| Citation: | Joanna W. Doinsing, Vienna Anastasia Admodisastro, Laditah Duisan, Julian Ransangan. Population dynamics and condition index of natural stock of blood cockle, Tegillarca granosa (Mollusca, Bivalvia, Arcidae) in the Marudu Bay, Malaysia[J]. Acta Oceanologica Sinica, 2021, 40(8): 89-97. doi: 10.1007/s13131-021-1791-5 |

Blood cockle, Tegillarca granosa (Linnaeus, 1758), formerly known as Anadara granosa is a bivalvia under the Arcidae family. It inhabits soft muddy bottoms of tidal flats formed in estuaries or interior of bays (Nakao et al., 1989) and known to be widely distributed from the Middle East to East Asia (Faulkner, 2010). In Malaysia, T. granosa is naturally found in Penang, Perak, Selangor (Pathansali and Song, 1958) and Johor (Yurimoto et al., 2014). Moreover, according to Hamli et al. (2012), the bivalve is also found in Sarawak particularly in Kuching and Bintulu regions.

T. granosa is a major fishery in the Malaysia’s inshore waters, contributing over 50% to national aquaculture production (Sugiyama et al., 2004) and dominating 93% of total shellfish species production (Department of Fisheries Malaysia, 2013). In 2002, Malaysia was ranked 5th in Asia Pacific in the production of T. granosa with 78 712 tons (Sugiyama et al., 2004). Since the first commercial exploitation in Perak in 1948, this species has been cultivated extensively on several mudflats on Malaysia’s west coast such as Kedah (Merbok), Pulau Pinang (Juru), Perak (Kuala Gula, Kuala Sangga-Matang, Kuala Trong, Sg.Jarum), Selangor (Kuala Selangor) and Johor (Muar) (Mirzaei et al., 2015). There is no direct evidence in the literature on the distribution of T. granosa in Sabah. However, based on our observation, this species occurs in three areas namely Marudu Bay (North Eastern Sabah), Labuk Bay and Tawau (Eastern Sabah) in Sabah. Moreover, our observation also indicated that fewer cockles are being caught by fishers every year. This situation is alarming as the cockle resource in the bay may not be able to sustain unless an intervention is carried out to sustainably manage its natural stock.

Population parameter assessments are important for an effective management of the fishery. A number of similar studies on population dynamics of this species have been conducted in Kuala Juru, Kuala Sepetang, Sungai Besar Selangor (Oon, 1986), Sungai Buloh (Broom, 1982), and Balik Pulau (Mirzaei et al., 2015) in Malaysia as well as in other countries in Kakinada Bay, India (Narasimham, 1988b), Ang Sila, Thailand (Vakily, 1992), and Desa Menco, Kecamatan Wedung dan Demak in Indonesia (Imtihan et al., 2014). Despite the extensive literature of this topic, information on the occurrence and the distribution of this species in Northeast Malaysian Borneo (Sabah) is still scarce. Therefore, this study is established to acquire baseline information regarding the population dynamics and the level of exploitation on the natural stock of this species in the Marudu Bay.

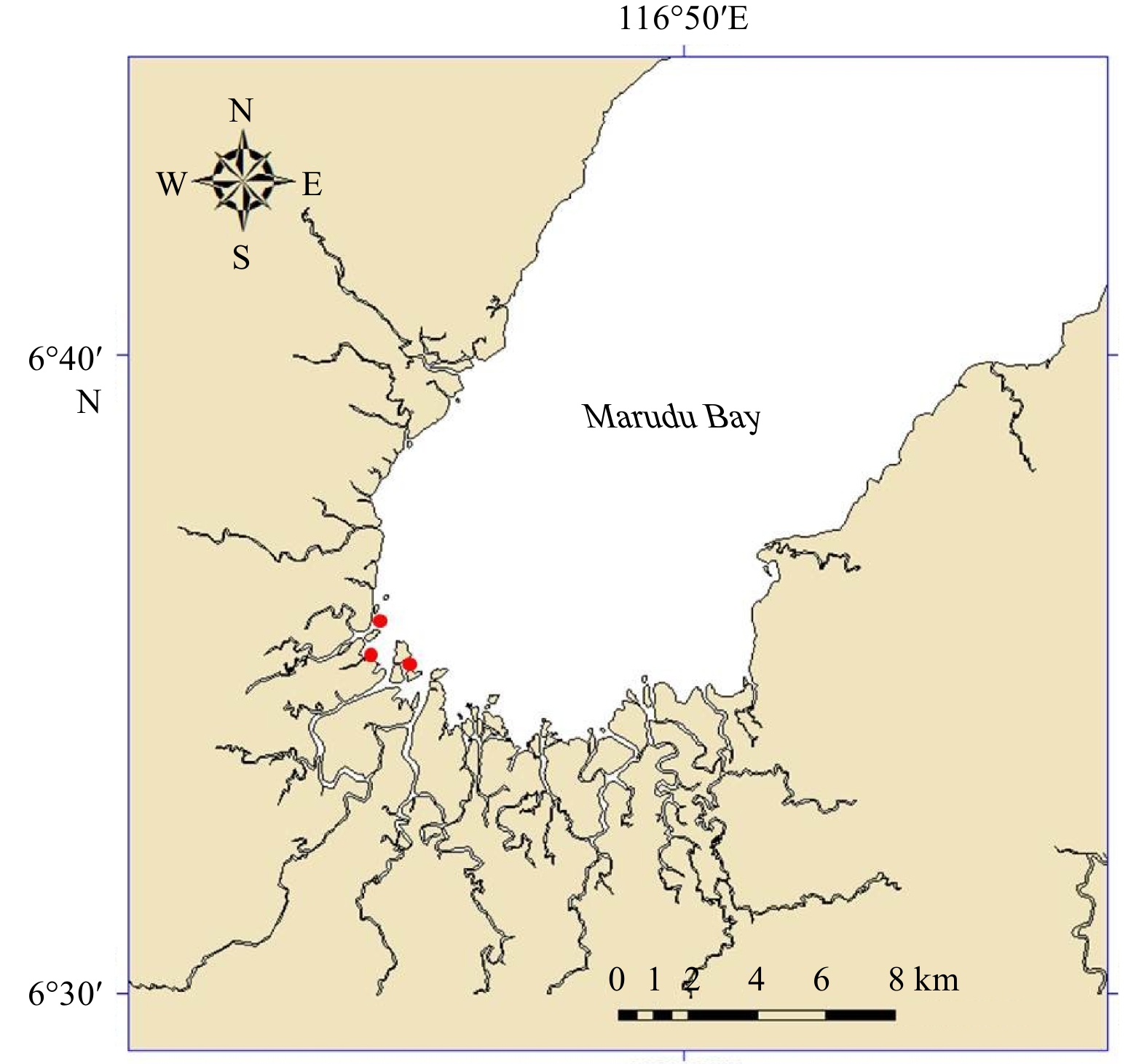

Marudu Bay (6°35′–7°00′N, 116°45′–117°00′E) is situated within the Tun Mustapha Marine Park (Fig. 1), the largest marine protected area on the northeast Borneo. Monthly samplings were conducted from July 2017 to June 2018. Samples of T. granosa (Fig. 2) in an area of 500 m2 (50 m×10 m) were hand collected. A total of 279 specimens were obtained throughout the study period (Table 1). Shell length (anterior-posterior) of each specimen was measured with accuracy of 0.1 mm using Vernier calipers (Mitutoyo, Shah Alam, Malaysia). The total weight was recorded using an electronic balance to the nearest 0.01 g.

| Midlength/mm | Jul. 2017 | Aug. 2017 | Sept. 2017 | Oct. 2017 | Nov. 2017 | Dec. 2017 | Jan. 2018 | Feb. 2018 | Mar. 2018 | Apr. 2018 | May 2018 | Jun. 2018 |

| 27.5 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 32.5 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 37.5 | 3 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 42.5 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 47.5 | 4 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 7 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| 52.5 | 27 | 8 | 1 | 4 | 5 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 1 | 4 |

| 57.5 | 9 | 1 | 3 | 5 | 8 | 0 | 4 | 7 | 7 | 5 | 3 | 9 |

| 62.5 | 5 | 6 | 4 | 3 | 5 | 4 | 2 | 8 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 9 |

| 67.5 | 2 | 4 | 5 | 1 | 9 | 2 | 1 | 4 | 3 | 0 | 2 | 3 |

| 72.5 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 7 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 77.5 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 82.5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Total | 55 | 20 | 20 | 14 | 45 | 13 | 14 | 26 | 19 | 13 | 11 | 29 |

| Note: 0 represents no cockle found. | ||||||||||||

The monthly 5 mm intervals of shell length frequency distribution data of cockle specimens were used to estimate the growth parameters (L∞, K, ϕ), mortality (Z, M, F), exploitation (E) and recruitment of the species in the Marudu Bay using the FAO-ICLARM Stock Assessment Tools (FiSAT) computer package (Gayanilo et al., 2005).

Five random specimens of blood cockles were collected each month and were used for condition index (CI) analysis during the experimental period (12 months). Briefly, the cockle specimens were dissected to separate meat from the shell. Then, the meats and the empty shells were completely dried in drying oven (Memmert, Büchenbach, Germany). The condition index was then calculated based on the ratio of the dry meat weight (DW) and the shell weight (SW) following Davenport and Chen (1987) as follows:

| $$ {\rm{CI }}\! \!=\!\! {\rm{ }}\left({{\rm{DW}}/{\rm{SW}}} \right){\rm{ }}\!\! \times\!\! {\rm{ }}100. $$ | (1) |

The monthly condition indices were analysed using the SPSS Windows Statistical Package (version 21, Chicago, IL, USA). The tests were judged to be significant at p<0.05 level. Prior to analyses, all variables were tested for normality and homogeneity of variances.

The relationship of W = aLb, where W is the weight (g) and L is the length (mm) of T. granosa, a is the intercept (condition factor) and b is the slope (growth coefficient) was used to establish the length-weight relationship (Quinn II and Deriso, 1999). The a and b parameters were calculated using regression analysis of log-log transformed data:

| $$ {\rm{log}}_{10}W = {\rm{ log}}_{10}a + b{\rm{log}}_{10}L. $$ | (2) |

The correlation (R2), which is the level of relationship between the length and weight, was calculated from the linear analysis. If b = 3.0, growth is isometric, however if b>3.0, growth is positive allometric. Growth is negative allometric when b<3.0.

The asymptotic length (L∞) and the growth coefficient (K) of the von Bertalanffy growth function (VBGF) of the cockle stock were estimated by means of ELEFAN 1 (Pauly and David, 1981). The inverse von Bertalanffy growth equation (Sparre and Venema, 1992) was used to estimate the average length of the cockle at certain age by the equation:

| $$ {L}_{t}={L}_{\infty }\left[1-{{\rm{e}}}^{-K\left(t-{t}_{0}\right)}\right]{\rm{,}} $$ | (3) |

where Lt is the mean length at age t and t0 is the hypothetical age at which the length is zero (Newman, 2002). The t0 value was predicted by using Pauly (1983) equation as follows:

| $$ \mathrm{log}_{10}\left(-{t}_{0}\right)=-0.392\;2-0.275\;2{\mathrm{log}}_{10}{L}_{\infty }-1.038{\mathrm{log}}_{10}K. $$ | (4) |

The potential longevity (tmax) of the cockles was procured using the Pauly (1983) formula tmax=3/K. The growth performance index (ϕ) was then estimated by using the estimated L∞ and K values (Pauly and Munro, 1984) based on the following equation:

| $$ \phi = {\rm{ }}2{\rm{lo}}{{\rm{g}}_{10}}{L_\infty } + {\rm{ lo}}{{\rm{g}}_{10}}K. $$ | (5) |

The recruitment rates were obtained by backward projection on the length axis of a set of available length-frequency data as described in FiSAT routine (Pauly and David, 1981).

Total mortality (Z) is comprised of two components: natural mortality (M); mortality due to predation, disease, etc., and fishing mortality (F); mortality due to harvesting by humans. The total mortality (Z) was estimated by the length converted catch curve method (Pauly and Munro, 1984) and fishing mortality (F) was estimated by the following equation:

| $$ F = Z - M. $$ | (6) |

The exploitation level (E) was then estimated based on the equation described by Gulland (1965) as follows:

| $$ E=F/\left(F+M\right). $$ | (7) |

Relative yield per recruit (Y'/R) and biomass per recruit (B'/R) were estimated according to the model of Beverton and Holt (1993) using the knife-edge selection.

The condition indices of the blood cockle (T. granosa) in the Marudu Bay ranged from 3.05 to 7.17 with a mean (±SD) of 4.98±0.86 (Fig. 3). The maximum values occurred in July followed by a steady decline in October and further decrease to the minimum levels in February. However, no significant difference (p>0.05) was observed in condition indices throughout the study period.

The length and weight of T. granosa ranged 27.7–82.2 mm and 13.11–192.7 g, respectively. The calculated length-weight relationship equation was log10W=2.681 7log10L − 0.17816, R2=0.9501. The exponential form of the equation was W=0.6635L2.6817 (R2=0.9501) which was found by plotting the length values against weight (Fig. 4). The computed growth coefficient (b) was 2.6 at 95% confidence limit.

The growth parameters (L∞, K, t0) are useful in assessing the growth rates between and within individuals inhabiting various environments. The estimated asymptotic length (L∞) of the T. granosa was 86.68 mm and the growth coefficient (K) was 0.98 a–1. The estimated t0 was −0.1212 for T. granosa in the Marudu Bay. The computer growth curve using these parameters is shown over the restructured length distribution based on the length-frequency data (Fig. 5).

The observed maximum shell length of T. granosa in the Marudu Bay was 82.55 mm and the predicted maximum shell length was 84.44 mm (Fig. 6). The confidence interval was 79.29 mm to 89.58 mm (95% probability of occurrence). The mean lengths of T. granosa in the Marudu Bay were estimated to be 21.31 mm, 31.16 mm, 39.53 mm, 46.63 mm, 52.67 mm and 57.79 mm at the end of 2, 4, 6, 8, 10 and 12 months of age, respectively. The best estimated value of K was 0.98 a–1 (Fig. 7) and the growth performance index (ϕ) was 3.87. The estimated maximum life span (tmax) was 3.06 years, which showed that T. granosa is a short-lived species.

The recruitment of T. granosa in the Marudu Bay occurred throughout the year with two apparent peaks, one is in March and another is in October (Fig. 8). The percent recruitment varied from 1.2% to 19.75% during the 1-year study. The highest and lowest percent recruitment was observed in October and August. More than 38% of the total recruitment was contributed by the spawning peaks in March and October.

The total mortality of the blood cockle in the Marudu Bay was estimated at 2.39 a–1. The mean annual seawater temperature (28.4°C) was used to calculate the natural mortality in study site. Natural events and fishing activities were estimated to contribute the mortality at the rate of 1.32 a–1 and 1.07 a–1, respectively (Fig. 9). Meanwhile, the estimated exploitation level (E) of the cockle in Marudu Bay was at 0.45. Figure 10 shows the results of the relative Y'/R and B'/R analysis for T. granosa using two types of selection curves. The computed maximum allowable limit of exploitation (Emax) for the Y'/R and B'/R was 0.395.

Condition index (CI) is often used to characterize flesh quality or the apparent condition of a stock under a given environmental condition (Li et al., 2009). The values of condition index can be generally divided into three fatness categories (CI≤2 (thin); CI=2 to 4 (moderate); CI≥4 (fat)) (Davenport and Chen, 1987). In the present study it was noted that the condition index of the blood cockles in the Marudu Bay was estimated at 4.98±0.86 which fell within the fat category. This value was higher than that of the same species recorded in the Kakinada Bay, India (Narasimham, 1988a) (Table 2) but much lower than those occurred in the Straits of Malacca, Malaysia (Khalil et al., 2017) and Black Sea Coast, Turkey (Sahin et al., 2006).

| Location | Species | Condition index (±SD) | Reference |

| Marudu Bay, Malaysia | Tegillarca granosa | 4.98±0.86 | current study |

| Straits of Malacca, Malaysia | Anadara granosa | 6.76±1.13 | Khalil et al. (2017) |

| Black Sea Coast, Turkey | A. granosa | 7.88±1.80 | Sahin et al. (2006) |

| Kakinada Bay, India | A. granosa | 4.11 | Narasimham (1988a) |

The influence of environmental conditions such as temperature (Freites et al., 2010; Khalil, 2013), salinity (Engle, 1958), seasonal variations (Rebelo et al., 2005; Sahin et al., 2006), chemical property of the water and the sediment (Engle, 1958), population density, availability of food (Korringa, 1952; Galtsoff, 1965) and different pollutants have on bivalves can be evaluated using the CI (Lawrence and Scott, 1982; Scott and Lawrence, 1982; Rosas et al., 1983; Marcus et al., 1989). The CI can be used as a tool to determine the ecophysiological influences that affect the physiological changes which suffered by the bivalves in the forms of carbohydrate, glycogen and protein fractions, and also lipid and mineral contents (Mercado-Silva, 2005). In the previous studies, the correlations between CI and phytoplankton biomass were shown apparent in Anadara inaequivalvis (Sahin et al., 2006), Laternula elliptica (Kang et al., 2009) and Fulvia fragilis (Rifi et al., 2015). Besides, previous studies also showed correlation between CI and sea temperature in Cerastoderma edule (Ong et al., 2017) and F. fragilis (Rifi et al., 2015).

Based on the estimation from the length-weight relationship, the growth coefficient b generally lies between 2.5 and 3.5. The growth coefficient b is a shape parameter to determine the body form of the species (Kuriakose, 2017). The relation is said to be isometric when it is equal to 3 (Carlander, 1997). In isometric growth, every part of the organism’s body grows at the same rate while in allometric growth the proportions of organism’s body parts grow at different rate manner in which the length was growing faster than the weight. The growth coefficient b value (2.6) in the current study was smaller than the isometric value (b=3). Therefore, the value of b in the current study demonstrates that T. granosa grows negative allometrically (length was growing faster than the weight) instead of isometrically.

In addition, b value of the current study (2.6) was higher than those reported in the Balik Pulau, Malaysia (2.33) (Mirzaei et al., 2015) and Kakinada Bay, India (2.12) (Narasimham, 1988b) but lower than those reported in the Phuket, Thailand (3.04) (Boonruang and Janekarn, 1983) and Sungai Buloh, Malaysia (3.37) (Broom, 1982) (Table 3). The different values may be due to the influence of biological and ecological factors such as the availability of food (Fréchette et al., 1992; Nakaoka, 1992), water temperature, density and shore level (Hickman, 1979).

| Location | Species | a | b | Reference |

| Marudu Bay, Malaysia | Tegillarca granosa | 0.664 | 2.60 | current study |

| Balik Pulau, Malaysia | Anadara granosa | 0.002 | 2.33 | Mirzaei et al. (2015) |

| Sungai Buloh, Malaysia | A. granosa | 0.240 | 3.37 | Broom (1982) |

| Kakinada Bay, India | A. granosa | 0.260 | 2.12 | Narasimham (1988b) |

| Thailand | A. granosa | 0.360 | 3.04 | Boonruang and Janekarn (1983) |

| Note: a is the intercept (condition factor) and b is the slope (growth coefficient). | ||||

The asymptotic length (L∞) of T. granosa in the Marudu Bay (86.68 mm) was higher compared to species occurring in other places: Malaysia (35.4 mm to 45 mm) (Mirzaei et al., 2015; Broom, 1982; Oon, 1986), India (73.4 mm) (Narasimham, 1988b) and Thailand (36.9 mm) (Vakily, 1992) but lower than the one reported in the Indonesia (106.8 mm to 129.9 mm) (Imtihan et al., 2014) (Table 4). The growth coefficient value, K for the cockles in the Marudu Bay (0.98 a–1) which describes how quickly the maximum length is attained was higher than those recorded in other places (0.06 a–1 to 0.88 a–1) with exception to Balik Pulau, Malaysia (1.1 a–1) (Mirzaei et al., 2015), Sungai Buloh, Malaysia (1.01 a–1) (Broom, 1982) and Ang Sila, Thailand (1.86 a–1) (Vakily, 1992).

| Location | Species | L∞/mm | K/a–1 | F/a–1 | E | Reference |

| Marudu Bay, Malaysia | Tegillarca granosa | 86.68 | 0.98 | 1.07 | 0.45 | current study |

| Balik Pulau, Malaysia | Anadara granosa | 35.4 | 1.1 | 0.48 | 0.16 | Mirzaei et al.(2015) |

| Kuala Juru, Malaysia | A. granosa | 45 | 0.55 | 2.69 | 0.83 | Oon (1986) |

| Kuala Sepetang, Malaysia | A. granosa | 40.5 | 0.79 | 3.33 | 0.81 | Oon (1986) |

| Sungai Besar Selangor, Malaysia | A. granosa | 41.4 | 0.78 | 2.88 | 0.79 | Oon (1986) |

| Pulau Sangga, Malaysia | A. granosa | 37.2 | 0.88 | 2.05 | 0.7 | Oon (1986) |

| Sungai Buloh, Malaysia | A. granosa | 44.4 | 1.01 | – | – | Broom (1982) |

| Kakinada Bay, India | A. granosa | 73.4 | 0.58 | – | – | Narasimham (1988b) |

| Ang Sila, Thailand | A. granosa | 36.9 | 1.86 | – | – | Vakily (1992) |

| Desa Menco, Indonesia | A. granosa | 129.9 | 0.07 | – | – | Imtihan et al. (2014) |

| Kecamatan Wedung, Indonesia | A. granosa | 112.1 | 0.07 | – | – | Imtihan et al. (2014) |

| Demak, Indonesia | A. granosa | 106.8 | 0.06 | – | – | Imtihan et al. (2014) |

| Note: L∞: estimated asymptotic length; K: growth coefficient; F: estimated fishing mortality; E: estimated exploitation level. | ||||||

Environmental conditions and population crowding have known to negatively influence the growth of blood cockles (Broom, 1985; Tiensongrusmee and Pontjoprawiro, 1988). Substrate, salinity, dissolved oxygen, slope of the muddy flat where the cockles are seeded and the food availability are among the main environmental factors known to affect the growth of blood cockles (Broom, 1985; Gosling, 2003). The productivity and the growth rate of mollusc species can be restricted by extreme differences in salinity, increase exposure period of the muddy flat, and population density of cockles (Broom, 1985, Davenport and Wong, 1986).

The estimated maximum life span (tmax) was 3.06 years, for the blood cockle T. granosa in the Marudu Bay, Sabah. The present findings seem to be consistent with Mirzaei et al. (2015) in the Balik Pulau, Penang Island (2.72 years) and Narasimham (1969) in the Kakinada Bay, India (3 years) which showed that T. granosa is a short-lived species.

The current study demonstrated that the recruitment of T. granosa in the Marudu Bay occurs all year round, with two seasonal pulse producing two cohorts per year (March and October) and the highest peak occurs in October. This finding is in agreement with major spawning season reported from previous research (Table 5) and is backed up by the evidence in Khalil et al. (2017) through which the author reported that Anadara granosa spawn in February to March and October in the Pulau Pinang, Malaysia, September to October in the Banda Aceh and Lhokseumawe, Indonesia. Further studies using environmental variables are recommended to explain spawning and recruitment patterns.

| Location | Species | Spawning period | Reference |

| Marudu bay, Malaysia | Tegillarca granosa | March to April and September to October | current study |

| Pulau Pinang, Malaysia | Anadara granosa | February to March and October | Khalil et al. (2017) |

| Pulau Pinang, Malaysia | A. granosa | August to September | Broom (1983) |

| Selangor, Malaysia | A. granosa | September and November | Broom (1983) |

| Phuket, Thailand | A. granosa | October to November | Boonruang and Janekarn (1983) |

| Pattani Bay, Thailand | A. granosa | September and December | Suwanjarat et al. (2009) |

| Banda Aceh, Indonesia | A. granosa | September to October | Khalil et al. (2017) |

| Lhokseumawe, Indonesia | A. granosa | September to October | Khalil et al. (2017) |

Mortality and exploitation level are important parameters to understand the dynamic population of cockles (Mirzaei et al., 2015). Recommended exploitation rate of 0.5 has been suggested by Gulland (1984) as a sustainable exploitation, where the fishing mortality is equal to natural mortality. In the current study, the higher natural mortality (M=1.32 a–1) compared to the fishing mortality (F=1.07 a–1) rate indicated the unbalance position of the stock. The exploitation rate of 0.45 which is below the recommended exploitation rate of 0.5 suggesting that natural events were the major cause of death among cockles in the Marudu Bay.

However, the estimated maximum allowable limit of exploitation rate (Emax) giving maximum relative Y'/R was 0.395, which was very well below the actual exploitation rates of 0.45. Thus, the cockle stock in the Marudu Bay appears to be overexploited in terms of Y'/R and B'/R. This is confirmed by the local’s scarcity observation of cockles at the areas close to the villages and that the fishers tended to explore areas far from the common fishing grounds to get a good catch.

The result of the current study was in accordance with the findings of other studies conducted in Malaysia such as Kuala Juru, Kuala Sepetang, Sangga Besar and Sungai Buloh (0.7 to 0.83) (Oon, 1986), where the exploitation rates of T. granosa were above the recommended sustainable exploitation rate of 0.5. These high exploitation levels could have been attributed to the high market demand of T. granosa in the Peninsular Malaysia (Mirzaei et al., 2015). Through this analysis, the need of decreasing fishing effort corresponding fishing mortality has been made evident. An alternative to this is to carry out a sustainable fishery management.

These scientific information on population dynamics and condition index of cockle derived from the current study can be utilized for establishing sustainable fishery management strategies for natural stocks of blood cockle in the Marudu Bay. Dynamic population models can be designed to provide management authorities an indication of the bay’s carrying capacity (Dame, 1993) as the aim of a sustainable fishery management is the estimation of the area’s carrying capacity (National Research Council, 2010). Carrying capacity can be described in terms of a system’s physical environment, output yield and ecological condition, as well as local social and cultural structures tolerance (National Research Council, 2010). Estimating the capacity carrying system has focused largely on determining the carrying capacity output, which is the maximum sustainable yield that can be produced within a region (McKindsey et al., 2006). By understanding the maximum sustainable yield, it will help to determine how much resources can be harvested from sea without further depletion.

Besides, strategies such as size restriction for harvesting, close season for fishing, restricted fishing zone and use of non-destructive fishing gear can also be implemented in carrying out sustainable fishery management. However, these management strategies should take into consideration the economic aspects of fishermen communities as the farmers are more concerned with short-term economic benefits or meeting the demands of their daily needs (Santoso et al., 2015). This fact can be supported by the past event whereby the involvement of government to stabilize the industry and to prevent overexploitation of the cockle population was met with much resistance from the cockle farmers. The dropped production of cockles from an all-time high of 120 000 tonnes in 1980 to 40 000 tonnes in 1983 and the increased of spats’ prices to more than double from 1919 to 1980 had caused the government to enforce minimum catch size of 31.8 mm and a ban on the exports of spats. However, the implementation of the minimum catch size of 31.8 mm has experienced much objections from the cockle farmers since they considered the size is too large for feasible culture operations (Oon, 1986).

Therefore, more viable management strategy is suggested by practising cohesive interaction in responsible blood cockle fisheries management. In this interaction, local farmers’ participation in management is incorporated in creating sustainable livelihoods and promoting integrated management towards sustainable fisheries (De Young et al., 2008). The local farmers will be able to earn income by collecting blood cockles and selling them to markets in terms of livelihood sustainability while practicing sea ranching strategy by rearing juveniles’ blood cockle caught and allowing blood cockle to breed in the wild before marketed. This sea ranching strategy is helpful in developing aquaculture for replenishing cockle stocks and at the same time allowing farmers to gain both caught and aquaculture productions for economic benefits (Santoso et al., 2015). Besides, it is also important to practice integrated management approach by conserving the mangrove forests and conducting surveillance on the irresponsible fishing practiced in the area to ensure the sustainability of this blood cockle fisheries (Suanrattanachai et al., 2011).

The current study demonstrated T. granosa population in the Marudu Bay grew in negative allometric fashion. However, it has a satisfactory condition index and recruitment. Although it reproduces continuously throughout the year, the exploitation level was approaching the maximum exploitation level that if it is not managed sustainably, it could lead to population collapse. Hence, fishing the natural stock of the cockle in the Marudu Bay requires sustainable management plan by involving local farmers in practicing integrated management approach such as sea ranching program, conservation of mangrove forests and surveillance on irresponsible fishing.

| [1] |

Beverton R J H, Holt S J. 1993. On the Dynamics of Exploited Fish Populations. Dordrecht, the Netherlands: Springer

|

| [2] |

Boonruang P, Janekarn V. 1983. Distribution, density, biomass and population bionomics of Anadara granosa (L.) in relation to environmental factors at Sapum Bay on the east coast of Phuket Island. Thai Fisheries Gazette, 36: 461–468

|

| [3] |

Broom M J. 1982. Analysis of the growth of Anadara granosa (Bivalvia: Arcidae) in natural, artificially seeded and experimental populations. Marine Ecology Progress Series, 9: 69–79. doi: 10.3354/meps009069

|

| [4] |

Broom M J. 1983. Mortality and production in natural, artificially-seeded and experimental populations of Anadara granosa (Bivalvia: Arcidae). Oecologia, 58(3): 389–397. doi: 10.1007/BF00385241

|

| [5] |

Broom M J. 1985. The biology and culture of marine bivalve molluscs of the genus Anadara. ICLARM Studies and Reviews, 12: 1–37

|

| [6] |

Carlander K D. 1997. Handbook of Freshwater Fishery Biology. Ames, IA, USA: Iowa State University Press

|

| [7] |

Dame R F. 1993. Bivalve Filter Feeders in Estuarine and Coastal Ecosystem Processes. Berlin Heidelberg, Germany: Springer, 455–476

|

| [8] |

Davenport J, Chen Xiaogang. 1987. A comparison of methods for the assessment of condition in the mussel (Mytilus edulis L.). Journal of Molluscan Studies, 53: 293–297. doi: 10.1093/mollus/53.3.293

|

| [9] |

Davenport J, Wong T M. 1986. Responses of the blood cockle Anadara granosa (L.) (Bivalvia: Arcidae) to salinity, hypoxia and aerial exposure. Aquaculture, 56: 151–162. doi: 10.1016/0044-8486(86)90024-4

|

| [10] |

De Young C, Charles A, Hjort A. 2008. Human dimensions of the ecosystem approach to fisheries: an overview of context, concepts, tools and methods. Rome, Italy: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, 3–9

|

| [11] |

Department of Fisheries Malaysia. 2013. Perangkaan Tahunan Perikanan 2013. https://www.dof.gov.my/index.php/pages/view/82 [2020−1−21]

|

| [12] |

Engle J B. 1958. The seasonal significance of total solids of oysters in commercial exploitation. Proceedings National Shellfisheries Association, 48: 72–78

|

| [13] |

Faulkner P. 2010. Morphometric and taphonomic analysis of granular ark (Anadara granosa) dominated shell deposits of Blue Mud Bay, northern Australia. Journal of Archaeological Science, 37(8): 1942–1952. doi: 10.1016/j.jas.2010.02.021

|

| [14] |

Fréchette M, Aitken A E, Pagé L. 1992. Interdependence of food and space limitation of a benthic suspension feeder: consequences for self-thinning relationships. Marine Ecology Progress Series, 83: 55–62. doi: 10.3354/meps083055

|

| [15] |

Freites L, Montero L, Arrieche D, et al. 2010. Influence of environmental factors on the reproductive cycle of the eared ark Anadara notabilis (Röding, 1798) in northeastern Venezuela. Journal of Shellfish Research, 29(1): 69–75. doi: 10.2983/035.029.0128

|

| [16] |

Galtsoff P S. 1965. The American oyster, Crassostrea virginica Gmelin. Washington, DC, USA: Fish and Wildlife Services, 480

|

| [17] |

Gayanilo F, Sparre P, Pauly D. 2005. FAO-ICLARM stock assessment tool (FiSAT) user’s manual, Reference Manual. FAO Computerized Information Series (Fisheries) No. 8, Revised Version. Rome, Italy: Food and Agriculture Organization, 168

|

| [18] |

Gosling E. 2003. Bivalve Molluscs: Biology, Ecology and Culture. Oxford, UK: Blackwell Publishing, 6

|

| [19] |

Gulland J A. 1965. Survival of the youngest stages of fish, and its relation to year-class strength. Special Publication (International Commission for the Northwest Atlantic Fisheries), 6: 365–371

|

| [20] |

Gulland J A. 1984. Advice on target fishing rates. Fishbyte, The WorldFish Center, 2(1): 8–11

|

| [21] |

Hamli H, Idris M H, Abu Hena M K, et al. 2012. Taxonomic study of edible bivalve from selected division of Sarawak, Malaysia. International Journal of Zoological Research, 8(1): 52–58. doi: 10.3923/ijzr.2012.52.58

|

| [22] |

Hickman R W. 1979. Allometry and growth of the green-lipped mussel Perna canaliculus in New Zealand. Marine Biology, 51(4): 311–327. doi: 10.1007/BF00389210

|

| [23] |

Imtihan R R, Hartati R, Suprijanto J. 2014. Biometrika kerang darah (Anadara granosa) pada tambak budidaya di Desa Menco Kecamatan Wedung Kabupaten Demak. Journal of Marine Research, 3(4): 642–649

|

| [24] |

Kang D H, Ahn I Y, Choi K S. 2009. The annual reproductive pattern of the Antarctic clam, Laternula elliptica from Marian Cove, King George Island. Polar Biology, 32: 517–528. doi: 10.1007/s00300-008-0544-7

|

| [25] |

Khalil M. 2013. The effect of environmental condition on the spawning period of blood cockle Anadara granosa (Bivalvia: Archidae) in Lhokseumawe, The Northern Straits of Malacca. Jurnal Agrium, 10(2): 69–76

|

| [26] |

Khalil M, Yasin Z, Hwai T S. 2017. Reproductive biology of blood cockle Anadara granosa (Bivalvia: Arcidae) in the northern region of the Strait of Malacca. Ocean Science Journal, 52(1): 75–89. doi: 10.1007/s12601-017-0010-y

|

| [27] |

Korringa P. 1952. Recent advances in oyster biology. The Quarterly Review of Biology, 27(3): 266–308. doi: 10.1086/399023

|

| [28] |

Kuriakose S. 2017. Estimation of length weight relationship in fishes. In: Course Manual Series No. 2/2017. Kochi, India: Central Marine Fisheries Research Institute, 215–220

|

| [29] |

Lawrence D R, Scott G I. 1982. The determination and use of condition index of oysters. Estuaries, 5(1): 23–27. doi: 10.2307/1352213

|

| [30] |

Li Yan, Qin J G, Li Xiaoxu, et al. 2009. Monthly variation of condition index, energy reserves and antibacterial activity in Pacific oysters, Crassostrea gigas, in Stansbury (South Australia). Aquaculture, 286(1–2): 64–71. doi: 10.1016/j.aquaculture.2008.09.004

|

| [31] |

Linnaeus C. 1758. Systema naturae per regna tria naturae, 10th edn. vol. 1. Regnum Animale. Stockholm, Sweden: Laurentii Salvii

|

| [32] |

Marcus J M, Scott G I, Heizer D D. 1989. The use of oyster shell thickness and condition index measurements as physiological indicators of no heavy metal pollution around three coastal marinas. Journal of Shellfish Research, 8(1): 87–94

|

| [33] |

McKindsey C W, Thetmeyer H, Landry T, et al. 2006. Review of recent carrying capacity models for bivalve culture and recommendations for research and management. Aquaculture, 261(2): 451–462. doi: 10.1016/j.aquaculture.2006.06.044

|

| [34] |

Mercado-Silva N. 2005. Condition index of the eastern oyster, Crassostrea virginica (Gmelin, 1791) in Sapelo Island Georgia-effects of site, position on bed and pea crab parasitism. Journal of Shellfish Research, 24(1): 121–126. doi: 10.2983/0730-8000(2005)24[121:CIOTEO]2.0.CO;2

|

| [35] |

Mirzaei M R, Yasin Z, Hwai A T S. 2015. Length-weight relationship, growth and mortality of Anadara granosa in Penang Island, Malaysia: an approach using length-frequency data sets. Journal of the Marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom, 95(2): 381–390. doi: 10.1017/S0025315414001337

|

| [36] |

Nakao S, Nomura H, Satar M K B A. 1989. Macrobenthos and sedimentary environments in a Malaysian intertidal mudflat of the cockle bed. Bulletin of the Faculty of Fisheries Hokkaido University, 40(4): 203–213

|

| [37] |

Nakaoka M. 1992. Spatial and seasonal variation in growth rate and secondary production of Yoldia notabilis in Otsuchi Bay, Japan, with reference to the influence of food supply from the water column. Marine Ecology Progress Series, 88: 215–223. doi: 10.3354/meps088215

|

| [38] |

Narasimham K A. 1969. Studies on some aspects of biology and fishery of the cockle, Anadara granosa (Linnaeus), from Kakinada Bay. In: Proceedings of the Symposium on Mollusca. Cochin, India: Marine Biology Association of India, 407–417

|

| [39] |

Narasimham K A. 1988a. Biology of the blood clam Anadara granosa (Linnaeus) in Kakinada bay. Journal of the Marine Biological Association of India, 30(1–2): 137–150

|

| [40] |

Narasimham K A. 1988b. Taxonomy of the blood clams Anadara (Tegillarca) granosa (Linnaeus, 1758) and A. (T.) Rhombea (Born, 1780). Journal of the Marine Biological Association of India, 30(1–2): 200–205

|

| [41] |

National Research Council. 2010. Ecosystem Concepts for Sustainable Bivalve Mariculture. Washington, DC, USA: National Academies Press, 87–106

|

| [42] |

Newman S J. 2002. Growth, age estimation and preliminary estimates of longevity and mortality in the Moses perch, Lutjanus russelli (Indian Ocean form), from continental shelf waters off north-western Australia. Asian Fisheries Science, 15: 283–294

|

| [43] |

Ong E Z, Briffa M, Moens T, et al. 2017. Physiological responses to ocean acidification and warming synergistically reduce condition of the common cockle Cerastoderma edule. Marine Environmental Research, 130: 38–47. doi: 10.1016/j.marenvres.2017.07.001

|

| [44] |

Oon N F. 1986. Growth and mortality of the Malaysian cockle (Anadara granosa L.) under commercial culture: Analysis through length-frequency data. Bay of Bengal Programme: Development of Small-Scale Fisheries Working Paper BOBP/WP/47. Madras: Bay of Bengal Programme, Food and Agriculture Organization. Madras, India: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations

|

| [45] |

Pathansali D, Song M K. 1958. Some aspects of cockle (Anadara granosa L.) culture in Malaya. Proceedings of the Indo-Pacific Fisheries, 8(II): 26–31

|

| [46] |

Pauly D. 1983. Some Simple Methods for the Assessment of Tropical Fish Stocks. Rome, Italy: Food and Agriculture Organization

|

| [47] |

Pauly D, David N. 1981. ELEFAN I, a BASIC program for the objective extraction of growth parameters from length-frequency data. Berichte der Deutschen Wissenschaftlichen für Meeresforschung, 28(4): 205–211

|

| [48] |

Pauly D, Munro J L. 1984. Once more on the comparison of growth in fish and invertebrates. The WorldFish Center, 2(1): 1–21

|

| [49] |

Quinn II T J, Deriso R B. 1999. Quantitative Fish Dynamics. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 542

|

| [50] |

Rebelo M F, Amaral M C R, Pfeiffer W C. 2005. Oyster condition index in Crassostrea rhizophorae (Guilding, 1828) from a heavy-metal polluted coastal lagoon. Brazilian Journal of Biology, 65(2): 345–351. doi: 10.1590/S1519-69842005000200019

|

| [51] |

Rifi M, Ounifi-Ben Amor K, Ghanem R, et al. 2015. The condition index: an effective eco-physiological indicator in the invasive cockle Fulvia fragilis. Bulletin de la Societe Zoologique de France, 140(2): 129–149

|

| [52] |

Rosas I, Báez A, Belmont R. 1983. Oyster (Crassostrea virginica) as indicator of heavy metal pollution in some lagoons of the Gulf of Mexico. Water, Air, and Soil Pollution, 20(2): 127–135. doi: 10.1007/BF00279623

|

| [53] |

Sahin C, Düzgüneş E, Okumuş İ. 2006. Seasonal variations in condition index and gonadal development of the introduced blood cockle Anadara inaequivalvis (Bruguiere, 1789) in the Southeastern Black Sea coast. Turkish Journal of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences, 6: 155–163

|

| [54] |

Santoso P, Marsoedi, Maftuch, et al. 2015. Building strategy priority of blood cockle aquaculture development for conservation and welfare in Sub-district of Central Kupang, West Timor, Indonesia. Journal of Biodiversity and Environmental Sciences, 7(4): 34–42

|

| [55] |

Scott G I, Lawrence D R. 1982. The American oyster as a coastal zone pollution monitor: A pilot study. Estuaries, 5(1): 40–46. doi: 10.2307/1352215

|

| [56] |

Sparre P, Venema S C. 1992. Introduction to tropical fish stock assessment. Part 1: Manual. FAO Fisheries Technical Paper. Rome, Italy: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, 192–218

|

| [57] |

Suanrattanachai P, Tiaye R, Theparoonrat Y. 2011. Responsible blood cockle Fisheries Management in Pethchaburi Province, Thailand: an ecosystem approach to fisheries management. Fish for the People, 9(2): 111–114

|

| [58] |

Sugiyama S, Staples D, Funge-Smith S. 2004. Status and potential of fisheries and aquaculture in Asia and the Pacific. Bangkok, Thailand: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, Regional Office for Asia and the Pacific

|

| [59] |

Suwanjarat J, Pituksalee C, Thongchai S. 2009. Reproductive cycle of Anadara granosa at Pattani Bay and its relationship with metal concentrations in the sediments. Songklanakarin Journal of Science and Technology, 31(5): 471–479

|

| [60] |

Tiensongrusmee B, Pontjoprawiro S. 1988. Cockle culture. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations Project Report FAO-FI-INS/81/008/Manual/12. http://www.fao.org/3/AB887E/AB887E00.htm[2020−3−18]

|

| [61] |

Vakily J M. 1992. Determination and comparison of bivalve growth, with emphasis on Thailand and other tropical areas. Technical Reports 36. Manila, Philippines: International Centre for Living Aquatic Resources Management

|

| [62] |

Yurimoto T, Mohd Kassim F, Man A. 2014. Sexual maturation of the blood cockle, Anadara granosa, in Matang mangrove estuary, Peninsular Malaysia. International Journal of Aquatic Biology, 2(3): 115–123. doi: 10.22034/ijab.V2i3.74

|

| 1. | Mawardi Mawardi, M. Ali Sarong, Suhendrayatna Suhendrayatna, et al. Morphometric Analysis and Growth Patterns of Blood Cockle (Tegillarca granosa) in Langsa Mangrove Ecosystems, Indonesia. Grimsa Journal of Science Engineering and Technology, 2024, 2(2): 66. doi:10.61975/gjset.v2i2.55 | |

| 2. | Snigdhodeb Dutta. Population Dynamics of Four Fin Fish Species from a Tropical Estuary. Thalassas: An International Journal of Marine Sciences, 2023, 39(1): 333. doi:10.1007/s41208-023-00527-8 |

| Midlength/mm | Jul. 2017 | Aug. 2017 | Sept. 2017 | Oct. 2017 | Nov. 2017 | Dec. 2017 | Jan. 2018 | Feb. 2018 | Mar. 2018 | Apr. 2018 | May 2018 | Jun. 2018 |

| 27.5 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 32.5 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 37.5 | 3 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 42.5 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 47.5 | 4 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 7 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| 52.5 | 27 | 8 | 1 | 4 | 5 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 1 | 4 |

| 57.5 | 9 | 1 | 3 | 5 | 8 | 0 | 4 | 7 | 7 | 5 | 3 | 9 |

| 62.5 | 5 | 6 | 4 | 3 | 5 | 4 | 2 | 8 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 9 |

| 67.5 | 2 | 4 | 5 | 1 | 9 | 2 | 1 | 4 | 3 | 0 | 2 | 3 |

| 72.5 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 7 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 77.5 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 82.5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Total | 55 | 20 | 20 | 14 | 45 | 13 | 14 | 26 | 19 | 13 | 11 | 29 |

| Note: 0 represents no cockle found. | ||||||||||||

| Location | Species | Condition index (±SD) | Reference |

| Marudu Bay, Malaysia | Tegillarca granosa | 4.98±0.86 | current study |

| Straits of Malacca, Malaysia | Anadara granosa | 6.76±1.13 | Khalil et al. (2017) |

| Black Sea Coast, Turkey | A. granosa | 7.88±1.80 | Sahin et al. (2006) |

| Kakinada Bay, India | A. granosa | 4.11 | Narasimham (1988a) |

| Location | Species | a | b | Reference |

| Marudu Bay, Malaysia | Tegillarca granosa | 0.664 | 2.60 | current study |

| Balik Pulau, Malaysia | Anadara granosa | 0.002 | 2.33 | Mirzaei et al. (2015) |

| Sungai Buloh, Malaysia | A. granosa | 0.240 | 3.37 | Broom (1982) |

| Kakinada Bay, India | A. granosa | 0.260 | 2.12 | Narasimham (1988b) |

| Thailand | A. granosa | 0.360 | 3.04 | Boonruang and Janekarn (1983) |

| Note: a is the intercept (condition factor) and b is the slope (growth coefficient). | ||||

| Location | Species | L∞/mm | K/a–1 | F/a–1 | E | Reference |

| Marudu Bay, Malaysia | Tegillarca granosa | 86.68 | 0.98 | 1.07 | 0.45 | current study |

| Balik Pulau, Malaysia | Anadara granosa | 35.4 | 1.1 | 0.48 | 0.16 | Mirzaei et al.(2015) |

| Kuala Juru, Malaysia | A. granosa | 45 | 0.55 | 2.69 | 0.83 | Oon (1986) |

| Kuala Sepetang, Malaysia | A. granosa | 40.5 | 0.79 | 3.33 | 0.81 | Oon (1986) |

| Sungai Besar Selangor, Malaysia | A. granosa | 41.4 | 0.78 | 2.88 | 0.79 | Oon (1986) |

| Pulau Sangga, Malaysia | A. granosa | 37.2 | 0.88 | 2.05 | 0.7 | Oon (1986) |

| Sungai Buloh, Malaysia | A. granosa | 44.4 | 1.01 | – | – | Broom (1982) |

| Kakinada Bay, India | A. granosa | 73.4 | 0.58 | – | – | Narasimham (1988b) |

| Ang Sila, Thailand | A. granosa | 36.9 | 1.86 | – | – | Vakily (1992) |

| Desa Menco, Indonesia | A. granosa | 129.9 | 0.07 | – | – | Imtihan et al. (2014) |

| Kecamatan Wedung, Indonesia | A. granosa | 112.1 | 0.07 | – | – | Imtihan et al. (2014) |

| Demak, Indonesia | A. granosa | 106.8 | 0.06 | – | – | Imtihan et al. (2014) |

| Note: L∞: estimated asymptotic length; K: growth coefficient; F: estimated fishing mortality; E: estimated exploitation level. | ||||||

| Location | Species | Spawning period | Reference |

| Marudu bay, Malaysia | Tegillarca granosa | March to April and September to October | current study |

| Pulau Pinang, Malaysia | Anadara granosa | February to March and October | Khalil et al. (2017) |

| Pulau Pinang, Malaysia | A. granosa | August to September | Broom (1983) |

| Selangor, Malaysia | A. granosa | September and November | Broom (1983) |

| Phuket, Thailand | A. granosa | October to November | Boonruang and Janekarn (1983) |

| Pattani Bay, Thailand | A. granosa | September and December | Suwanjarat et al. (2009) |

| Banda Aceh, Indonesia | A. granosa | September to October | Khalil et al. (2017) |

| Lhokseumawe, Indonesia | A. granosa | September to October | Khalil et al. (2017) |

| Midlength/mm | Jul. 2017 | Aug. 2017 | Sept. 2017 | Oct. 2017 | Nov. 2017 | Dec. 2017 | Jan. 2018 | Feb. 2018 | Mar. 2018 | Apr. 2018 | May 2018 | Jun. 2018 |

| 27.5 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 32.5 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 37.5 | 3 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 42.5 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 47.5 | 4 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 7 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| 52.5 | 27 | 8 | 1 | 4 | 5 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 1 | 4 |

| 57.5 | 9 | 1 | 3 | 5 | 8 | 0 | 4 | 7 | 7 | 5 | 3 | 9 |

| 62.5 | 5 | 6 | 4 | 3 | 5 | 4 | 2 | 8 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 9 |

| 67.5 | 2 | 4 | 5 | 1 | 9 | 2 | 1 | 4 | 3 | 0 | 2 | 3 |

| 72.5 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 7 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 77.5 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 82.5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Total | 55 | 20 | 20 | 14 | 45 | 13 | 14 | 26 | 19 | 13 | 11 | 29 |

| Note: 0 represents no cockle found. | ||||||||||||

| Location | Species | Condition index (±SD) | Reference |

| Marudu Bay, Malaysia | Tegillarca granosa | 4.98±0.86 | current study |

| Straits of Malacca, Malaysia | Anadara granosa | 6.76±1.13 | Khalil et al. (2017) |

| Black Sea Coast, Turkey | A. granosa | 7.88±1.80 | Sahin et al. (2006) |

| Kakinada Bay, India | A. granosa | 4.11 | Narasimham (1988a) |

| Location | Species | a | b | Reference |

| Marudu Bay, Malaysia | Tegillarca granosa | 0.664 | 2.60 | current study |

| Balik Pulau, Malaysia | Anadara granosa | 0.002 | 2.33 | Mirzaei et al. (2015) |

| Sungai Buloh, Malaysia | A. granosa | 0.240 | 3.37 | Broom (1982) |

| Kakinada Bay, India | A. granosa | 0.260 | 2.12 | Narasimham (1988b) |

| Thailand | A. granosa | 0.360 | 3.04 | Boonruang and Janekarn (1983) |

| Note: a is the intercept (condition factor) and b is the slope (growth coefficient). | ||||

| Location | Species | L∞/mm | K/a–1 | F/a–1 | E | Reference |

| Marudu Bay, Malaysia | Tegillarca granosa | 86.68 | 0.98 | 1.07 | 0.45 | current study |

| Balik Pulau, Malaysia | Anadara granosa | 35.4 | 1.1 | 0.48 | 0.16 | Mirzaei et al.(2015) |

| Kuala Juru, Malaysia | A. granosa | 45 | 0.55 | 2.69 | 0.83 | Oon (1986) |

| Kuala Sepetang, Malaysia | A. granosa | 40.5 | 0.79 | 3.33 | 0.81 | Oon (1986) |

| Sungai Besar Selangor, Malaysia | A. granosa | 41.4 | 0.78 | 2.88 | 0.79 | Oon (1986) |

| Pulau Sangga, Malaysia | A. granosa | 37.2 | 0.88 | 2.05 | 0.7 | Oon (1986) |

| Sungai Buloh, Malaysia | A. granosa | 44.4 | 1.01 | – | – | Broom (1982) |

| Kakinada Bay, India | A. granosa | 73.4 | 0.58 | – | – | Narasimham (1988b) |

| Ang Sila, Thailand | A. granosa | 36.9 | 1.86 | – | – | Vakily (1992) |

| Desa Menco, Indonesia | A. granosa | 129.9 | 0.07 | – | – | Imtihan et al. (2014) |

| Kecamatan Wedung, Indonesia | A. granosa | 112.1 | 0.07 | – | – | Imtihan et al. (2014) |

| Demak, Indonesia | A. granosa | 106.8 | 0.06 | – | – | Imtihan et al. (2014) |

| Note: L∞: estimated asymptotic length; K: growth coefficient; F: estimated fishing mortality; E: estimated exploitation level. | ||||||

| Location | Species | Spawning period | Reference |

| Marudu bay, Malaysia | Tegillarca granosa | March to April and September to October | current study |

| Pulau Pinang, Malaysia | Anadara granosa | February to March and October | Khalil et al. (2017) |

| Pulau Pinang, Malaysia | A. granosa | August to September | Broom (1983) |

| Selangor, Malaysia | A. granosa | September and November | Broom (1983) |

| Phuket, Thailand | A. granosa | October to November | Boonruang and Janekarn (1983) |

| Pattani Bay, Thailand | A. granosa | September and December | Suwanjarat et al. (2009) |

| Banda Aceh, Indonesia | A. granosa | September to October | Khalil et al. (2017) |

| Lhokseumawe, Indonesia | A. granosa | September to October | Khalil et al. (2017) |