| Citation: | Wenjin Sun, Jingsong Yang, Wei Tan, Yu Liu, Baojun Zhao, Yijun He, Changming Dong. Eddy diffusivity and coherent mesoscale eddy analysis in the Southern Ocean[J]. Acta Oceanologica Sinica, 2021, 40(10): 1-16. doi: 10.1007/s13131-021-1881-4 |

Mesoscale eddies are prevalent in global ocean. They contain a large portion of the oceanic kinetic energy, and act as a linkage between the large-scale motions and sub-mesoscale motions in the energy cascade (Rhines, 2001; Ferrari and Wunsch, 2009). Previous studies on mesoscale eddy can be mainly divided into two categories. One focused on the transient mesoscale eddy, which is defined as the deviation from the large-scale average. The transient mesoscale eddy is usually obtained by a filtering method, such as temporal filtering method (McDougall and McIntosh, 1996), spatial filtering method (Bachman and Fox-Kemper, 2013; Haigh et al., 2020) and temporal-spatial filtering method (Lu et al., 2016). Therefore, a transient mesoscale eddy is actually a mesoscale process, including coherent mesoscale eddy, mesoscale frontal, mesoscale meander and other mesoscale phenomena. The other studies focused on coherent mesoscale eddy, which is characterized by a clear eddy boundary (Nencioli et al., 2010; Ni et al., 2020), approximate planar oval in shape (Wang et al., 2015; He et al., 2018), multiple three-dimensional structures (Hu et al., 2011; Zhang et al., 2013, 2014, 2016; Lin et al., 2015; Waite et al., 2016; Sun et al., 2017), and determined eddy lifespan (Chelton et al., 2011; Sun et al., 2018). The coherent mesoscale eddy is usually identified by an eddy detection algorithm, such as the vector geometry-based method (Nencioli et al., 2010), Okubo–Weiss method (Okubo, 1970; Weiss, 1991) and winding-angle method (Sadarjoen and Post, 2000).

The climate models with coarse resolutions fail to resolve mesoscale processes, therefore, it is necessary to parameterize the effects of transient mesoscale eddy (Marshall et al., 2006; Eden, 2006; Eden et al., 2007; Vollmer and Eden, 2013; Klocker and Abernathey, 2014; Bachman et al., 2017; Li et al., 2018; Poulsen et al., 2018; Canuto et al., 2019; Fox-Kemper et al., 2019). Even in the eddy-resolving models, the eddy diffusivity parameterization is still needed (Gent, 2011). Currently, the Gent-McWilliams parameterization (Gent and McWilliams, 1990, GM90 hereafter) is the most popular scheme used in climate models. It parameterizes the influence of transient mesoscale eddies on stratification, particularly the release of available potential energy by baroclinic transient mesoscale eddies.

A bunch of studies later proposed various revisions to the GM90 parameterization scheme and eddy diffusivity calculation methods. These studies can be separated into three categories. The first category provides an eddy diffusivity formula directly expressed by large-scale parameters, based on theory or empirical (Vollmer and Eden, 2013; Klocker and Abernathey, 2014; Griesel et al., 2015; Mak et al., 2016; Chapman and Sallée, 2017; Nummelin et al., 2021). One of these formulae is

The second category to calculate eddy diffusivity is based on observed or simulated Lagrangian trajectory (Chiswell, 2013; Griesel et al., 2014; Wolfram et al., 2015; Rypina et al., 2016). Using the Diapycnal and Isopycnal Mixing Experiment data, LaCasce et al. (2014) estimated eddy diffusivity through several methods, and found that different methods yield a consistent eddy diffusivity of (800±200) m2/s in the Southern Ocean. Recently, a Bayesian approach method is developed to derive eddy diffusivity field from Lagrangian trajectory data (Ying et al., 2019). This method not only proves the capability of estimating the space-variant anisotropic eddy diffusivity from a modest amount of data but also provides a measurement of the uncertainty of the estimates.

The third category calculates eddy diffusivity directly, based on high-resolution models output (Solovev et al., 2002; Abernathey et al., 2013; Bachman et al., 2015; Lu et al., 2016; Poulsen et al., 2018; Grooms and Kleiber, 2019; Haigh et al., 2020). Based on the output from an eddy-resolving model (1/12)°, the formula

In the study of coherent mesoscale eddies, Frenger et al. (2015) adopted multi-source observation data, including satellite observations of sea level anomalies, sea surface temperature, and in situ temperature and salinity measurements from Argo profiling floats, to propose a detailed report about coherent mesoscale eddies in the Southern Ocean. During 1997–2010, based on the Okubo–Weiss method, they identified over a million instances of coherent mesoscale eddies and tracked about 105 of them over one month or more. They pointed out that the coherent mesoscale anticyclone eddies tend to dominate the southern subtropical gyres, and the coherent mesoscale cyclone eddies are mainly located in the northern flank of the Antarctic Circumpolar Current. On average, the long-lived coherent mesoscale eddies (with more than one month lifespan) have a diameter of 85 km, an amplitude of 12 cm, a propagation speed of 0.04 m/s, lateral turnover times of 24 d, a lifespan of 10 weeks, and a propagation distance of 124 km. Coherent mesoscale eddy can extend downward to at least 2 000 m, which is the maximum depth of an Argo profile. The vertical-averaged (down to 2 000 m) temperature anomaly at the coherent mesoscale eddy center is about ±0.5°C, and the corresponding density anomaly is about ±0.05–0.01 kg/m3.

In the Southern Ocean, the coherent mesoscale eddies have great influences on geobiochemical cycle (Adams et al., 2017; Hausmann et al., 2017; Dawson et al., 2018; Frenger et al., 2018; Ellwood et al., 2020; Patel et al., 2020). For instance, a coherent cold-core cyclonic eddy detached from the Subantarctic Front and entered the Subantarctic Zone in March 2016, compared with the surrounding Subantarctic Zone waters, the eddy was relatively biologically unproductive and dissolved inorganic carbon rich, and was identified as a strong carbon dioxide source to the atmosphere (Moreau et al., 2017). Besides, the effect of coherent mesoscale eddies on chlorophyll concentration has obvious seasonal dependence. In the Antarctic Circumpolar Current region, the coherent mesoscale anticyclonic (cyclonic) eddies have elevated (depressed) chlorophyll biomass in summer, while the reverse applies in winter (Song et al., 2018; Rohr et al., 2020). On average, the coherent mesoscale cyclonic (anticyclonic) eddies can drive negative (positive) net population growth rate anomalies, reduce (increase) dilution across shallower (deeper) mixed layers, and advect biomass downward (upward) via eddy-induced Ekman pumping. The net contribution to biomass anomalies can exceed 10%–20% of background levels at the regional scale (Rohr et al., 2020). Coherent mesoscale cyclonic eddy also could lead to a decreasing of near-surface wind speeds, a decline in cloud fraction and water content, and a reduction in rainfall. While, the opposite is true in coherent mesoscale anticyclonic eddy (Frenger et al., 2013; Byrne et al., 2016).

To sum up, there are a collection of works that study eddy diffusivity and coherent mesoscale eddies separately. An important reason is that transient mesoscale eddies are used in the study of eddy diffusivity, while coherent mesoscale eddies are used to explore eddy characteristics and their effects. However, as a kind of mesoscale phenomena with coherent three-dimensional structure, the coherent mesoscale eddies are an important part of the transient mesoscale eddies. Therefore, it is beneficial to present these two issues together and study the relationship between them for a comprehensive understanding of mesoscale phenomena in the Southern Ocean. Based on this consideration, this study focuses on three main parts: (1) the spatial distribution of eddy diffusivity; (2) the basic characteristics of coherent mesoscale eddy; and (3) the relationship between eddy diffusivity and coherent mesoscale eddy in the Southern Ocean.

The remaining parts of this work are organized as follows. The description of the data and methods used in this study are presented in Section 2. Section 3 gives the data validation. The three-dimensional spatial distribution of eddy diffusivity is presented in Section 4. The basic characteristics of coherent mesoscale eddies, including three-dimensional structures, eddy number, radius, intensity, penetration depth and lifespan, are illustrated in Section 5. In Section 6, the relationship between normalized eddy diffusivity and coherent mesoscale eddy activity is analyzed. Finally, the summary and conclusions are given in Section 7.

In this study, the Southern Ocean State Estimate data (SOSE, Mazloff et al., 2010) are used for the calculation of mesoscale eddy diffusivity and the identification of coherent mesoscale eddy. This dataset has been successfully applied to many mesoscale eddy works (Lu and Speer, 2010; Lu et al., 2016; Haller et al., 2016). The SOSE data are derived from Massachusetts Institute of Technology general circulation model, and its assimilation software is developed by the Estimating the Circulation and Climate of the Ocean consortium. This model covers the period from January 2005 to December 2010, and the simulation domain extends from 25°S to 78°S. The model is configured on a (1/6)° by (1/6)° horizontal resolution and 42 uneven vertical layers. The vertical spacing increases from 10 m at the surface to 250 m at/below 2 450 m. Considering that the temporal resolution is 5 d, 438 snapshots of potential three-dimensional variables are available during the six-year period. In addition to the usual variables such as temperature, salinity, veolicity, this dataset also contains neutral density calculated by the software as described by Jackett and McDougall (1997).

To validate the performance of the SOSE data, the AVISO (Archiving, Validation, and Interpretation of Satellite Oceanographic) sea surface height data are used. It merges several satellite altimeter measurements to obtain a daily product, with a horizontal resolution of (1/4)° by (1/4)°. The same period (January 2005 to December 2010) is chosen to match the SOSE data. For more details about this dataset, please refer to Pujol et al. (2016).

Previous studies have shown that oceanic mixing processes occur along or perpendicular to neutral density surfaces rather than along horizontal or vertical directions (McDougall, 1987; Gent, 2011). McDougall and McIntosh (2001) emphasized that transient mesoscale eddy flux needs to be weighted by isoneutral layer thickness. That means the calculation of eddy diffusivity should be carried out in isoneutral coordinate. Therefore, the numerical model output (with Cartesian coordinate system) need be transformed to the isoneutral coordinate system firstly. On the other hand, the Cartesian coordinate system is still needed for better illustration of the eddy diffusivity. In summary, the reciprocal transformation between Cartesian coordinate and isoneutral coordinate systems is needed. For more details, please refer to Appendix.

A temporal scale of 365 d and a spatial scale of 3° by 3° are selected as the threshold value between large-scale and mesoscale signals (Lu et al., 2016), i.e., a physical process longer than 365 d or larger than 3° is considered as large-scale information, and the rest is defined as mesoscale information. Thus, an arbitrary variable (

| $$ \varphi = \bar \varphi + \varphi ' {\rm{,}} $$ | (1) |

where

The mesoscale eddy thickness flux

| $$ \overline {{\boldsymbol{u}}'{{h'_\rho} }} = - {{\boldsymbol{K}}_h}\nabla {\bar h_\rho } {\rm{,}} $$ | (2) |

where

| $$ \overline {{\boldsymbol{u}}'{{h'_\rho} }} = - \kappa \nabla {\bar h_\rho } . $$ | (3) |

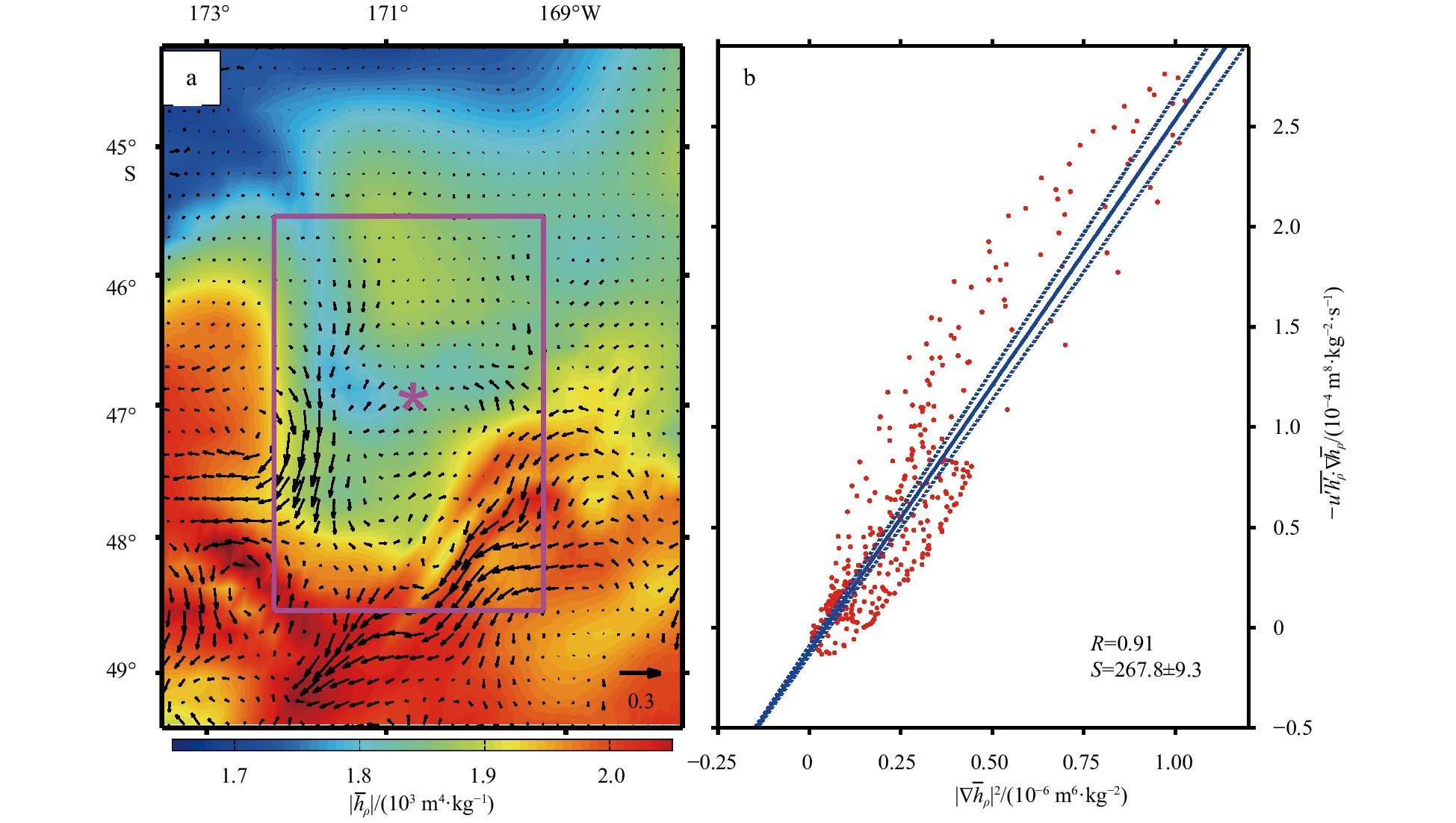

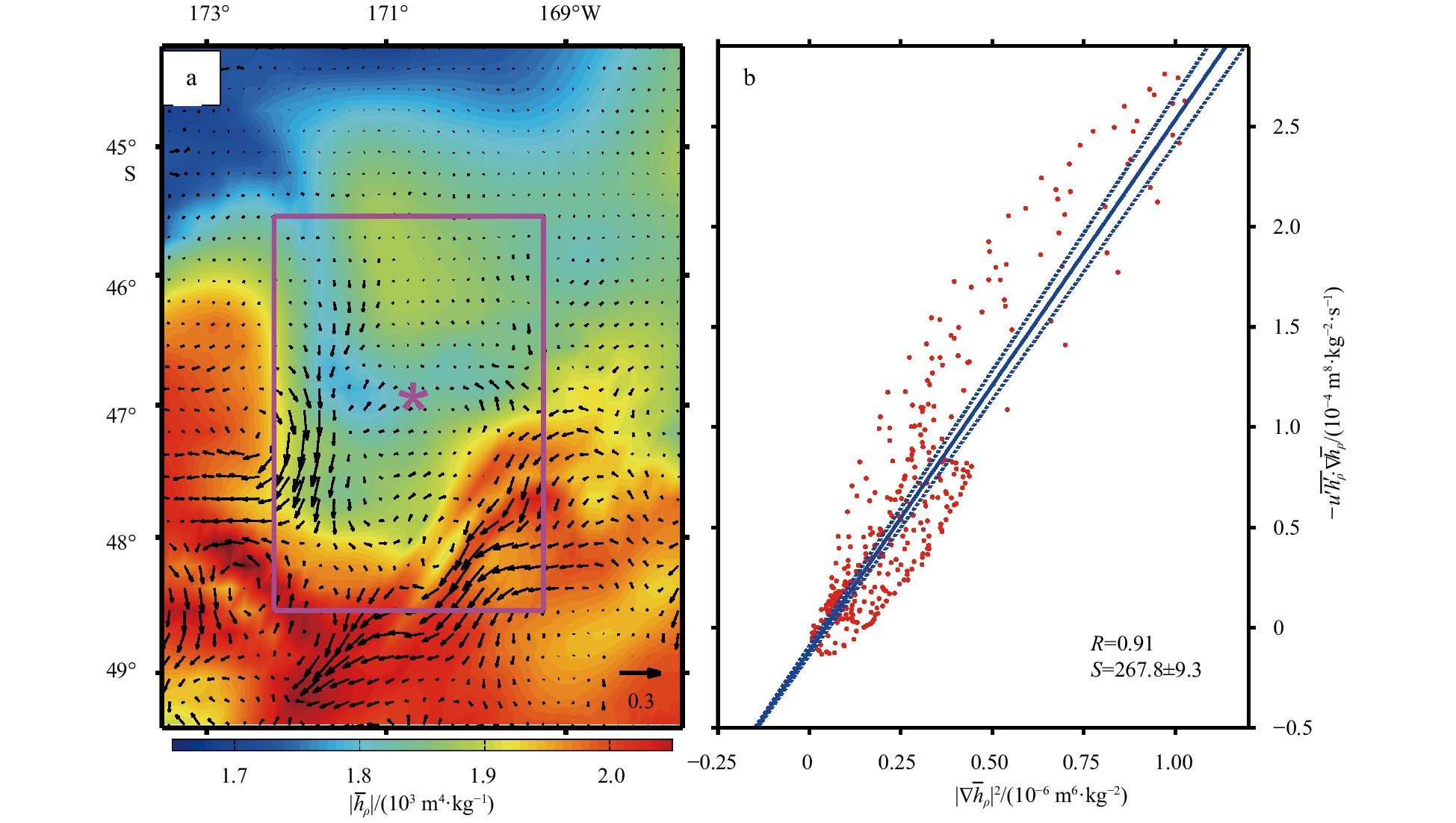

The local mesoscale fluctuation is not only associated with the local large-scale gradient, but also influenced by upstream and downstream advection, especially in the Southern Ocean (Chen et al., 2014), therefore, the linear regression analysis is used to obtain the eddy diffusivity. It should be noted that the horizontal resolution of the SOSE data is (1/6)° by (1/6)°, it can distinguish the coherent mesoscale eddies. However, the data resolution is insufficient to portray the diffusion process in coherent mesoscale eddies which is on a smaller scale. Therefore, the

The automated two-dimensional coherent mesoscale eddy detection and tracking algorithm (Nencioli et al., 2010) is adopted in this study. This algorithm is based on the velocity geometric characteristics of the coherent mesoscale eddy, and has been successfully applied to many researches (Couvelard et al., 2012; Aguiar et al., 2013; Dong et al., 2014; Ji et al., 2017; Liu et al., 2017; Sun et al., 2018, 2019; Yang et al., 2020). Simply, this algorithm contains three steps:

First step: locating the two-dimensional coherent mesoscale eddy center which satisfies the following four geometrical constraints.

(1) The meridional velocity (

(2) Similar to (1), the zonal velocity (

(3) The horizontal velocity (

(4) Construct a local two-dimensional Cartesian coordinate system with the origin as a possible coherent mesoscale eddy center. The abscissa and ordinate denote zonal and meridional directions, respectively. In two adjacent or the same quadrants, the direction of the velocity vector

Second step: defining the eddy boundary for each eddy center. In this study, the outermost contour of the local stream function, which encloses a coherent mesoscale eddy center, is defined as the eddy boundary.

Third step: two-dimensional coherent eddy tracking. Considering the temporal resolution of the SOSE data (5 d) and average velocity of the background field in the Southern Ocean (about 0.15 m/s), a circular search area with a 1.2° radius is chosen to track the coherent mesoscale eddy. If a two-dimensional coherent eddy is successfully detected at time step

Applying this eddy automated detection method to each vertical layer, discrete two-dimensional coherent mesoscale eddies datebase is obtained. Figure 2 shows a sample distribution of two-dimensional coherent mesoscale eddies in an arbitrary area of the Southern Ocean at sea surface on February 25, 2005. The blue (red) curves indicates the boundaries of coherent mesoscale cyclonic (anticyclonic) eddies. The black asterisks indicate the eddy centers. There are abundant coherent mesoscale eddies in the Southern Ocean, and this method can successfully identify them.

The three-dimensional eddy detection method (Dong et al., 2012) is also used. This method is based on three conditions: (1) the same eddy should have the same occurrence time at each level; (2) the same eddy also should have the same polarity at each level; (3) the drift distance of the eddy center is no farther than a quarter of its radius between two neighboring vertical levels. The eddy center is iterated downward until the new eddy center cannot be found at the next level. Finally, a three-dimensional coherent mesoscale eddy dataset is produced, which contains coherent mesoscale eddy polarity, generated time, vertical penetration depth, radius (defined as the radius of a circle that has the same area with the recognized eddy), center and horizontal boundary at each level.

Three screening conditions are introduced in this study to reduce uncertainties in different detection and tracking methods of the coherent mesoscale eddies: (1) considering that the characteristic time scale of the coherent mesoscale eddies is in several weeks, only the eddies surviving equal to or longer than 30 days are selected; (2) since the spatial scale of the coherent mesoscale eddies is O (100 km)–O (50 km) from 30°S to 65°S (Chelton et al., 2011) and the model resolution is (1/6)° by (1/6)°, only the eddies with an average radius larger than 30 km are singled out; (3) for a better representation of the coherent mesoscale eddies, only the eddies with a vertical penetration depth more than 100 m are selected.

Derived from the SOSE data, the sea surface height anomaly (SSHA) is negative in high latitude and positive in low latitude of the Southern Ocean (Fig. 3a), and it is consistent with the AVISO SSHA (Fig. 3b). The multi-year and spatial average SSHA from SOSE (AVISO) is (−0.23±0.66) m ((0.0 ± 0.65) m). The variance of the SOSE data is 0.04 m2 compared with the AVISO data. In addition, the sea surface eddy kinetic energy (EKE) also shows good agreement between the two datasets (Figs 3c and d). The sea surface EKE is energetic to the north of the Subpolar Antarctic Front (SAF), and weak on the southern side of the Antarctic Front (AF, Fig. 3d). In this study, the SAF is defined as the 4°C isotherm at 200 m depth (Orsi et al., 1993), and the AF is defined as the location with the minimum salinity at 200 m depth (Gordon et al., 1978). The average sea surface EKE is (136.5±256) cm2/s2 from the SOSE data, which is slightly lower than the AVISO result ((169.7±265) cm2/s2). Compared with the AVISO data, the variance of the sea surface EKE from the SOSE data is 6.3 cm4/s4. In addition, the probability density distribution of the SSHA and EKE is also calculated, and similar results are obtained between the two datasets (figure not shown), further confirming the reliability of SOSE data.

The spatial distribution of the eddy diffusivity in the Southern Ocean is shown in Fig. 4. Figures 4a and b are displayed in the isoneutral coordinate system, corresponding to the 27.15–27.20 kg/m3 and 27.95–28.00 kg/m3 isoneutral layers. Figures 4c and d are displayed in the Cartesian coordinate system, corresponding to 60–72 m and 826–1 092 m layers. In general, the magnitude of the eddy diffusivity is on the order of O (103 m2/s), which is close to the typical value applied in non-eddy-resolving ocean models. However, as noted in Fig. 4 and some previous literature (Gent, 2011; Lu et al., 2016; Bachman et al., 2020; Stanley et al., 2020), the eddy diffusivity has noticeable spatial variation. Positive eddy diffusivity implies the local production of EKE obtaining energy from large-scale mean flow. On the contrary, negative eddy diffusivity corresponds to the mesoscale eddy releasing energy to large-scale mean flow (Eden et al., 2007). The distribution of negative eddy diffusivity is irregular (Fig. 4a), this may be related to the fact that the negative eddy diffusivity is influenced by several processes, such as the rotational eddy flux (Marshall and Shutts, 1981; Bryan et al., 1999; Medvedev and Greatbatch, 2004; Eden et al., 2007), advection of thickness variance and enstrophy (Treguier et al., 1997; Bachman and Fox-Kemper, 2013), and stationary mesoscale eddy flux (Lu et al., 2016). Besides, Marshall et al. (2006) believed that the estimated eddy diffusivity more accurately corresponds to the dianeutral thickness diffusivity in the upper layer. Figure 5 shows that the negative eddy diffusivity mainly appears in the upper layer of the ocean indeed, in agreement with Marshall et al. (2006). That is, the negative value represents the occurrence of the dianeutral process, indicating that the original calculation Eq. (3) cannot be accurately established. This is an interesting and important issue but is beyond our present scope.

Although the results in this study are similar to those in previous literature, there are some differences in the calculation method of eddy diffusivity. (1) This study uses the isoneutral coordinate system, which is closer to the real physical process in the ocean, compared with the Cartesian coordinate system (Eden et al., 2007) and potential density coordinate system (Bryan et al., 1999; Lu et al., 2016); (2) normalized thickness of the isoneutral layer is adopted as a passive tracer to calculate the eddy diffusivity in this study, instead of buoyancy (Treguier et al., 1997; Eden et al., 2007), and potential vorticity (Marshall et al., 2012; Bachman et al., 2017); (3) the linear regression in a 3° by 3° box is performed to calculate the eddy diffusivity. This method can avoid the division issue that the denominator is close to zero; (4) the temporal-spatial filtering scheme is adopted in this study, this can avoid the influence of Leonard and Clark terms more easily, compared with the spatial filtering method (Bachman and Fox-Kemper, 2013); (5) compared with the derived tracer transport (Marshall et al., 2006), which only gave the surface eddy diffusivity in the Southern Ocean, this study further demonstrates the vertical distribution of the eddy diffusivity.

Figure 5 is the zonal mean of the eddy diffusivity in the isoneutral coordinate system (Fig. 5a) and Cartesian coordinate system (Fig. 5b). In the meridional direction, the eddy diffusivity is obviously larger between the northern flank of the SAF (about 52.3°S) and about 40°S (Fig. 5a). In the vertical direction, the eddy diffusivity is mainly concentrated within the upper 50 m, and then it rapidly decays with depth. These distribution characteristics of the eddy diffusivity are consistent with Eden et al. (2007).

By converting the results from the isoneutral coordinate to the Cartesian coordinate system, the eddy diffusivity is obviously higher under the SAF and AF region (Fig. 5b). The enhanced area reaches about 3 000-m depth (near the 28.3 kg/m3 isoneutral level). Abernathey et al. (2010) suggested that this phenomenon is attributed to a “critical layer” in which the eddy phase speed equals the mean flow speed. Besides, the deeper vertical penetration depth and stronger intensity of the coherent mesoscale eddies are also found to be important in this study. For a more detailed description, please refer to Subsection 5.5. To sum up, the eddy diffusivity is on the order of O (103 m2/s) and shows an evident spatial variation in the Southern Ocean.

Two cases of the eddies (with bold dotted boundaries in Fig. 2) are selected, and their three-dimensional structures (Figs 6a and c) and vertical distributions of the normalized eddy intensity (Figs 6b and d) are shown in Fig. 6. The radius of the coherent mesoscale cyclonic (anticyclonic) eddy is 96.5 km (72.6 km) at sea surface, and almost keeps unchanged to its bottom (about 1 173.5 m, Figs 6a and c). The vertical penetration depth of the coherent mesoscale eddy is 1 173.5 m, as the automated eddy detection program could not detect the presence of the eddy in the next layer (1 348.5 m) below 1 173.5 m. Below 900 m, the temperature anomalies become very small and is almost negligible for both coherent mesoscale cyclonic eddy and anticyclonic eddy (xoz and yoz coordinate plane in Figs 6a and c). In a word, coherent mesoscale eddy-induced temperature anomalies decrease with depth, while the radius has less change from surface to 1 173.5 m.

The intensity of coherent mesoscale eddies can be expressed by several physical parameters, such as EKE, relative vorticity and deformation rate. These parameters reflect the characteristics of a coherent mesoscale eddy from different aspects. Considering the wide latitude span of the Southern Ocean,

There are two methods to calculate the number of coherent mesoscale eddies. One is the eddy lifespan counting (ELC) method: a whole lifespan of successive coherent mesoscale eddies is considered as one eddy (Chelton et al., 2011; Chen et al., 2012; Aguiar et al., 2013). The other one is the eddy snapshot counting (ESC) method: the eddy number depends on how many coherent mesoscale eddies are identified from each snapshot (Chen et al., 2011; Dong et al., 2012; Frenger et al., 2013; He et al., 2018; Sun et al., 2018; Yang et al., 2020). The number of coherent mesoscale eddies recognized by the ESC method reflects the frequency of eddies occurring at a certain spatial location during the statistical time period. A larger number (i.e., more eddies identified by the ESC method) indicates a higher frequency or probability of eddies appearing at this location. In general, the coherent mesoscale eddies tend to travel long distances throughout their lifespan (Chelton et al., 2011). The ELC method can only reflect the average position of eddies, but cannot accurately find the position with higher/lower probability of eddies. In addition, the radius, intensity and vertical penetration depth of the eddy are constantly changing during its lifetime (Sun et al., 2018). The ELC method may regard several eddy snapshots in the whole lifespan as one eddy, which cannot accurately reflect the spatial and temporal changes of the above-mentioned characteristics of the eddy. Therefore, the ESC method is used in this study, except when calculating the lifespan of the coherent mesoscale eddy. During 2005–2010, eddies are concentrated between the northern side of the SAF to 45°S for both coherent mesoscale cyclonic eddies (Fig. 7a) and anticyclonic eddies (Fig. 7b). The maximum eddy number appears at 47°S for coherent mesoscale cyclonic eddy (361.2±4.7) a−1 and 51°S for coherent mesoscale anticyclonic eddy (414.3±5.6) a−1. In upper 3 000 m, the eddy number between the northern side of the SAF to 45°S is significantly larger than in other regions. This implies that more coherent mesoscale eddies reside and penetrate more deeply in this area. A more detailed description of the eddy penetration depth is given in Subsection 5.5.

In the open ocean, the radius of coherent mesoscale eddies is mainly constrained by the first baroclinic Rossby deformation radius (

As discussed in Subsection 5.1 (Figs 6b and d), the larger eddy intensity is mostly concentrated in the upper ocean (Fig. 9). For cyclonic eddies (Fig. 9a), the normalized intensity greater than 0.1 is concentrated in the upper 500 m between 57°S to 35°S. The 0.05-isoline of the normalized intensity exhibits a bowl-shaped distribution, which is the deepest (about 1 500 m) around 50°S to 45°S, and gradually shoals to the north and south sides. However, for anticyclonic eddies (Fig. 9b), there seems an abrupt deepening of 0.1-isoline and 0.05-isoline around 38°S, indicating the most enegetic anticyclones here. Actually, the similar abrupt deepening also occurs for cyclonic eddies, but with a weaker magnitude. Such a boom of the eddy intensity around 38°S deserves further investigation in the future.

It can be inferred from Fig. 7 that the vertical penetration depth of coherent mesoscale eddies is deeper in the SAF and its northern region than in other regions, and it is confirmed in Fig. 10a. The multi-year average maximum penetration depth of the coherent mesoscale cyclonic eddy is (2 139.5±329.1) m at 43°S, and it is (1 953.6±304.1) m at 45°S for anticyclonic eddy.

The lifespan of coherent mesoscale eddies also changes with latitude (Fig. 10b). It is worth noting that only the eddies surviving more than 30 days are retained in this study (Subsection 2.4). Consistent with the penitration depth, the lifespan of the coherent mesoscale eddy (both cyclonic and anticyclonic) between the SAF and 38°S is longer than that in other areas as well. The multi-year average longest lifespan of the coherent mesoscale cyclonic eddy is (83.3±3.9) d at 46°S, and it is (81.0±5.9) d at 44°S for anticyclonic eddy.

The most immediate cause of this phenomenon (i.e., deeper penetration depth and longer survival time between the northern side of the SAF to 38°S) may be attributed to the larger local wind stress in this region (Fig. 10c). The Pearson correlation coefficient between normalized wind stress and normalized cyclonic (anticyclonic) eddy penetration depth is 0.69 (0.74). This implies that the coherent mesoscale eddies is more vigorous in this region, which can be also inferred from the distribution of sea surface EKE in Fig. 3d.

The scatterplots of normalized eddy activity (

Overall, the normalized eddy activities of coherent mesoscale cyclonic eddies (Fig. 11a), anticyclonic eddies (Fig. 11b) and all the eddies regardless of polarity (Fig. 11c) have a significant positive correlation with the normalized volume-averaged eddy diffusivity. The slope of the regressed line is 0.58

This study focuses on three issues: (1) the distribution of eddy diffusivity; (2) the basic characteristics of coherent mesoscale eddy; and (3) the relationship between coherent mesoscale eddy and eddy diffusivity in the Southern Ocean. Based on the SOSE data and linear regression analysis, the three-dimensional structure of eddy diffusivity is revealed. All the calculations of eddy diffusivity are carried out in an isoneutral coordinate system. This study finds that the eddy diffusivity is on the order of O (103 m2/s) and has an evident spatial variation in the Southern Ocean.

Through two coherent mesoscale eddy cases, it is found that the radius of the coherent mesoscale eddy can be maintained unchanged to deeper than 1 000 m in vertical direction, while the eddy-induced temperature changes are concentrated in upper 900 m. The coherent mesoscale eddies are concentrated from the northern side of the SAF to 45°S. The average penetration depth is deeper and the lifespan is longer in this area than in other areas. In the upper ocean, the radius of the coherent mesoscale eddy (both cyclonic and anticyclonic) is associated with the first baroclinic Rossby deformation radius. Attributed to the effects of the bottom topography in the Southern Ocean, the variation of the eddy radius with latitude is more complex below about 2 000 m.

The intensity of coherent mesoscale eddy is mainly concentrated in the upper ocean, and its normalized value is less than 0.05 deeper than 1 500 m. The average vertical penetration depth of the eddy is also about 1 500 m. The normalized coherent mesoscale eddy activity and the normalized eddy diffusivity have a good linear correlation. Moreover, the coherent mesoscale eddy may plays an important role in eddy diffusivity.

Investigating the spatial distribution of eddy diffusivity and the basic characteristics of coherent mesoscale eddies enriches our understanding of mesoscale processes. Explanation of the relationship between coherent mesoscale eddies and eddy diffusivity is helpful to figure out the contribution of coherent mesoscale eddies to eddy diffusivity. Besides, it also provides a reference for the improvement of mesoscale eddy parameterization schemes.

The Southern Ocean State Estimate (SOSE) data are downloaded from http://sose.ucsd.edu/sose_stateestimation_data_08.html, and computational resources for SOSE are supported by NSF XSEDE resource grant (OCE130007). The altimeter products are produced by the Ssalto/Duacs and distributed by AVISO, with support from the Centre National d’Etudes Spatiales (http://www.aviso.oceanobs.com/duacs/). We thank Hailong Liu (Institute of Atmospheric Physicals, Chinese Academy of Sciences), Jianhua Lu (Sun Yat-Sen University) and Fuchang Wang (Shanghai Jiao Tong University) for the constructive discussion. We thank Matthew Mazloff (Scripps Institution of Oceanography) for the kindly help in data download. We also thank two anonymous reviewers for their constructive comments and helpful suggestions.

| [1] |

Abernathey R, Ferreira D, Klocker A. 2013. Diagnostics of isopycnal mixing in a circumpolar channel. Ocean Modelling, 72: 1–16. doi: 10.1016/j.ocemod.2013.07.004

|

| [2] |

Abernathey R, Marshall J, Mazloff M, et al. 2010. Enhancement of mesoscale eddy stirring at steering levels in the Southern Ocean. Journal of Physical Oceanography, 40(1): 170–184. doi: 10.1175/2009JPO4201.1

|

| [3] |

Adams K A, Hosegood P, Taylor J R, et al. 2017. Frontal circulation and submesoscale variability during the formation of a Southern Ocean mesoscale eddy. Journal of Physical Oceanography, 47(7): 1737–1753. doi: 10.1175/JPO-D-16-0266.1

|

| [4] |

Aguiar A C B, Peliz Á, Carton X. 2013. A census of Meddies in a long-term high-resolution simulation. Progress in Oceanography, 116: 80–94. doi: 10.1016/j.pocean.2013.06.016

|

| [5] |

Bachman S, Fox-Kemper B. 2013. Eddy parameterization challenge suite I: Eady spindown. Ocean Modelling, 64: 12–28. doi: 10.1016/j.ocemod.2012.12.003

|

| [6] |

Bachman S D, Fox-Kemper B, Bryan F O. 2015. A tracer-based inversion method for diagnosing eddy-induced diffusivity and advection. Ocean Modelling, 86: 1–14. doi: 10.1016/j.ocemod.2014.11.006

|

| [7] |

Bachman D, Fox-Kemper B, Bryan F O. 2020. A diagnosis of anisotropic eddy diffusion from a high-resolution global ocean model. Journal of Advances in Modeling Earth Systems, 12(2): e2019MS001904

|

| [8] |

Bachman S D, Marshall D P, Maddison J R, et al. 2017. Evaluation of a scalar eddy transport coefficient based on geometric constraints. Ocean Modelling, 109: 44–54. doi: 10.1016/j.ocemod.2016.12.004

|

| [9] |

Bryan K, Dukowicz J K, Smith R D. 1999. On the mixing coefficient in the parameterization of bolus velocity. Journal of Physical Oceanography, 29(9): 2442–2456. doi: 10.1175/1520-0485(1999)029<2442:OTMCIT>2.0.CO;2

|

| [10] |

Byrne D, Münnich M, Frenger I, Gruber N. 2016. Mesoscale atmosphere ocean coupling enhances the transfer of wind energy into the ocean. Nature Communications, 7: s11867. doi: 10.1038/ncomms11867

|

| [11] |

Canuto V M, Cheng Y, Howard A M, et al. 2019. Three-dimensional, space-dependent mesoscale diffusivity: derivation and implications. Journal of Physical Oceanography, 49(4): 1055–1074. doi: 10.1175/JPO-D-18-0123.1

|

| [12] |

Chapman C, Sallée J B. 2017. Isopycnal mixing suppression by the Antarctic Circumpolar Current and the Southern Ocean meridional overturning circulation. Journal of Physical Oceanography, 47(8): 2023–2045. doi: 10.1175/JPO-D-16-0263.1

|

| [13] |

Chelton D B, de Szoeke R A, Schlax M G, et al. 1998. Geographical variability of the first baroclinic Rossby radius of deformation. Journal of Physical Oceanography, 28(3): 433–460. doi: 10.1175/1520-0485(1998)028<0433:GVOTFB>2.0.CO;2

|

| [14] |

Chelton D B, Schlax M G, Samelson R M. 2011. Global observations of nonlinear mesoscale eddies. Progress in Oceanography, 91(2): 167–216. doi: 10.1016/j.pocean.2011.01.002

|

| [15] |

Chen Ru, Flierl G R, Wunsch C. 2014. A description of local and nonlocal eddy-mean flow interaction in a global eddy-permitting state estimate. Journal of Physical Oceanography, 44(9): 2336–2352. doi: 10.1175/JPO-D-14-0009.1

|

| [16] |

Chen Gengxin, Gan Jianping, Xie Qiang, et al. 2012. Eddy heat and salt transports in the South China Sea and their seasonal modulations. Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans, 117: C05021

|

| [17] |

Chen Gengxin, Hou Yijun, Chu Xiaoqing. 2011. Mesoscale eddies in the South China Sea: Mean properties, spatiotemporal variability, and impact on thermohaline structure. Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans, 116: C06018

|

| [18] |

Chiswell S M. 2013. Lagrangian time scales and eddy diffusivity at 1000 m compared to the surface in the South Pacific and Indian oceans. Journal of Physical Oceanography, 43(12): 2718–2732. doi: 10.1175/JPO-D-13-044.1

|

| [19] |

Couvelard X, Caldeira R M A, Araújo I B, et al. 2012. Wind mediated vorticity-generation and eddy-confinement, leeward of the Madeira Island: 2008 numerical case study. Dynamics of Atmospheres and Oceans, 58: 128–149. doi: 10.1016/j.dynatmoce.2012.09.005

|

| [20] |

Dawson H R S, Strutton P G, Gaube P. 2018. The unusual surface chlorophyll signatures of Southern Ocean eddies. Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans, 123(9): 6053–6069. doi: 10.1029/2017JC013628

|

| [21] |

Dong Changming, Lin Xiayan, Liu Yu, et al. 2012. Three-dimensional oceanic eddy analysis in the Southern California Bight from a numerical product. Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans, 117(C7): C00H14

|

| [22] |

Dong Changming, McWilliams J C, Liu Yu, et al. 2014. Global heat and salt transports by eddy movement. Nature Communications, 5: 3294. doi: 10.1038/ncomms4294

|

| [23] |

Eden C. 2006. Thickness diffusivity in the Southern Ocean. Geophysical Research Letters, 33(11): L11606

|

| [24] |

Eden C, Greatbatch R J. 2008. Towards a mesoscale eddy closure. Ocean Modelling, 20(3): 223–239. doi: 10.1016/j.ocemod.2007.09.002

|

| [25] |

Eden C, Greatbatch R J, Willebrand J. 2007. A diagnosis of thickness fluxes in an eddy-resolving model. Journal of Physical Oceanography, 37(3): 727–742. doi: 10.1175/JPO2987.1

|

| [26] |

Ellwood M J, Strzepek R F, Strutton P G, et al. 2020. Distinct iron cycling in a Southern Ocean eddy. Nature Communications, 11: 825. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-14464-0

|

| [27] |

Ferrari R, Wunsch C. 2009. Ocean circulation kinetic energy: reservoirs, sources, and sinks. Annual Review of Fluid Mechanics, 41: 253–282. doi: 10.1146/annurev.fluid.40.111406.102139

|

| [28] |

Fox-Kemper B, Adcroft A, Böning CW, et al. 2019. Challenges and prospects in ocean circulation models. Frontiers in Marine Science, 6: 65. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2019.00065

|

| [29] |

Frenger I, Gruber N, Knutti R, et al. 2013. Imprint of Southern Ocean eddies on winds, clouds and rainfall. Nature Geoscience, 6: 608–612. doi: 10.1038/ngeo1863

|

| [30] |

Frenger I, Münnich M, Gruber N. 2018. Imprint of Southern Ocean mesoscale eddies on chlorophyll. Biogeosciences, 15: 4781–4798. doi: 10.5194/bg-15-4781-2018

|

| [31] |

Frenger I, Münnich M, Gruber N, et al. 2015. Southern Ocean eddy phenomenology. Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans, 120(11): 7413–7449. doi: 10.1002/2015JC011047

|

| [32] |

Gent P R. 2011. The Gent–McWilliams parameterization: 20/20 hindsight. Ocean Modelling, 39(1–2): 2–9

|

| [33] |

Gent P R, McWilliams J C. 1990. Isopycnal mixing in ocean circulation models. Journal of Physical Oceanography, 20(1): 150–155. doi: 10.1175/1520-0485(1990)020<0150:IMIOCM>2.0.CO;2

|

| [34] |

Gordon A L, Molinelli E, Baker T. 1978. Large-scale relative dynamic topography of the Southern Ocean. Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans, 83(C6): 3023–3032. doi: 10.1029/JC083iC06p03023

|

| [35] |

Griesel A, Eden C, Koopmann N, et al. 2015. Comparing isopycnal eddy diffusivities in the Southern Ocean with predictions from linear theory. Ocean Modelling, 94: 33–45. doi: 10.1016/j.ocemod.2015.08.001

|

| [36] |

Griesel A, McClean J L, Gille S T, et al. 2014. Eulerian and Lagrangian isopycnal eddy diffusivities in the Southern Ocean of an eddying model. Journal of Physical Oceanography, 44(2): 644–661. doi: 10.1175/JPO-D-13-039.1

|

| [37] |

Grooms I, Kleiber W. 2019. Diagnosing, modeling, and testing a multiplicative stochastic gent-mcwilliams parameterization. Ocean Modelling, 133: 1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.ocemod.2018.10.009

|

| [38] |

Haigh M, Sun Luolin, Shevchenko I, et al. 2020. Tracer-based estimates of eddy-induced diffusivities. Deep-Sea Research Part I: Oceanographic Research Papers, 160: 103264. doi: 10.1016/j.dsr.2020.103264

|

| [39] |

Haller G, Hadjighasem A, Farazmand M, et al. 2016. Defining coherent vortices objectively from the vorticity. Journal of Fluid Mechanics, 795: 136–173. doi: 10.1017/jfm.2016.151

|

| [40] |

Hausmann U, McGillicuddy D J Jr, Marshall J. 2017. Observed mesoscale eddy signatures in Southern Ocean surface mixed-layer depth. Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans, 122(1): 617–635. doi: 10.1002/2016JC012225

|

| [41] |

He Qingyou, Zhan Haigang, Cai Shuqun, et al. 2018. A new assessment of mesoscale eddies in the South China Sea: surface features, three-dimensional structures, and thermohaline transports. Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans, 123(7): 4906–4929. doi: 10.1029/2018JC014054

|

| [42] |

Hu Jianyu, Gan Jianping, Sun Zhenyu, et al. 2011. Observed three-dimensional structure of a cold eddy in the southwestern South China Sea. Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans, 116: C05016

|

| [43] |

Jackett D R, McDougall T J. 1997. A neutral density variable for the world’s oceans. Journal of Physical Oceanography, 27(2): 237–263. doi: 10.1175/1520-0485(1997)027<0237:ANDVFT>2.0.CO;2

|

| [44] |

Ji Jinlin, Dong Changming, Zhang Biao, et al. 2017. An oceanic eddy statistical comparison using multiple observational data in the Kuroshio Extension Region. Acta Oceanologica Sinica, 36(3): 1–7. doi: 10.1007/s13131-016-0882-1

|

| [45] |

Klocker A, Abernathey R. 2014. Global patterns of mesoscale eddy properties and diffusivities. Journal of Physical Oceanography, 44(3): 1030–1046. doi: 10.1175/JPO-D-13-0159.1

|

| [46] |

Klocker A, Marshall D P. 2014. Advection of baroclinic eddies by depth mean flow. Geophysical Research Letters, 41(10): 3517–3521. doi: 10.1002/2014GL060001

|

| [47] |

LaCasce J H, Ferrari R, Marshall J, et al. 2014. Float-derived isopycnal diffusivities in the DIMES experiment. Journal of Physical Oceanography, 44(2): 764–780. doi: 10.1175/JPO-D-13-0175.1

|

| [48] |

Li Qiuyang, Sun Liang, Xu Chi. 2018. The lateral eddy viscosity derived from the decay of oceanic mesoscale eddies. Open Journal of Marine Science, 8: 152–172. doi: 10.4236/ojms.2018.81008

|

| [49] |

Lin Xiayan, Dong Changming, Chen Dake, et al. 2015. Three-dimensional properties of mesoscale eddies in the South China Sea based on eddy-resolving model output. Deep-Sea Research Part I: Oceanographic Research Papers, 99: 46–64. doi: 10.1016/j.dsr.2015.01.007

|

| [50] |

Liu Yu, Dong Changming, Liu Xiaohui, et al. 2017. Antisymmetry of oceanic eddies across the Kuroshio over a shelfbreak. Scientific Reports, 7(1): 6761. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-07059-1

|

| [51] |

Lu Jianhua, Speer K. 2010. Topography, jets, and eddy mixing in the Southern Ocean. Journal of Marine Research, 68(3–4): 479–502

|

| [52] |

Lu Jianhua, Wang Fuchang, Liu Hailong, et al. 2016. Stationary mesoscale eddies, upgradient eddy fluxes, and the anisotropy of eddy diffusivity. Geophysical Research Letters, 43(2): 743–751. doi: 10.1002/2015GL067384

|

| [53] |

Mak J, Maddison J R, Marshall D P. 2016. A new gauge-invariant method for diagnosing eddy diffusivities. Ocean Modelling, 104: 252–268. doi: 10.1016/j.ocemod.2016.06.006

|

| [54] |

Marshall D P, Maddison J R, Berlo P S. 2012. A framework for parameterizing eddy potential vorticity fluxes. Journal of Physical Oceanography, 42(4): 539–557. doi: 10.1175/JPO-D-11-048.1

|

| [55] |

Marshall J, Shuckburgh E, Jones H, et al. 2006. Estimates and implications of surface eddy diffusivity in the Southern Ocean derived from tracer transport. Journal of Physical Oceanography, 36(9): 1806–1821. doi: 10.1175/JPO2949.1

|

| [56] |

Marshall J, Shutts G. 1981. A note on rotational and divergent eddy fluxes. Journal of Physical Oceanography, 11(12): 1677–1680. doi: 10.1175/1520-0485(1981)011<1677:ANORAD>2.0.CO;2

|

| [57] |

Mazloff M R, Heimbach P, Wunsch C. 2010. An eddy-permitting Southern Ocean State Estimate. Journal of Physical Oceanography, 40(5): 880–899. doi: 10.1175/2009JPO4236.1

|

| [58] |

McDougall T J. 1987. Neutral surface. Journal of Physical Oceanography, 17(11): 1950–1964. doi: 10.1175/1520-0485(1987)017<1950:NS>2.0.CO;2

|

| [59] |

McDougall T J, McIntosh P C. 1996. The temporal-residual-mean velocity. Part I: Derivation and the scalar conservation equations. Journal of Physical Oceanography, 26(12): 2653–2665. doi: 10.1175/1520-0485(1996)026<2653:TTRMVP>2.0.CO;2

|

| [60] |

McDougall T J, McIntosh P C. 2001. The temporal-residual-mean velocity. Part II: Isopycnal interpretation and the tracer and momentum equations. Journal of Physical Oceanography, 31(5): 1222–1246. doi: 10.1175/1520-0485(2001)031<1222:TTRMVP>2.0.CO;2

|

| [61] |

Medvedev A S, Greatbatch R J. 2004. On advection and diffusion in the mesosphere and lower thermosphere: The role of rotational fluxes. Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres, 109: D07104

|

| [62] |

Moreau S, Penna A D, Llort J, et al. 2017. Eddy-induced carbon transport across the Antarctic Circumpolar Current. Global Biogeochemical Cycles, 31(9): 1368–1386. doi: 10.1002/2017GB005669

|

| [63] |

Nencioli F, Dong Changming, Dickey T, et al. 2010. A vector geometry-based eddy detection algorithm and its application to a high-resolution numerical model product and high-frequency radar surface velocities in the Southern California Bight. Journal of Atmospheric and Oceanic Technology, 27(3): 564–579. doi: 10.1175/2009JTECHO725.1

|

| [64] |

Ni Qinbiao, Zhai Xiaoming, Wang Guihua, et al. 2020. Random movement of mesoscale eddies in the global ocean. Journal of Physical Oceanography, 50(8): 2341–2357. doi: 10.1175/JPO-D-19-0192.1

|

| [65] |

Nummelin A, Busecke J J M, Haine T W N, et al. 2021. Diagnosing the scale- and space-dependent horizontal eddy diffusivity at the global surface ocean. Journal of Physical Oceanography, 51(2): 279–297. doi: 10.1175/JPO-D-19-0256.1

|

| [66] |

Okubo A. 1970. Horizontal dispersion of floatable particles in the vicinity of velocity singularities such as convergences. Deep-Sea Research and Oceanographic Abstracts, 17(3): 445–454. doi: 10.1016/0011-7471(70)90059-8

|

| [67] |

Orsi A H, Nowlin W D Jr, Whitworth T III. 1993. On the circulation and stratification of the weddell gyre. Deep-Sea Research Part I: Oceanographic Research Papers, 40(1): 169–203. doi: 10.1016/0967-0637(93)90060-G

|

| [68] |

Patel R S, Llort J, Strutton P G, et al. 2020. The biogeochemical structure of Southern Ocean mesoscale eddies. Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans, 125(8): e2020JC016115

|

| [69] |

Poulsen M B, Jochum M, Nuterman R. 2018. Parameterized and resolved Southern Ocean eddy compensation. Ocean Modelling, 124: 1–15. doi: 10.1016/j.ocemod.2018.01.008

|

| [70] |

Pujol M I, Faugère Y, Taburet G, et al. 2016. DUACS DT2014: The new multi-mission altimeter data set reprocessed over 20 years. Ocean Science, 12: 1067–1090. doi: 10.5194/os-12-1067-2016

|

| [71] |

Rhines P B. 2001. Mesoscale eddies. In: Steele M, Turekian K K, Thorpe S A, eds. Encyclopedia of Ocean Science. San Diego, CA, USA: Academic Press, 1982–1992

|

| [72] |

Rohr T, Harrison C, Long M C, et al. 2020. The simulated biological response to Southern Ocean eddies via biological rate modification and physical transport. Global Biogeochemical Cycles, 34(6): e2019GB006385

|

| [73] |

Rypina I I, Kirincich A, Lentz S, et al. 2016. Investigating the eddy diffusivity concept in the coastal ocean. Journal of Physical Oceanography, 46(7): 2201–2218. doi: 10.1175/JPO-D-16-0020.1

|

| [74] |

Sadarjoen I A, Post F H. 2000. Detection, quantification, and tracking of vortices using streamline geometry. Computers & Graphics, 24(3): 333–341

|

| [75] |

Solovev M, Stone P H, Malanotte-Rizzoli P. 2002. Assessment of mesoscale eddy parameterizations for a single-basin coarse-resolution ocean model. Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans, 107(C9): 9-1–9-19

|

| [76] |

Song H, Long M C, Gaube P, et al. 2018. Seasonal variation in the correlation between anomalies of sea level and chlorophyll in the Antarctic Circumpolar Current. Geophysical Research Letters, 45(10): 5011–5019. doi: 10.1029/2017GL076246

|

| [77] |

Stammer D. 1997. Global characteristics of ocean variability estimated from regional TOPEX/POSEIDON altimeter measurements. Journal of Physical Oceanography, 27(8): 1743–1769. doi: 10.1175/1520-0485(1997)027<1743:GCOOVE>2.0.CO;2

|

| [78] |

Stanley Z, Bachman S D, Grooms I. 2020. Vertical structure of ocean mesoscale eddies with implications for parameterizations of tracer transport. Journal of Advances in Modeling Earth Systems, 12(10): e2020MS002151

|

| [79] |

Sun Wenjin, Dong Changming, Tan Wei, et al. 2018. Vertical structure anomalies of oceanic eddies and eddy-induced transports in the South China Sea. Remote Sensing, 10(5): 795. doi: 10.3390/rs10050795

|

| [80] |

Sun Wenjin, Dong Changming, Tan Wei, et al. 2019. Statistical characteristics of cyclonic warm-core eddies and anticyclonic cold-core eddies in the North Pacific based on remote sensing data. Remote Sensing, 11(2): 208. doi: 10.3390/rs11020208

|

| [81] |

Sun Wenjin, Dong Changming, Wang Ruyun, et al. 2017. Vertical structure anomalies of oceanic eddies in the Kuroshio Extension region. Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans, 122(2): 1476–1496. doi: 10.1002/2016JC012226

|

| [82] |

Treguier A M, Held I M, Larichev V D. 1997. Parameterization of quasigeostrophic eddies in primitive equation ocean models. Journal of Physical Oceanography, 27(4): 567–580. doi: 10.1175/1520-0485(1997)027<0567:POQEIP>2.0.CO;2

|

| [83] |

Visbeck M, Marshall J, Haine T, et al. 1997. Specification of eddy transfer coefficients in coarse-resolution ocean circulation models. Journal of Physical Oceanography, 27(3): 381–402. doi: 10.1175/1520-0485(1997)027<0381:SOETCI>2.0.CO;2

|

| [84] |

Vollmer L, Eden C. 2013. A global map of meso-scale eddy diffusivities based on linear stability analysis. Ocean Modelling, 72: 198–209. doi: 10.1016/j.ocemod.2013.09.006

|

| [85] |

Waite A M, Stemmann L, Guidi L, et al. 2016. The wineglass effect shapes particle export to the deep ocean in mesoscale eddies. Geophysical Research Letters, 43(18): 9791–9800. doi: 10.1002/2015GL066463

|

| [86] |

Wang Zifeng, Li Qiuyang, Sun Liang, et al. 2015. The most typical shape of oceanic mesoscale eddies from global satellite sea level observations. Frontiers of Earth Science, 9: 202–208. doi: 10.1007/s11707-014-0478-z

|

| [87] |

Weiss J. 1991. The dynamics of enstrophy transfer in two-dimensional hydrodynamics. Physica D: Nonlinear Phenomena, 48(2–3): 273–294

|

| [88] |

Wolfram P J, Ringler T D, Maltrud M E, et al. 2015. Diagnosing isopycnal diffusivity in an eddying, idealized midlatitude ocean basin via lagrangian, in situ, global, high-performance particle tracking (LIGHT). Journal of Physical Oceanography, 45(8): 2114–2133. doi: 10.1175/JPO-D-14-0260.1

|

| [89] |

Yang Xiao, Xu Guangjun, Liu Yu, et al. 2020. Multi-source data analysis of mesoscale eddies and their effects on surface chlorophyll in the Bay of Bengal. Remote Sensing, 12(21): 3485. doi: 10.3390/rs12213485

|

| [90] |

Ying Y K, Maddison J R, Vanneste J. 2019. Bayesian inference of ocean diffusivity from lagrangian trajectory data. Ocean Modelling, 140: 101401. doi: 10.1016/j.ocemod.2019.101401

|

| [91] |

Zhang Zhiwei, Tian Jiwei, Qiu Bo, et al. 2016. Observed 3D structure, generation, and dissipation of oceanic mesoscale eddies in the South China Sea. Scientific Reports, 6: 24349. doi: 10.1038/srep24349

|

| [92] |

Zhang Zhengguang, Wang Wei, Qiu Bo. 2014. Oceanic mass transport by mesoscale eddies. Science, 345(6194): 322–324. doi: 10.1126/science.1252418

|

| [93] |

Zhang Zhengguang, Zhang Yu, Wang Wei, et al. 2013. Universal structure of mesoscale eddies in the ocean. Geophysical Research Letters, 40(14): 3677–3681. doi: 10.1002/grl.50736

|

| 1. | ZhiYing Liu, GuangHong Liao. Relationship between global ocean mixing and coherent mesoscale eddies. Deep Sea Research Part I: Oceanographic Research Papers, 2023, 197: 104067. doi:10.1016/j.dsr.2023.104067 | |

| 2. | Xiaoqi Ding, Hao Shen, Jialong Sun, et al. Effects of an eastward shift in the Agulhas retroflection region on chlorophyll-a bloom on its south flank. PLOS ONE, 2023, 18(3): e0281766. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0281766 | |

| 3. | Wenjin Sun, Mengxuan An, Jishan Liu, et al. Comparative analysis of four types of mesoscale eddies in the North Pacific Subtropical Countercurrent region - part II seasonal variation. Frontiers in Marine Science, 2023, 10 doi:10.3389/fmars.2023.1121731 | |

| 4. | Guangchuang Zhang, Ru Chen, Laifang Li, et al. Global trends in surface eddy mixing from satellite altimetry. Frontiers in Marine Science, 2023, 10 doi:10.3389/fmars.2023.1157049 | |

| 5. | Wenjin Sun, Mengxuan An, Jie Liu, et al. Comparative analysis of four types of mesoscale eddies in the Kuroshio-Oyashio extension region. Frontiers in Marine Science, 2022, 9 doi:10.3389/fmars.2022.984244 | |

| 6. | Li Zhang, Chengyan Liu, Wenjin Sun, et al. Modeling Mesoscale Eddies Generated Over the Continental Slope, East Antarctica. Frontiers in Earth Science, 2022, 10 doi:10.3389/feart.2022.916398 | |

| 7. | Mengxuan An, Jie Liu, Jishan Liu, et al. Comparative analysis of four types of mesoscale eddies in the north pacific subtropical countercurrent region – part I spatial characteristics. Frontiers in Marine Science, 2022, 9 doi:10.3389/fmars.2022.1004300 |