| Citation: | Xiaomin Chang, Wenhao Liu, Guangyu Zuo, Yinke Dou, Yan Li. Research on ultrasonic-based investigation of mechanical properties of ice[J]. Acta Oceanologica Sinica, 2021, 40(10): 97-105. doi: 10.1007/s13131-021-1890-3 |

Arctic sea ice area and thickness have declined dramatically in recent years (Stroeve et al., 2012; Laxon et al., 2013; Lei et al., 2014) and has attracted much attention (Arrigo et al., 2008; Comiso, 2012; Day et al., 2012). The shrinking and thinning of Arctic sea ice have made greater accessibility for shipping in Arctic Ocean such as the Northeast Passage (Lei et al., 2015; Smith and Stephenson, 2013). The most important sea ice parameters for shipping are concentration, thickness and type (Zuo et al., 2018b). As a special multiphase mixture, sea ice contains solid ice, air bubbles and liquid brine bubbles. The mechanical properties of sea ice are also very important for polar region operations in cold regions (Kjerstad et al., 2015; Montewka et al., 2015; Wang et al., 2018). Thus, the development of polar navigation requires more research of the mechanics of sea ice.

In previous studies, some mechanical parameters of Arctic sea ice, such as tensile strength (Kuehn et al., 1990), flexural strength (Saeki et al., 1981), failure envelope (Schulson et al., 2006), and uniaxial compression strength (Chen and Lee, 1988; Sinha, 1984, 1986), have been reported. However, more detailed researches are still needed because of the lack of information and rapid changes of Arctic ice (Smith and Stephenson, 2013).

Weeks and Ackley (1986) elaborated on the internal structure of sea ice, its development and how it affected the bulk properties of the ice. The mechanical properties of ice bending (Svec et al., 1985; Gow et al., 1978; Gow and Ueda, 1989) and compression (Daley et al., 1998) have been studied. Marchenko et al. (2014) demonstrated significant stress concentrations near the edges and close to the roots of simulated beam with numerical simulations. Wang et al. (2016) used in-situ cantilever beam method to determine the bending strength and elastic modulus of the ice layer. And the results showed that as the ice temperature decreased, the bending strength and elastic modulus presented an increasing trend. Moslet (2007) carried out tests of uniaxial compression strength of columnar sea ice and found that there is a strong relationship between Young’s modulus and porosity. An increasing number of researchers have studied the strength and ridging of sea ice using models (Flato and Hibler, 1995; Lipscomb et al., 2007).

Measurements of sea ice mechanical properties can be found in several studies (e.g., Forsström et al., 2011; Frantz et al., 2019; Ukita et al., 2000; Huang et al., 2016), such as ice core measurement based on the mass/volume method, displacement (submersion) and specific gravity (Timco and Frederking, 1996). However, ice core method may have measurement errors caused by brine drainage (Hutchings et al., 2015) and the volume measurement of the ice sample (Pustogvar and Kulyakhtin, 2016). Most studies on the structure and distribution of sea ice are based on meteorological data and climate models (Flato and Hibler, 1995; Lipscomb et al., 2007; Sun and Eisenman, 2021). To the authors’ best knowledge, there have been only a few studies on the automatic measurement technology of ice mechanical properties. Considering the cost and inconvenience of field tests in polar region (Zuo et al., 2018a), a low cost and automatic measurement method of mechanical properties of ice is needed.

Ultrasonic waves have high penetrating power as well as directivity, such as the detection of internal structures of composite plates and biological tissues (Wang et al., 2002; Ma et al., 2011), as well as detection of metal forgings and welding seams of defects (Li et al., 2007). Recently, numerous studies have been conducted on the detection of porous materials by ultrasonic waves. Sea ice is composed of pure ice crystals, brine, solid salt, and air bubbles, which can be regarded as a special composite material. Therefore, ultrasonic wave is feasible to test the properties of ice for the similarities between sea ice and composite material structures.

In this study, four parameters (Young’s modulus, bulk modulus, shear modulus, Poisson’s factor) are selected as indicators to measure the mechanical properties of ice and the corresponding mechanical properties of ice can be obtained by measuring these parameters. Young’s modulus is a physical quantity that represents the resistance of solid materials to deformation. It is the ratio of tensile stress to tensile strain in the elastic range of an object. When the material is under a certain stress, the larger value means the smaller the deformation in the stress direction. Bulk modulus is a ratio of the increasing value of the pressure on the object to the changing value of the per unit volume of the object in the elastic range. The higher value of bulk modulus may represent the smaller decrease of the volume of the material when the pressure is increased. Shear modulus is a ratio of shear stress and strain in the range of elastic deformation. The higher value of shear modulus represents the stronger rigidity of the material. Poisson’s factor is a ratio of transverse and longitudinal deformation of a material when it is compressed or stretched. It is a dimensionless physical quantity. There is a positive correlation between the transverse deformation and Poisson’s factor when the longitudinal deformation is constant.

The mechanical properties of freshwater ice were studied using an ultrasonic system in this study. An automatic observation method for mechanical properties of sea ice based on ultrasonic wave was proposed to solve the problem of low efficiency of ice core collection and realize the seasonal observation of sea ice mechanical properties. The principle of measuring mechanical properties of ice simples was studied and proposed. Key parameters of ultrasonic penetrating ice simples can be obtained using the designed system to analyze on the trend of ultrasonic parameters and ice mechanical parameters between 0°C and −30°C. The relationship between mechanical properties of ice and ultrasonic parameters were proposed and can provide guidance for future design and research of trans-Arctic navigation.

The following sections of this paper consist of three parts: the methods of measuring mechanical properties of ice simples and parameters of ultrasound penetrating ice simples, the analysis about change of ultrasonic parameters and ice mechanical parameters, and conclusions about the relation of mechanical properties of ice simples and ultrasonic parameters.

Autonomous, long-term measurements of ice physical and mechanical properties are of great significance to the monitoring of sea ice in Arctic. Ultrasound-based remote monitoring technology can provide new possibilities. These measurements would complement sea ice observation data by providing measurements of ice physical and mechanical properties of ice in polar regions.

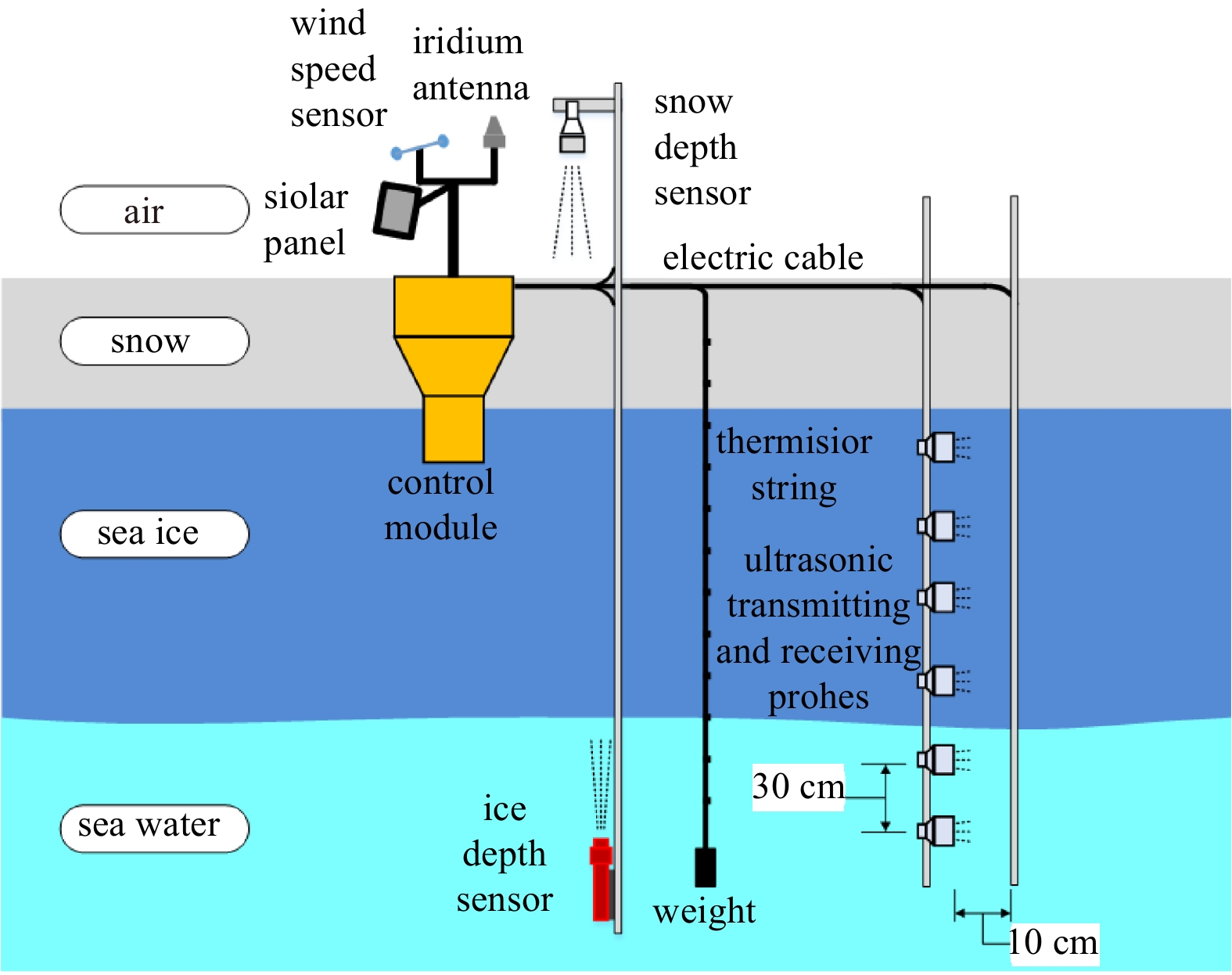

Multiple pairs of ultrasonic transmitters and receivers were used in this system to detect ice at different depths. To minimize the damaging of the ice surface, ultrasonic transmitters and receivers would be deployed into one ice auger hole. Sensors such as thermistor string, sonar altimeter, snow depth sensor and GPS were used to realize the observation of snow and ice conditions and basic information of ice environment in polar regions.

A potential ultrasonic system for sea ice mechanical parameter observation was proposed and designed. This system was equipped with an ultrasonic exciter connecting to ultrasonic probes (BH-50, Shantou Ultrasound, Shantou, China), a buoy containing a controller (TUT430-S1, Taiyuan University of Technology, Taiyuan, China), a battery unit and a satellite modem (Iridium 9523, McLean, VA, USA). Thermistor string, sonar altimeter (PSA-916, Teledyne Benthos, North Falmouth, MA, USA), snow depth sensor (SR50A, Campbell, Camden, NJ, USA) and GPS (AG332GPS, Trimble, Arlington, VA, USA) were assembled to measure sea ice mass balance, sea ice temperature and can be controlled by the controller which was designed by Taiyuan University of Technology. Ultrasonic probes were lowered through a 3-cm auger hole drilled through snow and sea ice. Snow depth and ice thickness are measured using ancillary sensors in conjunction with the thermistor string deployed in another auger hole. This system adopts the structure shown in Fig. 1.

This system was equipped with 6–8 pairs of ultrasonic transmitting and receiving probes fixed on the metal bracket from top to bottom. The vertical distance between probes was 30 cm. The controller and remote transmission module were installed in the buoy on ice and sealed with epoxy resin insulation material. The circuit block diagram is shown in Fig. 2. A microprogrammed controller (MSP430F5438A, Texas Instruments, Dallas, TX, USA) was used to control the sinusoidal signal generator to generate sinusoidal pulse signals with a frequency of 1 MHz. After the analog multiplex switch is turned on, the sinusoidal signal can be sent to the ultrasonic emitting probe. Ultrasonic waves are received by the receiving probe after penetrating air, sea ice, or seawater. The received signals are processed by a signal processing circuit, such as rectification detection and filtering, and are sampled and stored under the control of single-chip microcomputer. According to the correlation between the ultrasonic signal and ice mechanical parameters (including Young’s modulus, shear modulus and bulk modulus), the real-time detection of sea ice can be realized through the processing of field signals.

The system was also equipped with the sea ice temperature string for observing sea ice temperature profile from air to ice to provide data for the measurement of mechanical parameters (Young’s modulus, shear modulus and bulk modulus). The controller can also control the remote transmission module to realize remote transmission of data and programs between the system and the shore-based site. The system was powered by the cryogenic battery.

In this study, freshwater ice sample and sea ice sample are used in this study to measure mechanical properties. The freshwater ice is pure and structure of freshwater ice is simple, which can better verify the feasibility of measurement of ice mechanical parameters based on ultrasonic. Sea ice samples used in the laboratory were prepared by freezing the seawater. Compared with sea ice acquired in-situ in polar regions, sea ice samples made in the laboratory have less porosity and greater density. The data and results obtained through experiments in this study can verify the feasibility of the mechanical properties of sea ice measured based on ultrasonic. And the system can realize in-situ measurement of sea ice mechanical parameters.

The basic formula for calculating the mechanical properties of ice samples (Wang et al., 1974; Guo et al., 2016) can be described as follows.

Ice shear modulus G:

| $$G = \rho V_P^2.$$ | (1) |

Ice bulk modulus K:

| $$K = \rho \left(V_P^2 - \frac{4}{3}V_S^2\right).$$ | (2) |

Ice Young’s modulus E:

| $$E = \frac{{\rho V_S^2}}{{V_P^2 - V_S^2}}(3V_P^2 - 4V_S^2),$$ | (3) |

where ρ is the density of sea ice, VP is the velocity of the longitudinal wave and VS is the velocity of the shear wave.

The measurement of ice mechanical parameters mainly depends on traditional mechanical tests, such as the uniaxial compression test and bending test. The river ice shear modulus was tested with value between 0.81 GPa and 2.31 GPa (Yu et al., 2009) and the fresh ice elastic modulus was tested with value between 3.62 GPa and 6.71 GPa (Wang et al., 2016). Guo and Meng (2015) performed a series of tests to obtain the stress-strain curve and obtained the bulk modulus of the river ice ranging from 0.5 GPa to 0.9 GPa.

These mechanical parameters calculated by ultrasound are larger than those in the references above, but the changing trend with temperature is similar. The difference in mechanical modulus between ultrasonic measurement and traditional test mainly comes from the error of density measurement, and the formula for calculating the mechanical properties of ice samples needs to be updated based on the ice properties.

In this study, the density measurement of ice samples was performed using the mass-volume technique. Using this method, the ice sample shown in Fig. 3 was cut from the ice cube made in the laboratory, and then trimmed to a standard cube with a volume of approximately 10 cm×10 cm×10 cm. The sample dimensions were measured and the volume (V) of each sample was calculated. The sample was weighed to give its mass (M). The density of the ice (ρ) can be calculated by:

| $$\rho = \frac{M}{V},$$ | (4) |

where ρ is the ice sample density, V is the volume of the samples, and M is the mass of the ice samples.

The measurement processes were performed at a low temperature, in which the air temperature was lower than −15°C to avoid brine drainage from the sample.

The velocities of the shear wave and longitudinal wave were obtained by the echo method. The velocity of ultrasound is calculated by the time difference between echoes and the traveling distance of the ultrasound. The upper and lower surfaces of the ice samples were polished in a low-temperature environment, and the thickness of the ice samples was measured with a vernier caliper (accuracy of 0.01 mm). The crossing distance of ultrasound can be recorded as L.

The primary and secondary echoes of the ultrasonic signal were obtained by the test of ultrasonic waves penetrating the sea ice (Fig. 4). After the ultrasound penetrates the sea ice to the bottom and returns, the time difference can be obtained by calculating between the first and the second echoes.

The velocities of the shear wave and longitudinal wave (v) can be calculated by:

| $$v = \frac{L}{{2T}},$$ | (5) |

where v is the velocity of the shear wave and longitudinal wave, L is the distance between the upper and lower surfaces of the ice samples, and T is the time difference between the first and the second echoes.

To investigate the relationship between ultrasonic parameters (such as sound velocity, peak-to-peak value and attenuation) and the physical and mechanical properties of sea ice, an experimental system was designed. This system uses ultrasonic equipment to measure the parameters of ultrasonic waves passing through the ice, such as propagation velocity, peak-to-peak value, and attenuation. These parameters are combined with the measured physical parameters of the ice, and the mechanical parameters of ice can be calculated using the empirical formula (Wang et al., 1974; Guo et al., 2016). By fitting the measurement data, the correlation between the mechanical parameters of the ice and the ice temperature can be obtained.

The system included an ultrasonic system (RAM-5000, Ritec, Simi Valley, CA, USA), two temperature measuring probes (PT1000), an ultrasonic transmitting and receiving probe (BH-50, Shantou Ultrasound, Shantou, China), an oscilloscope (DSOX3034T, Keysight, Santa Clara, CA, USA), and a low-temperature freezer (MDF-60V50, Zhongkeduling, Hefei, China).

The centre frequency of the pulse signal used in this study was 1 MHz. A 50-Ω high-energy matching resistor and attenuator were connected to the ultrasonic system in case of failure by a short circuit. The attenuator’s function is to make the received ultrasonic signal curve smoother to reduce the glitch of the ultrasonic signal. The ultrasonic probes are a pair of 1-MHz main frequency ultrasonic longitudinal wave straight probes, and transverse probes are straight probes. Figure 5 shows an experimental ultrasonic testing system.

Initially, seawater with a salinity of 3‰ was placed in a plastic bucket with a capacity of 2 L. The ultrasonic probe and temperature sensor were placed in the seawater. The ultrasonic probes were fixed on a rigid slat with a distance of 2.5 cm. The probe emitting surface was coated with a coupler and wrapped with a plastic film. The temperature sensor was fixed in addition to ultrasonic probe.

The temperature of the freezer was set directly to −30°C. After water was completely frozen, the ice sample temperature was gradually adjusted at intervals of 5°C. When the temperature of ice samples reached the target temperature and remained stable, the temperature and ultrasonic wave velocity were recorded, and the ice was sampled for density measurement using the density-volume method.

This experiment included the process of gradually freezing water into ice and gradually warming the ice. The purpose of comparing the temperature rising and falling processes is to determine whether the change in temperature will affect the mechanical properties of ice. From the experimental results analysis, the slight difference in the data was mainly caused by the measurement error. It can be considered that the influence of different processes on the mechanical parameters of ice is negligible.

According to the probe frequency, the ultrasonic pulse transmission frequency was set to 1 MHz, and the quality of the received signal was observed on the oscilloscope until the received signal was clear. The speed of sound can be calculated by recording the ultrasonic propagation time and probe distance. The temperature values and ice salinity were recorded. The ultrasonic signal time-domain graph can be saved in the CSV format.

The original data can be read to obtain the original image of the preserved ultrasonic signal. The effective ultrasonic signal was intercepted, as shown in Fig. 6.

A fast Fourier transform was used to obtain a spectrogram of the ultrasonic signal, whose abscissa is the centre frequency of the ultrasonic probe and whose ordinate is the amplitude of the signal, as shown in Fig. 7.

When the freshwater ice sample temperature changed from 0°C to −30°C, the temperature and ultrasonic wave velocity were recorded, respectively. The ultrasonic speed change versus ice temperature is shown in Fig. 8.

It can be seen from Fig. 8 that the ultrasonic shear wave velocity and the longitudinal wave velocity both increased with the decrease of temperature. When the temperature of freshwater ice sample decreased from 0°C to −30°C, the shear wave velocity varied from 1 564.196 m/s to 1 668.892 m/s, and the longitudinal wave velocity varied from 2 785.564 m/s to 2 957.602 m/s. At the same temperature, the longitudinal wave velocity was approximately 1.77 times larger than that of the transverse wave velocity. The law of the mechanical parameters of the freshwater ice with temperature can be obtained by substituting the ultrasonic shear wave velocity and the longitudinal wave velocity into the empirical formula. Curve fitting was performed, and the fitting correlation coefficient was 0.998. The change in the mechanical parameters of the freshwater ice sample versus ice temperature is shown in Fig. 9.

As shown in Fig. 9, the ice shear modulus gradually increased from 2.173 GPa to 2.48 GPa with a mean of 2.33 GPa and a standard deviation of 0.11 as the freshwater ice sample temperature decreased from 0°C to −30°C. The ice bulk modulus increased from 3.85 GPa to 4.566 GPa with a mean of 4.24 GPa and a standard deviation of 0.20, and the Young’s modulus values of the ice samples increased from 5.327 GPa to 6.264 GPa with a mean of 5.89 GPa and a standard deviation of 0.27. The Poisson’s ratio increased from 0.219 to 0.260 with a mean of 0.240 and a standard deviation of 0.012 (Fig. 10).

The mechanical modulus of ice represents the difficulty of ice elastic deformation, which means that under certain stresses, the larger the modulus, the smaller the elastic deformation. When the same strain occurs, the greater the mechanical modulus, the greater the stress that needs to be applied to the material. The mechanical modulus represents the stiffness of the ice as an elastic material.

As a special material, the mechanical properties of ice are affected by hydrogen bonds in the molecule and the geometry of the lattice (Lu et al., 2002). As the ice temperature decreased, the atomic displacement in the ice crystal space grid became more difficult, the distance between atoms became smaller, the bonding force of atoms became larger, the polar bonds and hydrogen bonds became more stable and the crystal lattice becomes tighter. As a result, the elasticity of the ice become more prominent, the stiffness of ice becomes more difficult, and the ability to resist lateral and axial deformation is enhanced.

When the ice sample temperature changes from −30°C to 0°C, the trend of the ultrasonic shear wave velocity and longitudinal wave velocity can be obtained. The waveform of the ultrasonic transverse wave velocity was 0.997, as shown in Fig. 11. Furthermore, the mechanical parameters of the freshwater ice can be obtained, as shown in Fig. 12.

The ultrasonic shear wave velocity and the longitudinal wave velocity decreased with an increase in temperature during the process of the freshwater ice sample temperature changing from −30°C to 0°C. The value of ultrasonic shear wave velocity gradually decreased from 1 670.726 m/s to 1 569.171 m/s, and the value of ultrasonic longitudinal wave velocity gradually decreased from 2 941.228 m/s to 2 620.411 m/s. The value of Young’s modulus gradually reduced from 6.259 GPa to 5.156 GPa with a mean of 5.67 GPa and a standard deviation of 0.31, the value of shear modulus gradually reduced from 2.48 GPa to 2.112 GPa with a mean of 2.27 GPa and a standard deviation of 0.10, and the value of bulk modulus gradually reduced from 4.379 GPa to 3.074 GPa with a mean of 3.65 GPa and a standard deviation of 0.38. The Poisson’s ratio decreases from 0.258 to 0.219 with a mean of 0.239 and a standard deviation of 0.012 (Fig. 13).

As the ice temperature increased, the atomic displacement in the ice crystal space grid becomes easier, the distance between atoms became larger, the bonding force of atoms became weaker, the polar bonds and hydrogen bonds were less stable and the crystal lattice became looser. As a result, the plasticity of the ice becomes more prominent and the stiffness of ice becomes weaker. The ability to resist lateral and axial deformations decreased.

The mechanical properties of the ice sample (including Young’s modulus, the shear modulus and bulk modulus) decreased with increasing temperature, which was consistent with the results in Section 4.1. At the same temperature, the difference of values of the two processes was not significant.

The seawater used in the experiment was the self-configuration seawater. Sea salt and freshwater were configured at a certain ratio. Seawater with different salinities can be obtained. The seawater salinity used in this study was 13.7 .

The ultrasonic parameters penetrating the sea ice were measured, and the shear wave velocity and longitudinal wave velocity data of the measured sea ice sample were interpolated to obtain the curve of ultrasonic velocity and sea ice sample temperature (Fig. 14).

As the sea ice temperature decreases, the wave velocity rose and fell without obvious regularity. The shear wave velocity varied from 1 881.156 m/s to 2 253.35 m/s when the temperature decreased from 0°C to −20°C and continues to grow when the temperature was lower than −20°C. The longitudinal wave velocity rapidly increased from 2 449.781 m/s to 2 784.534 m/s when the sea ice temperature decreased from 0°C to −10°C. When the sea ice temperature was lower than −10°C, the longitudinal wave velocity basically remained unchanged and the velocity gradually increased from 2 784.124 m/s to 2 903.854 m/s. The propagation speed of ultrasonic shear waves in sea ice was faster than that in freshwater ice, but the velocity of ultrasonic longitudinal waves in sea ice was slower than that in freshwater ice at the same temperature. The relationship between sea ice ultrasonic mechanical parameters of sea ice and ice sample temperature is shown in Fig. 15.

It can be seen from Fig. 15 that when the sea ice temperature decreased from 0°C to −30°C, the sea ice mechanical parameters (shear modulus, bulk modulus and Young’s modulus) increased. At the same temperature, the Young’s modulus had the largest value and the bulk modulus had the smallest value. The value of sea ice shear modulus varied from 2.927 GPa to 4.374 GPa and it continues to decrease when the temperature was lower than −20°C because the shear wave velocity changing trend had a major influence on the shear modulus calculation. The value of sea ice shear modulus was larger than that of freshwater ice, indicating that sea ice had stronger shear resistance than freshwater ice at the same temperature and it was less prone to shear deformation.

The bulk modulus of sea ice varied from 1.211 GPa to 3.089 GPa, which was smaller than that of freshwater ice samples, indicating that freshwater ice had stronger compression resistance than sea ice at the same temperature that ice was less prone to compression deformation. It kept falling when the temperature was lower than −20°C because the shear wave velocity changing trend had a major influence on the bulk modulus calculation.

The value of the Young’s modulus of sea ice varied from 3.793 GPa to 7.492 GPa, which was larger than that of freshwater ice, indicating that temperature had a greater effect on the Young’s modulus of sea ice. As the temperature decreased, the axial deformation of the sea ice increased.

This paper introduces an ultrasonic-based method to detect the parameters of mechanical properties of ice. An ultrasonic test system was established to measure freshwater ice and sea ice samples as the temperature gradually decreased from 0°C to −30°C and then gradually increased from −30°C to 0°C. The following conclusions were drawn from the experimental data.

During the process of changing the freshwater ice sample temperature from 0°C to −30°C, the ultrasonic transverse wave velocity and the longitudinal wave velocity increased with the decrease in temperature. At the same temperature, the longitudinal wave velocity is approximately 1.77 times larger than that of the transverse wave velocity. The mechanical parameters of the ice increase with the decrease of temperature: the shear modulus of the ice samples varies from 2.098 GPa to 2.473 GPa, and the ice bulk modulus values range from 3.85 GPa to 4.566 GPa, and the Young’s modulus values range from 5.327 GPa to 6.264 GPa. The Poisson’s ratio increases from 0.219 to 0.260. These data are consistent with the data in the literature (Guo et al., 2016).

During the process of changing the temperature of a freshwater ice sample from −30°C to 0°C, the ultrasonic transverse wave velocity, longitudinal wave velocity and mechanical properties of the ice sample decrease with an increase in temperature, which is similar to the decrease in ice temperature from 0°C to −30°C. The value of Young’s modulus gradually reduces from 6.259 GPa to 5.156 GPa, the value of shear modulus gradually reduces from 2.48 GPa to 2.112 GPa, and the value of bulk modulus gradually reduces from 4.379 GPa to 3.074 GPa. The Poisson’s ratio decreases from 0.258 to 0.219. At the same temperature, the values of the parameters during the temperature rising and dropping process are close.

During the process of the sea ice sample temperature decreasing from 0°C to −30°C, the wave velocities of the shear wave and longitudinal wave decrease. The mechanical parameters increased with a decrease in temperature. The shear modulus varied from 2.927 GPa to 4.374 GPa. The bulk modulus varies from 1.211 GPa to 3.089 GPa and the Young’s modulus varies from 3.793 GPa to 7.492 GPa.

These mechanical parameters calculated by ultrasound are larger than those calculated using a material testing machine, but the trend with temperature is similar. The difference in mechanical modulus between ultrasonic measurement and traditional test mainly comes from the error of measurement of ice density and ultrasound velocity, and the formula for calculating the mechanical properties of ice samples needs to be updated based on the ice properties.

The attenuation characteristics of ultrasonic waves on ice were obvious. Through an in-depth comparative study, the dispersion characteristics and attenuation characteristics of ultrasonic waves propagating in river ice, lake ice and sea ice can be obtained. Thus, ultrasonic signal amplitudes can be obtained at different temperatures and densities. The attenuation characteristics of ultrasonic waves propagating in river ice, lake ice and sea ice can be obtained, and the attenuation coefficient of ultrasonic waves in ice can be obtained. According to the sound velocity law of ultrasonic waves propagating in river ice, lake ice and sea ice, the mechanical parameters of river ice, lake ice and sea ice allow for obtaining the Young’s modulus, Poisson’s ratio, the shear modulus and the bulk modulus, and can then be used to determine the density of the ice. Therefore, the relationship between the attenuation coefficient of ultrasonic waves in ice and the density of ice can be obtained at different temperatures and densities. The ice density detection sensor and its system for designing optimal parameters are being studied. By evaluating the relationship between ice density and the attenuation coefficient of ultrasonic waves, direct judegment of ice density can be realized. This research is innovative.

Our future work will be to achieve automatic observation of sea ice mechanics parameters through ultrasonic testing, which can be applied to ice conditions detection and the acquisition of environmental parameters of the Arctic Ocean and Antarctica.

Peng Lu provided valuable advice on the idea for the study. We thank Yan Li, Dalei Liu, Jianlong Liu, and Yang Ou for their assistance.

| [1] |

Arrigo K R, van Dijken G, Pabi S. 2008. Impact of a shrinking Arctic ice cover on marine primary production. Geophysical Research Letters, 35(19): L19603. doi: 10.1029/2008GL035028

|

| [2] |

Chen A C T, Lee J. 1988. Large-scale ice strength tests at slow strain rates. Journal of Offshore Mechanics and Arctic Engineering, 110(3): 302–306. doi: 10.1115/1.3257066

|

| [3] |

Comiso J C. 2012. Large decadal decline of the arctic multiyear ice cover. Journal of Climate, 25(4): 1176–1193. doi: 10.1175/JCLI-D-11-00113.1

|

| [4] |

Daley C, Tuhkuri J, Riska K. 1998. The role of discrete failures in local ice loads. Cold Regions Science and Technology, 27(3): 197–211. doi: 10.1016/S0165-232X(98)00007-X

|

| [5] |

Day J J, Hargreaves J C, Annan J D, et al. 2012. Sources of multi-decadal variability in Arctic sea ice extent. Environmental Research Letters, 7(3): 034011. doi: 10.1088/1748-9326/7/3/034011

|

| [6] |

Flato G M, Hibler W D. 1995. Ridging and strength in modeling the thickness distribution of Arctic sea ice. Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans, 100(C9): 18611–18626. doi: 10.1029/95JC02091

|

| [7] |

Forsström S, Gerland S, Pedersen C A. 2011. Thickness and density of snow-covered sea ice and hydrostatic equilibrium assumption from in situ measurements in Fram Strait, the Barents Sea and the Svalbard coast. Annals of Glaciology, 52(57): 261–270. doi: 10.3189/172756411795931598

|

| [8] |

Frantz C M, Light B, Farley S M, et al. 2019. Physical and optical characteristics of heavily melted “rotten” Arctic sea ice. The Cryosphere, 13(3): 775–793. doi: 10.5194/tc-13-775-2019

|

| [9] |

Gow A J, Ueda H T. 1989. Structure and temperature dependence of the flexural properties of laboratory freshwater ice sheets. Cold Regions Science and Technology, 16(3): 249–270. doi: 10.1016/0165-232X(89)90026-8

|

| [10] |

Gow A J, Ueda H T, Ricard J A. 1978. Flexural strength of ice on temperate lakes: comparative tests of large cantilever and simply supported beams. Hanover, Germany: Cold Regions Research and Engineering Laboratory, 1−20

|

| [11] |

Guo Yao, Li Gang, Jia Chengyan, et al. 2016. Study of ultrasonic test in the measurements of mechanical properties of ice. Chinese Journal of Polar Research (in Chinese), 28(1): 152–157

|

| [12] |

Guo Yingkui, Meng Wenyuan. 2015. Experimental investigations on mechanical properties of ice. Journal of North China University of Water Resources and Electric Power (Natural Science Edition) (in Chinese), 36(3): 40–43

|

| [13] |

Huang Wenfeng, Lei Ruibo, Han Hongwei, et al. 2016. Physical structures and interior melt of the central Arctic sea ice/snow in summer 2012. Cold Regions Science and Technology, 124: 127–137. doi: 10.1016/j.coldregions.2016.01.005

|

| [14] |

Hutchings J K, Heil P, Lecomte O, et al. 2015. Comparing methods of measuring sea-ice density in the East Antarctic. Annals of Glaciology, 56(69): 77–82. doi: 10.3189/2015AoG69A814

|

| [15] |

Kjerstad Ø K, Metrikin I, Løset S, et al. 2015. Experimental and phenomenological investigation of dynamic positioning in managed ice. Cold Regions Science and Technology, 111: 67–79. doi: 10.1016/j.coldregions.2014.11.015

|

| [16] |

Kuehn G A, Lee R W, Nixon W A, et al. 1990. The structure and tensile behavior of first-year sea ice and laboratory grown saline ice. Journal of Offshore Mechanics and Arctic Engineering, 112(4): 357–363. doi: 10.1115/1.2919878

|

| [17] |

Laxon S W, Giles K A, Ridout A L, et al. 2013. CryoSat-2 estimates of Arctic sea ice thickness and volume. Geophysical Research Letters, 40(4): 732–737. doi: 10.1002/grl.50193

|

| [18] |

Lei Ruibo, Li Na, Heil P, et al. 2014. Multiyear sea ice thermal regimes and oceanic heat flux derived from an ice mass balance buoy in the Arctic Ocean. Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans, 119(1): 537–547. doi: 10.1002/2012JC008731

|

| [19] |

Lei Ruibo, Xie Hongjie, Wang Jia, et al. 2015. Changes in sea ice conditions along the Arctic Northeast Passage from 1979 to 2012. Cold Regions Science and Technology, 119: 132–144. doi: 10.1016/j.coldregions.2015.08.004

|

| [20] |

Li Junwen, Momono T, Fu Ying. 2007. Effect of ultrasonic power on density and refinement in aluminum ingot. China Foundry (in Chinese), 56(2): 152–154, 157

|

| [21] |

Lipscomb W H, Hunke E C, Maslowski W, et al. 2007. Ridging, strength, and stability in high-resolution sea ice models. Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans, 112(C3): C03S91

|

| [22] |

Lu Qinnian, Tang Aiping, Zhong Nanping. 2002. Calculating method of river ice loads on piers (I): the mechanical behavior test of river ice. Journal of Natural Disasters (in Chinese), 11(2): 75–79

|

| [23] |

Ma Lang, Guo Jianzhong, Liu Bo. 2011. Study on the frequency property of ultrasonic scatterer in soft tissue. Piezoelectrics & Acoustooptics (in Chinese), 33(5): 761–763, 767

|

| [24] |

Marchenko A, Karulin E, Chistyakov P, et al. 2014. Three dimensional fracture effects in tests with cantilever and fixed ends beams. In: Proceedings of the 22nd IAHR International Symposium on Ice. Singapore: International Association for Hydro-Environment Engineering and Research (IAHR), 249–256

|

| [25] |

Montewka J, Goerlandt F, Kujala P, et al. 2015. Towards probabilistic models for the prediction of a ship performance in dynamic ice. Cold Regions Science and Technology, 112: 14–28. doi: 10.1016/j.coldregions.2014.12.009

|

| [26] |

Moslet P O. 2007. Field testing of uniaxial compression strength of columnar sea ice. Cold Regions Science and Technology, 48(1): 1–14. doi: 10.1016/j.coldregions.2006.08.025

|

| [27] |

Pustogvar A, Kulyakhtin A. 2016. Sea ice density measurements. Methods and uncertainties. Cold Regions Science and Technology, 131: 46–52. doi: 10.1016/j.coldregions.2016.09.001

|

| [28] |

Saeki H, Ozaki A, Kubo Y. 1981. Experimental study on flexural strength and elastic modulus of sea ice. In: POAC 81: Proceedings of 6th International Conference on Port and Ocean Engineering under Arctic Conditions. Quebec City, Quebec, Canada: Laval University, 1: 536–547

|

| [29] |

Schulson E M, Fortt A L, Iliescu D, et al. 2006. Failure envelope of first-year Arctic sea ice: the role of friction in compressive fracture. Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans, 111(C11): C11S25

|

| [30] |

Sinha N K. 1984. Uniaxial compressive strength of first-year and multi-year sea ice. Canadian Journal of Civil Engineering, 11(1): 82–91. doi: 10.1139/l84-010

|

| [31] |

Sinha N K. 1986. Young Arctic frazil sea ice: field and laboratory strength tests. Journal of Materials Science, 21(5): 1533–1546. doi: 10.1007/BF01114706

|

| [32] |

Smith L C, Stephenson S R. 2013. New Trans-Arctic shipping routes navigable by midcentury. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 110(13): E1191–E1195. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1214212110

|

| [33] |

Stroeve J C, Kattsov V, Barrett A, et al. 2012. Trends in Arctic sea ice extent from CMIP5, CMIP3 and observations. Geophysical Research Letters, 39(16): L16502

|

| [34] |

Sun S T, Eisenman I. 2021. Observed Antarctic sea ice expansion reproduced in a climate model after correcting biases in sea ice drift velocity. Nature Communications, 12(1): 1060. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-21412-z

|

| [35] |

Svec O J, Thompson J C, Frederking R M W. 1985. Stress concentrations in the root of an ice cover cantilever: model tests and theory. Cold Regions Science and Technology, 11(1): 63–73. doi: 10.1016/0165-232X(85)90007-2

|

| [36] |

Timco G W, Frederking R M W. 1996. A review of sea ice density. Cold Regions Science and Technology, 24(1): 1–6. doi: 10.1016/0165-232X(95)00007-X

|

| [37] |

Ukita J, Kawamura T, Tanaka N, et al. 2000. Physical and stable isotopic properties and growth processes of sea ice collected in the southern Sea of Okhotsk. Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans, 105(C9): 22083–22093. doi: 10.1029/1999JC000013

|

| [38] |

Wang Jiankang, Cao Xiaowei, Wang Qingkai, et al. 2016. Experimental relationship between flexural strength, elastic modulus of ice sheet and equivalent ice temperature. South-to-North Water Transfers and Water Science & Technology (in Chinese), 14(6): 75–80

|

| [39] |

Wang Haoquan, Han Yan, Zeng Guangyu. 2002. The research on measuring the ultrasonic attenuation coefficient about nonmetal composite materials. Journal of Test and Measurement Technology (in Chinese), 16(4): 249–251

|

| [40] |

Wang Qingkai, Li Zhijun, Lei Ruibo, et al. 2018. Estimation of the uniaxial compressive strength of Arctic sea ice during melt season. Cold Regions Science and Technology, 151: 9–18. doi: 10.1016/j.coldregions.2018.03.002

|

| [41] |

Wang Sijing, Tang Darong, Yang Zhifa, et al. 1974. Preliminary applications of acoustic technique for engineering rock measurements. Chinese Journal of Geology (in Chinese), 9(3): 269–282

|

| [42] |

Weeks W F, Ackley S F. 1986. The growth, structure, and properties of sea ice. In: The Geophysics of Sea Ice. Boston, MA, USA: Springer, 9–164

|

| [43] |

Yu Tianlai, Yuan Zhengguo, Huang Meilan. 2009. Experimental study on mechanical behavior of river ice. Journal of Liaoning Technical University (Natural Science Edition) (in Chinese), 28(6): 937–940

|

| [44] |

Zuo Guangyu, Dou Yinke, Chang Xiaomin, et al. 2018a. Design and performance analysis of a Multilayer Sea Ice temperature sensor used in polar region. Sensors, 18(12): 4467. doi: 10.3390/s18124467

|

| [45] |

Zuo Guangyu, Dou Yinke, Lei Ruibo. 2018b. Discrimination algorithm and procedure of snow depth and sea ice thickness determination using measurements of the vertical ice temperature profile by the ice-tethered buoys. Sensors, 18(12): 4162. doi: 10.3390/s18124162

|

| 1. | Jiahui Gao, Yuxiang Zhang, Dingyi Ma, et al. In-situ characterization of wave velocity in ice cover with seismic observation on guided wave. Cold Regions Science and Technology, 2025, 231: 104392. doi:10.1016/j.coldregions.2024.104392 | |

| 2. | Yabo Zhang, Junfeng Ge, Kang Gui, et al. Mixed-phase measurement during atmospheric icing using ultrasonic pulse-echo (UPE) and signal separation techniques. Measurement, 2025, 245: 116679. doi:10.1016/j.measurement.2025.116679 | |

| 3. | Menno Demmenie, Paul Kolpakov, Boaz van Casteren, et al. Damage due to ice crystallization. Scientific Reports, 2025, 15(1) doi:10.1038/s41598-025-86117-5 | |

| 4. | Yingbo Jiang, Tingchang Yin, Guanlong Guo, et al. Property evaluation by numerical modelling based on voxelized images – Accuracy versus resolution. Computers and Geotechnics, 2024, 165: 105887. doi:10.1016/j.compgeo.2023.105887 | |

| 5. | Suzi Liang, Bradley E. Treeby, Eleanor Martin. Review of the Low-Temperature Acoustic Properties of Water, Aqueous Solutions, Lipids, and Soft Biological Tissues. IEEE Transactions on Ultrasonics, Ferroelectrics, and Frequency Control, 2024, 71(5): 607. doi:10.1109/TUFFC.2024.3381451 | |

| 6. | Sujay Deshpande, Ane Sæterdal, Per-Arne Sundsbø. Experiments With Sea Spray Icing: Investigation of Icing Rates. Journal of Offshore Mechanics and Arctic Engineering, 2024, 146(1) doi:10.1115/1.4062255 | |

| 7. | Yan Zhang, Xiaozhuang Wang, Tongguo Zhao, et al. Promotional effects of ultrasound and oscillation on sea ice desalination. Separation and Purification Technology, 2024, 347: 127622. doi:10.1016/j.seppur.2024.127622 | |

| 8. | Mengyao Ai, Ge Gao, Zhiwei Zhao, et al. Experimental study on fracture failure characteristics evaluation of wooden pallets in humid-cold environment based on piezoelectric technology. Industrial Crops and Products, 2024, 222: 119627. doi:10.1016/j.indcrop.2024.119627 | |

| 9. | Xingchang Zeng, Huiling Ong, Luke Haworth, et al. Fundamentals of Monitoring Condensation and Frost/Ice Formation in Cold Environments Using Thin-Film Surface-Acoustic-Wave Technology. ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces, 2023, 15(29): 35648. doi:10.1021/acsami.3c04854 | |

| 10. | Xiaomin Chang, Ming Xue, Pandeng Li, et al. Experimental Research on Ice Density Measurement Method Based on Ultrasonic Waves. Water, 2023, 15(23): 4065. doi:10.3390/w15234065 |