| Citation: | Gaolong Huang, Haigang Zhan, Qingyou He, Xing Wei, Bo Li. A Lagrangian study of the near-surface intrusion of Pacific water into the South China Sea[J]. Acta Oceanologica Sinica, 2021, 40(7): 15-30. doi: 10.1007/s13131-021-1766-6 |

The Luzon Strait, located between the Taiwan Island and Luzon Island, is a wide (approximately 360 km) meridional gap of the western Pacific boundary and the only deep (>2 000 m) channel connecting the South China Sea (SCS) and the Pacific Ocean. Leading considerable material and dynamical fluxes through the Luzon Strait, the intrusion of Pacific water significantly influences the hydrological characteristics, circulation patterns, eddy activities, and biological production of the Northern South China Sea (Qu et al., 2004; Cai et al., 2005; Nan et al., 2011b; He et al., 2016; Zhang et al., 2017).

The intrusion of Pacific water is closely related to the behavior of Kuroshio in the Luzon Strait. As the primary western boundary current (WBC) of the North Pacific subtropical gyre, the Kuroshio originates from the North Equatorial Current (NEC) bifurcation at approximately 10°N to 15°N (Nitani, 1972; Qiu and Chen, 2010). During its course northward, the Kuroshio usually bends clockwise into the Luzon Strait, with inflow and outflow through the Balintang and Bashi Channel, respectively. In the mean state, the Kuroshio axis is mainly confined within the Luzon Strait, indicating a gap-leaping path of the Kuroshio (Caruso et al., 2006; Liang et al., 2008; Lu and Liu, 2013). Lu and Liu (2013) suggested that the gap-leaping Kuroshio with a strong potential vorticity front can act as a dynamic barrier, blocking the westward propagation of Rossby waves and eddies from the Pacific. However, the Kuroshio occasionally meanders into the northeastern SCS in the form of a loop current, which is no longer restricted to the Luzon Strait (Li and Wu, 1989; Farris and Wimbush, 1996; Jia and Liu, 2004; Yuan et al., 2006; Liu et al., 2016; Zhang et al., 2017). Associated with the westward extension, part of the Kuroshio water can intrude deep into the SCS, primarily in winter. For example, early hydrographic studies by Shaw (1991) and Qu et al. (2000) observed the North Pacific high-salinity water on the continental slope of the northern SCS in winter. Centurioni et al. (2004) found that surface drifters deployed in the Pacific crossed the Luzon Strait and reached the inner SCS between October and January.

The Kuroshio is highly variable in the Luzon Strait. Previous satellite and in situ observations suggest that inflows and outflows in the upper layer of the Luzon Strait often appear alternately, exhibiting complicated spatial structures and temporal variability (Caruso et al., 2006; Tian et al., 2006; Yuan et al., 2006; Liang et al., 2008; Zhang et al., 2015). Even so, three descriptive flow patterns of Kuroshio intrusion have been frequently reported, including the Kuroshio intruding branch (KIB), Kuroshio loop current (KLC), and the associated shed eddy (KLC-SE). Early studies, primarily based on fragmentary hydrographic data, were limited to unveiling the overall structure and path transition of the Kuroshio. Recently, with the abundant availability of satellite observations and high-resolution models, KLC and KLC-SE are increasingly recognized to be only transient rather than persistent flow patterns that usually appear in winter (Yuan et al., 2006; Jia and Chassignet, 2011; Nan et al., 2011b; Zhang et al., 2017).

Observations of satellite-tracked Lagrangian drifters have increased around the Luzon Strait in the past decade. These drifters have been used to study features of regional circulation (Centurioni et al., 2004; Wang et al., 2008a; Guo et al., 2012; Qian et al., 2013) and eddy activities (Wang et al., 2008b; Huang et al., 2010; Li et al., 2011). The drifter trajectories could provide direct insights into the pathways of the Kuroshio and the intrusion of Pacific water into the SCS. Inspired by the results from the drifter observations, simulated Lagrangian particle sets were created to study the origins of the intrusion water. The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. The data and methods are described in Section 2. Results from the satellite-tracked drifters and simulated particles are presented in Sections 3 and 4, respectively. Conclusions are proviede in Section 5.

The Lagrangian drifter dataset is from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s (NOAA’s) Atlantic Oceanographic and Meteorological Laboratory (AOML) Global Drifter Program (GDP) Drifter Data Assembly Center (available online at

With drogues attached, the GDP drifters follow 15 m currents in the mixed layer. The migration of a drogued drifter is not sensitive to wind-induced slippage, which is less than 10−2 m/s for a wind speed of up to 10 m/s (Niiler et al., 1995). When the drogue is lost, the sampling level rises to the sea surface, resulting in a remarkably increased downwind slip. In this study region, undrogued data accounted for 43% of the total drifter observations. Here, we conducted wind-slip correction for the velocities of both drogued and undrogued drifters. The 6-h surface winds from NCEP/NCAR Reanalysis v.2 were linearly interpolated to the drifter positions. Then a downwind slip, denoted as

| $$ {A}_{\mathrm{u}}=\frac{ \left\langle { {U}_{\mathrm{u}} } \right\rangle -\left(\left\langle { {U}_{\mathrm{d}} } \right\rangle -{A}_{\mathrm{d}} \left\langle { W } \right\rangle \right)}{ \left\langle { W } \right\rangle }, $$ | (1) |

where U is the downwind component of the drifter velocities, the subscripts d and u denote drogued and undrogued drifters, respectively, and the bracket

The corrected drifter velocities were used to construct the quasi-Eulerian velocity field. First, by using a 9-point (equivalent to 2 d) running average filter, all velocities were low-pass filtered to remove tides and near-inertial variability. Second, the filtered velocities were grouped into 0.5°×0.5° bins. This bin size was chosen to reasonably reflect the spatial variation of major currents while ensuring sufficient drifter observations for statistical analysis. Within each bin, all the data were pre-averaged over a 7-d window, from which the ensemble mean was obtained. This averaging method can help avoid oversampling caused by slow-moving or retained drifters within a spatial bin (Niiler et al., 2003; Centurioni et al., 2008). Note that only the bins with more than five sampled windows were considered here.

The satellite altimeter-derived geostrophic velocities used in this study were processed by SSALTO/DUACS and distributed by Archiving, Validation and Interpretation of Satellite Oceanographic Data (AVISO,

| $$ {\boldsymbol{V}}_{{g}}=\frac{-g}{f}{{\boldsymbol{k}}}\times \nabla \eta, $$ | (2) |

where

To conduct wind-slip correction for GDP drifters and to estimate the Ekman component of the flow, a 10 m height wind speed product was used: the NCEP/NCAR Reanalysis v.2 (

| $$ \text{τ}={\rho }_{{\rm{a}}}{C}_{{{\rm{d}}}}{\boldsymbol{W}}\left|{\boldsymbol{W}}\right|, $$ | (3) |

where

| $$ {10}^{3}{C}_{\mathrm{d}}=\left\{ \begin{array}{l}0.49+0.065\left|{\boldsymbol{W}}\right|,\;\;\;\;\;\;\;\left|{\boldsymbol{W}}\right|>10\;{\rm{m}}/{{\rm{s}}},\\ 1.14,\;\;\;\;\;\;\;\;\;\;\;\;\;\;\;\;\;\;\;\;\;\;\;\;\;\;\;3\leqslant \left|{\boldsymbol{W}}\right|\leqslant 10\;{\rm{m}}/{{\rm{s}}},\\ 0.62+1.56/\left|{\boldsymbol{W}}\right|,\;\;\;\;\;\;\;\left|{\boldsymbol{W}}\right|< 3\;{\rm{m}}/{{\rm{s}}}.\end{array} \right. $$ | (4) |

Then, the Ekman velocity was estimated using the formula of Ralph and Niiler (1999):

| $$ {V}_{{{\rm{e}}}}=\frac{\beta {{\rm{e}}}^{-{\rm{i}}\theta }}{\sqrt{f\rho }}\frac{\boldsymbol{\text{τ} }}{\sqrt{\left|\boldsymbol{\text{τ} }\right|}}, $$ | (5) |

where

To better understand transport patterns in the study region, the simulated particle data set was obtained under the Lagrangian framework:

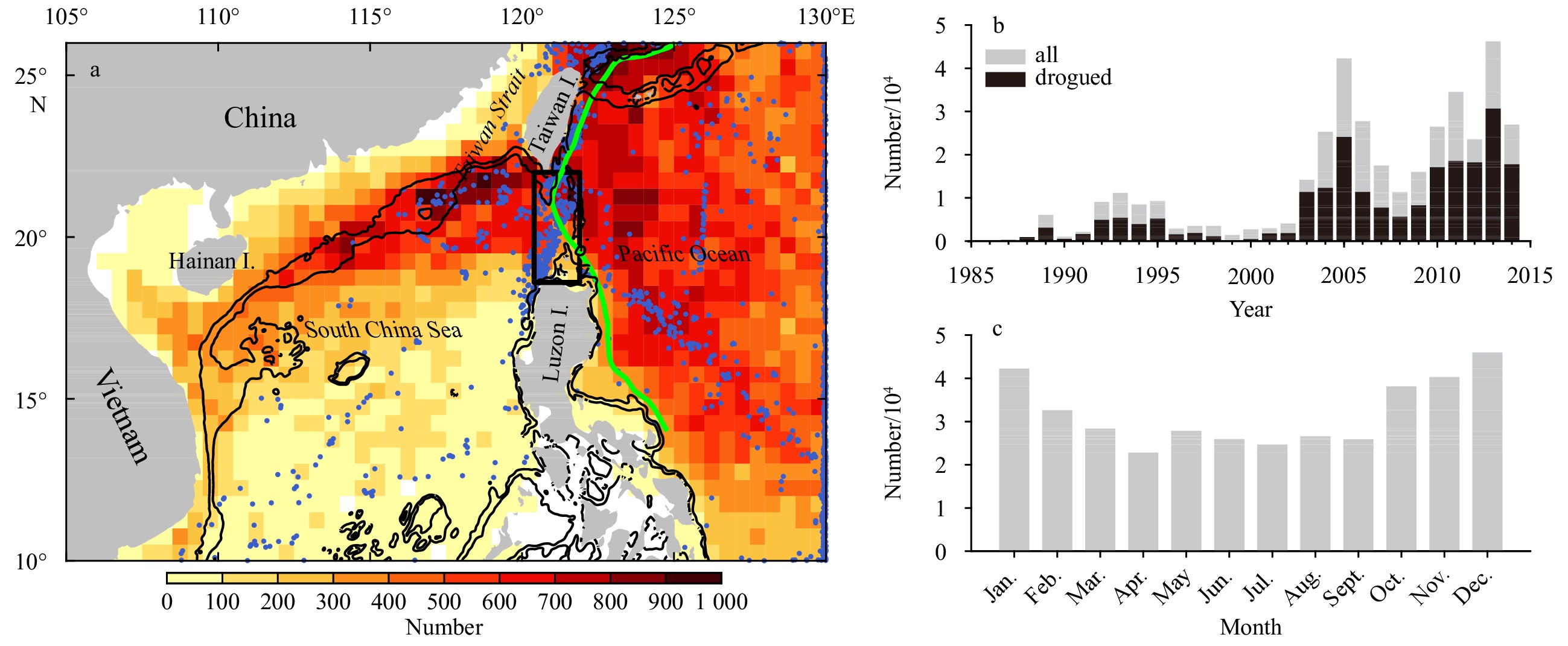

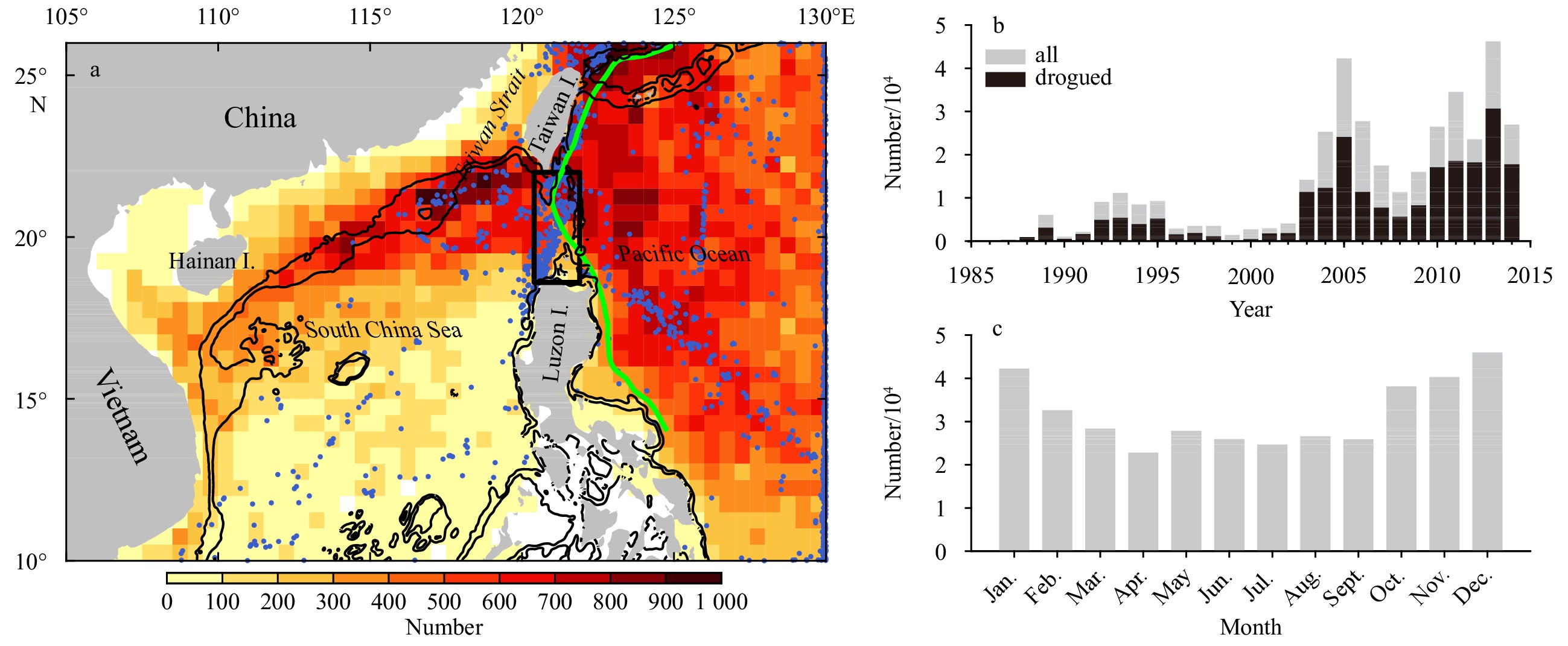

The spatial and temporal distributions of drifter observations are shown in Fig. 1. Between 1986 and 2014, 1031 drifters were launched inside and 548 were drifted into the study region. The distribution of drifter observations is highly uneven in time and space. Only 150 drifters were launched before 2003. In the following decade, drifter launches increased significantly due to several specific experiments that focused on investigations of the Kuroshio in the Luzon Strait, seasonal circulation, and mesoscale variability around the northern SCS and Taiwan Island (Rudnick et al., 2011). Concentrated launches can be easily found in the above regions (Fig. 1a). In fact, about 82% of our observations were collected between 2003 and 2014 (Fig. 1b).

Pathways of surface water can be reflected by certain selections of trajectories of drifters that were launched or drifted into specific areas. In this study, the Luzon Strait is defined as a rectangular region 18.6°–22.0°N, 120.4°–121.9°E, (Fig. 1a). The latitudes of the southern and northern boundary of the strait are determined by the locations of the northern tip of Luzon Island and the southern tip of Taiwan Island, respectively. We made the same choice of longitudes of the eastern and western boundaries as Guo et al. (2012): the eastern boundary crosses Babuyan Island and the western boundary is the westernmost limit of the leap-type trajectories in the Luzon Strait.

To examine the pathways of Pacific water in the Luzon Strait, we selected trajectories of drifters that originated from the Pacific and subsequently reached the strait. A total of 231 such trajectories are found and colored according to distinct pathways near the strait (Fig. 2). The intrusion of Pacific water has remarkable seasonal features as revealed by the selected trajectories. During wintertime, 162 drifters were entrained into the strait from the Pacific and 74 of them moved to the SCS without returning (Fig. 2b). However, only 9 out of the 69 drifters intruded into the SCS during summertime (Fig. 2a). Except for one drifter (ID 81890) that went through the Luzon Strait in mid-May and then crossed the 23.5°N section of the Taiwan Strait in late June, all other intrusions occurred after late September, when the northeast monsoon prevails over the Luzon Strait. This result of robust seasonal intrusion is consistent with the early study of Centurioni et al. (2004), even though the number of intrusion drifters in our study is five times greater.

The intrusion drifters, a total of 83, usually experienced strong westward currents during their course through the strait. Although the mean zonal crossing speed is only (0.52±0.26) m/s, the maximum westward speeds measured by each drifter range from 0.70 m/s to 1.93 m/s, with an average value of (1.05±0.26) m/s. Nearly 60% of the intrusion drifters crossed the strait (about 150 km in zonal width) within 4 d and 7 of them crossed within 2 d. We note that the spreading of the intruded drifters in the SCS is remarkably steered by the bottom topography. As shown in Fig. 2b, the northward spreading is largely confined to the south of the northeastern corner of the SCS basin. Only three drifters passed through the 24°N section in the Taiwan Strait and traveled northward. The majority of the intruded drifters flowed southwestward along the continental slope of the northern SCS. Few drifters arrived at the central SCS and the only southward pathway was along the narrow shelf off Vietnam. The strong Vietnam jet was observed by 35 intruded drifters, with an average southward velocity of (1.23±0.5) m/s when crossing the 13°N section. Such topographic steering is probably closely related to the wintertime western boundary currents (Figs 3a and d) in the SCS. LaCasce (2008) suggested that passive ocean floats, including surface drifters, have a statistical tendency to follow the contours of barotropic f/H (Coriolis parameter/water depth), which provides a restoring force to support Rossby and topographic waves. The drifter spreading may also be sensitive to Ekman drift, stratification, and forcing of the shelf zones; the complete dynamics causing the spreading of the drifters in the SCS are beyond the scope of this study.

Besides the 83 intrusion drifters, there are also 148 drifters that entrained into the Luzon Strait from the Pacific and subsequently traveled back into the Pacific. Most of these drifters leaped directly across the strait, while a few looped westward into the SCS. By inspecting the trajectory clusters near the Luzon Strait, we chose the westernmost longitude of the trajectory with ID 7710570, shown in Fig. 2a, to define the western boundary of the strait and to separate the loop-type trajectories from the leap-types. This choice of the western limit of the Luzon Strait is somewhat subjective; however, a small change would not affect the main results, considering the low proportion of loop-type trajectories. A total of 10 loop-type trajectories were identified, with 5 trajectories in each season (Figs 2a and b). Nevertheless, by comparisons with the contemporaneous geostrophic velocity fields, we find that only three drifters (two with drogues attached) followed independent KLCs, which all formed in wintertime. The others were entrained to the west of the strait by the Kuroshio and experienced local submesoscale or mesoscale movements. For example, the westernmost (~119.2°E) reaching drifter in summertime (Fig. 2b) was captured by an anticyclonic eddy in July and returned to the Pacific after two loops were completed in the SCS.

The above results show that for drifters that were entrained into the Luzon Strait from the Pacific, approximately 60% of them directly leaped across the strait, 36% intruded into the SCS, and only 4% underwent a looping pathway. In fact, as discussed in the next section, the undrogued drifters constitute a large proportion of the intrusion drifters, leading to an overestimation of the probability of the intrusion of Pacific water. The probability of KLC estimated in previous studies ranges between 14.1% and 25.0% (Nan et al., 2011a; Huang et al., 2016); however, the KLC-related loop-type trajectories are rather rare from drifter observations in this study. A possible reason may be that during the emergence of KLC, drifters that followed the eastern flank of the loop current, fell into the leap-type owing to their limited westward displacements. For drifters that were entrained in the western flank, their movements are likely to be subject to the unstable flows near the frontal region, resulting in separation from the loop current. It is also worth pointing out that for undrogued drifters, the downwind slip velocity could reach more than 0.1 m/s in the northeast monsoon period, enough to alter the pathway of the drifter around the turning region of the loop current.

It has been shown that a small part of drifters from the Pacific could loop to the west of the Luzon Strait or travel northward to the Taiwan Strait during the summertime monsoon. Such summertime intrusions may be attributed to the instability of the Kuroshio front or eddy-Kuroshio interactions on both sides of the strait. However, the summertime circulation in the northeastern SCS (Figs 3b and c) does not seem to favor the westward intrusion of drifters to the interior of the SCS. Drifters that arrived at the southwest of Taiwan Island have the chance to be entrained in the northeastward Taiwan Warm Current (Shaw, 1991). And drifters that arrived at the northeast of Luzon could be carried into a northeastward outflow of the SCS (Figs 3b and c), then follow the Kuroshio to get to the southeast of Taiwan Island. This summertime SCS outflow was also suggested by the studies of Liang et al. (2008) and Nan et al. (2011b). Hydrographic research by Rudnick et al. (2011) found that the salinity in the upper 50 m layer southeast of Taiwan Island is lower in summer than in winter, supporting the existence of this outflow. From the trajectory results, we found that approximately twenty drifters that were launched in the SCS and traveled into the Pacific through the Luzon Strait took a narrow exit southeast of Taiwan Island in summertime (figures not shown).

Figure 2c shows the trajectories of 273 drifters launched in the Luzon Strait. Here, we focused on 147 drifters that directly intruded or looped into the SCS. Most of them were launched during the wintertime between 2003 and 2006. Their spreading in the SCS is similar to that of the intrusion drifters from the Pacific (Fig. 2b), exhibiting salient characteristics of topographic steering. Nonetheless, this drifter set is not suitable for the analysis of the intrusion of Pacific water, as the water in the Luzon Strait could be either from the Pacific or the SCS. Their pathways seem to be closely related to launch locations because 90% of them were launched south of the deep Balintang Channel (~20.5°N), where the Kuroshio primarily flows into the Luzon Strait (Liang et al., 2008). In addition to the intruded Kuroshio, these drifters could also be entrained into the SCS by the local northwest flows (Figs 3a and d), which may be part of the SCS cyclonic gyre (Liang et al., 2008; Wang et al., 2012). In southwest Taiwan Island, there are 20 loop-like trajectories that are mostly confined to the east of 119°E. These drifters reflect more obvious features of KLCs than the loop-type ones from the Pacific. However, it should be noted that some of them might follow water mass from the SCS, since the KLCs could carry some SCS water inside during the westward looping process (Zhang et al., 2017).

To explore the origins of the near-surface intrusion water from the intertwined drifter trajectories, we constructed an intrusion probability map based on drifters from the Pacific (Fig. 4a). In each 0.25°×0.25° bin, the intrusion probability is calculated straightforwardly by dividing the total number of drifters that passed through the bin by the number of drifters that passed through the bin and intruded into the SCS later. Only bins crossed by more than ten different drifters were considered. The probability map in Fig. 4a indicates that the intrusion drifters can be traced back to a wide area east of the Luzon Strait. As expected, a high probability curved band is found near the origin and upstream region of the Kuroshio. Noticeably, elevated probabilities (larger than 0.2) also exist in regions away from the Kuroshio. For instance, a lobe of enhanced probability is located east of the Luzon Strait (centered about 20°N, 125°E) and below it there are two high-value streaks stretching eastward beyond 130°E. We also note that the intrusion probabilities increased rapidly after the drifters crossed the mean Kuroshio core (green line in Fig. 2a) in the Luzon Strait, indicating the strong barrier effect of the Kuroshio.

In previous studies, the intrusion of Pacific water is often simply presented as the Kuroshio Intrusion or the net westward Luzon Strait Transport (LST). The above results of the intrusion probability map led us to investigate how much other Pacific water could enter the SCS, except for the Kuroshio Intrusion water. To investigate this, we plotted the trajectories of intrusion drifters 15 d before and after crossing 120.8°E in the Luzon Strait (Fig. 4b). The resultant intrusion trajectories present a forked-fishtail shape near the entrance of the strait. Accordingly, two sections were defined. A subset of the intrusion drifters (a total of 41 drifters) followed the path of the Kuroshio Current northeast of Luzon Island, and crossed or launched near the section at 18.5°N between 122.3°E and 124.0°E (hereinafter referred to as the KC section, Fig. 4c). The others (a total of 42) came from the east of the Luzon Strait and crossed or were launched near the section at 124.0°E between 18.5°N and 23.0°N (hereinafter referred to as the LSE section, Fig. 4d).

Except for drifters entrained into the upstream Kuroshio northeast of Luzon Island, nearly half of the intrusion drifters originated from a wide area east of the Luzon Strait. This subset of drifters could be carried westward to the strait by zonal jets, mesoscale eddies, or surface Ekman currents, and then penetrated into the SCS when the Kuroshio intrusion occurred. The downwind slip may also have a considerable contribution to the westward displacement of the undrogued drifters. We found that approximately 73% of the intrusion drifters had lost their drogues before they entered the strait (Figs 4c and d).

To better understand the intrusion behavior, we examined the velocity components of the drifter data. As per Brambilla and Talley (2006), the drifter velocity

| $$ \boldsymbol{V}\left(t\right)={\boldsymbol{V}}_{{{\rm{g}}}}\!\left(t\right)+{\boldsymbol{V}}_{\rm{E}}\!\left(t\right)+{\boldsymbol{V}}_{\rm{a}\rm{g}}\!\left(t\right)+{\boldsymbol{V}}_{\rm{s}\rm{l} \rm{i}\rm{p}}\!\left(t\right), $$ | (6) |

where

Figure 5a shows the mean geostrophic velocity field in wintertime. The AVISO velocities can resolve flow features that are 100 km and larger and can effectively capture variations of major currents and mesoscale processes. As we can see, circulation patterns near the Luzon Strait, including the Kuroshio pathway, are largely consistent with those of the drifter velocities (Figs 3a and d). For the Kuroshio in the Luzon Strait and currents in the northeastern SCS, the magnitude of the geostrophic velocities is weaker than those estimated from the drifters. This can be partly attributed to the absence of Ekman velocities, which can be larger than 0.1 m/s in these areas (Fig. 5b).

To investigate the mesoscale processes, the eddy kinetic energy (EKE) is calculated based on the geostrophic velocities,

An approach to examine the features of recirculation and eddies from drifter data is to extract segments of closed loops from drifter trajectories. Only trajectories originating from the Pacific are used and loops are extracted after filtering out inertial movements (Fig. 2d). The distribution of these loops is similar to that of EKE, reflecting strong activities of eddies east of the Luzon Strait and southwest of Taiwan Island, as well as recirculation near the eastern flank of the Kuroshio. In contrast, a narrow band with few loops exists east of Luzon Island and Taiwan Island, suggesting a stable pattern of the Kuroshio in these areas. For drifters east of the strait, including those trapped by eddies, loop movements are supposed to increase their probability of intrusion, owing to extended residence time. Nevertheless, the available loop observations seem to be insufficient to support the viewpoint that eddies from the Pacific could penetrate into the SCS because few loops are found in the Luzon Strait and to the left of it, while the anti-clockwise loops southwest of Taiwan Island actually reflect features of KLC-SEs or local anticyclonic eddies.

Figure 5b shows that the wintertime mean Ekman currents around the Luzon Strait are generally northwestward with an amplitude of approximately 0.1 m/s. As the local Ekman current is much weaker than the Kuroshio, the direct contribution of Ekman transport to the LST is small (Qu et al., 2004; Liang et al., 2008). Nevertheless, the cumulative effect of Ekman drift should not be ignored. The Pacific water east of the strait could be consecutively entrained westward into the Kuroshio by the steady Ekman drift. For drifters, the wind-induced westward speed of undroged ones is nearly double that of drogued ones. Figures 5c and d show the mean fields of residual velocity

An interesting result in Fig. 5d is that there are unusually high residual velocities north of Luzon Island. We found that this is a result of a strong westward jet, which was mainly measured by intruded undrogued drifters. Six drifters (two with drogues, shown in Fig. 4c) followed this jet and entered the SCS in five different years. This subset of drifters measured the swiftest westward motions in the Luzon Strait, with mean and maximum westward speeds of 0.8 m/s and 1.93 m/s, respectively. However, this narrow, near-coastal jet was barely resolved by geostrophic velocities. Based on trajectory observations, we presume that this jet was separated from the Kuroshio after the northward Kuroshio was squeezed by the steep topography.

Another possible source of intrusion water is a westward current centered at about 20°N east of the Luzon Strait (Fig. 3d). This current, first observed by Centurioni et al. (2004), usually occurred between October and December with mean westward speeds ranging from 0.2 m/s to 0.35 m/s. It was termed as the westward limb of the Wintertime Subtropical Current (WSTC), which was proven to be an independent current rather than the north branch of the NEC (Lee and Centurioni, 2013). Figure 3d shows that the WSTC fed into the Kuroshio and appeared as part of an anticyclonic recirculation east of the Luzon Strait and Taiwan Island. Evidently, drifters aggregated in these regions, resulting in the highest drifter density in all seasons.

To address the impact of possible undersampling, short lifetimes, and effects of the Ekman and downwind slip velocities on the near-surface drifter trajectories, we created simulated trajectory sets based on various assumed flow fields constructed from the AVISO geostrophic velocities. Inspired by the distribution of real drifter trajectories, simulated particles are released weekly from two particular bands: a zonal band next to the KC section (referred to as the KC band) and a meridional band next to the LSE section (referred to as the LSE band), as shown in Fig. 6a. Particles were tracked forward for 150 d using the method described in Section 2.4. During 1993 to 2014, a total of 6.1×104 and 15.5×104 trajectories were obtained from the KC and LSE bands, respectively. We chose 150 d of integration because it is long enough for the study of intrusion problem as seen below.

A combination of the AVISO-based geostrophic velocities and the NCEP-based Ekman velocities were used for the computations of simulated trajectories because this velocity field, denoted AVISO-NCEP, could largely represent realistic near-surface currents measured by drifters (Fig. 5c). Figure 6b displays a subset of 150-d trajectories of 54 particles released from the KC band and advected within the AVISO-NCEP velocity field. The most striking feature in Fig. 6b is the sensitivity of the fates of individual particles to their release positions. Particles from the narrow KC band sample different parts of the Kuroshio and undergo very different pathways, reflecting the three typical paths of the Kuroshio in the Luzon Strait. Several particles seem to separate from a loop current and intrude into the SCS; and a few of them reach the coast of Vietnam following the wintertime boundary currents.

To quantify the distribution of the simulated particles from their source band, we constructed a probability map that shows the probability of a particle to visit different geographical locations after its release (Rypina et al., 2014). By dividing the study area into a small box, the visitation probability in each box (i, j) was estimated as the percentage of trajectories that visit this box at any time,

Figure 7 shows probability maps (with 0.5°×0.5° boxes) for particles on Days 30, 60, 90, 120, and 150 after they are released from the KC and LSE bands. Note that for visual purposes, we use a logarithmic color scheme for probability maps (i.e.,

As most of the concern is for the intrusion of Pacific water, statistical surveys are performed to obtain the percentage of intrusion particles. Only those particles that enter the SCS through the Luzon Strait and do not turn back into the Pacific within one month are considered as intrusion particles. This criterion can exclude particles that undergo looping pathways. The results of the intrusion percentages are shown in Fig. 8. As expected, the intrusion percentage increased with time, and on Day 150, it reached 29.2% for particles from the KC band; however it was only 4.5% for particles from the LSE band. Figure 8 also suggests a faster timescale of intrusion for particles from the KC band than for those from the LSE band. One can imagine that particles carried by the Kuroshio can enter the SCS directly during the Kuroshio intrusion events. It was found that among intrusion particles from the KC band, more than 80% of them enter the SCS within 30 d. Meanwhile, some particles that are likely to be influenced by local recirculation gyres or mesoscale eddies, might enter the SCS after a long lingering path east of the Luzon Strait. In fact, nearly a quarter of the intrusion particles from the LSE band remain in the Pacific even 60 d after their release. Note that theoretically, the intrusion percentage could continue to increase over time as long as particles exist east of the Luzon Strait. Therefore, a longer lifetime of a particle should correspond to a more stable value of the intrusion percentage but also a greater computation load. We found that a 150-d lifetime was long enough for our study. The growth rate of the intrusion percentage is small from Day 120 to Day 150 (only 2% and 6% for particles from the KC and LSE bands, respectively).

Another concern of this section is the exploration of the effects of wind-induced velocities, including Ekman velocities and downwind slip velocities, on the statistical features of the near-surface simulated particles. Based on two different velocity fields, we obtained two simulated trajectory sets using the same methods and parameters for the AVISO-NCEP trajectories described above. One velocity field is simply the AVISO-based geostrophic velocity field, denoted as AVISO-only and the other is a blended field composed of the AVISO-based geostrophic velocities, NCEP-based Ekman velocities, and downwind slip velocities, denoted as AVISO-NCEP-slip. In the computation of downwind slip velocities, the slip coefficient is set to 1.37×10–2, the same as the estimated value for undrogued drifters. A comparison indicated (Fig. 8) that the overall intrusion percentage for particles in the AVISO-NCEP field is nearly twice that in the AVISO-only field, where Ekman velocity is absent. As for particles in the AVISO-NCEP-slip field, on Day 150, the intrusion percentage for those from the KC band is 50.2%, 1.7 times that in the AVISO-NCEP field while the intrusion percentage for those from the LSE band reaches 21.3%, almost 5 times that in the AVISO-NCEP field.

Therefore, the simulation results above support our hypothesis in Section 3.2 that the Ekman drift could significantly contribute to the intrusion of Pacific water and that the undrogued drifters have a much greater chance of intrusion under the additional effect of downwind slip. Our analysis of simulated trajectories also leads to another finding that wind-induced velocities could affect the lateral distribution of intrusion trajectories in the SCS. Figure 9 displays probability maps for the 150-d trajectories corresponding to three different velocity fields. Differences between probability maps in shape and magnitude suggest that wind-induced velocities can contribute to the southwestward spreading of intrusion trajectories along the shelf zones of the northeastern SCS and can increase the proportion of particles that reach the southern SCS. The results from top panel of Fig. 9 imply that beneath the Ekman layer, intrusion water from the Pacific could be largely restricted to flow around the northeastern SCS.

In this section, we use flux-tagged particles to quantitatively estimate the near-surface intrusion flux through the Luzon Strait and to track its origins in the Pacific. Similar Lagrangian approaches have been applied to study transport pathways between the Pacific and Indian Ocean (van Sebille et al., 2014). In our study, particles were initially lined up on a meridional section in the Luzon Strait (between 18.6°N and 22.0°N at 120.8°E, shown in Fig. 6a) with a spacing of (1/10°). They are released weekly and advected within the velocity data only if the local velocity is westward. Particles are tracked 90 d backward and 30 d forward. Only those that originate in the Pacific and end up in the SCS are considered. These intrusion particles are assigned an intrusion flux, which is the local westward velocity times the length of particle spacing in the Luzon Strait. As a result, the total intrusion flux in each release is the sum of the flux carried by the intrusion particles. To track the origins of the intrusion flux, intrusion particles are classified into two groups depending on which section (i.e., the KC or LSE section) they cross before intruding into the SCS, thereby obtaining the corresponding intrusion flux from each section.

Figure 10 shows the time series of the intrusion flux from the KC and LSE sections. Here, particles are advected within the AVISO-NCEP velocity fields between 1993 and 2014. Over the 22 years, the mean intrusion flux from the KC section is 2.9×104 m2/s, with a standard deviation of 2.4×104 m2/s and the mean intrusion flux from the LSE section is only 0.4×104 m2/s, with a standard deviation of 1.0×104 m2/s. Both the intrusion flux from the KC and LSE sections exhibit strong submonthly and seasonal variations. However, there is a much larger interannual variability in the intrusion flux from the LSE section. High values of the intrusion flux from the LSE section occur during 1994–1997, 2004–2005, and 2011–2012. In other years the intrusion flux from the LSE section is much smaller than that from the KC section.

Simulation results indicate that, except for the Kuroshio intrusion water, a certain amount of other Pacific water can intrude into the SCS. In our preliminary estimation, this water constituted only about 13% of the total intrusion flux in the Luzon Strait on average. Even so, in some years, their contribution to intrusion water is quite considerable, for example, reaching more than 35% during the winter of 1994–1995. Like drifters discussed in Section 3, these water could be carried westward by zonal jets, Ekman currents, or eddies. The interannual signal in their corresponding intrusion flux might be closely related to variations in the WSTC transport and eddy activities east of the Luzon Strait. According to a previous study by Lee and Centurioni (2013), the WSTC Sverdrup transport reached an all-time maximum during 1994–1997. Meanwhile, during the same period, the intrusion flux from the LSE section is relatively large (Fig. 10). By inspecting the velocity fields, we find that strong intrusion events during 2004–2005 seem to be caused by unusually strong eddy activities east of the Luzon Strait. Sun et al. (2016) found that the maximum peak-to-tough amplitude of EKE in the northeastern SCS also occurred during 2004–2005, indicating that the interannual signal of eddy activities may have propagated into the SCS via enhanced intrusion water.

From Fig. 10, we can also see that in individual intrusion events the intrusion flux from the LSE section can be rather large, and in a few cases even larger than 4×104 m2/s. These strong intrusion events are often related to eddy activities because direct contributions from zonal jets and Ekman currents to intrusion flux are limited. One of the eddy-related intrusion events is studied here. To show the detailed processes of the intrusion of Pacific water and the eddy-Kuroshio interaction, we compute Lagrangian longitude maps, in which longitudes are treated as tracers. Initially, simulated particles are uniformly seeded in the domain under this study, and then advected backward in time within the AVISO-NCEP velocity field. The final longitude that each particle is tracked back to after a period of integration is coded by color. Here, we choose a 45 d integration as it is long enough for our study.

Figure 11 shows longitude maps between December 16, 2003 and January 10, 2004, during which (also denoted by a yellow line in Fig. 10) a westward-propagating cyclonic eddy interacted with the Kuroshio. Transport patterns visualized by longitude maps are complicated. The domain under study is filled with entangled Lagrangian structures from mesoscale to submesosale. Nevertheless, coherent structures of eddies and loop currents can be identified, and intrusion water mass can be distinguished by colored longitudes. On December 16, 2003, a cyclonic eddy approached the Kuroshio northeast of Luzon Island. Before interacting with this eddy, the Kuroshio had already intruded into the SCS, with some of its water deep into the shelf zone of the SCS and the rest taking a loop path southwest of Taiwan Island. Meanwhile, some Pacific water (dark gray) carried by westward flows encountered the Kuroshio at about 20°N. Most of them fed into the Kuroshio east of Taiwan Island; only a few had a trip into the SCS flowing the loop current. From the longitude map on December 23, 2003, we found that water from the outer part of the eddy could be entrained into the Kuroshio and then intruded into the SCS; however, the intrusion of other Pacific water did not occur. As the eddy-Kuroshio interaction continued, the cyclonic eddy propagated further west and pushed more of the Kuroshio into the Luzon Strait. On December 30, 2003, plenty of Pacific water intruded into the SCS, exceeding the amount of Kuroshio intrusion water. In this individual event, there seem to be three origins for the intrusion water: the Kuroshio, the cyclonic eddy, and westward flows. It is hypothesized that the cyclonic eddy blocked the Kuroshio in the Luzon Strait, and facilitated the intrusion of the westward Pacific water. The eddy dissipated quickly after January 10, 2004. They were elongated in the zonal direction and cut into two parts by the northward Kuroshio. The smaller western part intruded into the SCS and the eastern part was carried northward and subsequently disappeared.

Based on historical satellite-tracked drifter observations, the transport pathways of near-surface water around the Luzon Strait are investigated, while focusing on the intrusion of Pacific water into the SCS. It was found that almost all intrusions of drifters from the Pacific to the SCS occurred during the northeast monsoon. The spreading of intrusion drifters in the SCS seems to be strongly steered by the topography. The statistical results of drifter pathways indicate that the KLC-related loop-type trajectories are rare. In summertime, weak intrusions were observed and drifter observations support the existence of the SCS outflow. We also found a narrow wintertime jet near the northern coast of Luzon Island. This strong westward jet is likely to be separated from the Kuroshio.

The results regarding the origins of intrusion drifters suggest that except for the Kuroshio intrusion water, other Pacific water carried by zonal jets, Ekman currents, or eddies, can also intrude into the SCS. Statistical results of simulated trajectories indicate that the Ekman drift could significantly contribute to the intrusion of Pacific water and could influence the spreading of intrusion water in the SCS. In our preliminary estimation, the other Pacific water constituted about 13% of the total near-surface intrusion flux in the Luzon Strait on average. In some years and multiple individual intrusion events, their contribution to intrusion water was quite considerable. The interannual signal in their corresponding intrusion flux might be closely related to variations in the WSTC transport and eddy activities east of the Luzon Strait. To show the detailed processes of the intrusion of the Pacific water and the eddy-Kuroshio interaction, a case study of an eddy-related intrusion is presented.

Lagrangian approaches allow us to effectively separate the Kuroshio intrusion flux from the total flux of the Luzon Strait. It is helpful to analyze the temporal variation of the Kuroshio intrusion which was usually quantified by the LST or different types of Kuroshio intrusion indices in previous studies. The seasonal cycle of the Kuroshio intrusion is generally attributed to the seasonally reversing monsoon. However, the interannual variation of the Kuroshio intrusion is less understood, and has been found to be related to various climate indices, such as the El Niño-Southern Oscillation (ENSO), the Philippines-Taiwan Oscillation (PTO), and the Pacific Decadal Oscillation (PDO) (Kim et al., 2004; Qu et al., 2004; Chang and Oey, 2012; Wu, 2013; Yu and Qu, 2013). Relationships between the Kuroshio intrusion and these indices are usually built through the meridional migration of the NEC bifurcation due to changes in the wind forcing in the Pacific. Other factors may also affect the interannual variation of the Kuroshio intrusion. The WSTC transport and eddy activities east of the Luzon Strait have been found to be connected to the interannual signal in the intrusion flux of non-Kuroshio Pacific water. However, their contribution to Kuroshio intrusion on the interannual timescale remains unclear.

It should be noted that our quantitative results regarding the intrusion of Pacific water from simulated trajectories are limited to the near-surface layer. It can be speculated that the effect of the Ekman drift on the intrusion of Pacific water could be ignored beneath the Ekman layer. The contribution of non-Kuroshio Pacific water to the total intrusion flux in the Luzon Strait varies with depth. It might get considerably large at some level where the Kuroshio becomes weak and the associated transport barrier breaks down under the impact of westward currents or eddies. Therefore, estimates of the volume transport of Pacific intrusion water in different layers should be carried out in future studies.

The numerical simulation is supported by the High Performance Computing (HPC) Division and HPC managers of Wei Zhou and Dandan Sui in the South China Sea Institute of Oceanology.

| [1] |

Brambilla E, Talley L D. 2006. Surface drifter exchange between the North Atlantic subtropical and subpolar gyres. Journal of Geophysical Research, 111(C7): C07026

|

| [2] |

Cai Shuqun, Liu Hailong, Li Wei, et al. 2005. Application of LICOM to the numerical study of the water exchange between the South China Sea and its adjacent oceans. Acta Oceanologica Sinica, 24(4): 10–19

|

| [3] |

Caruso M J, Gawarkiewicz G G, Beardsley R C. 2006. Interannual variability of the Kuroshio intrusion in the South China Sea. Journal of Oceanography, 62(4): 559–575. doi: 10.1007/s10872-006-0076-0

|

| [4] |

Centurioni L R, Niiler P P, Lee D K. 2004. Observations of inflow of Philippine sea surface water into the South China Sea through the Luzon Strait. Journal of Physical Oceanography, 34(1): 113–121. doi: 10.1175/1520-0485(2004)034<0113:OOIOPS>2.0.CO;2

|

| [5] |

Centurioni L R, Ohlmann J C, Niiler P P. 2008. Permanent meanders in the California current system. Journal of Physical Oceanography, 38(8): 1690–1710. doi: 10.1175/2008JPO3746.1

|

| [6] |

Chang Yulin, Miyazawa Y, Guo Xinyu. 2015. Effects of the STCC eddies on the Kuroshio based on the 20-year JCOPE2 reanalysis results. Progress in Oceanography, 135: 64–76. doi: 10.1016/j.pocean.2015.04.006

|

| [7] |

Chang Yulin, Oey L Y. 2012. The Philippines-Taiwan oscillation: monsoonlike interannual oscillation of the subtropical-tropical western north pacific wind system and its impact on the ocean. Journal of Climate, 25(5): 1597–1618. doi: 10.1175/JCLI-D-11-00158.1

|

| [8] |

Farris A, Wimbush M. 1996. Wind-induced Kuroshio intrusion into the South China Sea. Journal of Oceanography, 52(6): 771–784. doi: 10.1007/BF02239465

|

| [9] |

Guo Jingsong, Chen Xianyao, Sprintall J, et al. 2012. Surface inflow into the South China Sea through the Luzon Strait in winter. Chinese Journal of Oceanology and Limnology, 30(1): 163–168. doi: 10.1007/s00343-012-1056-4

|

| [10] |

Hansen D V, Poulain P M. 1996. Quality control and interpolations of WOCE-TOGA drifter data. Journal of Atmospheric and Oceanic Technology, 13(4): 900–909. doi: 10.1175/1520-0426(1996)013<0900:QCAIOW>2.0.CO;2

|

| [11] |

He Qingyou, Zhan Haigang, Cai Shuqun, et al. 2016. Eddy effects on surface chlorophyll in the northern South China Sea: mechanism investigation and temporal variability analysis. Deep Sea Research Part I: Oceanographic Research Papers, 112: 25–36. doi: 10.1016/j.dsr.2016.03.004

|

| [12] |

Huang Bangqin, Hu Jun, Xu Hongzhou, et al. 2010. Phytoplankton community at warm eddies in the northern South China Sea in winter 2003/2004. Deep Sea Research Part II: Topical Studies in Oceanography, 57(19–20): 1792–1798. doi: 10.1016/j.dsr2.2010.04.005

|

| [13] |

Huang Zhida, Liu Hailong, Hu Jianyu, et al. 2016. A double-index method to classify Kuroshio intrusion paths in the Luzon Strait. Advances in Atmospheric Sciences, 33(6): 715–729. doi: 10.1007/s00376-015-5171-y

|

| [14] |

Jia Yinglai, Chassignet E P. 2011. Seasonal variation of eddy shedding from the Kuroshio intrusion in the Luzon Strait. Journal of Oceanography, 67(5): 601–611. doi: 10.1007/s10872-011-0060-1

|

| [15] |

Jia Yinglai, Liu Qinyu. 2004. Eddy Shedding from the Kuroshio Bend at Luzon Strait. Journal of Oceanography, 60(6): 1063–1069. doi: 10.1007/s10872-005-0014-6

|

| [16] |

Kim Y Y, Qu Tangdong, Jensen T, et al. 2004. Seasonal and interannual variations of the North Equatorial Current bifurcation in a high-resolution OGCM. Journal of Geophysical Research, 109(C3): C03040

|

| [17] |

LaCasce J H. 2008. Statistics from Lagrangian observations. Progress in Oceanography, 77(1): 1–29. doi: 10.1016/j.pocean.2008.02.002

|

| [18] |

Large W G, Pond S. 1982. Sensible and latent heat flux measurements over the ocean. Journal of Physical Oceanography, 12(5): 464–482. doi: 10.1175/1520-0485(1982)012<0464:SALHFM>2.0.CO;2

|

| [19] |

Laurindo L C, Mariano A J, Lumpkin R. 2017. An improved near-surface velocity climatology for the global ocean from drifter observations. Deep Sea Research Part I: Oceanographic Research Papers, 124: 73–92. doi: 10.1016/j.dsr.2017.04.009

|

| [20] |

Lee D K, Centurioni L R. 2013. The wintertime subtropical current in the Northwestern Pacific. Oceanography, 26(1): 28–37. doi: 10.5670/oceanog.2013.02

|

| [21] |

Li Li, Wu Boyu. 1989. A Kuroshio loop in South China Sea? —On circulations of the northeastern South China Sea. Journal of Oceanography in Taiwan Strait (in Chinese), 8(1): 89–95

|

| [22] |

Li Jiaxun, Zhang Ren, Jin Baogang. 2011. Eddy characteristics in the northern South China Sea as inferred from Lagrangian drifter data. Ocean Science, 7(5): 661–669. doi: 10.5194/os-7-661-2011

|

| [23] |

Liang W D, Yang Y J, Tang T Y, et al. 2008. Kuroshio in the Luzon Strait. Journal of Geophysical Research, 113(C8): C08048

|

| [24] |

Lien R C, Ma B, Cheng Y H, et al. 2014. Modulation of Kuroshio transport by mesoscale eddies at the Luzon Strait entrance. Journal of Geophysical Research, 119(4): 2129–2142

|

| [25] |

Liu Tongya, Xu Jiexin, He Yinghui, et al. 2016. Numerical simulation of the Kuroshio intrusion into the South China Sea by a passive tracer. Acta Oceanologica Sinica, 35(9): 1–12. doi: 10.1007/s13131-016-0930-x

|

| [26] |

Lu Jiuyou, Liu Qinyu. 2013. Gap-leaping Kuroshio and blocking westward-propagating Rossby wave and eddy in the Luzon Strait. Journal of Geophysical Research, 118(3): 1170–1181

|

| [27] |

Lumpkin R, Özgökmen T, Centurioni L. 2017. Advances in the application of surface drifters. Annual Review of Marine Science, 9: 59–81. doi: 10.1146/annurev-marine-010816-060641

|

| [28] |

Nan Feng, Xue Huijie, Chai Fei, et al. 2011a. Identification of different types of Kuroshio intrusion into the South China Sea. Ocean Dynamics, 61(9): 1291–1304. doi: 10.1007/s10236-011-0426-3

|

| [29] |

Nan Feng, Xue Huijie, Xiu Peng, et al. 2011b. Oceanic eddy formation and propagation southwest of Taiwan. Journal of Geophysical Research, 116(C12): C12045. doi: 10.1029/2011JC007386

|

| [30] |

Niiler P P, Maximenko N A, Panteleev G G, et al. 2003. Near-surface dynamical structure of the Kuroshio Extension. Journal of Geophysical Research, 108(C6): 3193. doi: 10.1029/2002JC001461

|

| [31] |

Niiler P P, Sybrandy A S, Bi K N, et al. 1995. Measurements of the water-following capability of holey-sock and TRISTAR drifters. Deep Sea Research Part I: Oceanographic Research Papers, 42(11–12): 1951–1955. doi: 10.1016/0967-0637(95)00076-3

|

| [32] |

Nitani H. 1972. Beginning of the Kuroshio. In: Stommel H, Yashida K, eds. Physical Aspects of the Japan Current. Seattle, USA: University of Washington Press, 129–163

|

| [33] |

Pazan S E, Niiler P P. 2001. Recovery of near-surface velocity from undrogued drifters. Journal of Atmospheric and Oceanic Technology, 18(3): 476–489. doi: 10.1175/1520-0426(2001)018<0476:RONSVF>2.0.CO;2

|

| [34] |

Peng Shiqiu, Qian Yukun, Lumpkin R, et al. 2015. Characteristics of the near-surface currents in the Indian Ocean as deduced from satellite-tracked surface drifters. Part I: Pseudo-Eulerian Statistics. Journal of Physical Oceanography, 45(2): 441–458. doi: 10.1175/JPO-D-14-0050.1

|

| [35] |

Qian Yukun, Peng Shiqiu, Li Yineng. 2013. Eulerian and Lagrangian statistics in the South China Sea as deduced from surface drifters. Journal of Physical Oceanography, 43(4): 726–743. doi: 10.1175/JPO-D-12-0170.1

|

| [36] |

Qiu Bo, Chen Shuiming. 2010. Interannual-to-decadal variability in the bifurcation of the north equatorial current off the Philippines. Journal of Physical Oceanography, 40(11): 2525–2538. doi: 10.1175/2010JPO4462.1

|

| [37] |

Qu Tangdong, Kim Y Y, Yaremchuk M, et al. 2004. Can Luzon Strait transport play a role in conveying the impact of ENSO to the South China Sea?. Journal of Climate, 17(18): 3644–3657. doi: 10.1175/1520-0442(2004)017<3644:CLSTPA>2.0.CO;2

|

| [38] |

Qu Tangdong, Mitsudera H, Yamagata T. 2000. Intrusion of the North Pacific waters into the South China Sea. Journal of Geophysical Research, 105(C3): 6415–6424. doi: 10.1029/1999JC900323

|

| [39] |

Ralph E A, Niiler P P. 1999. Wind-driven currents in the tropical Pacific. Journal of Physical Oceanography, 29(9): 2121–2129. doi: 10.1175/1520-0485(1999)029<2121:WDCITT>2.0.CO;2

|

| [40] |

Rudnick D L, Jan S, Centurioni L, et al. 2011. Seasonal and mesoscale variability of the Kuroshio near its origin. Oceanography, 24(4): 52–63. doi: 10.5670/oceanog.2011.94

|

| [41] |

Rypina I I, Jayne S R, Yoshida S, et al. 2014. Drifter-based estimate of the 5 year dispersal of Fukushima-derived radionuclides. Journal of Geophysical Research, 119(11): 8177–8193

|

| [42] |

Shaw P T. 1991. The seasonal variation of the intrusion of the Philippine sea water into the South China Sea. Journal of Geophysical Research, 96(C1): 821–827. doi: 10.1029/90JC02367

|

| [43] |

Sheu W J, Wu C R, Oey L Y. 2010. Blocking and westward passage of eddies in the Luzon strait. Deep Sea Research Part II: Topical Studies in Oceanography, 57(19-20): 1783–1791. doi: 10.1016/j.dsr2.2010.04.004

|

| [44] |

Sun Zhongbin, Zhang Zhiwei, Zhao Wei, et al. 2016. Interannual modulation of eddy kinetic energy in the northeastern South China Sea as revealed by an eddy-resolving OGCM. Journal of Geophysical Research, 121(5): 3190–3201

|

| [45] |

Tian Jiwei, Yang Qingxuan, Liang Xinfeng, et al. 2006. Observation of Luzon Strait transport. Geophysical Research Letters, 33(19): L19607. doi: 10.1029/2006GL026272

|

| [46] |

Trenberth K E, Large W G, Olson J G. 1989. The effective drag coefficient for evaluating wind stress over the oceans. Journal of Climate, 2(12): 1507–1516. doi: 10.1175/1520-0442(1989)002<1507:TEDCFE>2.0.CO;2

|

| [47] |

van Sebille E, Sprintall J, Schwarzkopf F U, et al. 2014. Pacific-to-Indian ocean connectivity: Tasman leakage, Indonesian Throughflow, and the role of ENSO. Journal of Geophysical Research, 119(2): 1365–1382

|

| [48] |

Wang Guihua, Wang Hui, Liu Zenghong, et al. 2008a. Observations of near surface current at the Luzon Strait in winter. Acta Oceanologica Sinica, 27(S1): 145–150

|

| [49] |

Wang Guihua, Wang Dongxiao, Zhou Tianjun. 2012. Upper layer circulation in the Luzon Strait. Aquatic Ecosystem Health & Management, 15(1): 39–45

|

| [50] |

Wang Dongxiao, Xu Hongzhou, Lin Jing, et al. 2008b. Anticyclonic eddies in the Northeastern South China Sea during Winter 2003/2004. Journal of Oceanography, 64(6): 925–935. doi: 10.1007/s10872-008-0076-3

|

| [51] |

Wu C R. 2013. Interannual modulation of the Pacific Decadal Oscillation (PDO) on the low-latitude western North Pacific. Progress in Oceanography, 110: 49–58. doi: 10.1016/j.pocean.2012.12.001

|

| [52] |

Yan Xiaomei, Zhu Xiaohua, Pang Chongguang, et al. 2016. Effects of mesoscale eddies on the volume transport and branch pattern of the Kuroshio east of Taiwan. Journal of Geophysical Research, 121(10): 7683–7700

|

| [53] |

Yu Kai, Qu Tangdong. 2013. Imprint of the Pacific Decadal Oscillation on the South China Sea throughflow variability. Journal of Climate, 26(24): 9797–9805. doi: 10.1175/JCLI-D-12-00785.1

|

| [54] |

Yuan Dongliang, Han Weiqing, Hu Dunxin. 2006. Surface Kuroshio path in the Luzon Strait area derived from satellite remote sensing data. Journal of Geophysical Research, 111(C11): C11007. doi: 10.1029/2005JC003412

|

| [55] |

Yuan Dongliang, Wang Zheng. 2011. Hysteresis and dynamics of a western boundary current flowing by a gap forced by impingement of mesoscale eddies. Journal of Physical Oceanography, 41(5): 878–888. doi: 10.1175/2010JPO4489.1

|

| [56] |

Zhang Zhiwei, Zhao Wei, Qiu Bo, et al. 2017. Anticyclonic eddy sheddings from Kuroshio loop and the accompanying cyclonic eddy in the northeastern South China Sea. Journal of Physical Oceanography, 47(6): 1243–1259. doi: 10.1175/JPO-D-16-0185.1

|

| [57] |

Zhang Zhiwei, Zhao Wei, Tian Jiwei, et al. 2015. Spatial structure and temporal variability of the zonal flow in the Luzon Strait. Journal of Geophysical Research, 120(2): 759–776

|

| [58] |

Zheng Quanan, Tai C K, Hu Jianyu, et al. 2011. Satellite altimeter observations of nonlinear Rossby eddy-Kuroshio interaction at the Luzon Strait. Journal of Oceanography, 67(4): 365–376. doi: 10.1007/s10872-011-0035-2

|

| 1. | Jintao Gu, Yu Zhang, Pengfei Tuo, et al. Surface floating objects moving from the Pearl River Estuary to Hainan Island: An observational and model study. Journal of Marine Systems, 2024, 241: 103917. doi:10.1016/j.jmarsys.2023.103917 | |

| 2. | Pedro Paulo de Freitas, Mauro Cirano, Carlos Eduardo Peres Teixeira, et al. Pathways of surface oceanic water intrusion into the Amazon Continental Shelf. Ocean Dynamics, 2024. doi:10.1007/s10236-024-01606-x | |

| 3. | Lingbo Cui, Mingyu Li, Tingting Zu, et al. Seasonality of Water Exchange in the Northern South China Sea from Hydrodynamic Perspective. Water, 2023, 16(1): 10. doi:10.3390/w16010010 | |

| 4. | Pengfei Tuo, Zhiyuan Hu, Shengli Chen, et al. Asymmetric Drifter Trajectories in an Anticyclonic Mesoscale Eddy. Remote Sensing, 2023, 15(15): 3806. doi:10.3390/rs15153806 | |

| 5. | Zhenyu Sun, Jianyu Hu, Hongyang Lin, et al. Lagrangian Observation of the Kuroshio Current by Surface Drifters in 2019. Journal of Marine Science and Engineering, 2022, 10(8): 1027. doi:10.3390/jmse10081027 |