| Citation: | Chunqian Li, Meng Li, Guangquan Chen, Huaming Yu, Chenglun Zhang, Wen Liu, Jinjia Guo, Shibin Zhao, Lijun Song, Xiliang Cui, Ying Chai, Lu Cao, Diansheng Ji, Bochao Xu. In-situ detection equipment for radon-in-water: unattended operation and monthly investigations[J]. Acta Oceanologica Sinica, 2023, 42(8): 178-184. doi: 10.1007/s13131-023-2238-y |

Radon is an ideal geochemical tracer for the study of marine processes. Compared with traditional physical and chemical indicators such as temperature, salinity, dissolved oxygen, pH, etc., radon isotopes in the ocean are more robust to assess ocean processes on the time scale of 20 d due to their unique half-life. For example, it has been widely used as an ideal tool for studying processes such as submarine groundwater discharge (SGD) flux and material contribution, air-sea exchange flux, and water-rock interaction in coastal oceans ( Burnett and Dulaiova, 2003; Burnett et al., 2001, 2006; Dulaiova et al., 2005; Null et al., 2012; Prakash et al., 2018; Santos et al., 2010; Wang et al., 2019, 2020). High spatial-temporal resolution radon data are needed for an accurate long-term estimation of these processes, which might benefit the combination of radon and physical models for variation prediction (Xu et al.,2022).

In 2000, Burnett et al. (2001) demonstrated an automated system that can determine the radon activity in coastal ocean waters. The system was composed of a commercial radon-in-air analyzer RAD7 and a water-air exchanger. The RAD7 analyzed 222Rn from a constant stream of water passing through the air-water exchanger that distributes radon from the running flow of water to a closed air loop. In 2005, Dulaiova et al. (2005) demonstrated an automated multi-detector system in which the air stream was fed to three RAD7 connected in parallel. The system can measure radon concentration in water quickly and accurately. Note that RAD7 is designed to determine Rn by measuring α particles generated by the decay of radon’s daughters. However, the daughter of radon is a positively charged particle, which is particularly susceptible to the influence of humidity to be neutralized, resulting in a sharp decline in the measurement efficiency of RAD7. RAD7 needs to operate in an environment with relative humidity below 10% (Burnett et al., 2001; Xu et al., 2010), so additional desiccants are needed to remove moisture from the entire air loop. This leads to the need for someone on duty to change the drying unit regularly.

In recent years, radon measurement technology based on the pulsed ionization chamber (PIC) measurement principle has been applied to the measurement of radon concentration in water (Li et al., 2022; Seo and Kim, 2021; Zhao et al., 2022). The α particles generated by the decay of radon in the PIC will ionize the air, generating a large number of “electron-ion” pairs. The “electron-ion” pairs will drift towards the ionization chamber poles under the action of an electric field, resulting in a change in the electrical signal (Gavrilyuk et al., 2015; Studnička et al., 2019). Each α particle generates an electrical signal, so the radon concentration can be determined according to the number of electrical signals produced. Since it is measured as an electrical signal from the ionization of α particles, it is almost unaffected by humidity. More recently, Liu et al. (2022) reported that the measurement efficiency of the radon probe based on the pulse ionization principle is not significantly affected by relative humidity below 65%. Zhao et al. (2022) demonstrated a radon-measuring instrument based on the PIC measuring principle, which was composed of a PIC radon probe and a water gas separation device. The seawater was pumped into the water gas separation device by a water pump to achieve the separation of water and gas, and then the radon concentration in the gas phase was measured by the PIC radon probe. However, the gas extraction membrane module they used was not pressure resistant, which constrained the system functioning in shallow water settings.

In this work, we developed an in-situ measurement equipment (“PIC-radon”), which is based on gas-liquid separation through permeable sheet membrane and radon measurement through pulse ionization. The sheet membrane is pressure tolerant, so the system has the potential to be deployed into deep water. It has extremely low power consumption, minuscule size, and is barely influenced by humidity, making it particularly suitable for long-term in-situ observation, especially in harsh environments with limited human care or deployment spaces.

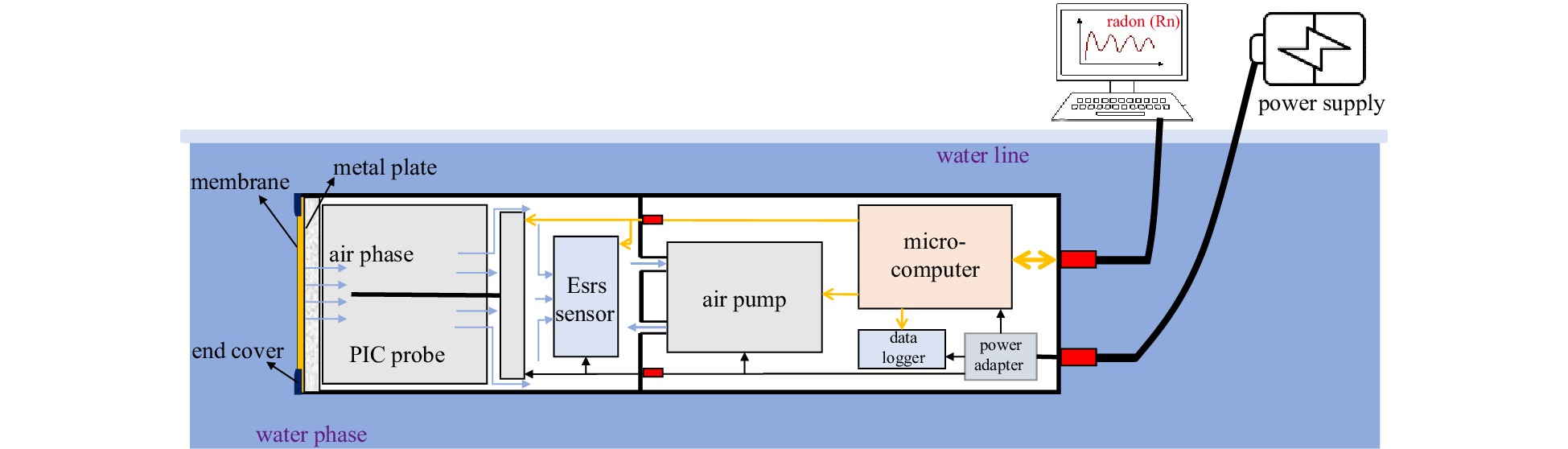

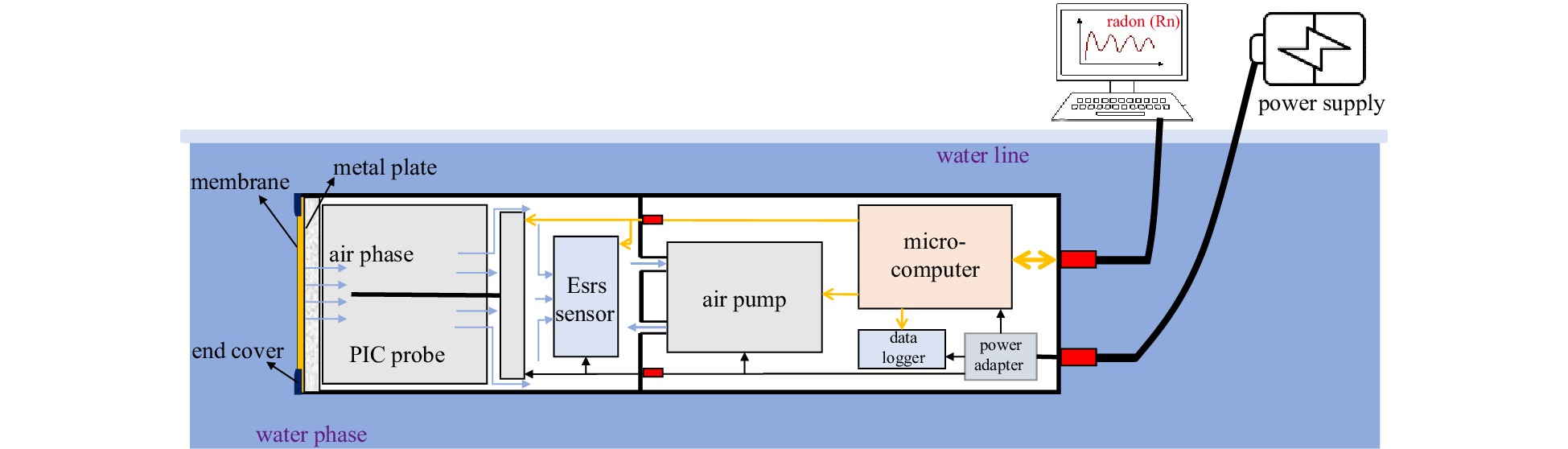

The entire “PIC-radon” device is functionally divided into the equilibration unit, measuring unit, and control unit. The equilibration unit mainly achieves gas-liquid separation, including permeable sheet membrane and sintered metal plate (Fig. 1). The measurement unit, mainly detects radon concentration and environmental parameters, including radon probe and air temperature-humidity-pressure sensor. The control unit mainly provides power to other modules, as well as functions such as data acquisition and storage. When the PIC-radon system is immersed in seawater, the dissolved radon gas in the seawater will be degassed by passing through the permeable membrane, which then enters the measurement unit and is counted by the radon probe in the measurement unit. At the same time, the environmental parameter sensor monitors the working state of the PIC chamber. The control unit accelerates the gas circulation in the PIC by controlling the diaphragm air pump and conducts periodic data acquisition and storage.

The permeation sheet membrane and the sintered metal plate of the equilibration unit are located at the end of the entire device and sealed through the end cover (Fig. 1). The permeable sheet membrane (Biogeneral, USA) is made of Teflon material, used for gas-liquid separation. The sintered metal plate serves as a supporting material under the permeable membrane. There are evenly distributed pore sizes on the metal plate to make sure radon gas enters the counting chamber effectively.

The measurement unit mainly consists of a PIC radon probe and environmental sensors (Fig. 2a). This PIC radon probe (Ekman Technology, China) is used to measure radon concentration in air, which sensitivity is (0.559 ± 0.012) cpm/(pCi·L−1) (cpm: counts per minute), the background is (0.10 ± 0.11) cpm and detection range is 3.0−10 000 Bq/m³. The volume of its ionization chamber is only 200 mL. We can also choose radon probes with larger detection volumes according to measurement requirements. We used a BME680 sensor (Bosch Company, Germany) to monitor air temperature, atmospheric pressure, and relative humidity inside the PIC chamber simultaneously. This sensor has a small size, low power consumption, and can meet a sampling rate of once per second, making it very suitable for monitoring air conditions. The measurement unit is powered and controlled by the control unit through two watertight cables (Fig. 1).

We developed a set of integrated circuits as the control unit of the instrument. It mainly consists of four parts: core processing module, data storage module, air circuit control module, and power management module (Fig. 2a). The core processing module (STMicroelectronics Inc., Italy) is used to control other modules and interact with the PC software. The data storage module (a TF card) is used to store relevant data, including time, radon concentration, cpm, relative humidity, atmospheric pressure, and air temperature. The air circuit control module is composed of a micro diaphragm pump (Kamoer Company, China) and some hoses, and its inlet and outlet are connected to the measurement unit. By turning on the micro diaphragm pump, the permeated gas can be distributed more quickly and evenly in the ionization chamber, which is conducive to achieving more accurate measurements. The power management module can convert the external power supply into the voltage required by the entire instrument, such as the 12 V of the radon probe and the 6 V of the micro diaphragm pump, etc.

The size of the equipment is 31 cm in length and 11 cm in diameter (Fig. 2b). In the air, the weight of the equipment is less than 5 kg. The overall power consumption of the equipment is less than 2.5 W and can be powered by battery or AC power via a two-core watertight cable. The data of the instrument is stored in the data storage module and/or uploaded to the PC software.

A PC software was developed which can achieve real-time control and data collection of the PIC-radon (Fig. 3). Real-time interactive communication between PIC-radon and PC software is based on the RS-232 Modbus protocols with the baud of 19 200 bps (bits per second), which is accomplished through a four-core watertight cable. The sampling interval can be set up as 10 min or any other manually set-up interval. After the period is set, the real-time measurement data will be periodically uploaded to the PC software. The collected data are stored as text files in the computer and displayed as diagrams in the PC software (Fig. 3). If the PIC-radon is found to be working abnormally, one can use this software to reset the measurement. It is also easy to turn on/off the diaphragm air pump and set the duration through the PC software.

To assess the detection efficiency of the PIC-radon, we conducted an indoor-tank laboratory experiment to compare the PIC-radon with the commercial RAD AQUA-RAD7 system (Fig. 4).

At the beginning of the experiment, the PIC-radon system and the RAD7 were both placed in the air with the internal air pump on until they reached equilibrium in the air. To meet RAD7’s measurement requirements, a drying column was connected in series throughout the gas path to reduce the relative humidity. Then the PIC-radon system and RAD AQUA-RAD7 were both set up in the tank, which was filled with high-radon tap water. We used a submersible pump to provide a continuous water flow to the water-air exchanger. For quick balancing, the water flow speed was set to 2 L/min (Schmidt et al., 2008; Zhao et al., 2022). In the previous calibration, the measurement efficiency of the RAD7 was known to be (0.015±0.000 3) cpm/(Bq·m−3). The PIC-radon system and RAD AQUA-RAD7 measured the activity of radon continuously for 2 h with 10 min data reporting interval. Through this experiment, we can evaluate the degassing efficiency and equilibrium time of the PIC-radon system.

To test the PIC-radon in seawater, a long-term in-situ observation of the offshore area was conducted from July 20, 2022 at the Jiaozhou Bay, China (Fig. 5). We still use the PIC-radon and the RAD AQUA-RAD7 system for comparison tests. To ensure the accuracy of the measurement, the PIC-radon and the submersible pump for the RAD AQUA-RAD7 were fixed on the same floating platform, and approximately 1.5 m away from the water surface. Just like before, the water flow speed was set to 2 L/min. The entire comparison test lasted for about 70 h and the data collection interval for both systems was set to 10 min. Afterward, we used the PIC-radon to carry out long-term in-situ observation from July 20 to August 2, 2022 in the Jiaozhou Bay to assess the effect of tides on radon concentrations.

To test the PIC-radon in groundwater, we conducted a long-term in-situ observation in a groundwater well at the Laizhou Bay coast, China (Fig. 6). The PIC-radon was placed at 1.5 m water depth in the brine well (length: 40 cm, width: 30 cm). The distance between the ground and the surface of the well water is about 15 m. Firstly, we measured the long-term standing groundwater from November 3 to November 22, 2022. Then we pumped out the old groundwater and started measuring the newly replenished groundwater from January 4 to January 17, 2023. As we observed daily trends, we set the sampling interval to 30 min, and radon activities were characterized using a 1-h interval averaging approach to smooth out the statistical scatters.

In the air, the PIC-radon system background value ranged from 0.3 cpm to 1.1 cpm within 100 min counting, with an average of (0.67 ± 0.27) cpm (n = 10, n: the number of counting results). This value is basically consistent with the previous laboratory test results.

In the tank, the RAD AQUA-RAD7 system reached the water-gas equilibration after about 30 min, while the PIC-radon system needs about 230 min. When both systems reached water-gas equilibration, the average value of RAD7 and PIC-radon by averaging the count rates of the platform period is (7.83 ± 1.13) cpm (n = 12) and (2.17 ± 0.41) cpm (n = 12), respectively. The measurement efficiency of PIC-radon is about 28% of that of the RAD AQUA-RAD7 system. Because of the lower degassing efficiency of sheet membrane compared with the water-gas exchanger, based on statistical analysis, we found a lower measurement efficiency and longer water-gas equilibration time of the PIC-radon compared with those of RAD AQUA-RAD7 system. However, the data variation trends of both systems were consistent with each other (Fig. 7).

According to previous laboratory tank experiments, the measurement efficiency of PIC-radon is about 28% of that of the RAD AQUA-RAD7 system, which can be used as efficiency to calculate the radon activities of PIC-radon. Meanwhile, as the equilibrium time of PIC-radon is about 3.5 h longer than that of RAD AQUA-RAD7 based on the previous laboratory tank experiments, we shifted the overall data of PIC-radon forward by 3.5 h as shown in Fig. 8.

As shown in Fig. 8a, the radon activities in the nearshore area of the Jiaozhou Bay ranged from 124 Bq/m3 to 356 Bq/m3 as determined by the PIC-radon, and ranged from 93 Bq/m3 to 473 Bq/m3 as determined by RAD AQUA-RAD7 system; the average radon activities are (241 ± 50) Bq/m3 and (228 ± 94) Bq/m3, respectively. The average values of both systems are basically the same. The long-term monitoring data indicate that the variation of radon activities are inversely correlated with the local tides, with radon peaks generally at low tide (Fig. 8a). The PIC-radon system is not as sensitive as the RAD AQUA-RAD7 system. This is because the equilibrium time of the permeation membrane is longer, resulting in tidal variations being smoothed. Therefore, the PIC-radon system is especially functional in scenarios with the demand for long-term variations with daily scale resolution.

As shown in Fig. 8b, we found the concentration was significantly affected by the astronomical tide. At astronomical neap tides, radon concentration values ranged from 200 Bq/m3 to 400 Bq/m3. With the arrival of astronomical spring tides, the radon concentration value significantly increases. The highest concentration (875 Bq/m3) of radon occurs at the lowest astronomical tide (July 30), which is about 4 times the lowest value. After the spring tide, the radon concentration rapidly decreased again.

In the first section, when the PIC-radon was placed in the brine well, the radon activities rose to around 1 500 Bq/m³ after about 10 h (Fig. 9). The water-gas equilibration time is longer than that of laboratory tank experiments. Perhaps because the water in the well was stationary, the efficiency of water-gas exchange through the permeable sheet membrane was reduced. Afterward, the radon activity continued to rise and reached its peak. Finally, the radon concentration has been fluctuating around 2 000 Bq/m³. In the second section, with the replenishment of fresh groundwater, the concentration of radon rose rapidly and reached a maximum of 8 229 Bq/m³ (Fig. 9). This result indicated that the instrument had a very good and fast response to concentration changes. Through these two measurements, we could see that the difference in radon concentration between old groundwater and new groundwater was very obvious. Afterward, the radon concentration began to decrease, but the rate of decline was significantly slower than the radioactive decay curve, indicating that there must be continuous groundwater exchange during this period.

It should be noted that the instrument remained in the well after the first stage of experiments and was not removed until the second stage of experiments completed. The whole process lasted 75 d. When we took out the instrument from the well, we found that some sediment covered the surface of the permeation sheet membrane. We only need a simple rinse of the instrument. This result indicated that the instrument can be well used for long-term in-situ observation.

We have developed a new instrument that can be used for long-term in-situ observation of radon concentration in water. It has the advantages of low power consumption, minuscule size, barely influenced by humidity, and so on. However, it also has the disadvantages of low degassing efficiency and long water-gas equilibrium time. The equilibrium time is about 4 h, and the measurement efficiency is about 28% of the RAD AQUA-RAD7 system. Therefore, it is very suitable for long-term in-situ observation in a high-concentration environment, especially in a harsh environment with limited human care and deployment space. The PIC-radon system is especially functional in scenarios with the demand for long-term variations with daily scale resolution. For example, it is used for long-term monitoring of groundwater at the land-sea boundary to assess the issues of seawater intrusion and soil salinization. Meanwhile, it can also be deployed on other unmanned mobile platforms, such as unmanned boats or drifting buoys. The next step will be to further improve the degassing efficiency and equilibrium time of the device by selecting different permeable membrane materials. Research in submarine groundwater discharge and ocean-atmosphere gas exchange will benefit from utilizing this system.

|

Burnett W C, Aggarwal P K, Aureli A, et al. 2006. Quantifying submarine groundwater discharge in the coastal zone via multiple methods. Science of the Total Environment, 367(2−3): 498–543. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2006.05.009

|

|

Burnett W C, Dulaiova H. 2003. Estimating the dynamics of groundwater input into the coastal zone via continuous radon-222 measurements. Journal of Environmental Radioactivity, 69(1−2): 21–35. doi: 10.1016/S0265-931X(03)00084-5

|

|

Burnett W C, Kim G, Lane-Smith D. 2001. A continuous monitor for assessment of 222Rn in the coastal ocean. Journal of Radioanalytical and Nuclear Chemistry, 249(1): 167–172. doi: 10.1023/A:1013217821419

|

|

Dulaiova H, Peterson R, Burnett W C, et al. 2005. A multi-detector continuous monitor for assessment of 222Rn in the coastal ocean. Journal of Radioanalytical and Nuclear Chemistry, 263(2): 361–363. doi: 10.1007/s10967-005-0063-8

|

|

Gavrilyuk Y M, Gangapshev A M, Gezhaev A M, et al. 2015. High-resolution ion pulse ionization chamber with air filling for the 222Rn decays detection. Nuclear Instruments and Methods in Physics Research Section A: Accelerators, Spectrometers, Detectors and Associated Equipment, 801: 27–33

|

|

Li Chunqian, Zhao Shibin, Zhang Chenglun, et al. 2022. Further refinements of a continuous radon monitor for surface ocean water measurements. Frontiers in Marine Science, 9: 1047126. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2022.1047126

|

|

Liu Wen, Li Chunqian, Cai Pinghe, et al. 2022. Quantifying 224Ra/228Th disequilibrium in sediments via a pulsed ionization chamber (PIC). Marine Chemistry, 245: 104160. doi: 10.1016/j.marchem.2022.104160

|

|

Null K A, Dimova N T, Knee K L, et al. 2012. Submarine groundwater discharge-derived nutrient loads to San Francisco Bay: implications to future ecosystem changes. Estuaries and Coasts, 35(5): 1299–1315. doi: 10.1007/s12237-012-9526-7

|

|

Prakash R, Srinivasamoorthy K, Gopinath S, et al. 2018. Radon isotope assessment of submarine groundwater discharge (SGD) in Coleroon River Estuary, Tamil Nadu, India. Journal of Radioanalytical and Nuclear Chemistry, 317(1): 25–36. doi: 10.1007/s10967-018-5877-2

|

|

Santos I R, Peterson R N, Eyre B D, et al. 2010. Significant lateral inputs of fresh groundwater into a stratified tropical estuary: evidence from radon and radium isotopes. Marine Chemistry, 121(1–4): 37–48. doi: 10.1016/j.marchem.2010.03.003

|

|

Schmidt A, Schlueter M, Melles M, et al. 2008. Continuous and discrete on-site detection of radon-222 in ground- and surface waters by means of an extraction module. Applied Radiation and Isotopes, 66(12): 1939–1944. doi: 10.1016/j.apradiso.2008.05.005

|

|

Seo J, Kim G. 2021. Rapid and precise measurements of radon in water using a pulsed ionization chamber. Limnology and Oceanography: Methods, 19(4): 245–252. doi: 10.1002/lom3.10419

|

|

Studnička F, Štěpán J, Šlégr J. 2019. Low-cost radon detector with low-voltage air-ionization chamber. Sensors, 19(17): 3721. doi: 10.3390/s19173721

|

|

Wang Xuejing, Li Hailong, Zhang Yan, et al. 2019. Submarine groundwater discharge revealed by 222Rn: comparison of two continuous on-site 222Rn-in-water measurement methods. Hydrogeology Journal, 27(5): 1879–1887. doi: 10.1007/s10040-019-01988-z

|

|

Wang Qianqian, Li Hailong, Zhang Yan, et al. 2020. Submarine groundwater discharge and its implication for nutrient budgets in the western Bohai Bay, China. Journal of Environmental Radioactivity, 212: 106132. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvrad.2019.106132

|

|

Xu Bochao, Burnett W C, Lane-Smith D, et al. 2010. A simple laboratory-based radon calibration system. Journal of Radioanalytical and Nuclear Chemistry, 283(2): 457–463. doi: 10.1007/s10967-009-0427-6

|

|

Xu Bochao, Li Sanzhong, Burnett W C, et al. 2022. Radium-226 in the global ocean as a tracer of thermohaline circulation: synthesizing half a century of observations. Earth-Science Reviews, 226: 103956. doi: 10.1016/j.earscirev.2022.103956

|

|

Zhao Shibin, Li Meng, Burnett W C, et al. 2022. In-situ radon-in-water detection for high resolution submarine groundwater discharge assessment. Frontiers in Marine Science, 9: 1001554. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2022.1001554

|

| 1. | XiangLong Dong, Ziji Ma, Weicheng Ding, et al. Continuous monitoring experiment of soil radon levels using a semiconductor-based measuring instrument. Nuclear Instruments and Methods in Physics Research Section A: Accelerators, Spectrometers, Detectors and Associated Equipment, 2024, 1069: 169885. doi:10.1016/j.nima.2024.169885 |