| Citation: | Guiyuan Dai, Guizhi Wang, Qing Li, Weizhen Jiang, Fei Zhang. Optimization of enrichment and pretreatment of low-activity radium isotopes in the open ocean[J]. Acta Oceanologica Sinica, 2023, 42(8): 171-177. doi: 10.1007/s13131-023-2152-3 |

Radium (Ra) is a naturally occurring radioactive element with four isotopes, 223Ra (half-life=11.4 d), 224Ra (half-life=3.66 d), 226Ra (half-life=1600 a), and 228Ra (half-life=5.75 a). Radium quartet has been widely employed in tracing submarine groundwater discharge and estimating residence time on nearshore, embayment, and shelf scales (Moore, 1996; Charette et al., 2003; Wang et al., 2014, 2015, 2018; Tan et al., 2018; Zhang et al., 2020). The long-lived radium isotopes, 226Ra and 228Ra, have been used to trace water masses and to estimate vertical and horizontal mixing rates in the open ocean (Moore, 1972; Trier et al., 1972; Sanial et al., 2018). However, 228Ra activities in the open ocean are usually a few Becquerel per cubic metre (Ku et al., 1970; Charette et al., 2015; Kipp et al., 2018), in contrast to tens of Becquerel per cubic metre in coastal and shelf regions. Large volumes of seawater, several hundred liters, are, therefore, demanded to determine the activity of radium in the open ocean waters due to the relatively low detection efficiency of commonly used gamma counters. Thus, limited by ship-time consuming collection of radium samples, short-lived radium isotopes in the open ocean, especially from deep below the surface, are rarely reported (Charette et al., 2015; Kipp et al., 2018).

In 1969, Moore presented a method of measuring 228Ra in the seawater using a β counter via enrichment of radium by coprecipitation with BaSO4. His method required hundreds of liters of seawater for radium to be detectable and was too complicated to apply onboard (Trier et al., 1972; Kaufman et al., 1973). Then Moore and Reid (1973) found that MnO2-coated acrylic fibers performed well in scavenging radium from seawater at a relatively low flowing-through rate (<1 L/min). When sampling in the field, the MnO2-coated acrylic fibers had to be soaked in a predetermined position and it was difficult to determine the sampling volume (Moore, 1976). Moreover, such sampling was extremely time-consuming. Later on, in situ pumps were developed to extract radium at depth with Mn-impregnated acrylic cartridges at a relatively high flow rate, 5–10 L/min, (Michel et al., 1981). After enrichment of radium on the cartridge there are two ways of pretreatments in the laboratory. One is leaching the cartridge with hydrochloric acid (HCl) or nitric acid (HNO3) to recover the radium adsorbed on the cartridge (Moore, 1969). This pretreatment, however, was time-consuming with relatively low radium recovery. The other is ashing the cartridge and transferring the ash to a measurement vial (Henderson et al., 2013).

Therefore, MnO2-coated cartridges installed on in situ pumps have been widely used to extract radium from open-ocean seawaters and ashing has been a common pretreatment practice (Henderson et al., 2013; Charette et al., 2015; Sanial et al., 2018).

However, when we tested these procedures in our lab, some issues arose. Firstly, it was not easy to make MnO2 evenly impregnated on the cartridge. Secondly, the long overnight baking time (about 48 h) was time-consuming. Thirdly, there was an ash loss when transferring the ash to a measurement vial. Lastly, the weight of the ash varied greatly from 1.7 g to 12.4 g, which would result in a change by 25% in the measurement efficiency of a gamma detector (Henderson et al., 2013). To address these issues, in this study, we aimed to optimize the methods of low-activity radium enrichment and pretreatment.

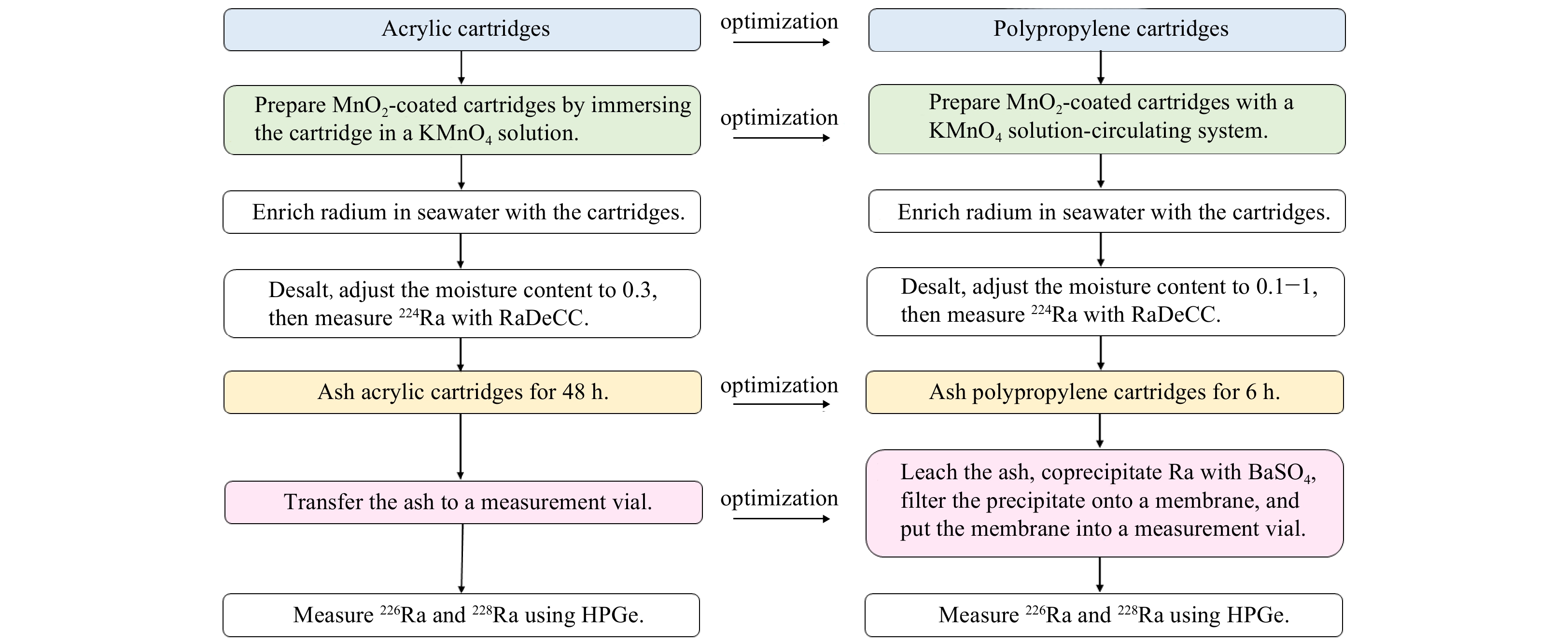

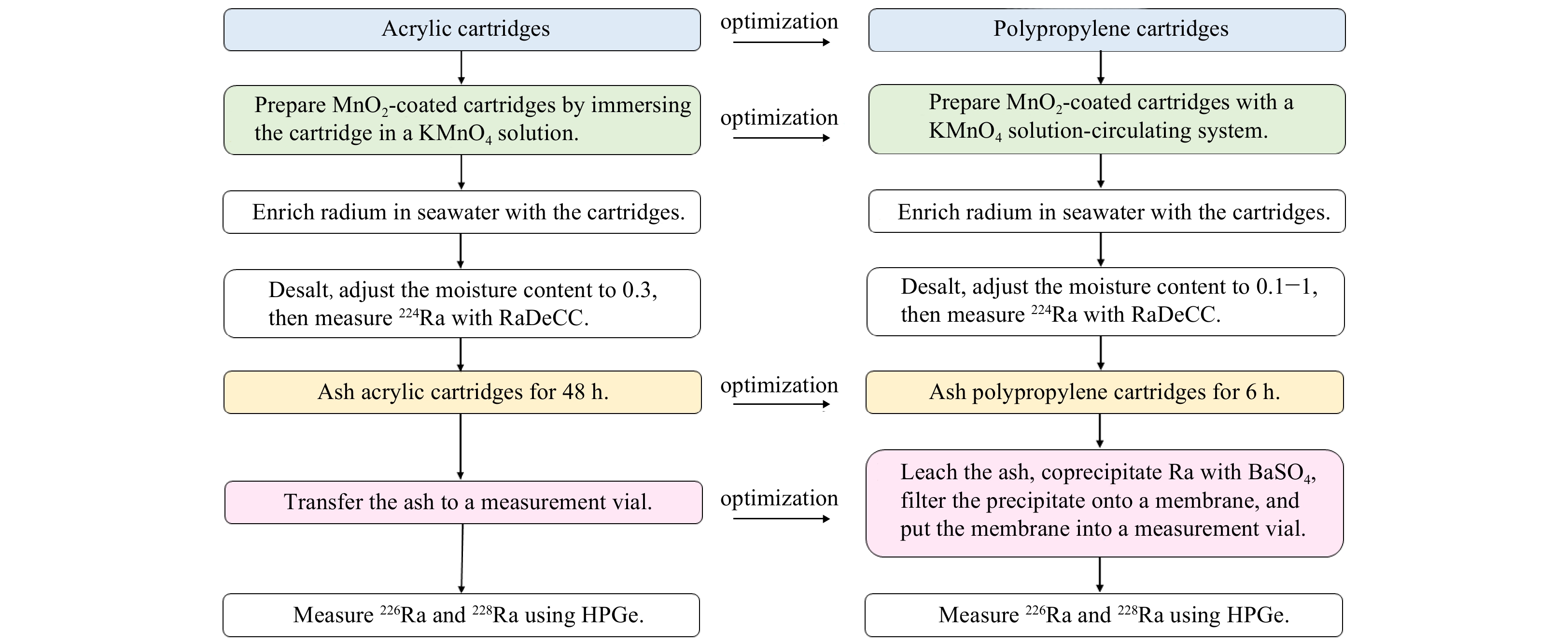

As shown in Fig. 1, our optimization of low-activity radium enrichment and pretreatment procedures include a change of the cartridge material, a design of a circulation coating system, and an additional treatment of the ashed cartridge. Briefly, we replaced acrylic cartridges with polypropylene cartridges and designed a KMnO4 solution-circulating system to coat MnO2 on the cartridge. In addition, the MnO2-coated cartridges were pretreated after ashing with leaching and coprecipitation of radium with BaSO4 prior to measurements.

We dissolved 474 g KMnO4 (Xilong Scientific, China) in 5 L Reverses Osmosis (RO) pure water at room temperature and diluted 60 mL concentrated H2SO4 (Guaranteed Reagent, Sinopharm Chemical Reagent, China) with 1 L pure water. Then the KMnO4 solution was mixed with the diluted H2SO4 solution in a beaker (5 L) to get a hot (70–80℃) acidic (1%, v/v) KMnO4 solution (0.5 L/min). The beaker with KMnO4 solution was put in the water bath (HH-8, Bangxi, China) to keep the temperature at 70–80℃. A blank cartridge (5 inches high, 5 mm in pore size, 60 mm in diameter, and made of polypropylene by Huamo Co., China) was put into a matching holder (Mianyang SINOMIX, China) and the hot acidic KMnO4 solution circulated through the cartridge continuously with a submersible pump (JP-064, SUNSUN, China) (Fig. S1). About an hour later, the cartridge was turned upside down to ensure an even coating of the cartridge with MnO2. Two and a half hours later, the circulation was stopped, and the holder was taken out. The cartridge was washed by connecting the inlet and outlet, respectively, of the holder to pure water until the water through the cartridge was colorless. The washing process took about 2 h. Then the cartridge was dried, which took about 2 d, and packed in a zip-lock bag. The entire process, including coating, washing and drying cartridges usually took more than 2 d.

To determine low-activity radium isotopes in the open ocean, in situ pumps (McLANE, America, Water Transfer System L V S/N: 11721) with MnO2-coated cartridges were used to enrich radium. The flow rate of the in situ pump ranged from 4 L/min to 7 L/min. After enrichment of radium, the MnO2-coated cartridge was washed with RO water at least three times as much as the volume of the cartridge holder to desalt thoroughly (Sun and Torgersen, 1998). And the moisture content (the mass ratio of the water to the MnO2-coated cartridge) of the MnO2-coated cartridge was adjusted to 0.05–1 with an air pump (ACO-003, SUNSUN, China). Then 224Ra absorbed by MnO2-coated cartridges was measured using a radium delayed coincidence counter (RaDeCC).

After the measurement of224Ra, the MnO2-coated cartridges were measured for 226Ra and 228Ra with a high purity germanium gamma spectrometer (HPGe) (GCW4023, Canberra, America). Firstly, the MnO2-coated cartridge was ashed in a muffle furnace (KSL-1200X-M, Kejing, China) at 820℃ for 6 h (Fig. 2a). The ash (Fig. 2b) was then leached with about 250 mL (more was used if necessary) heated (80–90℃) mixture of 1 mol/L hydroxylamine hydrochloride (Xilong, China) and 1 mol/L HCl (Guaranteed Reagent, Sinopharm Chemical Reagent, China) at a ratio of 2:1 until the ash was completely dissolved (Fig. 2c). After leaching, the mixture was diluted to about 600 mL with RO water, followed by coprecipitating radium in the solution with BaSO4 (with 25 mL 1 mol/L NaHSO4 (Xilong, China) and 5 mL saturated Ba(NO3)2 (Xilong, China) added to the solution, which was then stirred with a glass rod until the precipitate was formed and the bottom was not seen). After standing for 12 h, the precipitate was filtered onto a 0.45 μm (smaller than the particle size of BaSO4) cellulose acetate membrane, which was folded and put in a 10 mL centrifugal vial and RO water was added to the scale of 4 mL (Fig. 2d). The vial was then sealed with parafilm for three weeks before being measured for 226Ra and 228Ra (Fig. 2e).

Henderson et al. (2013) suggested that an acrylic grooved cartridge (13 cm high) made by 3M Co. with a 48 h soaking period performed well in radium extraction. However, the acrylic grooved cartridge is relatively expensive. We replaced the acrylic cartridge with a cheaper polypropylene cartridge made in China (as described in Section 2.1).

To prepare MnO2 impregnated cartridges, we immersed the polypropylene cartridge in 0.5 mol/L acidic KMnO4 solution at 70℃ to 80℃ according to Henderson et al. (2013), and the soaking time was extended from 45 min based on Henderson et al. (2013) to more than 13 h. Unfortunately, only 0.7 g MnO2 was coated on the surface of this cartridge and internal adsorption of MnO2 was scarce (Fig. 3a). To address this uneven coverage issue, we developed a circulation system to allow MnO2 to adsorb on the cartridge homogeneously in 2.5 h (Fig. S1). Using this system, about 10 g MnO2 was adsorbed on the cartridge from inside out (Fig. 3b). The radium extraction efficiencies of the cartridge immersed in the KMnO4 solution for about 10 h (Fig. 3a) were 56%, 64% and 67% for 224Ra, 226Ra and 228Ra, respectively, which were only equivalent to 62%–83% of that of the cartridge made using the circulation system (Fig. 3b).

RaDeCC has been widely used as a convenient instrument to measure 223Ra and 224Ra (Rama et al., 1987; Moore and Arnold, 1996; Moore, 2008; Wang et al., 2015, 2018). After sampling, the initial 224Ra, including excess 224Ra and 224Ra supported by 228Th, was measured within 1–3 d. A month later, 224Ra supported by 228Ra was measured. The initial 223Ra (including excess 223Ra and 223Ra supported by 227Ac) measurement was conducted within 7–10 d after sampling. 223Ra supported by 227Ac was measured in two months. Therefore, excess 223Ra and 224Ra were obtained through 4 measurements (Moore, 2008). The details of calculating the excess 223Ra and 224Ra can be found in Moore and Arnold (1996) and Moore (2008). In this study, the 224Ra standard for the MnO2-coated fiber and MnO2-coated cartridge was supported by its parent 228Th. Similar to the measurement of 223Ra and 224Ra on the MnO2-coated fiber (Moore and Arnold, 1996), short-lived radium isotopes adsorbed by MnO2-coated cartridges were also measured using RaDeCC. But the detector efficiency for MnO2-coated cartridges was different from that for MnO2-coated fibers due to shape difference, which caused difference in sweeping efficiencies of alpha particles. To determine the RaDeCC efficiency for MnO2-coated cartridges, four cartridge standards for 224Ra were made. Because stock solution of 227Ac was not available, the standard for 223Ra was not discussed in this study. The activity of 232U stock solution (equilibrated with daughters 228Th and 224Ra), which was used for 224Ra calibration, is (4.15±0.03) Bq/g. The 232U solution was diluted with about 2 L Ra-free seawater, and was then circulated through a MnO2-coated cartridge driven by a peristaltic pump (07554-95, Cole-Parmer, America) for 1 h. The Ra-free seawater was made using surface seawater collected in the South China Sea in the summer of 2018, with a salinity of 33.2 and a temperature of 19.5℃, and MnO2-coated fibers. Then the cartridge was washed well with 1 L RO water to remove the salt. The residual liquid from diluted 232U solution and washed RO water were merged and flowed through 16 g MnO2-coated fibers at a flow rate less than 1 L/min to enrich radium (Moore, 1976). The MnO2-coated fiber (with a mass ratio of water to fiber of 1) was immediately measured with RaDeCC to determine how much radium was not adsorbed on the MnO2-coated cartridge. The radium on the MnO2-coated fiber was below the detection limit, suggesting there was no radium in the residual liquid and washed RO water. Then the cartridge was stored in a zip-lock bag, waiting to be checked for temporal stability.

The relative standard deviation (RSD), which is the ratio of the standard deviation to the average, of the cartridge standard was used to test if the cartridge standard was stable based on the RSD of the fiber standard. In our laboratory, the MnO2-coated fiber standard for 224Ra used for RaDeCC, which was from Willard S. Moore, University of South Carolina, has been used for more than 10 a and is stable. The fiber standard with moisture content of 1.0 was measured for a week to test the stability of RaDeCC (Fig. S2). Four RaDeCC systems were tested and the fiber standard was measured with each system for about 300 min once a day. In the first 100 min, the efficiency varied greatly until about 200 min. Thus, we suggest that the fiber standard should be measured for at least 200 min. Moreover, the efficiency varied among the four systems. The efficiency of System 2 was the lowest, 0.441±0.003, while System 4 had the highest efficiency, 0.520±0.005. For Systems 1 and 3, the efficiencies were 0.499±0.008 and 0.509±0.008, respectively. The RSD of the fiber standard measured with the four systems was no more than 0.02 (Fig. S2). So, we assume the cartridge standard is practically stable if the RSD of the cartridge standard is less than 0.02.

Six months later, the four cartridge standards were measured with RaDeCC Systems 1, 2, 3, and 4 (Fig. 4). The RaDeCC efficiency varied slightly for the same RaDeCC system. The RaDeCC efficiency varied from 0.279 to 0.295, with an average of 0.284±0.005 for RaDeCC System 1, from 0.251 to 0.262, with an average of 0.257±0.003 for RaDeCC System 2, from 0.323 to 0.336, with an average of 0.331±0.004 for RaDeCC System 3, and from 0.304 to 0.320, with an average of 0.310±0.005 for RaDeCC System 4 (Fig. 4). All the RSDs were no more than 0.02. Thus, the cartridge standards were stable. The RaDeCC efficiency for cartridges of the four systems was 0.257–0.331, 35%–43% lower than that for fibers. The lower RaDeCC efficiency for cartridges may be caused by the texture. The cartridge texture may influence the emanation efficiency of 220Rn (Sun and Torgersen, 1998).

The RaDeCC detector efficiency is the product of the cell efficiency, system efficiency and emanation efficiency (Sun and Torgersen, 1998). Changes in the sample shape (fiber or cartridge) will not influence the cell efficiency and system efficiency. Sun and Torgersen (1998) suggested that the emanation efficiency was related to the thickness of water film on the MnO2-coated fiber and that the RaDeCC efficiency for MnO2-coated fibers was the highest at a water content of 0.3–1. We, thus, deduced that the RaDeCC efficiency for MnO2-coated cartridges might be also affected by the moisture content of the cartridge. To determine a proper moisture content for the MnO2-coated cartridge, the moisture content of the cartridge standards was adjusted by sprinkling water or ventilating in a clean hood, and then left for a week to reach stability. First, we started with a moisture content of approximately 1 to avoid the water being carried into the scintillation cell. After measurements, the standards were placed in a clean hood to lower the moisture content by about 5%, then measuring and lowering moisture content until the moisture content of the cartridge standards reached 0. As shown in Fig. 5, when the moisture content ranged from 0.04 to 1.04, the RaDeCC detector efficiency of System 3 for Cartridge Standard 1 fluctuated slightly, from 0.322 to 0.355 (with an average of 0.335±0.009 and RSD of 0.026). However, when the moisture content was less than 0.01, the efficiency showed a sharp decline to as low as 0.215 (Fig. 5a). The RaDeCC detector efficiency of System 4 for Cartridge Standard 2 showed a similar pattern with the efficiency in the range from 0.303 to 0.322 (with an average of 0.312±0.005 and RSD of 0.016) at a moisture content of 0.01−1.05 (Fig. 5b). As a result, with a moisture content of 0.05−1, the influence of moisture contents on the RaDeCC detector efficiency for cartridge standards was negligible.

After the measurement of224Ra, the MnO2-coated cartridges were measured for 226Ra and 228Ra. In the common method, the MnO2-coated acrylic cartridge was usually ashed at 820℃ for 48 h (Henderson et al., 2013; Charette et al., 2015; Kipp et al., 2018). Then the ash was transferred to polystyrene vials and sealed with epoxy resin before being measured using HPGe (Henderson et al., 2013). The details of long-lived radium measurement and calculation with HPGe can be found in Moore (1984). However, ashing overnights (48 h) was time-consuming. In addition, about 15% of ash is to be lost during transfer. And the weights of ash showed great variations, which can cause a change in the efficiency of HPGe of 25%. In our study, it took 6 h to completely ash the polypropylene cartridge, 42 h shorter than the acrylic cartridge. We did a comparative experiment using the acrylic cartridge and ashed for 6 h. The amount of ash of the acrylic cartridge was about a few times greater than that of our cartridge (Fig. S3). To avoid ash loss during transfer and the variation in the efficiency of HPGe caused by different ash weights, a pretreatment method was developed. The ashed cartridge was leached and radium was coprecipitated with BaSO4 with details described in Section 2.3.

Moore (1984) proposed a single factor (F) to convert cpm to dpm as below:

| $$ dpm =F\times cpm, $$ | (1) |

where dpm is a unit of radioactive activity, disintegrations per minute. And cpm is the count rate of the instrument, counts per minute. F is related to the sample geometry in the measurement vial. In order to determine F, 226Ra and 228Ra mixed standards were made. Weighed 226Ra and 228Ra standard solutions (National Institute of Metrology, China) were diluted to 600 mL and 226Ra and 228Ra were coprecipitated with BaSO4, then the precipitate was filtered, sealed in centrifuge tubes, and measured using HPGe. Duplicate mixed standards were made and measured three times, respectively. F was consistent for the duplicate standards (Table S1).

During ashing, leaching, coprecipitation, and filtration (Fig. 2), potential loss of radium may occur. To determine the recovery of 226Ra and 228Ra during these processes, three MnO2-coated cartridge standards were made in almost the same way as in the 224Ra standards preparation except that the long-lived radium isotopes in the residual liquid and washed RO water were coprecipitated with BaSO4, then sealed in a matching vial. Three weeks later, the vial with BaSO4 precipitates was put in HPGe to measure for 226Ra and 228Ra. No peaks were detected for the vial, suggesting that all the 226Ra and 228Ra were absorbed on the MnO2-coated cartridge. Three 226Ra and 228Ra cartridge standards were made and preprocessed as described in Section 2.3. The recovery ranged from 94% to 99% for 226Ra and from 100% to 102% for 228Ra (Table S2), greater than 85% in the study of Xie et al. (1994). We also conducted an experiment to test the recovery of direct transferring the ash to the measurement vial. After ashing, the weight of the ashed cartridge in the cup was 3.4 g. After being transferred from the cup to the measurement vial, 0.5 g ash was lost. The recovery of the transfer was thus 85%. This indicates that our approach improved the recovery by 11%.

Baskaran et al. (1993) revealed that the radium adsorption efficiency of the MnO2-coated cartridge depended on the distribution coefficient of radium between the seawater and the MnO2, the reaction rate between the radium and MnO2, and the flow rate that controls the contact time. The radium extraction efficiency of the MnO2-coated fiber was low at a flow rate greater than 1.5 L/min during sampling (Moore, 2008). As for MnO2-coated cartridges, however, they are installed in in situ pumps with a flow rate of 4–7 L/min during sampling. To evaluate the influence of flow rates on the radium extraction efficiency of the MnO2-coated cartridge, the nearshore seawater with different radium activities was pumped through a MnO2-coated cartridge with a flow jet at different flow rates (Table S3), followed by 16 g MnO2-coated fiber with a flow rate of less than 1 L/min (Fig. S4). Specific flow rates and the radium activities absorbed on cartridges and fibers were listed in Table S3. The 224Ra extraction efficiency decreased from 98% at 0.6 L/min to 73% at 7.8 L/min, then kept constant at around 77% (Fig. 6). Similar to the efficiency for 224Ra, the 228Ra extraction efficiency reduced from 100% to 79% with the flow rate changing from 0.6 L/min to 7.8 L/min, then kept constant at 82%. The extraction efficiency for 226Ra did not change much with flow rates, ranging from 75% to 83%. However, its peak was not observed at the lowest flow rate. Strangely, the extraction efficiency for 226Ra differed from those for 224Ra and 228Ra at 0.6–6.6 L/min for some reason that we have not figured out yet. To summarize, the in situ pump working flow rate, 4–7 L/min, contributed 3%–4% variation to the radium extraction efficiency of the MnO2-coated cartridge. The error in the extraction efficiency caused by the measurement error of radium ranged from 2% to 6% (Table S3). The uncertainty in the radium extraction efficiency caused by the flow rate fell in the range of this error.

In this study, we made improvements in enrichment and pretreatment of low-activity radium in the open ocean. Firstly, the commonly used acrylic cartridge was replaced by a cheaper polypropylene cartridge. Our cartridge took only 6 h to be ashed, much shorter than that for the acrylic cartridge. Secondly, a circulation system with a hot acidic KMnO4 solution was designed to coat the polypropylene cartridge with MnO2. In this way, a homogeneous coating was realized with a radium extraction efficiency 20%–61% higher than that of the commonly used direct immersion in the same solution. Thirdly, after ashing the cartridge, we leached the ash with a mixture of hydroxylamine hydrochloride and HCl, then coprecipitated radium with BaSO4 in order to avoid potential ash loss during transfer and the change in the efficiency of HPGe caused by the variation in the ash weight. The recovery of these processes ranged from 94% to 102%, which improves over those in previous studies.

Moreover, the RaDeCC efficiency was not sensitive to the moisture content of our MnO2-coated cartridge. Within the working flow rate of the in situ pump, about 4–7 L/min, the radium extraction efficiency of our MnO2-coated cartridge only varied from 3%–4%, well within the uncertainty resulting from the measurement errors.

Acknowledgements: We would like to thank Shilei Jin and Wen Lin for sampling. We thank Hotel Hongzhuancuo for providing the field experiment site.|

Baskaran M, Murphy D J, Santschi P H, et al. 1993. A method for rapid in situ extraction and laboratory determination of Th, Pb, and Ra isotopes from large volumes of seawater. Deep-Sea Research Part I: Oceanographic Research Papers, 40(4): 849–865. doi: 10.1016/0967-0637(93)90075-E

|

|

Charette M A, Morris P J, Henderson P B, et al. 2015. Radium isotope distributions during the US GEOTRACES North Atlantic cruises. Marine Chemistry, 177: 184–195. doi: 10.1016/j.marchem.2015.01.001

|

|

Charette M A, Splivallo R, Herbold C, et al. 2003. Salt marsh submarine groundwater discharge as traced by radium isotopes. Marine Chemistry, 84(1–2): 113–121

|

|

Henderson P B, Morris P J, Moore W S, et al. 2013. Methodological advances for measuring low-level radium isotopes in seawater. Journal of Radioanalytical and Nuclear Chemistry, 296(1): 357–362. doi: 10.1007/s10967-012-2047-9

|

|

Kaufman A, Trier R M, Broecker W S, et al. 1973. Distribution of 228Ra in the world ocean. Journal of Geophysical Research, 78(36): 8827–8848. doi: 10.1029/JC078i036p08827

|

|

Kipp L E, Sanial V, Henderson P B, et al. 2018. Radium isotopes as tracers of hydrothermal inputs and neutrally buoyant plume dynamics in the deep ocean. Marine Chemistry, 201: 51–65. doi: 10.1016/j.marchem.2017.06.011

|

|

Ku T L, Li Y H, Mathieu G G, et al. 1970. Radium in the Indian-Antarctic Ocean south of Australia. Journal of Geophysical Research, 75(27): 5286–5292. doi: 10.1029/JC075i027p05286

|

|

Michel J, Moore W S, King P T. 1981. γ-Ray spectrometry for determination of radium-228 and radium-226 in natural waters. Analytical Chemistry, 53(12): 1885–1889. doi: 10.1021/ac00235a038

|

|

Moore W S. 1969. Measurement of Ra228 and Th228 in sea water. Journal of Geophysical Research, 74(2): 694–704. doi: 10.1029/JB074i002p00694

|

|

Moore W S. 1972. Radium-228: Application to thermocline mixing studies. Earth and Planetary Science Letters, 16(3): 421–422. doi: 10.1016/0012-821X(72)90161-6

|

|

Moore W S. 1976. Sampling 228Ra in the deep ocean. Deep-Sea Research and Oceanographic Abstracts, 23(7): 647–651. doi: 10.1016/0011-7471(76)90007-3

|

|

Moore W S. 1984. Radium isotope measurements using germanium detectors. Nuclear Instruments and Methods in Physics Research, 223(2–3): 407–411

|

|

Moore W S. 1996. Large groundwater inputs to coastal waters revealed by 226Ra enrichments. Nature, 380(6575): 612–614. doi: 10.1038/380612a0

|

|

Moore W S. 2008. Fifteen years experience in measuring 224Ra and 223Ra by delayed-coincidence counting. Marine Chemistry, 109(3–4): 188–197

|

|

Moore W S, Arnold R. 1996. Measurement of 223Ra and 224Ra in coastal waters using a delayed coincidence counter. Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans, 101(C1): 1321–1329. doi: 10.1029/95JC03139

|

|

Moore W S, Reid D F. 1973. Extraction of radium from natural waters using manganese-impregnated acrylic fibers. Journal of Geophysical Research, 78(36): 8880–8886. doi: 10.1029/JC078i036p08880

|

|

Rama, Todd J F, Butts J L, et al. 1987. A new method for the rapid measurement of 224Ra in natural waters. Marine Chemistry, 22(1): 43–54. doi: 10.1016/0304-4203(87)90047-8

|

|

Sanial V, Kipp L E, Henderson P B, et al. 2018. Radium-228 as a tracer of dissolved trace element inputs from the Peruvian continental margin. Marine Chemistry, 201: 20–34. doi: 10.1016/j.marchem.2017.05.008

|

|

Sun Yin, Torgersen T. 1998. The effects of water content and Mn-fiber surface conditions on 224Ra measurement by 220Rn emanation. Marine Chemistry, 62(3–4): 299–306

|

|

Tan Ehui, Wang Guizhi, Moore W S, et al. 2018. Shelf-scale submarine groundwater discharge in the Northern South China Sea and East China Sea and its geochemical impacts. Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans, 123(4): 2997–3013. doi: 10.1029/2017JC013405

|

|

Trier R M, Broecker W S, Feely H W. 1972. Radium-228 profile at the second Geosecs intercalibration station, 1970, in the North Atlantic. Earth and Planetary Science Letters, 16(1): 141–145. doi: 10.1016/0012-821X(72)90249-X

|

|

Wang Guizhi, Han Aiqin, Chen Liwen, et al. 2018. Fluxes of dissolved organic carbon and nutrients via submarine groundwater discharge into subtropical Sansha Bay, China. Estuarine, Coastal and Shelf Science, 207: 269–282

|

|

Wang Guizhi, Jing Wenping, Wang Shuling, et al. 2014. Coastal acidification induced by tidal-driven submarine groundwater discharge in a coastal coral reef system. Environmental Science & Technology, 48(22): 13069–13075

|

|

Wang Guizhi, Wang Zhangyong, Zhai Weidong, et al. 2015. Net subterranean estuarine export fluxes of dissolved inorganic C, N, P, Si, and total alkalinity into the Jiulong River Estuary, China. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta, 149: 103–114. doi: 10.1016/j.gca.2014.11.001

|

|

Xie Yongzhen, Huang Yipu, Shi Wenyuan, et al. 1994. Simultaneous concentration and determination of 226Ra, 228Ra in natural waters. Journal of Xiamen University: Natural Science (in Chinese), 33(S1): 86–90

|

|

Zhang Yan, Santos I R, Li Hailong, et al. 2020. Submarine groundwater discharge drives coastal water quality and nutrient budgets at small and large scales. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta, 290: 201–215. doi: 10.1016/j.gca.2020.08.026

|

supporting information-Dai Guiyuan.docx

supporting information-Dai Guiyuan.docx

|

|