| Citation: | Yangjun Chen, Jinxu Chen, Yi Wang, You Jiang, Minfang Zheng, Yusheng Qiu, Min Chen. Sources and transformations of nitrite in the Amundsen Sea in summer 2019 and 2020 as revealed by nitrogen and oxygen isotopes[J]. Acta Oceanologica Sinica, 2023, 42(4): 16-24. doi: 10.1007/s13131-022-2111-4 |

Nitrogen (N) is an essential nutrient needed for marine organisms to grow. Nitrate (

The Southern Ocean plays a pivotal role in oceanic nutrient cycling and climate change. For example, global cooling during the Late Pleistocene Ice Age was thought to have resulted from enhanced carbon storage in the Southern Ocean, thereby reducing atmospheric carbon dioxide (Chalk et al., 2017; Jaccard et al., 2013; Martínez-Garcia et al., 2011). One of the typical features in the Southern Ocean is that major nutrients such as

Current research on the N cycle in the Southern Ocean has focused more on

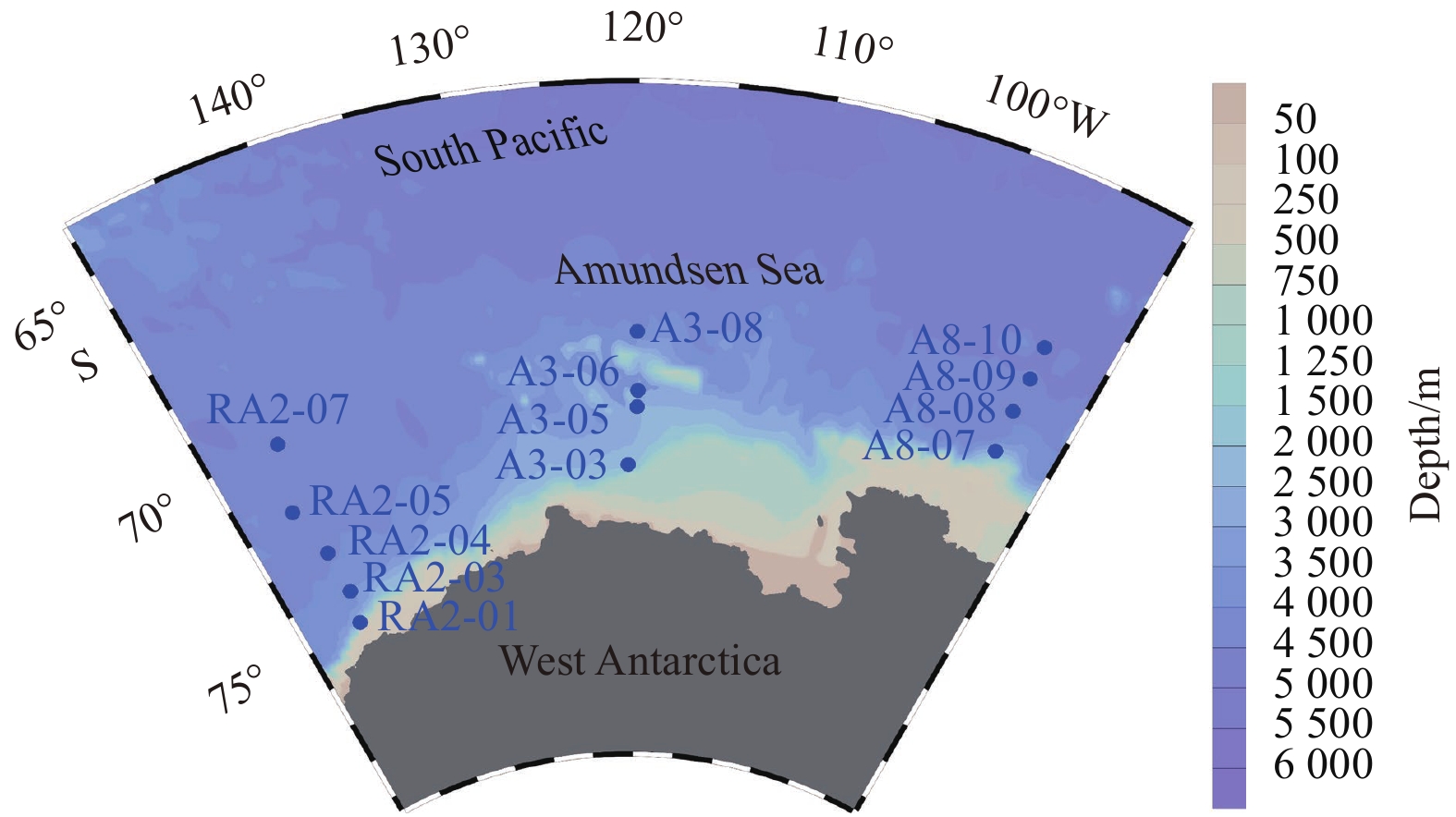

Seawater samples were collected through China’s 35th and 36th Antarctic Research Expeditions (CHINARE). During the 35th CHINARE conducted by R/V Xuelong, samples were collected from four sites at the Section A8 from January 16 to 19, 2019. During the 36th CHINARE conducted by R/V Xuelong, samples were collected from nine sites at the Sections A3 and RA2 from January 12 to February 5, 2020. Sections RA2, A3 and A8 are located in the western, central and eastern parts of the Amundsen Sea, respectively (Fig.1). Samples were collected from a 12 L Niskin bottle mounted on a Conductivity-Temperature-Depth (CTD) rosette. Only water samples above 150 m were collected for N and O isotopes analysis because the

Temperature and salinity were measured in situ by CTD probes on board (SBE 911plus, Sea Bird). The measurement accuracy of temperature and conductivity is 0.001℃ and 0.0003 S/m, respectively. Chl a concentration was measured and calibrated directly from the probe equipped on the CTD.

The concentrations of

An optimized azide reduction method was used to simultaneously measure the N and O isotopic compositions in

The sea surface temperature (SST) in the Amundsen Sea ranged from −1.56℃ to 0.38℃, with the largest variation in the Section A8 in the east (Fig. 2a). The temperature minimum (Tmin) and temperature maximum (Tmax) appeared at different depths in sequence, with Tmin at 50−200 m depth and Tmax at 300−500 m depth (except RA2-03 at 1000 m). Below Tmax, the temperature gradually decreased and gradually became stable (Fig. 2d, gray line). Tmin and Tmax are ubiquitous features in the Southern Ocean (Altabet and Francois, 2001; Bindoff et al., 2000; DiFiore et al., 2009, 2010; Kemeny et al., 2016; Fripiat et al., 2019; Smart et al., 2015). The Tmin reflects the characteristics of winter residual water retained in summer (Altabet and Francois, 2001; DiFiore et al., 2010), and the Tmax reflects the influence of Circumpolar Deep Water (Bindoff et al., 2000; DiFiore et al., 2009; Fripiat et al., 2019).

The sea surface salinity in the Amundsen Sea varied between 32.68 and 33.97. Unlike the distribution of SST, the surface salinity in the three regions was relatively uniform. The salinity gradually increased with the increase of depth and stabilized below 500 m (Fig. 2e).

The

The distribution of

In the Section RA2 in the western Amundsen Sea, due to the limitation of

δ18

In the Section A3 of the central Amundsen Sea, the δ15

The highest value of δ18

The variation ranges of δ15

In this study, the δ15

The theoretical range of δ15

Combining the influences of the above conventional N cycle processes, the potential variation range of δ15

As one of the sources of

Estimating the potential range of δ18

Combining the influences of the above conventional N cycle processes, the potential variation range of δ18

According to the above isotopic fractionation of the traditional N cycle processes, in the upper water of the Southern Ocean, the variation range of δ15

The existence of PNM has been observed in the three sections of the Amundsen Sea (Fig. 2c). Here, we analyze the source of

The formation of PNM requires that the source of

Our results show that the vast majority of δ15

The N and O isotopic compositions of

Measurements of N and O isotopic compositions of

|

Altabet M A, Francois R. 2001. Nitrogen isotope biogeochemistry of the Antarctic Polar Frontal Zone at 170°W. Deep-Sea Research Part II: Topical Studies in Oceanography, 48(19–20): 4247–4273

|

|

Bett D T, Holland P R, Garabato A C N, et al. 2020. The impact of the Amundsen Sea freshwater balance on ocean melting of the west Antarctic ice sheet. Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans, 125(9): e2020JC016305

|

|

Bindoff N L, Rosenberg M A, Warner M J. 2000. On the circulation and water masses over the Antarctic continental slope and rise between 80 and 150°E. Deep-Sea Research Part II: Topical Studies in Oceanography, 47(12–13): 2299–2326

|

|

Bourbonnais A, Altabet M A, Charoenpong C N, et al. 2015. N-loss isotope effects in the Peru oxygen minimum zone studied using a mesoscale eddy as a natural tracer experiment. Global Biogeochemical Cycles, 29(6): 793–811. doi: 10.1002/2014GB005001

|

|

Brandhorst W. 1959. Nitrification and denitrification in the eastern tropical North Pacific. ICES Journal of Marine Science, 25(1): 3–20. doi: 10.1093/icesjms/25.1.3

|

|

Buchwald C, Casciotti K L. 2010. Oxygen isotopic fractionation and exchange during bacterial nitrite oxidation. Limnology and Oceanography, 55(3): 1064–1074. doi: 10.4319/lo.2010.55.3.1064

|

|

Buchwald C, Casciotti K L. 2013. Isotopic ratios of nitrite as tracers of the sources and age of oceanic nitrite. Nature Geoscience, 6(4): 308–313. doi: 10.1038/ngeo1745

|

|

Buchwald C, Santoro A E, McIlvin M R, et al. 2012. Oxygen isotopic composition of nitrate and nitrite produced by nitrifying cocultures and natural marine assemblages. Limnology and Oceanography, 57(5): 1361–1375. doi: 10.4319/lo.2012.57.5.1361

|

|

Buchwald C, Santoro A E, Stanley R H R, et al. 2015. Nitrogen cycling in the secondary nitrite maximum of the eastern tropical North Pacific off Costa Rica. Global Biogeochemical Cycles, 29(12): 2061–2081. doi: 10.1002/2015GB005187

|

|

Casciotti K L. 2009. Inverse kinetic isotope fractionation during bacterial nitrite oxidation. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta, 73(7): 2061–2076. doi: 10.1016/j.gca.2008.12.022

|

|

Casciotti K L. 2016a. Nitrite isotopes as tracers of marine N cycle processes. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A Mathematical, Physical and Engineering Sciences, 374(2081): 20150295

|

|

Casciotti K L. 2016b. Nitrogen and oxygen isotopic studies of the marine nitrogen cycle. Annual Review of Marine Science, 8: 379–407. doi: 10.1146/annurev-marine-010213-135052

|

|

Casciotti K L, Böhlke J K, McIlvin M R, et al. 2007. Oxygen isotopes in nitrite: analysis, calibration, and equilibration. Analytical Chemistry, 79(6): 2427–2436. doi: 10.1021/ac061598h

|

|

Casciotti K L, Buchwald C, McIlvin M. 2013. Implications of nitrate and nitrite isotopic measurements for the mechanisms of nitrogen cycling in the Peru oxygen deficient zone. Deep-Sea Research Part I: Oceanographic Research Papers, 80: 78–93. doi: 10.1016/j.dsr.2013.05.017

|

|

Casciotti K L, McIlvin M, Buchwald C. 2010. Oxygen isotopic exchange and fractionation during bacterial ammonia oxidation. Limnology and Oceanography, 55(2): 753–762. doi: 10.4319/lo.2010.55.2.0753

|

|

Casciotti K L, Sigman D M, Hastings M G, et al. 2002. Measurement of the oxygen isotopic composition of nitrate in seawater and freshwater using the denitrifier method. Analytical Chemistry, 74(19): 4905–4912. doi: 10.1021/ac020113w

|

|

Casciotti K L, Sigman D M, Ward B B. 2003. Linking diversity and stable isotope fractionation in ammonia-oxidizing bacteria. Geomicrobiology Journal, 20(4): 335–353. doi: 10.1080/01490450303895

|

|

Chalk T B, Hain M P, Foster G L, et al. 2017. Causes of ice age intensification across the mid-pleistocene transition. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 114(50): 13114–13119. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1702143114

|

|

Checkley Jr D M, Miller C A. 1989. Nitrogen isotope fractionation by oceanic zooplankton. Deep-Sea Research Part A: Oceanographic Research Papers, 36(10): 1449–1456

|

|

Chen Yangjun, Bardhan P, Zhao Xiufeng, et al. 2021. Nitrite cycle indicated by dual isotopes in the northern South China Sea. Journal of Geophysical Research: Biogeosciences, 126(7): e2020JG006129

|

|

Chen Yangjun, Chen Min. 2022. Nitrite cycling in warming Arctic and subarctic waters. Geophysical Research Letters, 49(12): e2021-GL096947

|

|

Chen Yangjun, Chen Min, Chen Jinxu, et al. 2022. Dual isotopes of nitrite in the Amundsen Sea in summer. Science of the Total Environment, 843: 157055. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2022.157055

|

|

Codispoti L A, Friederich G E, Packard T T, et al. 1986. High nitrite levels off northern Peru: a signal of instability in the marine denitrification rate. Science, 233(4769): 1200–1202. doi: 10.1126/science.233.4769.1200

|

|

DiFiore P J, Sigman D M, Dunbar R B. 2009. Upper ocean nitrogen fluxes in the Polar Antarctic Zone: constraints from the nitrogen and oxygen isotopes of nitrate. Geochemistry, Geophysics, Geosystems, 10(11): Q11016

|

|

DiFiore P J, Sigman D M, Karsh K L, et al. 2010. Poleward decrease in the isotope effect of nitrate assimilation across the Southern Ocean. Geophysical Research Letters, 37(17): L17601

|

|

DiFiore P J, Sigman D M, Trull T W, et al. 2006. Nitrogen isotope constraints on subantarctic biogeochemistry. Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans, 111(C8): C08016

|

|

Dore J E, Karl D M. 1996. Nitrification in the euphotic zone as a source for nitrite, nitrate, and nitrous oxide at station ALOHA. Limnology and Oceanography, 41(8): 1619–1628. doi: 10.4319/lo.1996.41.8.1619

|

|

Fripiat F, Elskens M, Trull T W, et al. 2015a. Significant mixed layer nitrification in a natural iron-fertilized bloom of the Southern Ocean. Global Biogeochemical Cycles, 29(11): 1929–1943. doi: 10.1002/2014GB005051

|

|

Fripiat F, Martínez-García A, Fawcett S E, et al. 2019. The isotope effect of nitrate assimilation in the Antarctic Zone: Improved estimates and paleoceanographic implications. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta, 247: 261–279. doi: 10.1016/j.gca.2018.12.003

|

|

Fripiat F, Sigman D M, Fawcett S E, et al. 2014. New insights into sea ice nitrogen biogeochemical dynamics from the nitrogen isotopes. Global Biogeochemical Cycles, 28(2): 115–130. doi: 10.1002/2013GB004729

|

|

Fripiat F, Sigman D M, Massé G, et al. 2015b. High turnover rates indicated by changes in the fixed N forms and their stable isotopes in Antarctic landfast sea ice. Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans, 120(4): 3079–3097. doi: 10.1002/2014JC010583

|

|

Froneman P W, Laubscher R K, Mcquaid C D. 2001. Size-fractionated primary production in the South Atlantic and Atlantic sectors of the Southern Ocean. Journal of Plankton Research, 23(6): 611–622. doi: 10.1093/plankt/23.6.611

|

|

Granger J, Boshers D S, Böhlke J K, et al. 2020. The influence of sample matrix on the accuracy of nitrite N and O isotope ratio analyses with the azide method. Rapid Communications in Mass Spectrometry, 34(1): e8569

|

|

Granger J, Sigman D M, Needoba J A, et al. 2004. Coupled nitrogen and oxygen isotope fractionation of nitrate during assimilation by cultures of marine phytoplankton. Limnology and Oceanography, 49(5): 1763–1773. doi: 10.4319/lo.2004.49.5.1763

|

|

Hoch M P, Fogel M L, Kirchman D L. 1992. Isotope fractionation associated with ammonium uptake by a marine bacterium. Limnology and Oceanography, 37(7): 1447–1459. doi: 10.4319/lo.1992.37.7.1447

|

|

Hu H, Bourbonnais A, Larkum J, et al. 2016. Nitrogen cycling in shallow low-oxygen coastal waters off Peru from nitrite and nitrate nitrogen and oxygen isotopes. Biogeosciences, 13(5): 1453–1468. doi: 10.5194/bg-13-1453-2016

|

|

Hutchins D A, Capone D G. 2022. The marine nitrogen cycle: new developments and global change. Nature Reviews Microbiology, 20(7): 401–414. doi: 10.1038/s41579-022-00687-z

|

|

Jaccard S L, Hayes C T, Martínez-García A, et al. 2013. Two modes of change in Southern Ocean productivity over the past million years. Science, 339(6126): 1419–1423. doi: 10.1126/science.1227545

|

|

Jochem F J, Mathot S, Quéguiner B. 1995. Size-fractionated primary production in the open Southern Ocean in austral spring. Polar Biology, 15(6): 381–392

|

|

Karsh K L, Granger J, Kritee K, et al. 2012. Eukaryotic assimilatory nitrate reductase fractionates N and O isotopes with a ratio near unity. Environmental Science & Technology, 46(11): 5727–5735

|

|

Kemeny P C, Weigand M A, Zhang R, et al. 2016. Enzyme-level interconversion of nitrate and nitrite in the fall mixed layer of the Antarctic Ocean. Global Biogeochemical Cycles, 30(7): 1069–1085. doi: 10.1002/2015GB005350

|

|

Kiefer D A, Olson R J, Holm-Hansen O. 1976. Another look at the nitrite and chlorophyll maxima in the central North Pacific. Deep-Sea Research and Oceanographic Abstracts, 23(12): 1199–1208. doi: 10.1016/0011-7471(76)90895-0

|

|

Kobayashi K, Fukushima K, Onishi Y, et al. 2021. Influence of δ18O of water on measurements of δ18O of nitrite and nitrate. Rapid Communications in Mass Spectrometry, 35(2): e8979

|

|

Kowalchuk G A, Stephen J R. 2001. Ammonia-oxidizing bacteria: a model for molecular microbial ecology. Annual Review of Microbiology, 55: 485–529. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.55.1.485

|

|

Lehmann M F, Bernasconi S M, Barbieri A, et al. 2002. Preservation of organic matter and alteration of its carbon and nitrogen isotope composition during simulated and in situ early sedimentary diagenesis. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta, 66(20): 3573–3584. doi: 10.1016/S0016-7037(02)00968-7

|

|

Liu Sumei, Ning Xiaoyan, Dong Shuhang, et al. 2020. Source versus recycling influences on the isotopic composition of nitrate and nitrite in the East China Sea. Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans, 125(8): e2020JC016061

|

|

Lomas M W, Lipschultz F. 2006. Forming the primary nitrite maximum: nitrifiers or phytoplankton?. Limnology and Oceanography, 51(5): 2453–2467. doi: 10.4319/lo.2006.51.5.2453

|

|

Lourey M J, Trull T W, Sigman D M. 2003. Sensitivity of δ15N of nitrate, surface suspended and deep sinking particulate nitrogen to seasonal nitrate depletion in the Southern Ocean. Global Biogeochemical Cycles, 17(3): 1081

|

|

Mackey K R M, Bristow L, Parks D R, et al. 2011. The influence of light on nitrogen cycling and the primary nitrite maximum in a seasonally stratified sea. Progress in Oceanography, 91(4): 545–560. doi: 10.1016/j.pocean.2011.09.001

|

|

Macko S A, Estep M L F, Engel M H, et al. 1986. Kinetic fractionation of stable nitrogen isotopes during amino acid transamination. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta, 50(10): 2143–2146. doi: 10.1016/0016-7037(86)90068-2

|

|

Martin J H, Gordon R M, Fitzwater S E. 1990. Iron in Antarctic waters. Nature, 345(6271): 156–158. doi: 10.1038/345156a0

|

|

Martínez-Garcia A, Rosell-Melé A, Jaccard S L, et al. 2011. Southern Ocean dust-climate coupling over the past four million years. Nature, 476(7360): 312–315. doi: 10.1038/nature10310

|

|

McIlvin M R, Altabet M A. 2005. Chemical conversion of nitrate and nitrite to nitrous oxide for nitrogen and oxygen isotopic analysis in freshwater and seawater. Analytical Chemistry, 77(17): 5589–5595. doi: 10.1021/ac050528s

|

|

Mdutyana M, Thomalla S J, Philibert R, et al. 2020. The seasonal cycle of nitrogen uptake and nitrification in the Atlantic sector of the Southern Ocean. Global Biogeochemical Cycles, 34(7): e2019GB006363

|

|

Mitchell B G, Brody E A, Holm-Hansen O, et al. 1991. Light limitation of phytoplankton biomass and macronutrient utilization in the Southern Ocean. Limnology and Oceanography, 36(8): 1662–1677. doi: 10.4319/lo.1991.36.8.1662

|

|

Moore C M, Mills M M, Arrigo K R, et al. 2013. Processes and patterns of oceanic nutrient limitation. Nature Geoscience, 6(9): 701–710. doi: 10.1038/ngeo1765

|

|

Naughten K A, Holland P R, Dutrieux P, et al. 2022. Simulated twentieth-century ocean warming in the Amundsen Sea, west Antarctica. Geophysical Research Letters, 49(5): e2021GL094566

|

|

Newell S E, Babbin A R, Jayakumar A, et al. 2011. Ammonia oxidation rates and nitrification in the Arabian Sea. Global Biogeochemical Cycles, 25(4): GB4016

|

|

Newell S E, Fawcett S E, Ward B B. 2013. Depth distribution of ammonia oxidation rates and ammonia-oxidizer community composition in the Sargasso Sea. Limnology and Oceanography, 58(4): 1491–1500. doi: 10.4319/lo.2013.58.4.1491

|

|

Olson R J. 1981. 15N tracer studies of the primary nitrite maximum. Journal of Marine Research, 39(2): 203–226

|

|

Peng Xuefeng, Fawcett S E, Van Oostende N, et al. 2018. Nitrogen uptake and nitrification in the subarctic North Atlantic Ocean. Limnology and Oceanography, 63(4): 1462–1487. doi: 10.1002/lno.10784

|

|

Peng Xuefeng, Fuchsman C A, Jayakumar A, et al. 2015. Ammonia and nitrite oxidation in the Eastern Tropical North Pacific. Global Biogeochemical Cycles, 29(12): 2034–2049. doi: 10.1002/2015GB005278

|

|

Santoro A E, Sakamoto C M, Smith J M, et al. 2013. Measurements of nitrite production in and around the primary nitrite maximum in the central California Current. Biogeosciences, 10(11): 7395–7410. doi: 10.5194/bg-10-7395-2013

|

|

Shepherd A, Ivins E, Rignot E, et al. 2018. Mass balance of the Antarctic Ice Sheet from 1992 to 2017. Nature, 558(7709): 219–222. doi: 10.1038/s41586-018-0179-y

|

|

Sigman D M, Altabet M A, McCorkle D C, et al. 1999. The δ15N of nitrate in the Southern Ocean: consumption of nitrate in surface waters. Global Biogeochemical Cycles, 13(4): 1149–1166. doi: 10.1029/1999GB900038

|

|

Smart S M, Fawcett S E, Thomalla S J, et al. 2015. Isotopic evidence for nitrification in the Antarctic winter mixed layer. Global Biogeochemical Cycles, 29(4): 427–445. doi: 10.1002/2014GB005013

|

|

Smith J M, Chavez F P, Francis C A. 2014. Ammonium uptake by phytoplankton regulates nitrification in the sunlit ocean. PLoS ONE, 9(9): e108173. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0108173

|

|

Vo J, Inwood W, Hayes J M, et al. 2013. Mechanism for nitrogen isotope fractionation during ammonium assimilation by Escherichia coli K12. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 110(21): 8696–8701. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1216683110

|

|

Ward B B. 2008. Nitrification in marine systems. In: Capone D G, Bronk D A, Mulholland M R, et al., eds. Nitrogen in the Marine Environment. 2nd ed. San Diego: Academic Press, 199–261

|

|

Ward B B, Talbot M C, Perry M J. 1984. Contributions of phytoplankton and nitrifying bacteria to ammonium and nitrite dynamics in coastal waters. Continental Shelf Research, 3(4): 383–398. doi: 10.1016/0278-4343(84)90018-9

|

|

Waser N A D, Harrison P J, Nielsen B, et al. 1998. Nitrogen isotope fractionation during the uptake and assimilation of nitrate, nitrite, ammonium, and urea by a marine diatom. Limnology and Oceanography, 43(2): 215–224. doi: 10.4319/lo.1998.43.2.0215

|