| Citation: | Jianbo Cui, Yunhua Wang, Yanmin Zhang, Huimin Li, Wenzheng Jiang, Yushi Zhang, Xin Li. A new model for Doppler shift of C-band echoes backscattered from sea surface[J]. Acta Oceanologica Sinica, 2023, 42(6): 100-111. doi: 10.1007/s13131-022-2144-8 |

As the scattering elements on sea surface are moving under the actions of wind, waves and current, the frequency of a radar signal backscattered from oceanic surface thus experiences a Doppler shift, which is proportional to the line-of-sight velocity of the scattering facets and weighted by their backscattered power (Keller et al., 1986). Consequently, the Doppler features could provide information on the ocean dynamic conditions, in complement to the normalized radar cross section (NRCS) which is related to the surface roughness. Thus, the studies on Doppler features are of practical importance in a number of research areas such as sea surface wind retrieving, sea waves monitoring and oceanic surface current measuring (Chapron et al., 2005; Johannessen et al., 2005; Kudryavtsev et al., 2005; Karaev et al., 2008; Johnson et al., 2009). In recent years, the properties of Doppler spectrum from sea surface have been the subject of extensive investigations, both theoretically and experimentally (Crombie, 1955; Bass et al., 1968; Wright and Keller, 1971; Barrick, 1977; Lipa, 1978; Mouche et al., 2008).

On the theoretical side, Crombie (1955) first investigated the properties of Doppler spectrum based on Bragg theory in the early stage. In Barrick (1977), Barrick built a perturbative model based on a representation of sea waves up to second order, which has been widely used for HF and VHF radars. For microwaves, besides the Bragg theory, the Kirchhoff approximation (KA) and the small slope approximation (SSA) can also be used to predict the Doppler shift of the signals from sea surface (Mouche et al., 2008). However, it should be pointed out that the Doppler shift predicted by the Kirchhoff approximation method (KA), the Bragg theory, and the first-order small slope approximation (SSA-1) in co-polarized configuration are insensitive to the polarization state. And experiment results show that the Doppler shift of horizontally polarized signals are generally larger than those vertically polarized case. Bass et al. (1968) and Wright and Keller (1971) established a two-scale surface scattering model (TSM) which includes modulation by the large scale waves, and makes the results closer to the real sea surface situation. What’s more, the polarization dependence of the Doppler shift can also be well explained by using the two scale surface scattering model. In Wang and Zhang (2011) and Wang et al. (2012, 2013), the differences between co-polarized have been explained by the TSM, and the effects of tilt and hydrodynamic modulation have also been analyzed, which gives a quantitative interpretation of Doppler shift of sea surface echo. Up to now, the two-scale surface model is still as the most practical model to theoretically describe the Doppler spectrum of microwave scattering from sea surface (Zavorotny and Voronovich, 1998; Fuks and Voronovich, 2002). In several researches (Zavorotny and Voronovich, 1998; Fuks and Voronovich, 2002; Wang and Zhang, 2011 ; Wang et al., 2012, 2013), however, it should be pointed out that the local NRCS is calculated by the Bragg scattering theory. As we all know, the scattering coefficient calculated by the Bragg scattering theory generally has an obvious discrepancy with the actual signal backscattered from sea surface in real condition. Compared with the Bragg scattering theory, for a specific radar frequency band, the empirical geophysical model function (GMF) can be used to estimate the NRCS backscattered from sea surface more accurately (Verspeek et al., 2012; Li and Lehner, 2014; Mouche and Chapron, 2015; Shao et al., 2016).

In recent years, the numerical methods were also employed to investigate the Doppler spectra of backscattering from one-dimensional sea surfaces (Toporkov and Brown, 2000; Johnson et al., 2001; Hayslip et al., 2003). At low grazing angles (LGA), Toporkov et al. found that the results of numerical simulations showed an obvious broadening of the bandwidth for nonlinear surfaces and a separation of the vertical and horizontal polarization spectra (Toporkov and Brown, 2000). But for the linear sea surface, this spectral separation cannot be observed. Further, the influences of the hydrodynamic models on the Doppler spectra of L-band backscattered fields have been discussed by Johnson and Hayslip et al. (Johnson et al., 2001; Hayslip et al., 2003). In spite of the advantages of the numerical methods, several questions should be mentioned as following: on the one hand, in order to obtain exact numerical results, Doppler simulations turn out to be quite computationally expensive; on the other hand, the influences of different factors, such as hydrodynamic modulation, tilt modulation of large scale waves and so on cannot be assessed individually.

In addition to the theoretical and the numerical methods, a serious of the empirical Geophysical Model Functions (GMF) based on the Doppler shift observations combined with wind and sea state information have been developed in recent studies. For instance, a C-band empirical geophysical model function (CDOP) has been built for estimating wave-induced Doppler shift (Mouche et al., 2012). On the basis of the observed Doppler shift by Sentine-l SAR, another empirical geophysical model, called CDOP-3S which combined wave information into the model, was established by Moiseev et al. (2020). However, the CDOP-3S model performs an overfit of the empirical GMF during training. A new GMF called CDOP-3SiX has been trained based on the coastal data set in Moiseev et al. (2022). Due to addition of the sea wind and swell information, the CDOP-3SiX improves the accuracy of sea state contribution estimates compared to CDOP model. Although the development of the empirical geophysical model function can significantly facilitate the application of the Doppler information in ocean remote sensing. However, the accurate of the empirical geophysical model depends on the sensor’s performance and optimal instrumental configurations. In addition, the empirical models are not easily used to analyze the physical mechanisms that affect the Doppler properties.

To progress in such investigations, our purpose in this paper is to numerically evaluate the wind induced Doppler shift of the echoes backscattered from sea surface by combining the TSM model and nonlinear sea wave model. Predictions will help to better understand the influence mechanism of incidence angle, polarization sensitivities, and modulation effects of large scale waves. What’s more, in this study, the scattering coefficient in the TSM is calculated by the empirical CSAR model (Mouche and Chapron, 2015) rather than Bragg model to get more accurate results. Numerical results show that the Doppler shift of the C-band sea echoes at moderate incidence angles can be well predicted by the method in this work. In order to facilitate the application, a semi-empirical CSAR-DOP model is also developed based on the predicted Doppler shift in this work. In the following section, the numerical theory for Doppler shift is presented in Section II. The results of the numerical models are analyzed in Section III. Using the predicted Doppler shift, a polynomial fitting formula (CSAR-DOP model) is developed in Section IV. The concluding remarks and perspectives are provided in Section V.

As the most practical model for theoretical description of microwave Doppler spectrum from sea surface, the two- scale model can be used to give a qualitative and quantitative interpretation of the Doppler shift. In TSM model, sea surface is artificially partitioned into small- and large-scale waves, such that

| $$ Z\left( {x,y,t} \right) = {Z_l}\left( {x,y,t} \right){\text{ + }}{Z_s}\left( {x,y,t} \right), $$ | (1) |

where

| $$ W\left( {\boldsymbol{K}} \right) = {W_{ms}}\left( {\boldsymbol{K}} \right) + {W_l}\left( {\boldsymbol{K}} \right), $$ | (2) |

where

According to the linear theory, the sea surface can be described as a sum of large number of harmonics with different amplitudes, frequencies, and random phases. However, if we aim at studying radar Doppler character, the nonlinearities of actual sea surface cannot be neglected, especially, the skewness properties would induce obvious effect on the Doppler shift. In general, the nonlinear sea surface can be expanded in perturbation series. The first order perturbation term corresponds to the linear surface and the higher order corrections come from the expansion of the hydrodynamic formulas in terms of wave interactions. For large-scale waves, the narrow-band assumption is acceptable. On the basis of this narrow band assumption, Tayfun (1986) proposed a nonlinear sea surface model, which results in a random sea surface whose crests are narrow and peaked, and whose troughs are long and flat. Such asymmetry of the vertical direction is referred to as vertical-skewness. At the same time, the horizontal-skewness, which directly affects the surface slope distribution, also occurs in sea waves. In Fung (1994), Fung found that, compared to vertical-skewness, the horizontal-skewness induces more remarkable influence on backscattered signal. The Lagrange Model with linked components (hereinafter referred to as LMLC) is an optional hydrodynamic model for the nonlinear water waves (Lindgren, 2009; Lindgren and Åberg, 2009). The LMLC model can produce the realistic vertical- and horizontal-skewness. For two-dimensional deep water waves, the LMLC can be written as

| $$ \begin{split}{Z_l}\left( {x,y,t} \right) =& \sum\limits_{m = - M/2}^{M/2 - 1} \;\sum\limits_{n = - N/2}^{N/2 - 1} F\left( {{K_{xm}},{K_{yn}}} \right)\times \\ &\exp\left[ {{\rm{i}}\left( {{K_{xm}}{x_{\text{0}}} + {K_{yn}}{y_{\text{0}}}} \right) - {\rm{i}}{\omega _{mn}}t} \right], \end{split}$$ | (3) |

with

| $$ \begin{split} x =& {x_{\text{0}}} - \sum\limits_{m = - M/2}^{M/2 - 1} \;\sum\limits_{n = - N/2}^{N/2 - 1} {\rm{i}}\frac{{{K_{xm}}}}{{{K_{mn}}}}F({K_{xm}},{K_{yn}})\exp [{\rm{i}}({K_{xm}}{x_{\text{0}}} +\\ & {K_{yn}}{y_{\text{0}}}) - {\rm{i}}{\omega _{mn}}t] + \sum\limits_{m = - M/2}^{M/2 - 1}\; \sum\limits_{n = - N/2}^{N/2 - 1} {\alpha _{mn}}\frac{{{K_{xm}}}}{{{K_{mn}}}}F({K_{xm}},{K_{yn}}) \times\\ &\exp [{\rm{i}}({K_{xm}}{x_{\text{0}}} + {K_{yn}}{y_{\text{0}}}) - {\rm{i}}{\omega _{mn}}t], \end{split} $$ | (4) |

| $$ \begin{split} y =& {y_{\text{0}}} - \sum\limits_{m = - M/2}^{M/2 - 1}\; \sum\limits_{n = - N/2}^{N/2 - 1} {{\rm{i}}\frac{{{K_{yn}}}}{{{K_{mn}}}}F({K_{xm}},{K_{yn}})\exp [{\rm{i}}({K_{xm}}{x_{\text{0}}}} +\\ &{K_{yn}}{y_{\text{0}}}) - {\rm{i}}{\omega _{mn}}t] + \sum\limits_{m = - M/2}^{M/2 - 1} \; \sum\limits_{n = - N/2}^{N/2 - 1} {\alpha _{mn}}\frac{{{K_{yn}}}}{{{K_{mn}}}}F({K_{xm}},{K_{yn}})\times\\ &\exp [{\rm{i}}({K_{xm}}{x_{\text{0}}} + {K_{yn}}{y_{\text{0}}}) - {\rm{i}}{\omega _{mn}}t] , \end{split} $$ | (5) |

where

| $$ {V_z} = - \sum\limits_{m = - M/2}^{M/2 - 1} {\;\sum\limits_{n = - N/2}^{N/2 - 1} {{\rm{i}}{\omega _{mn}}F({K_{xm}},{K_{yn}})\exp [{\rm{i}}({K_{xm}}x} + {K_{yn}}y) - {\rm{i}}{\omega _{mn}}t]} , $$ | (6) |

| $$ {V_x} = \sum\limits_{m = - M/2}^{M/2 - 1} {\;\sum\limits_{n = - N/2}^{N/2 - 1} {{\omega _{mn}}\frac{{{K_{xm}}}}{K}F({K_{xm}},{K_{yn}})\exp [{\rm{i}}({K_{xm}}x} + {K_{yn}}y) - {\rm{i}}{\omega _{mn}}t]} , $$ | (7) |

| $$ {V_y} = \sum\limits_{m = - M/2}^{M/2 - 1} {\;\sum\limits_{n = - N/2}^{N/2 - 1} {{\omega _{mn}}\frac{{{K_{yn}}}}{K}F({K_{xm}},{K_{yn}})\exp [{\rm{i}}({K_{xm}}x} + {K_{yn}}y) - {\rm{i}}{\omega _{mn}}t]} . $$ | (8) |

The small-scale roughness of sea waves would be modulated by the large-scale underlying waves, and the spatial variation of

| $$ \begin{split}{W_{ms}}({\boldsymbol{K}} ) =& {W_s}({\boldsymbol{K}} )\left\{ 1 + \sum\limits_{m = - M/2 + 1}^{M/2} {\sum\limits_{n = - N/2 + 1}^{N/2} {{M_{{\rm{hydr}}}}F({K_{xm}},{K_{yn}})} }\times\right.\\ &\exp [{\rm{i}}({K_{{\text{x}}m}}x + {K_{yn}}y) - {\rm{i}}{\omega _{mn}}t] \Biggr\},\\[-20pt]\end{split}$$ | (9) |

where

| $$ {M_{{\text{hydr}}}} = 4.5\left| {{{\boldsymbol{K}} _l}} \right|\omega \frac{{\omega - {\rm{i}}\mu }}{{{\omega ^2} + {\mu ^2}}}{{{\cos}} ^2}\left( {{{\boldsymbol{K}} _l},{{\boldsymbol{K}} _s}} \right) , $$ | (10) |

where

| $$\begin{split} {\sigma _{{\text{pp}}}}({\theta '_i}) \approx &\overline {{\sigma _{{\text{pp}}}}({\theta '_i})} \Biggr\{ 1 + \sum\limits_{m = - M/2 + 1}^{M/2}\; {\sum\limits_{n = - N/2 + 1}^{N/2} {{M_{{\rm{hydr}}}}F\left( {{K_{xm}},{K_{yn}}} \right)} }\times \\ &\exp \left[ {{\rm{i}}\left( {{K_{{\text{x}}m}}x + {K_{yn}}y} \right) - {\rm{i}}{\omega _{mn}}t} \right] \Biggr\}.\\[-20pt]\end{split} $$ | (11) |

In the traditional two-scale model, the scattering coefficient

| $$ {S_l} = {S_x}\cos {\varphi _i} + {S_y}\sin {\varphi _i} = \frac{{\partial {Z_l}}}{{\partial x}}\cos {\varphi _i} + \frac{{\partial {Z_l}}}{{\partial y}}\sin {\varphi _i} , $$ | (12) |

where

Doppler centroid frequency shift

| $$ {f_M} = \frac{{\displaystyle\sum\limits_{m = - M/2 + 1}^{M/2} \;\;{\sum\limits_{n = - N/2 + 1}^{N/2} {{\sigma _{{\text{PP}}}}({{\theta '}_i}){f_{mn}}} } }}{{\displaystyle\sum\limits_{m = - M/2 + 1}^{M/2} \;{\sum\limits_{n = - N/2 + 1}^{N/2} {{\sigma _{{\text{PP}}}}({{\theta '}_i})} } }} , $$ | (13) |

with

| $$ {f_{mn}} = \frac{{{k_{\rm{e}}}}}{\pi }({V_z}_{mn}\cos {\theta _i} + {V_x}_{mn}\sin {\theta _i}\cos {\varphi _i} + {V_y}_{mn}\sin {\theta _i}\sin {\varphi _i}) , $$ | (14) |

where the velocities

| $$ {f_{\text{D}}} = {f_{\text{M}}} + {f_{\text{B}}} + {f_{{\text{drift}}}} , $$ | (15) |

with

| $$ {f_{{\text{drift}}}}{\text{ = }}\frac{1}{{2\pi }}{{\boldsymbol{U}} _{{\text{drift}}}} \cdot {{\boldsymbol{K}} _{\text{B}}} , $$ | (16) |

| $$ {f_{\text{B}}} = \frac{1}{{2\pi }}\sqrt {g\left| {{{\boldsymbol{K}} _{\text{B}}}({\theta _i})} \right|} \left[ {F\left( {{K_{\text{B}}},{\phi _{\text{B}}}} \right) + F\left( {{K_{\text{B}}},{\phi _{\text{B}}} + \pi } \right)} \right] , $$ | (17) |

where the wind drift

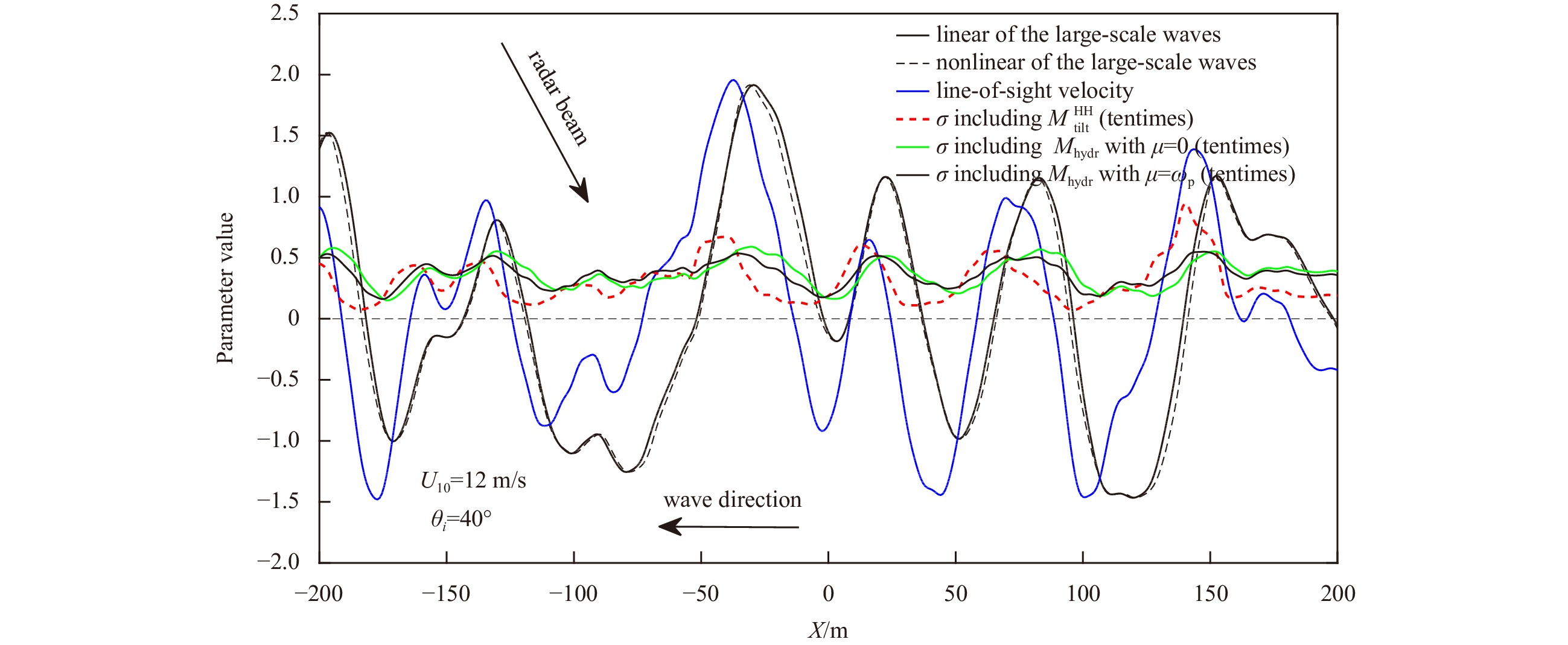

From Eqs (13) and (14) we can find that the predicted Doppler centroid frequency shift would be affected by the locally-modulated radar cross section and the orbital motions of the large-scale waves. Figure 1 illustrates the simulated profiles of the nonlinear surface and the linear surface. Here, the wind speed is

In the two-scale model, how to set the cut-off wavenumber

In upwind and downwind directions, the influences of the incidence angle on the Doppler shifts predicted by the TSM are presented in Fig. 3. When the wind speed is 10 m/s, the absolute value of the Doppler shift in upwind direction is always larger than that in downwind direction within the range of medium incidence angle. The numerical results in Wang et al. (2012) showed that the horizontal-skewness of the large-scale waves would induce this difference. As shown in Fig. 1, the scattering coefficient from the local water surface would be modulated by the tilt and the hydrodynamic modulations of the large-scale waves. Because Doppler shifts are weighted by the power of the scattering field, thus the tilt and the hydrodynamic modulations would induce effects on the difference between the absolute values of the Doppler shifts in upwind and downwind directions. The curves in Wang et al. (2016) (Fig. 4 in Wang et al. (2016)) demonstrate that the value of the Doppler shift difference between upwind and downwind directions varies regularly with the relaxation rate for various wind speeds. With the increase of the relaxation rate, this difference gradually increases firstly until reaching the max maximum value, and then decreases with a relative smaller rate. Up to now, however, the relaxation rate is poorly known experimentally. Moreover, the values estimated by various investigators differ by almost one order of magnitude (Caponi et al., 1988). In Caponi et al. (1988), for moderate wind speeds, the value of the relaxation rate is 0.1 s−1 for L-band radar wave, and 1.7 s−1 for X-band radar wave. For C-band radar wave, the relaxation rate obtained by interpolating the values corresponding to L-band and X-band microwaves is 0.92 s−1, which is close to the angular frequency ωp of the dominate wave. Therefore, in this work, the value of the relaxation rate is set to be ωp.

For comparisons, the predicted Doppler shifts when the CSAR model is replaced by the traditional Bragg scattering coefficient are also shown in Fig. 3. In the incidence angle range of 25° to 45°, the absolute values of the Doppler shifts for upwind and downwind directions decrease with the incidence angle. Moreover, the Doppler shifts based on the CSAR model are usually larger than those obtained based on the traditional Bragg theory, except at smaller or larger incidence angles for HH-polarization case. In order to further explain the reason for the difference between the Doppler shifts corresponding to the experimental CSAR model and the traditional Bragg theory, the tilt modulation-transfer functions (MTFs) evaluated by CSAR model and by Bragg theory are shown in Fig. 4. Here, the experimental tilt MTFs for the CSAR model are calculated by

| $$ {{M}}_{{\rm{tilt\_e}}}^{{\text{HH}}}\left( {{\boldsymbol{U}},{\theta _i},{\phi _i}} \right) = {\rm{i}}{k_l}\frac{1}{{\sigma _{{\text{HH}}}^{{e}}\left( {{\boldsymbol{U}},{\theta _i},{\phi _i}} \right)}}{\left. {\frac{{\partial \sigma _{{\text{HH}}}^{{e}}}}{{\partial \theta }}} \right|_{\theta = {\theta _i},\;\phi = {\phi _i}}} , $$ | (18) |

and

| $$ {{M}}_{{\rm{tilt\_e}}}^{{\text{VV}}}\left( {{\boldsymbol{U}},{\theta _i},{\phi _i}} \right) = {\rm{i}}{k_l}\frac{1}{{\sigma _{{\text{VV}}}^{{e}}\left( {{\boldsymbol{U}},{\theta _i},{\phi _i}} \right)}}{\left. {\frac{{\partial \sigma _{{\text{VV}}}^{{e}}}}{{\partial \theta }}} \right|_{\theta = {\theta _i},\;\phi = {\phi _i}}} . $$ | (19) |

where

The theoretical tilt MTFs derived based on the Bragg resonance theory for HH and VV polarizations are written as (Lyzenga, 1986; Hasselmann and Hasselmann, 1991)

| $$ {M}_{{\text{tilt}}}^{{\text{HH}}} = 8{\rm{i}}{k_l}{(\sin 2\theta )^{ - 1}} , $$ | (20) |

and

| $$ {M}_{{\text{tilt}}}^{{\text{VV}}} = 4{\rm{i}}{k_l}\cot \theta {(1 + {\sin ^2}\theta )^{ - 1}} . $$ | (21) |

In order to make the theoretical tilt MTFs and the experimental tilt MTFs comparable, in Fig. 4, the values of the tilt MTFs have been normalized with

The effects of different factors on the predicted Doppler shift are presented in Fig. 5. From the results we can find that the Doppler shifts due to the phase velocity of the Bragg of resonant wave, surface drift current, as well as the hydrodynamic modulation of large-scale waves have nothing to do with radar polarization. However, the Doppler shifts caused by the tilt modulations are significantly influenced by radar polarization. And the absolute value of Doppler shift for HH polarization is obvious larger than that corresponding to VV polarization. These differences can be attributed to the fact that the radar signals in HH polarization are more sensitive to the slope of large scale waves than in VV polarization. The comparison between the curves in Figs 5a and b demonstrate that the absolute values of the predicted Doppler shift corresponding to each factor increases with wind speed. On the other hand, the predicted Doppler shifts are all sensitive to the azimuth angle. As anticipated, when the azimuth angle of the radar beam is 90° or 270° (the cross-wind direction), the Doppler shifts due to different factors are all equal to zero, when the radar beam is directed toward the wind direction (upwind), the Doppler shifts are positive whereas they change sign under downwind conditions. Meanwhile, the Doppler shifts corresponding to the tilt and the hydrodynamic modulations show the asymmetries between upwind and downwind observations.

In order to verify Doppler shift predicted by the TSM model with, the Doppler centroid frequency shift predicted by the CDOP (Mouche et al., 2012), which is an empirical model for C-band echoes backscattered from sea surface, are also given out for comparison in Figs 6 and 7. In Fig. 6, the wind speed is 10 m/s. At different incidence angles, from the comparisons we can find that the predicted Doppler shifts by the TSM are generally in good agreement with the CDOP predictions. What’s more, the TSM model with

Figure 9 shows the comparison of Doppler shift results between our model (TSM model), CDOP and an updated GMF CDOP-3SiX (Moiseev et al., 2022) for different wind speeds and wind directions between 0° (upwind) and 180° (downwind) at two incidence angle 36° (top row) and 44° (bottom row). By comparing the results between three models for 3 m/s wind speed (left column) at both 36° and 44° incidence angles, the values of our model are closer to the CDOP-3SiX model, comparatively, the CDOP model significantly overestimate the Doppler shifts results at such a low wind speed. When the wind speed is 6 m/s (middle column), the results of three models are similar. When the wind speed reaches 12 m/s (right column), the values of the Doppler shift evaluated by our model near upwind and downwind directions are larger than the results of other two models, possibly because the modulations in the TSM model are somewhat larger than actual values at high wind speeds.

In order to facilitate the application, a fitting model can be applied to give the function relation between the values of the Doppler shift and the incidence angle, wind speed and wind direction. The fitting formulas based on the Doppler shift predicted by numerical TSM model for HH and VV polarizations can be decomposed as a harmonic expressions (hereinafter referred to as CSAR-DOP), i.e.,

| $$ \begin{split}f\; _{\rm{D}}^{{\rm{PP}}}\left( {\theta ,\phi ,{U_{10}}} \right) = C_1^{{\rm{PP}}}\left( {\theta ,{U_{10}}} \right)\cos \left( \phi \right) + C_2^{{\rm{PP}}}\left( {\theta ,{U_{10}}} \right)\left( {1 + \cos \left( {2\phi } \right)} \right),\end{split} $$ | (22) |

where, the coefficients

| $$ C_1^{{\rm{PP}}}\left( \theta \right) = \frac{{f\;_{\rm{D}}^{{\rm{PP}}}\left( {\theta ,0} \right) - f\;_{\rm{D}}^{{\rm{PP}}}\left( {\theta ,\pi } \right)}}{2} , $$ | (23) |

| $$ C_2^{{\rm{PP}}}\left( \theta \right) = \frac{{f\;_{\rm{D}}^{{\rm{PP}}}\left( {\theta ,0} \right) + f\;_{\rm{D}}^{{\rm{PP}}}\left( {\theta ,\pi } \right)}}{4} . $$ | (24) |

The polynomial fitting formulas of the coefficients

In this work, we have presented a numerical method based on the TSM and nonlinear sea wave model for predicting the Doppler shift of C-band echoes backscattered from ocean surface at moderate incident angle. Based on the numerical method, the factors and the mechanisms affecting the Doppler frequency shift of sea surface echoes are analyzed in detail. From the predicted Doppler shifts, we can firstly find that the Doppler shifts would be obviously affected by the tilt modulation of the large scale waves. And the Doppler shift for HH polarization is always larger than that for VV polarization just due to the tilt modulation. Secondly, at moderate incidence angles, the difference between the Doppler shift predicted in upwind and downwind direction is mainly affected by the hydrodynamic modulation of the large-scale waves. Compared with the Doppler shift evaluated by the CDOP model, more reasonable Doppler shift at upwind and downwind directions can be predicted by the TSM model at lower wind speeds. Moreover, the Doppler shift results of TSM model under low wind speeds are also found to agree with the CDOP-3SiX. At the end of this work, to facilitate the application, the semi-empirical Doppler shift model (CSAR-DOP) for HH and VV polarization cases have been developed on the basis of the polynomial fitting method. The comparison between the Doppler shifts predicted by TSM and by CSAR-DOP illustrate that CSAR-DOP model can be used to predict the Doppler shift.

|

Alpers W R, Ross D B, Rufenach C L. 1981. On the detectability of ocean surface waves by real and synthetic aperture radar. Journal of Geophysical Research, 86(C7): 6481–6498. doi: 10.1029/JC086iC07p06481

|

|

Apel J R. 1994. An improved model of the ocean surface wave vector spectrum and its effects on radar backscatter. Journal of Geophysical Research, 99(C8): 16269–16291. doi: 10.1029/94JC00846

|

|

Barrick D E. 1977. Extraction of wave parameters from measured HF radar sea-echo Doppler spectra. Radio Science, 12(3): 415–424. doi: 10.1029/RS012i003p00415

|

|

Bass F G, Fuks I, Kalmykov A I, et al. 1968. Very high frequency radiowave scattering by a disturbed sea surface Part II: scattering from an actual sea surface. IEEE Transactions on Antennas and Propagation, 16(5): 560–568. doi: 10.1109/TAP.1968.1139244

|

|

Caponi E A, Crawford D R, Yuen H C, et al. 1988. Modulation of radar backscatter from the ocean by a variable surface current. Journal of Geophysical Research, 93(C10): 12249–12263. doi: 10.1029/JC093iC10p12249

|

|

Chapron B, Collard F, Ardhuin F. 2005. Direct measurements of ocean surface velocity from space: interpretation and validation. Journal of Geophysical Research, 110(C7): C07008

|

|

Chen K S, Fung A K, Amar F. 1993. An empirical bispectrum model for sea surface scattering. IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing, 31(4): 830–835. doi: 10.1109/36.239905

|

|

Crombie D D. 1955. Doppler spectrum of sea echo at 13.66Mc./s. Nature, 175(4459): 681–682. doi: 10.1038/175681a0

|

|

Elfouhaily T, Chapron B, Katsaros K, et al. 1997. A unified directional spectrum for long and short wind-driven waves. Journal of Geophysical Research, 102(C7): 15781–15796. doi: 10.1029/97JC00467

|

|

Fuks I M, Voronovich A G. 2002. Radar backscattering from Gerstner’s sea surface wave. Waves in Random Media, 12(3): 321–339. doi: 10.1088/0959-7174/12/3/305

|

|

Fung A K. 1994. Microwave Scattering and Emission Models and Their Applications. Norwood: Artech House

|

|

Hasselmann K, Hasselmann S. 1991. On the nonlinear mapping of an ocean wave spectrum into a synthetic aperture radar image spectrum and its inversion. Journal of Geophysical Research, 96(C6): 10713–10729. doi: 10.1029/91JC00302

|

|

Hayslip A R, Johnson J T, Baker G R. 2003. Further numerical studies of backscattering from time-evolving nonlinear sea surfaces. IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing, 41(10): 2287–2293. doi: 10.1109/TGRS.2003.814662

|

|

Johannessen J A, Kudryavtsev V, Akimov D, et al. 2005. On radar imaging of current features: 2. Mesoscale eddy and current front detection. Journal of Geophysical Research, 110(C7): C07017

|

|

Johnson J T, Burkholder R J, Toporkov J V, et al. 2009. A numerical study of the retrieval of sea surface height profiles from low grazing angle radar data. IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing, 47(6): 1641–1650. doi: 10.1109/TGRS.2008.2006833

|

|

Johnson J T, Toporkov J V, Brown G S. 2001. A numerical study of backscattering from time-evolving sea surfaces: comparison of hydrodynamic models. IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing, 39(11): 2411–2420. doi: 10.1109/36.964977

|

|

Karaev V, Kanevsky M, Meshkov E. 2008. The effect of sea surface slicks on the Doppler spectrum width of a backscattered microwave signal. Sensors, 8(6): 3780–3801. doi: 10.3390/s8063780

|

|

Keller W C, Plant W J, Alenzuela G R. 1986. Observation of breaking ocean waves with coherent microwave radar. In: Phillips O M, Hasselmann K, eds. Wave Dynamics and Radio Probing of the Ocean Surface. Boston: Springer, 285–293

|

|

Kudryavtsev V, Akimov D, Johannessen J, et al. 2005. On radar imaging of current features: 1. Model and comparison with observations. Journal of Geophysical Research, 110(C7): C07016

|

|

Leykin I A, Donelan M A, Mellen R H, et al. 1995. Asymmetry of wind waves studied in a laboratory tank. Nonlinear Processes in Geophysics, 2(3): 280–289. doi: 10.5194/npg-2-280-1995

|

|

Li Xiaoming, Lehner S. 2014. Algorithm for sea surface wind retrieval from TerraSAR-X and TanDEM-X Data. IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing, 52(5): 2928–2939. doi: 10.1109/TGRS.2013.2267780

|

|

Lindgren G. 2009. Exact asymmetric slope distributions in stochastic Gauss-Lagrange ocean waves. Applied Ocean Research, 31(1): 65–73. doi: 10.1016/j.apor.2009.06.002

|

|

Lindgren G, Åberg Sofia. 2009. First order stochastic Lagrange model for asymmetric ocean waves. Journal of Offshore Mechanics and Arctic. Engineering, 131(3): 031602

|

|

Lipa B. 1978. Inversion of second-order radar echoes from the sea. Journal of Geophysical Research, 83(C2): 959–962. doi: 10.1029/JC083iC02p00959

|

|

Lyzenga D R. 1986. Numerical simulation of synthetic aperture radar image spectra for ocean waves. IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing, GE-24(6): 863–872. doi: 10.1109/TGRS.1986.289701

|

|

Moiseev A, Johannessen J A, Johnsen H. 2022. Towards retrieving reliable ocean surface currents in the coastal zone from the sentinel-1 Doppler shift observations. Journal of Geophysical Research, 127(5): e2021JC018201

|

|

Moiseev A, Johnsen H, Johannessen J A, et al. 2020. On removal of sea state contribution to Sentinel-1 Doppler shift for retrieving reliable ocean surface current. Journal of Geophysical Research, 125(9): e2020JC016288

|

|

Mouche A, Chapron B. 2015. Global C-Band Envisat, RADARSAT-2 and Sentinel-1 SAR measurements in copolarization and cross-polarization. Journal of Geophysical Research, 120(11): 7195–7207. doi: 10.1002/2015JC011149

|

|

Mouche A A, Chapron B, Reul N, et al. 2008. Predicted Doppler shifts induced by ocean surface wave displacements using asymptotic electromagnetic wave scattering theories. Waves in Random and Complex Media, 18(1): 185–196. doi: 10.1080/17455030701564644

|

|

Mouche A A, Collard F, Chapron B, et al. 2012. On the use of Doppler shift for sea surface wind retrieval from SAR. IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing, 50(7): 2901–2909. doi: 10.1109/TGRS.2011.2174998

|

|

Shao Weizeng, Zhang Zheng, Li Xiaoming, et al. 2016. Sea surface wind speed retrieval from TerraSAR-X HH polarization data using an improved polarization ratio model. IEEE Journal of Selected Topics in Applied Earth Observations and Remote Sensing, 9(11): 4991–4997. doi: 10.1109/JSTARS.2016.2590475

|

|

Tayfun M A. 1986. On narrow-band representation of ocean waves: 1. Theory. Journal of Geophysical Research, 91(C6): 7743–7752. doi: 10.1029/JC091iC06p07743

|

|

Toporkov J V, Brown G S. 2000. Numerical simulations of scattering from time-varying, randomly rough surfaces. IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing, 38(4): 1616–1625. doi: 10.1109/36.851961

|

|

Verspeek J, Stoffelen A, Verhoef A, et al. 2012. Improved ASCAT wind retrieval using NWP ocean calibration. IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing, 50(7): 2488–2494. doi: 10.1109/TGRS.2011.2180730

|

|

Wang Yunhua, Zhang Yanmin. 2011. Investigation on Doppler shift and bandwidth of backscattered echoes from a composite sea surface. IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing, 49(3): 1071–1081. doi: 10.1109/TGRS.2010.2070071

|

|

Wang Yunhua, Zhang Yanmin, Guo Lixin. 2013. Microwave Doppler spectra of sea echoes at high incidence angles: influences of large-scale waves. Progress in Electromagnetics Research B, 48: 99–113. doi: 10.2528/PIERB12123004

|

|

Wang Yunhua, Zhang Yanmin, He Mingxia, et al. 2012. Doppler spectra of microwave scattering fields from nonlinear oceanic surface at moderate- and low-grazing angles. IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing, 50(4): 1104–1116. doi: 10.1109/TGRS.2011.2164926

|

|

Wang Yunhua, Zhang Yanmin, Li Huimin, et al. 2016. Doppler spectrum of microwave SAR signals from two-dimensional time-varying sea surface. Journal of Electromagnetic Waves and Applications, 30(10): 1265–1276. doi: 10.1080/09205071.2016.1186575

|

|

Wright J W, Keller W C. 1971. Doppler spectra in microwave scattering from wind waves. The Physics of Fluids, 14(3): 466–474. doi: 10.1063/1.1693458

|

|

Zavorotny V U, Voronovich A G. 1998. Two-scale model and ocean radar Doppler spectra at moderate- and low-grazing angles. IEEE Transactions on Antennas and Propagation, 46(1): 84–92. doi: 10.1109/8.655454

|