: 10.1002/jgrc.20371

|

| [15] |

Chen Liang, Zheng Quanan, Xiong Xuejun, et al. 2018. A new type of internal solitary waves with a re-appearance period of 23 h observed in the South China Sea. Acta Oceanologica Sinica, 37(9): 116–118. doi: 10.1007/s13131-018-1252-y

|

| [16] |

D’Asaro E A. 1988. Generation of submesoscale vortices: a new mechanism. Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans, 93(C6): 6685–6693. doi: 10.1029/JC093iC06p06685

|

| [17] |

D’Asaro E A, Lee C, Rainville L, et al. 2011. Enhanced turbulence and energy dissipation at ocean fronts. Science, 332(6027): 318–322. doi: 10.1126/science.1201515

|

| [18] |

Dong Di, Yang Xiaofeng, Li Xiaofeng, et al. 2016. SAR observation of eddy-induced mode-2 internal solitary waves in the South China Sea. IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing, 54(11): 6674–6686. doi: 10.1109/TGRS.2016.2587752

|

| [19] |

Dong Jihai, Zhong Yisen. 2018. The spatiotemporal features of submesoscale processes in the northeastern South China Sea. Acta Oceanologica Sinica, 37(11): 8–18. doi: 10.1007/s13131-018-1277-2

|

| [20] |

Farmer D M, Alford M H, Lien R C, et al. 2011. From Luzon strait to Dongsha Plateau: Stages in the life of an internal wave. Oceanography, 24(4): 64–77. doi: 10.5670/oceanog.2011.95

|

| [21] |

Ferrari R, Wunsch C. 2009. Ocean circulation kinetic energy: Reservoirs, sources, and sinks. Annual Review of Fluid Mechanism, 41: 253–282. doi: 10.1146/annurev.fluid.40.111406.102139

|

| [22] |

Guan Shoude, Zhao Wei, Huthnance J, et al. 2014. Observed upper ocean response to typhoon Megi (2010) in the Northern South China Sea. Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans, 119(5): 3134–3157. doi: 10.1002/2013JC009661

|

| [23] |

Gula J, Molemaker M J, McWilliams J C. 2016. Topographic generation of submesoscale centrifugal instability and energy dissipation. Nature Communication, 7: 12811. doi: 10.1038/ncomms12811

|

| [24] |

Guo Lin, Xiu Peng, Chai Fei, et al. 2017. Enhanced chlorophyll concentrations induced by Kuroshio intrusion fronts in the northern South China Sea. Geophysical Research Letters, 44(22): 11565–11572. doi: 10.1002/2017GL075336

|

| [25] |

He Qingyou, Zhan Haigang, Cai Shuqun, et al. 2018. A new assessment of mesoscale eddies in the South China Sea: Surface features, three-dimensional structures, and thermohaline transports. Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans, 123(7): 4906–4929. doi: 10.1029/2018JC014054

|

| [26] |

Helfrich K R, Grimshaw R H J. 2008. Nonlinear disintegration of the internal tide. Journal of Physical Oceanography, 38(3): 686–701. doi: 10.1175/2007JPO3826.1

|

| [27] |

Ho C R, Kuo N J, Zheng Quanan, et al. 2000. Dynamically active areas in the South China Sea detected from TOPEX/POSEIDON satellite altimeter data. Remote Sensing of Environment, 71(3): 320–328. doi: 10.1016/S0034-4257(99)00094-2

|

| [28] |

Hu Jianyu, Ho C R, Xie Lingling, et al. 2019. Regional Oceanography of the South China Sea. Singapore: World Scientific, https://doi.org/10.1142/11461

|

| [29] |

Hu Jianyu, Kawamura H, Hong Huasheng, et al. 2000. A review on the currents in the South China Sea: Seasonal circulation, South China Sea Warm Current and Kuroshio Intrusion. Journal of Oceanography, 56(6): 607–624. doi: 10.1023/A:1011117531252

|

| [30] |

Hu Jianyu, Kawamura H, Hong Huasheng, et al. 2001. 3≈6 months variation of sea surface height in the South China Sea and its adjacent ocean. Journal of Oceanography, 57(1): 69–78. doi: 10.1023/A:1011126804461

|

| [31] |

Hu Jianyu, Kawamura H, Tang Danling. 2003. Tidal front around the Hainan Island, northwest of the South China Sea. Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans, 108(C11): 3342. doi: 10.1029/2003JC001883

|

| [32] |

Huang Xiaodong, Zhao Wei, Tian Jiwei, et al. 2014. Mooring observations of internal solitary waves in the deep basin west of Luzon Strait. Acta Oceanologica Sinica, 33(3): 82–89. doi: 10.1007/s13131-014-0416-7

|

| [33] |

Jing Zhiyou, Qi Yiquan, Du Yan, et al. 2015. Summer upwelling and thermal fronts in the northwestern South China Sea: Observational analysis of two mesoscale mapping surveys. Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans, 120(3): 1993–2006. doi: 10.1002/2014JC010601

|

| [34] |

Jing Zhiyou, Qi Yiquan, Fox-Kemper B, et al. 2016. Seasonal thermal fronts on the northern South China Sea shelf: Satellite measurements and three repeated field surveys. Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans, 121(3): 1914–1930. doi: 10.1002/2015JC011222

|

| [35] |

Klemas V. 2012. Remote sensing of coastal plumes and ocean fronts: Overview and case study. Journal of Coastal Research, 28(1A): 1–7

|

| [36] |

Kuo N J, Zheng Quanan, Ho C R. 2000. Satellite observation of upwelling along the western coast of the South China Sea. Remote Sensing of Environment, 74(3): 463–470. doi: 10.1016/S0034-4257(00)00138-3

|

| [37] |

Lapeyre G, Klein P. 2006. Dynamics of the upper oceanic layers in terms of surface quasigeostrophy theory. Journal of Physical Oceanography, 36(2): 165–176. doi: 10.1175/JPO2840.1

|

| [38] |

Lévy M, Ferrari R, Franks P J S, et al. 2012. Bringing physics to life at the submesoscale. Geophysical Research Letters, 39(14): L14602

|

| [39] |

Lévy M, Franks P J S, Smith K S. 2018. The role of submesoscale currents in structuring marine ecosystems. Nature Communication, 9: 4758. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-07059-3

|

| [40] |

Lévy M, Klein P, Treguier A M. 2001. Impact of sub-mesoscale physics on production and subduction of phytoplankton in an oligotrophic regime. Journal of Marine Research, 59(4): 535–565. doi: 10.1357/002224001762842181

|

| [41] |

Li Jianing, Dong Jihai, Yang Qingxuan, et al. 2018. Spatial-temporal variability of submesoscale currents in the South China Sea. Journal of Oceanology and Limnology, 37(2): 474–485

|

| [42] |

Li Qiang, Farmer D M. 2011. The generation and evolution of nonlinear internal waves in the deep basin of the South China Sea. Journal of Physical Oceanography, 41(7): 1345–1363. doi: 10.1175/2011JPO4587.1

|

| [43] |

Li Chunyan, Hu Jianyu, Jan S, et al. 2006. Winter-spring fronts in Taiwan Strait. Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans, 111(C11): C11S13

|

| [44] |

Li Xiaofeng, Jackson C R, Pichel W G. 2013. Internal solitary wave refraction at Dongsha Atoll, South China Sea. Geophysical Research Letters, 40(12): 3128–3132. doi: 10.1002/grl.50614

|

| [45] |

Li Jiaxuan, Zhang Ren, Jin Baogang. 2011. Eddy characteristics in the Northern South China Sea as inferred from Lagrangian drifter data. Ocean Science, 7(5): 661–669. doi: 10.5194/os-7-661-2011

|

| [46] |

Li Junyi, Zheng Quanan, Hu Jianyu, et al. 2015. Wavelet analysis of coastal-trapped waves along the China coast generated by winter storms in 2008. Acta Oceanologica Sinica, 34(11): 22–31. doi: 10.1007/s13131-015-0701-0

|

| [47] |

Li Junyi, Zheng Quanan, Hu Jianyu, et al. 2016. A case study of winter storm-induced continental shelf waves in the northern South China Sea in winter 2009. Continental Shelf Research, 125: 127–135. doi: 10.1016/j.csr.2016.06.013

|

| [48] |

Li Jianning, Dong Jihai, Yang Qingxuan, et al. 2019. Spatial-temporal variability of submesoscale currents in the South China Sea. Journal of Oceanoglogy and Limnonlogy, 37(2): 474–485. doi: 10.1007/s00343-019-8077-1

|

| [49] |

Liang Xinfeng, Zhang Xiaoqian, Tian Jiwei. 2005. Observation of internal tides and near-inertial motions in the upper 450 m layer of the northern South China Sea. Chinese Science Bulletin, 50(24): 2890–2895

|

| [50] |

Lien R C, Tang T Y, Chang M H, et al. 2005. Energy of nonlinear internal waves in the South China Sea. Geophysical Research Letters, 32(5): L05615

|

| [51] |

Liu Guangpeng, Bracco A, Passow U. 2018a. The influence of mesoscale and submesoscale circulation on sinking particles in the northern Gulf of Mexico. Elementa Science of the Anthropocene, 6(1): 36

|

| [52] |

Liu Sumei, Guo Xinyu, Chen Qi, et al. 2010b. Nutrient dynamics in the winter thermohaline frontal zone of the northern shelf region of the South China Sea. Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans, 115(C11): C11020. doi: 10.1029/2009JC005951

|

| [53] |

Liu Junliang, He Yinghui, Li Juan, et al. 2018b. Cases study of nonlinear interaction between near-inertial waves induced by typhoon and diurnal tides near the Xisha Islands. Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans, 123(4): 2768–2784. doi: 10.1029/2017JC013555

|

| [54] |

Liu Guoqiang, He Yijun, Shen Hui, et al. 2010a. Submesoscale activity over the shelf of the northern South China Sea in summer: simulation with an embedded model. Chinese Journal of Oceanology and Limnology, 28(5): 1073–1079. doi: 10.1007/s00343-010-0030-2

|

| [55] |

Liu Fenfen, Tang Shilin, Chen Chuqun. 2015. Satellite observations of the small-scale cyclonic eddies in the western South China Sea. Biogeosciences, 12(2): 299–305. doi: 10.5194/bg-12-299-2015

|

| [56] |

Mahadevan A, Archer D. 2000. Modeling the impact of fronts and mesoscale circulation on the nutrient supply and biogeochemistry of the upper ocean. Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans, 105(C1): 1209–1225. doi: 10.1029/1999JC900216

|

| [57] |

Mahadevan A, Tandon A. 2006. An analysis of mechanisms for submesoscale vertical motion at ocean fronts. Ocean Modelling, 14(3–4): 241–256

|

| [58] |

McWilliams J C. 1985. Submesoscale, coherent vortices in the ocean. Reviews of Geophysics, 23(2): 165–182. doi: 10.1029/RG023i002p00165

|

| [59] |

McWilliams J C. 2016. Submesoscale currents in the ocean. Proceedings of the Royal Society A: Mathematical, Physical and Engineering Sciences, 472(2189): 20160117. doi: 10.1098/rspa.2016.0117

|

| [60] |

McWilliams J C. 2017. Submesoscale surface fronts and filaments: Secondary circulation, buoyancy flux, and frontogenesis. Journal of Fluid Mechanics, 823: 391–432. doi: 10.1017/jfm.2017.294

|

| [61] |

Mensa J A, Garraffo Z, Griffa A, et al. 2013. Seasonality of the submesoscale dynamics in the Gulf Stream region. Ocean Dynamic, 63(8): 923–941. doi: 10.1007/s10236-013-0633-1

|

| [62] |

Munk W, Armi L, Fischer K, et al. 2000. Spirals on the sea. Proceedings of the Royal Society A: Mathematical, Physical and Engineering Sciences, 456(1997): 1217–1280. doi: 10.1098/rspa.2000.0560

|

| [63] |

Nan Feng, He Zhigang, Zhou Hui, et al. 2011. Three long-lived anticyclonic eddies in the northern South China Sea. Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans, 116(C5): C05002

|

| [64] |

Qiu Bo, Chen Shuiming, Sasaki H, et al. 2014. Seasonal mesoscale and submesoscale eddy variability along the North Pacific Subtropical Countercurrent. Journal of Physical Oceanography, 44(12): 3079–3098. doi: 10.1175/JPO-D-14-0071.1

|

| [65] |

Qiu Bo, Nakano T, Chen Shuiming, et al. 2017. Submesoscale transition from geostrophic flows to internal waves in the northwestern Pacific upper ocean. Nature Communications, 8: 14055. doi: 10.1038/ncomms14055

|

| [66] |

Qu Tangdong, Kim Y Y, Yaremchuk M, et al. 2004. Can Luzon Strait transport play a role in conveying the impact of ENSO to the South China Sea?. Journal of Climate, 17(18): 3644–3657. doi: 10.1175/1520-0442(2004)017<3644:CLSTPA>2.0.CO;2

|

| [67] |

Ramp S R, Tang T Y, Duda T F, et al. 2004. Internal solitons in the northeastern South China Sea part I: sources and deep water propagation. IEEE Journal of Oceanic Engineering, 29(4): 1157–1181. doi: 10.1109/JOE.2004.840839

|

| [68] |

Ramp S R, Yang Y J, Bahr F L. 2010. Characterizing the nonlinear internal wave climate in the northeastern South China Sea. Nonlinear Processes in Geophysics, 17(5): 481–498. doi: 10.5194/npg-17-481-2010

|

| [69] |

Renault L, McWilliams J C, Gula J. 2018. Dampening of submesoscale currents by air-sea stress coupling in the Californian upwelling system. Scientific Reports, 8: 13388. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-31602-3

|

| [70] |

Sasaki H, Klein P, Sasai Y, et al. 2017. Regionality and seasonality of submesoscale and mesoscale turbulence in the North Pacific Ocean. Ocean Dynamics, 67(9): 1195–1216. doi: 10.1007/s10236-017-1083-y

|

| [71] |

Shi Rui, Guo Xinyu, Wang Dongxiao, et al. 2015. Seasonal variability in coastal fronts and its influence on sea surface wind in the Northern South China Sea. Deep Sea Research Part II: Topical Studies in Oceanography, 119: 30–39. doi: 10.1016/j.dsr2.2013.12.018

|

| [72] |

Shu Yeqiang, Pan Jiayi, Wang Dongxiao, et al. 2016. Generation of near-inertial oscillations by summer monsoon onset over the South China Sea in 1998 and 1999. Deep Sea Research Part I: Oceanographic Research Papers, 118: 10–19. doi: 10.1016/j.dsr.2016.10.008

|

| [73] |

Sun Zhenyu, Hu Jianyu, Zheng Quanan, et al. 2011b. Strong near-inertial oscillations in geostrophic shear in the northern South China Sea. Journal of Oceanography, 67(4): 377–384. doi: 10.1007/s10872-011-0038-z

|

| [74] |

Sun Lu, Zheng Quanan, Wang Dongxiao, et al. 2011a. A case study of near-inertial oscillation in the South China Sea using mooring observations and satellite altimeter data. Journal of Oceanography, 67(6): 677–687. doi: 10.1007/s10872-011-0081-9

|

| [75] |

Taylor J R, Bachman S, Stamper M, et al. 2018. Submesoscale Rossby waves on the Antarctic circumpolar current. Science Advance, 4(3): eaao2824

|

| [76] |

Wang Juan, Huang Weigen, Yang Jingsong, et al. 2013. Study of the propagation direction of the internal waves in the South China Sea using satellite images. Acta Oceanologica Sinica, 32(5): 42–50. doi: 10.1007/s13131-013-0312-6

|

| [77] |

Wang Guihua, Li Jiaxun, Wang Chunzai, et al. 2012. Interactions among the winter monsoon, ocean eddy and ocean thermal front in the South China Sea. Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans, 117(C8): C08002

|

| [78] |

Wang Dongxiao, Liu Yun, Qi Yiquan, et al. 2001. Seasonal variability of thermal fronts in the northern South China Sea from satellite data. Geophysical Research Letters, 28(20): 3963–3966. doi: 10.1029/2001GL013306

|

| [79] |

Wang Guihua, Su Jilan, Chu P C. 2003. Mesoscale eddies in the South China Sea observed with altimeter data. Geophysical Research Letters, 30(21): 2121. doi: 10.1029/2003GL018532

|

| [80] |

Xiao Jingen, Xie Qiang, Wang Dongxiao, et al. 2016. On the near-inertial variations of meridional overturning circulation in the South China Sea. Ocean Science, 12(1): 335–344. doi: 10.5194/os-12-335-2016

|

| [81] |

Xie Lingling, Pallàs-Sanz E, Zheng Quanan, et al. 2017. Diagnosis of 3D vertical circulation in the upwelling and frontal zones east of Hainan Island, China. Journal of Physical Oceanography, 47(4): 755–774. doi: 10.1175/JPO-D-16-0192.1

|

| [82] |

Xie Xiaohui, Shang Xiaodong, van Haren H, et al. 2011. Observations of parametric subharmonic instability-induced near-inertial waves equatorward of the critical diurnal latitude. Geophysical Research Letters, 38(5): L05603

|

| [83] |

Xie Lingling, Zheng Quanan. 2017. New insight into the South China Sea: Rossby normal modes. Acta Oceanologica Sinica, 36(7): 1–3. doi: 10.1007/s13131-017-1077-0

|

| [84] |

Xie Lingling, Zheng Quanan, Tian Jiwei, et al. 2016. Cruise Observation of Rossby waves with finite wavelengths propagating from the Pacific to the South China Sea. Journal of Physical Oceanography, 46(10): 2897–2913. doi: 10.1175/JPO-D-16-0071.1

|

| [85] |

Xie Lingling, Zheng Quanan, Zhang Shuwen, et al. 2018. The Rossby normal modes in the South China Sea deep basin evidenced by satellite altimetry. International Journal of Remote Sensing, 39(2): 399–417. doi: 10.1080/01431161.2017.1384591

|

| [86] |

Xu Zhenhua, Yin Baoshu, Hou Yijun, et al. 2013. Variability of internal tides and near-inertial waves on the continental slope of the northwestern South China Sea. Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans, 118(1): 197–211. doi: 10.1029/2012JC008212

|

| [87] |

Yang Bing, Hou Yijun. 2014. Near-inertial waves in the wake of 2011 Typhoon Nesat in the northern South China Sea. Acta Oceanologica Sinica, 33(11): 102–111. doi: 10.1007/s13131-014-0559-6

|

| [88] |

Yang Qingxuan, Nikurashin M, Sasaki H, et al. 2019. Dissipation of mesoscale eddies and its contribution to mixing in the northern South China Sea. Scientific Reports, 9: 556. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-36610-x

|

| [89] |

Ye Haijun, Kalhoro M A, Morozov E, et al. 2018. Increased chlorophyll-a concentration in the South China Sea caused by occasional sea surface temperature fronts at peripheries of eddies. International Journal of Remote Sensing, 39(13): 4360–4375. doi: 10.1080/01431161.2017.1399479

|

| [90] |

Yu Jie, Zheng Quanan, Jing Zhiyou, et al. 2018. Satellite observations of sub-mesoscale vortex trains in the western boundary of the South China Sea. Journal of Marine Systems, 183: 56–62. doi: 10.1016/j.jmarsys.2018.03.010

|

| [91] |

Zeng Xuezhi, Belkin I M, Peng Shiqiu, et al. 2014. East Hainan upwelling fronts detected by remote sensing and modelled in summer. International Journal of Remote Sensing, 35(11–12): 4441–4451

|

| [92] |

Zhang Z, Fringer O B, Ramp S R. 2011. Three-dimensional, nonhydrostatic numerical simulation of nonlinear internal wave generation and propagation in the South China Sea. Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans, 116(C5): C05022

|

| [93] |

Zhang Fan, Li Xiaofeng, Hu Jianyu, et al. 2014a. Summertime sea surface temperature and salinity fronts in the southern Taiwan Strait. International Journal of Remote Sensing, 35(11–12): 4452–4466

|

| [94] |

Zhang Zhengguang, Qiu Bo, Klein P, et al. 2019. The influence of geostrophic strain on oceanic ageostrophic motion and surface chlorophyll. Nature Communications, 10: 2838. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-10883-w

|

| [95] |

Zhang Shuwen, Xie Lingling, Zhao Hui, et al. 2014b. Tropical storm-forced near-inertial energy dissipation in the southeast continental shelf region of Hainan Island. Science in China: Earth Science, 57(8): 1879–1884. doi: 10.1007/s11430-013-4813-0

|

| [96] |

Zhao Zhongxiang. 2014. Internal tide radiation from the Luzon Strait. Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans, 119(8): 5434–5448. doi: 10.1002/2014JC010014

|

| [97] |

Zhao Zhongxiang, Klemas V, Zheng Quanan, et al. 2004. Remote sensing evidence for baroclinic tide origin of internal solitary waves in the northeastern South China Sea. Geophysical Research Letter, 31(6): L06032

|

| [98] |

Zhao Zhongxiang, Liu Bingqing, Li Xiaofeng. 2014. Internal solitary waves in the China seas observed using satellite remote-sensing techniques: A review and perspectives. International Journal of Remote Sensing, 35(11–12): 3926–3946

|

| [99] |

Zhao Ruixiang, Zhu Xiaohua, Park J H, et al. 2018. Internal tides in the northwestern South China Sea observed by pressure-recording inverted echo sounders. Progress in Oceanography, 168: 112–122. doi: 10.1016/j.pocean.2018.09.019

|

| [100] |

Zheng Quanan. 2017. Satellite SAR Detection of Sub-Mesoscale Ocean Dynamic Processes. London: World Scientific, 121–178

|

| [101] |

Zheng Quanan. 2018. Satellite SAR Detection of Sub-mesoscale Ocean Dynamic Processes (in Chinese). Xie Lingling, Ye Xiaomin, trans. Beijing: China Ocean Press, 1–215

|

| [102] |

Zheng Quanan, Fang Guohong, Song Y T. 2006. Introduction to special section: Dynamics and Circulation of the Yellow, East, and South China Seas. Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans, 111(C11): C11S01

|

| [103] |

Zheng Quanan, Ho C R, Xie Lingling, et al. 2019. A case study of a Kuroshio main path cut-off event and impacts on the South China Sea in fall-winter 2013–2014. Acta Oceanologica Sinica, 38(4): 12–19. doi: 10.1007/s13131-019-1411-9

|

| [104] |

Zheng Quanan, Hu Jianyu, Zhu Benlu, et al. 2014. Standing wave modes observed in the South China Sea deep basin. Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans, 119(7): 4185–4199. doi: 10.1002/2014JC009957

|

| [105] |

Zheng Quanan, Lin Hui, Meng Junmin, et al. 2008. Sub-mesoscale ocean vortex trains in the Luzon Strait. Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans, 113(C4): C04032

|

| [106] |

Zheng Quanan, Susanto R D, Ho C R, et al. 2007. Statistical and dynamical analyses of generation mechanisms of solitary internal waves in the northern South China Sea. Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans, 112(C3): C03021

|

| [107] |

Zheng Quanan, Tai C K, Hu Jianyu, et al. 2011. Satellite altimeter observations of nonlinear Rossby eddy–Kuroshio interaction at the Luzon Strait. Journal of Oceanography, 67(4): 365–376. doi: 10.1007/s10872-011-0035-2

|

| [108] |

Zheng Quanan, Xie Lingling, Zheng Zhewen, et al. 2017. Progress in research of mesoscale eddies in the South China Sea. Advances in Marine Sciences (in Chinese), 35(2): 131–158

|

| [109] |

Zhong Yisen, Bracco A. 2013. Submesoscale impacts on horizontal and vertical transport in the Gulf of Mexico. Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans, 118(10): 5651–5668. doi: 10.1002/jgrc.20402

|

| [110] |

Zhong Yisen, Bracco A, Tian Jiwei, et al. 2017. Observed and simulated submesoscale vertical pump of an anticyclonic eddy in the South China Sea. Scientific Reports, 7: 44011. doi: 10.1038/srep44011

|

| [111] |

Zhu Dayong, Li Li. 2007. Near inertial oscillations in shelf-break of northern South China Sea after passage of typhoon Wayne. Journal of Tropical Oceanography (in Chinese), 26(4): 1–7

|

| [112] |

Zhuang Wei, Du Yan, Wang Dongxiao, et al. 2010. Pathways of mesoscale variability in the South China Sea. Chinese Journal of Oceanologia and Limnologia, 28(5): 1055–1067. doi: 10.1007/s00343-010-0035-x

|

| 1. | Qi Feng, Hao Shen, Guohao Zhu, et al. Chlorophyll bloom triggered by tropical storm chedza at the southern tip of madagascar island. Environmental Research Communications, 2024, 6(1): 011001. doi:10.1088/2515-7620/ad1842 | |

| 2. | Jinchao He, Yongsheng Xu, Hanwei Sun, et al. Sea Surface Height Wavenumber Spectrum from Airborne Interferometric Radar Altimeter. Remote Sensing, 2024, 16(8): 1359. doi:10.3390/rs16081359 | |

| 3. | Zhiwei Zhang. Submesoscale Dynamic Processes in the South China Sea. Ocean-Land-Atmosphere Research, 2024, 3 doi:10.34133/olar.0045 | |

| 4. | Qian Liu, Jian Cui, Huan Mei, et al. Study on the Load Characteristics of Submerged Body Under Internal Solitary Waves on the Continental Shelf and Slope. China Ocean Engineering, 2024, 38(5): 809. doi:10.1007/s13344-024-0063-5 | |

| 5. | Yuxia Jia, Yankun Gong, Zheen Zhang, et al. Three-dimensional numerical simulations of oblique internal solitary wave-wave interactions in the South China Sea. Frontiers in Marine Science, 2024, 10 doi:10.3389/fmars.2023.1292078 | |

| 6. | Rui Wang, Xiaoqi Ding, Hao Shen, et al. Phytoplankton Blooms with Sequential Cyclonic and Anticyclonic Eddies During the Passage of Tropical Cyclone Hibaru. Tellus A: Dynamic Meteorology and Oceanography, 2024, 76(1): 1. doi:10.16993/tellusa.3241 | |

| 7. | Liang Chen, Xuejun Xiong, Quanan Zheng, et al. Analysis of mooring-observed bottom current on the northern continental shelf of the South China Sea. Frontiers in Marine Science, 2023, 10 doi:10.3389/fmars.2023.1164790 | |

| 8. | Tianhao Wang, Yu Sun, Hua Su, et al. Declined trends of chlorophyll a in the South China Sea over 2005–2019 from remote sensing reconstruction. Acta Oceanologica Sinica, 2023, 42(1): 12. doi:10.1007/s13131-022-2097-y | |

| 9. | Guangbing Yang, Quanan Zheng, Xuejun Xiong. Subthermocline eddies carrying the Indonesian Throughflow water observed in the southeastern tropical Indian Ocean. Acta Oceanologica Sinica, 2023, 42(5): 1. doi:10.1007/s13131-022-2085-2 | |

| 10. | Fei Gao, Ping Hu, Fanghua Xu, et al. Effects of Internal Waves on Acoustic Temporal Coherence in the South China Sea. Journal of Marine Science and Engineering, 2023, 11(2): 374. doi:10.3390/jmse11020374 | |

| 11. | Caijing Huang, Lili Zeng, Dongxiao Wang, et al. Submesoscale eddies in eastern Guangdong identified using high-frequency radar observations. Deep Sea Research Part II: Topical Studies in Oceanography, 2023, 207: 105220. doi:10.1016/j.dsr2.2022.105220 | |

| 12. | K. Tan, L. Xie, P. Bai, et al. Modulation Effects of Mesoscale Eddies on Sea Surface Wave Fields in the South China Sea Derived From a Wave Spectrometer Onboard the China‐France Ocean Satellite. Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans, 2023, 128(1) doi:10.1029/2021JC018088 | |

| 13. | Chunhua Qiu, Benjun He, Dongxiao Wang, et al. Mechanisms of a shelf submesoscale front in the northern South China Sea. Deep Sea Research Part I: Oceanographic Research Papers, 2023, 202: 104197. doi:10.1016/j.dsr.2023.104197 | |

| 14. | Haibo Tang, Yeqiang Shu, Dongxiao Wang, et al. Submesoscale processes observed by high-frequency float in the western South China sea. Deep Sea Research Part I: Oceanographic Research Papers, 2023, 192: 103896. doi:10.1016/j.dsr.2022.103896 | |

| 15. | Hao Pan, Chunhua Qiu, Hong Liang, et al. Different vertical heat transport induced by submesoscale motions in the shelf and open sea of the northwestern South China Sea. Frontiers in Marine Science, 2023, 10 doi:10.3389/fmars.2023.1236864 | |

| 16. | Xuekun Shang, Yeqiang Shu, Dongxiao Wang, et al. Submesoscale Motions Driven by Down‐Front Wind Around an Anticyclonic Eddy With a Cold Core. Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans, 2023, 128(8) doi:10.1029/2022JC019173 | |

| 17. | Hong Long Bui, Minh Thu Phan. Upwelling phenomenon in the marine regions of Southern Central of Vietnam: a review. Vietnam Journal of Marine Science and Technology, 2022, 22(2): 103. doi:10.15625/1859-3097/17231 | |

| 18. | Lei Yang, Lina Lin, Long Fan, et al. Satellite Altimetry: Achievements and Future Trends by a Scientometrics Analysis. Remote Sensing, 2022, 14(14): 3332. doi:10.3390/rs14143332 | |

| 19. | Luis Felipe Navarro-Olache, Rafael Hernandez-Walls, Ruben Castro, et al. Evidence of submesoscale coastal eddies inside Todos Santos Bay, Baja California, México. Ocean and Coastal Research, 2022, 70(suppl 1) doi:10.1590/2675-2824070.22020lfno | |

| 20. | Ruixi Zheng, Zhiyou Jing. Submesoscale-enhanced filaments and frontogenetic mechanism within mesoscale eddies of the South China Sea. Acta Oceanologica Sinica, 2022, 41(7): 42. doi:10.1007/s13131-021-1971-3 | |

| 21. | Yinchao Chen, Qian P. Li, Jiancheng Yu. Submesoscale variability of subsurface chlorophyll-a across eddy-driven fronts by glider observations. Progress in Oceanography, 2022, 209: 102905. doi:10.1016/j.pocean.2022.102905 | |

| 22. | Huarong Xie, Qing Xu, Quanan Zheng, et al. Assessment of theoretical approaches to derivation of internal solitary wave parameters from multi-satellite images near the Dongsha Atoll of the South China Sea. Acta Oceanologica Sinica, 2022, 41(6): 137. doi:10.1007/s13131-022-2015-3 | |

| 23. | Haijin Cao, Xin Meng, Zhiyou Jing, et al. High-resolution simulation of upper-ocean submesoscale variability in the South China Sea: Spatial and seasonal dynamical regimes. Acta Oceanologica Sinica, 2022, 41(7): 26. doi:10.1007/s13131-022-2014-4 | |

| 24. | Lei Zhang, Jihai Dong. Dynamic Characteristics of a Submesoscale Front and Associated Heat Fluxes Over the Northeastern South China Sea Shelf. Atmosphere-Ocean, 2021, 59(3): 190. doi:10.1080/07055900.2021.1958741 | |

| 25. | Jieshuo Xie, Wendong Fang, Yinghui He, et al. Variation of Internal Solitary Wave Propagation Induced by the Typical Oceanic Circulation Patterns in the Northern South China Sea Deep Basin. Geophysical Research Letters, 2021, 48(15) doi:10.1029/2021GL093969 | |

| 26. | Lingling Xie, Yi Guan, Jianyu Hu, et al. Advances in interscale and interdisciplinary approaches to the South China Sea. Acta Oceanologica Sinica, 2021, 40(11): 196. doi:10.1007/s13131-021-1963-3 | |

| 27. | Boris Galperin, Semion Sukoriansky, Bo Qiu. Seasonal oceanic variability on meso- and submesoscales: a turbulence perspective. Ocean Dynamics, 2021, 71(4): 475. doi:10.1007/s10236-021-01444-1 | |

| 28. | Junyi Li, Huiyuan Zheng, Lingling Xie, et al. Response of Total Suspended Sediment and Chlorophyll-a Concentration to Late Autumn Typhoon Events in the Northwestern South China Sea. Remote Sensing, 2021, 13(15): 2863. doi:10.3390/rs13152863 | |

| 29. | Shijian Hu, Lingling Liu, Cong Guan, et al. Dynamic features of near-inertial oscillations in the Northwestern Pacific derived from mooring observations from 2015 to 2018. Journal of Oceanology and Limnology, 2020, 38(4): 1092. doi:10.1007/s00343-020-9332-1 | |

| 30. | Xiaolong Huang, Zhiyou Jing, Ruixi Zheng, et al. Dynamical analysis of submesoscale fronts associated with wind-forced offshore jet in the western South China Sea. Acta Oceanologica Sinica, 2020, 39(11): 1. doi:10.1007/s13131-020-1671-4 | |

| 31. | Junqiang Shen, Wendong Fang, Shanwu Zhang, et al. Observed Internal Tides and Near‐Inertial Waves in the Northern South China Sea: Intensified f‐Band Energy Induced by Parametric Subharmonic Instability. Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans, 2020, 125(10) doi:10.1029/2020JC016324 | |

| 32. | Guang-Bing Yang, Lian-Gang Lü, Zhan-Peng Zhuang, et al. Cruise observation of shallow water response to typhoon Damrey 2012 in the Yellow Sea. Continental Shelf Research, 2017, 148: 1. doi:10.1016/j.csr.2017.09.006 | |

| 33. | Bing Yang, Yijun Hou, Po Hu. Observed near-inertial waves in the wake of Typhoon Hagupit in the northern South China Sea. Chinese Journal of Oceanology and Limnology, 2015, 33(5): 1265. doi:10.1007/s00343-015-4254-z | |

| 34. | Shengli Chen, Jianyu Hu, Jeff A. Polton. Features of near-inertial motions observed on the northern South China Sea shelf during the passage of two typhoons. Acta Oceanologica Sinica, 2015, 34(1): 38. doi:10.1007/s13131-015-0594-y | |

| 35. | Zhenyu Sun, Jianyu Hu, Quanan Zheng, et al. Comparison of typhoon-induced near-inertial oscillations in shear flow in the northern South China Sea. Acta Oceanologica Sinica, 2015, 34(11): 38. doi:10.1007/s13131-015-0746-0 | |

| 36. | Shuwen Zhang, Lingling Xie, Yijun Hou, et al. Tropical storm-induced turbulent mixing and chlorophyll-a enhancement in the continental shelf southeast of Hainan Island. Journal of Marine Systems, 2014, 129: 405. doi:10.1016/j.jmarsys.2013.09.002 | |

| 37. | Bing Yang, Yijun Hou. Near-inertial waves in the wake of 2011 Typhoon Nesat in the northern South China Sea. Acta Oceanologica Sinica, 2014, 33(11): 102. doi:10.1007/s13131-014-0559-6 | |

| 38. | Gengxin Chen, Huijie Xue, Dongxiao Wang, et al. Observed near-inertial kinetic energy in the northwestern South China Sea. Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans, 2013, 118(10): 4965. doi:10.1002/jgrc.20371 | |

| 39. | Lu Sun, Quan’an Zheng, Tswen-Yung Tang, et al. Upper ocean near-inertial response to 1998 Typhoon Faith in the South China Sea. Acta Oceanologica Sinica, 2012, 31(2): 25. doi:10.1007/s13131-012-0189-9 | |

| 40. | Gang Wang, Fangli Qiao, Dejun Dai, et al. A possible generation mechanism of the strong current over the northwestern shelf of the South China Sea. Acta Oceanologica Sinica, 2011, 30(3): 27. doi:10.1007/s13131-011-0116-5 | |

| 41. | Baogang Jin, Guihua Wang, Yonggang Liu, et al. Interaction between the East China Sea Kuroshio and the Ryukyu Current as revealed by the self‐organizing map. Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans, 2010, 115(C12) doi:10.1029/2010JC006437 | |

| 42. | Gang Wang, Fangli Qiao, Yijun Hou, et al. Response of internal waves to 2005 Typhoon Damrey over the northwestern shelf of the South China Sea. Journal of Ocean University of China, 2008, 7(3): 251. doi:10.1007/s11802-008-0251-6 |

| Author(s) (year) | Horizontal scale/km | Vertical scale/m | Time scale/d |

| McWilliams (1985) | < first baroclinic radius of deformation | ||

| Capet et al. (2008a) | O(10) | O(10) | O(1) |

| Ferrari and Wunsch (2009) | 10–150 | ||

| Liu et al. (2010a) | O(1) | ||

| Callies and Ferrari (2013) | 1–200 | ||

| Callies et al. (2015) | 1–100 | ||

| McWilliams (2016) | 0.1–10 | 10–1 000 | hours-day |

| Sasaki et al. (2017) | 16–50 | ||

| Qiu et al. (2017) | 10–150 | ||

| Zheng (2017) | 1–200 | ||

| Zhong et al. (2017) | Rossby number O(1) | ||

| Renault et al. (2018) | 0.1–10 | ||

| Li et al. (2018) | O(0–10) | O(1) | |

| Dong and Zhong (2018) | Rossby number O(1) |

| Sub-categories | Phenomena/processes | Scales |

| Submesoscale waves | long internal waves | wavelength: 1–5 km, crest line: 10–200 km, |

| R0: 2–10 at 20°N | ||

| Internal tide* | Mode-1 M2: wavelength ~150 km, R0~0.5 | |

| near inertial waves* | wavelength: 10–20 km, R0 = O(1) | |

| instability/shear waves | ||

| Submesoscale vortexes | small eddies* | R0 = O(1) |

| coherent vortex train* | R0 = O(1) | |

| spiral train* | R0 = O(1) | |

| topographic wakes | ||

| Submesoscale shelf processes | small estuary plumes | R0 = O(0.5) |

| front* | frontal widths: 10–50 km | |

| horizontal wavelength: 20–40 km | ||

| vertical circulation* | ||

| offshore jet/filament | R0 = O(0.5) | |

| Submesoscale turbulence | Modeled submesoscale turbulence* | R0 = O(1) |

| Note: * Reviewed in this paper. | ||

| Author(s) (year) | Horizontal scale/km | Vertical scale/m | Time scale/d |

| McWilliams (1985) | < first baroclinic radius of deformation | ||

| Capet et al. (2008a) | O(10) | O(10) | O(1) |

| Ferrari and Wunsch (2009) | 10–150 | ||

| Liu et al. (2010a) | O(1) | ||

| Callies and Ferrari (2013) | 1–200 | ||

| Callies et al. (2015) | 1–100 | ||

| McWilliams (2016) | 0.1–10 | 10–1 000 | hours-day |

| Sasaki et al. (2017) | 16–50 | ||

| Qiu et al. (2017) | 10–150 | ||

| Zheng (2017) | 1–200 | ||

| Zhong et al. (2017) | Rossby number O(1) | ||

| Renault et al. (2018) | 0.1–10 | ||

| Li et al. (2018) | O(0–10) | O(1) | |

| Dong and Zhong (2018) | Rossby number O(1) |

| Sub-categories | Phenomena/processes | Scales |

| Submesoscale waves | long internal waves | wavelength: 1–5 km, crest line: 10–200 km, |

| R0: 2–10 at 20°N | ||

| Internal tide* | Mode-1 M2: wavelength ~150 km, R0~0.5 | |

| near inertial waves* | wavelength: 10–20 km, R0 = O(1) | |

| instability/shear waves | ||

| Submesoscale vortexes | small eddies* | R0 = O(1) |

| coherent vortex train* | R0 = O(1) | |

| spiral train* | R0 = O(1) | |

| topographic wakes | ||

| Submesoscale shelf processes | small estuary plumes | R0 = O(0.5) |

| front* | frontal widths: 10–50 km | |

| horizontal wavelength: 20–40 km | ||

| vertical circulation* | ||

| offshore jet/filament | R0 = O(0.5) | |

| Submesoscale turbulence | Modeled submesoscale turbulence* | R0 = O(1) |

| Note: * Reviewed in this paper. | ||