Environmental effects of mariculture in China: An overall study of nitrogen and phosphorus loads

-

Abstract: Eutrophication in coastal area has become more and more serious and mariculture potential is a main cause. Although there are some quantitative research on nutrient loads in national and global perspective, the calculation method problems make the results controversial. In this paper, the farming activities are divided into fed culture types (include cage culture and pond culture) and extractive culture types (e.g. seaweed, filter-feeding shellfish culture). Based on the annual yield of China in 2019 and feed coefficient of fed culture types and carbon (C), nitrogen (N), and phosphorus (P) content of extractive culture types, the annual nutrient loads was estimated. The results showed that to coastal region of China (1) annual nutrient released by fed culture types were about 58 451 t of N, 9 081 t of P, and annual nutrient removed by harvest of extractive culture types were 109 245 t of N, 11 980 t of P and 1.86×106 t of C. Overall, the net amount of nutrient removed annually by mariculture industry were 50 794 t of N and 2 901 t of P. (2) The nutrient released from mariculture industry influenced nutrient stoichiometry. Pond farming and seaweed farming had the potential of increasing the molar concentration ratio of N and P (N:P), while cage farming and bivalve farming decreased the N:P. (3) Due to different mariculture types and layouts in the coastal regions in China, N and P loading were regional different. Among the coastal regions in China, net release of nutrient from mariculture occurred only in Hainan and Guangxi regions, while in the other regions, N and P were completely removed by harvest. We suggest decrease the amount of fed culture types and increase the amount of integrated culture with extractive culture types. This study will help to adjust mariculture structure and layout at the national level to reduce the environmental impact.

-

Key words:

- fed culture type /

- extractive culture type /

- nutrient loads /

- nitrogen /

- phosphorus

-

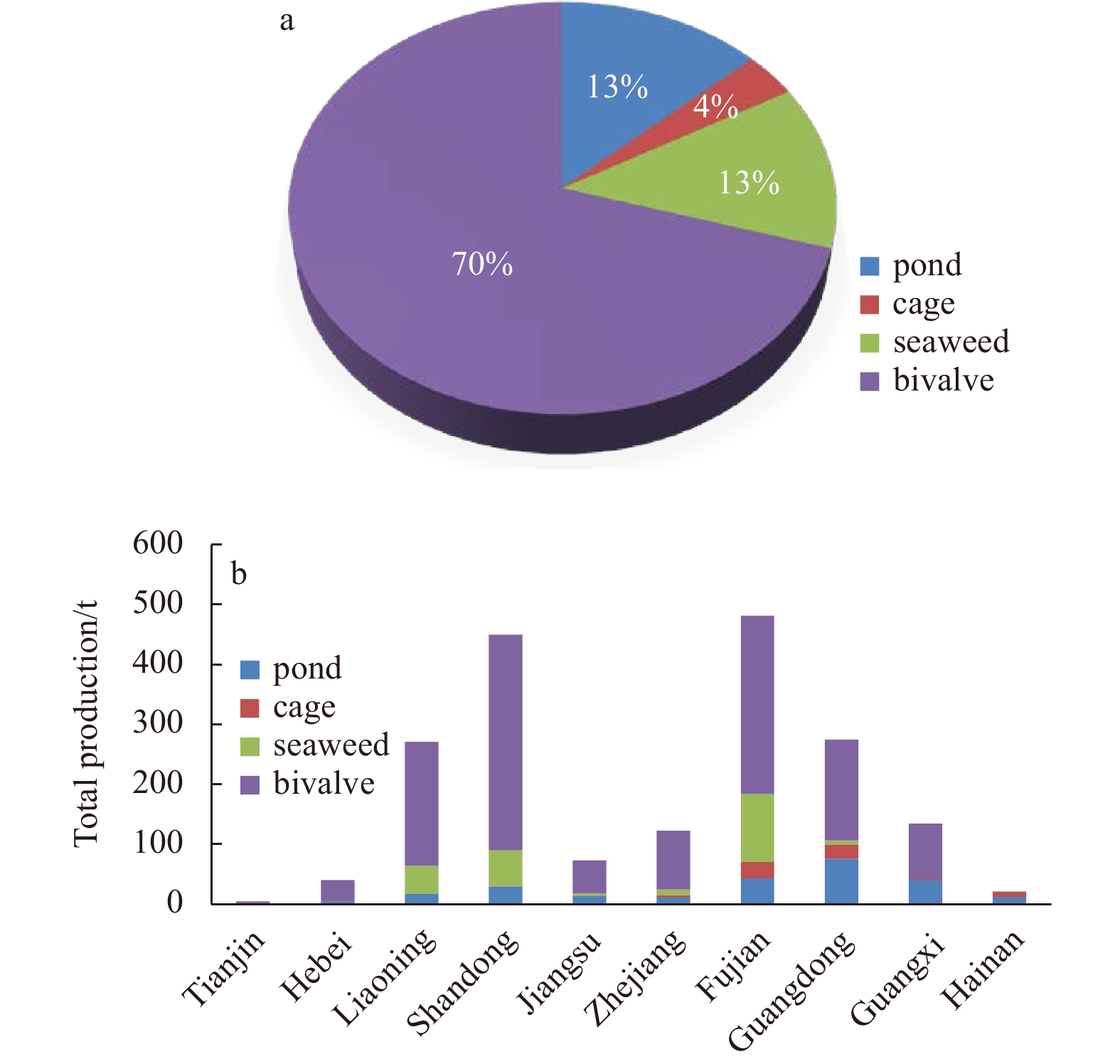

Figure 1. Percentage of total production in typical mariculture systems (a), and the proportion of yield in typical mariculture systems in coastal provinces of China in 2019 (b) (Zhang et al., 2020a).

Table 1. The waste coefficient of pollutant discharge coefficient, yield and nutrient release from the main species of the pond mariculture in China in 2019

Waste sources Yield/(103 t) Waste coefficient/ (g·kg−1) N release/ (103 t) P release/ (103 t) N P Takifugu sp. 17.473 15.51 0.65 0.28 0.02 Sea bass 180.267 11.85 0.86 1.36 0.07 Penaeus vannamei 1 144.370 1.82 0.29 3.14 0.39 Penaeus monodon 84.066 2.04 0.32 0.25 0.03 Penaeus chinensis 38.583 1.41 0.25 0.05 0.01 Penaeus japonicus 50.968 1.67 0.31 0.07 0.01 Portunus sp. 113.810 2.22 0.96 0.27 0.12 Scylla sp. 160.616 2.65 0.11 0.45 0.02 Sea cucumber 171.700 4.37 0.1 0.43 0.01 Sea urchin 8.243 4.98 0.12 0.04 0.00 Jellyfish 89.576 3.31 0.36 0.29 0.03 Others 421.400 8.78 0.75 3.70 0.32 Total 2481.027 − − 10.33 1.03 Note: − represents no data. Table 2. The waste coefficient of pollutant producing coefficient, yield and nutrient release from the main species of the cage mariculture of China in 2019

Species Yield

/(103 t)Waste coefficient/(g·kg−1) N release/ (103 t) P release/(103 t) N P Pseudosciaena crocea 225.55 72.02 12.07 16.24 2.72 Rachycentron canadum 42.22 76.47 12.77 3.23 0.54 Seriola sp. 30.00 76.47 12.77 2.29 0.38 Seabream 101.28 72.02 12.07 7.29 1.22 Sciaenops ocellatus 70.19 72.02 12.07 5.06 0.85 Epinephelus sp. 183.13 76.47 12.77 14.00 2.34 Total 652.37 − − 48.11 8.05 Note: − represents no data. Table 3. The contents of N, P and C, and N, P, C removed by harvest of the main species of seaweed of China in 2019

Species Yield/ t N content/% P content/% C content/% N remove/t P remove/t C remove/ (103 t) Kelp 1 461 058 1.63 0.379 31.20 23 815.25 5 537.41 506.69 Undaria 152 572 3.41 0.33 28.81 2 486.92 578.25 62.13 Laver 135 252 1.88 0.055 41.96 4 612.09 446.33 58.15 Gracilaria 293 179 1.63 0.379 24.50 5 511.77 161.25 98.86 Others 24 476 2.31 0.25 30.27 565.40 61.19 10.94 Total 2 066 537 − − − 36 991.43 6 784.43 736.77 Note: − represents no data. Table 4. The contents of N, P and C contents, and N, P, C removed by harvest of the main species of bivalves of China in 2019

Item Oyster Scallop Mussel Clam Others Total/(103 t) W/(106 t) 4.83 1.86 0.88 4.17 1.21 − r 0.65 0.64 0.75 0.53 0.64 − t 0.02 0.11 0.06 0.14 0.04 − N Cbivalve-m/% 9.23 10.51 9.23 9.00 9.92 − P Cbivalve-m/% 0.10 0.10 0.10 0.54 0.21 − C Cbivalve-m/% 0.45 0.44 0.46 0.42 0.44 − N Cbivalve-s/% − − 0.14 − − − P Cbivalve-s/% − − 0.03 − − − C Cbivalve-s/% − − 0.11 − − − N remove/(103 t) 10.73 15.70 4.62 31.11 4.31 65.88 P remove/(103 t) 9.87 4.52 2.27 21.68 2.85 4.12 C remove/(103 t) 383.37 180.01 98.29 349.09 102.26 1 112.79 Note: − represents no data. W is the annual production; Cbivalve-m and Cbivalve-s are N or P contents in dry tissue and shell, respectively. Table 5. The N and P loads and molar concentration ratios of N and P (N:P) from four typical mariculture systems and C sink from extractive mariculture system of China in 2019

Item Bivalve Seaweed Pond Cage Total Yield/(106 t) 13.16 2.41 2.48 0.65 18.71 N load/t −65 057 −44 188 10 330 48 121 −50 794 P load/t −4 097 −7 883 1 026 8 053 −2 901 N:P 35:1 12:1 22:1 13:1 39:1 C sink/t 1 127 735 736 770 − − 1 864 505 Note: − represents no data. -

[1] Aguilar-Manjarrez J, Soto D, Brummett R. 2017. Aquaculture zoning, site selection and area management under the ecosystem approach to aquaculture. A handbook. Rome: FAO, and World Bank Group, 62–395 [2] Bambaranda B V A S M, Tsusaka T W, Chirapart A, et al. 2019. Capacity of Caulerpa lentillifera in the removal of fish culture effluent in a recirculating aquaculture system. Processes, 7(7): 440. doi: 10.3390/pr7070440 [3] Bannister R J, Johnsen I A, Hansen P K, et al. 2016. Near- and far-field dispersal modelling of organic waste from Atlantic salmon aquaculture in fjord systems. ICES Journal of Marine Science, 73(9): 2408–2419. doi: 10.1093/icesjms/fsw027 [4] Bouwman A F, Beusen A H W, Overbeek C C, et al. 2013. Hindcasts and future projections of global inland and coastal nitrogen and phosphorus loads due to finfish aquaculture. Reviews in Fisheries Science, 21(2): 112–156. doi: 10.1080/10641262.2013.790340 [5] Boyd C E. 2003. Guidelines for aquaculture effluent management at the farm-level. Aquaculture, 226(1–4): 101–112. doi: 10.1016/S0044-8486(03)00471-X [6] Brigolin D, Dal Maschio G, Rampazzo F, et al. 2009. An individual-based population dynamic model for estimating biomass yield and nutrient fluxes through an off-shore mussel (Mytilus galloprovincialis) farm. Estuarine, Coastal and Shelf Science, 82(3): 365–376, [7] Cai Huiwen, Sun Yinglan. 2007. Management of marine cage aquaculture environmental carrying capacity method based on dry feed conversion rate. Environment Pollution Research, 14(7): 463–469 [8] Cao Ling, Wang Weimin, Yang Yi, et al. 2007. Environmental impact of aquaculture and countermeasures to aquaculture pollution in China. Environmental Science and Pollution Research-International, 14(7): 452–462. doi: 10.1065/espr2007.05.426 [9] Carballeira C, Cebro A, Villares R, et al. 2018. Assessing changes in the toxicity of effluents from intensive marine fish farms over time by using a battery of bioassays. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 25(13): 12739–12748. doi: 10.1007/s11356-018-1403-x [10] Chen Chao, Lou Yongjiang, Chen Xiaofang. 2013. Study on technology of freshness-keeping of Porphyra haitanensis. Science and Technology of Food Industry, 34(13): 309–312. doi: 10.13386/j.issn1002-0306.2013.13.070 [11] Chen Yibo, Song Guobao, Zhao Wenxing, et al. 2016. Estimating pollutant loadings from mariculture in China. Marine Environmental Science, 35(1): 1–6,12. doi: 10.13634/j.cnki.mes.2016.01.001 [12] Christensen P B, Glud R N, Dalsgaard T, et al. 2003. Impacts of longline mussel farming on oxygen and nitrogen dynamics and biological communities of coastal sediments. Aquaculture, 218(1-4): 567–588. doi: 10.1016/S0044-8486(02)00587-2 [13] Dame R F. 1996. Ecology of Marine Bivalves: An Ecosystem Approach. Boca Raton: CRC Press, 1–272. doi: 10.1201/9781003040880 [14] Dempster T, Sanchez-Jerez P, Fernandez-Jover D, et al. 2011. Proxy measures of fitness suggest coastal fish farms can act as population sources and not ecological traps for wild gadoid fish. PLoS ONE, 6(1): e15646. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0015646 [15] Dumbauld B R, Ruesink J L, Rumrill S S. 2009. The ecological role of bivalve shellfish aquaculture in the estuarine environment: A review with application to oyster and clam culture in West Coast (USA) estuaries. Aquaculture, 290: 196–233 [16] FAO. 2020. The state of world fisheries and aquaculture 2020. Sustainability in action. Rome: FAO, 37–128 [17] Farmaki E G, Thomaidis N S, Pasias I N, et al. 2014. Environmental impact of intensive aquaculture: investigation on the accumulation of metals and nutrients in marine sediments of Greece. Science of the Total Environment, 485–486: 554–562, [18] Ferreira J G, Saurel C, Silva J D L E, et al. 2014. Modelling of interactions between inshore and offshore aquaculture. Aquaculture, 426–427: 154–164, [19] Filgueira R, Guyondet T, Reid G K, et al. 2017. Vertical particle fluxes dominate integrated multi-trophic aquaculture (IMTA) sites: implications for shellfish-finfish synergy. Aquaculture Environment Interactions, 9: 127–143. doi: 10.3354/aei00218 [20] Gallardi D. 2014. Effects of bivalve aquaculture on the environment and their possible mitigation: a review. Fisheries and Aquaculture Journal, 5(3): 1000105. doi: 10.4172/2150-3508.1000105 [21] Grant J, Hatcher A, Scott D B, et al. 1995. A multidisciplinary approach to evaluating impacts of shellfish aquaculture on benthic communities. Estuaries, 18(1): 124–144. doi: 10.2307/1352288 [22] Holmer M. 2010. Environmental issues of fish farming in offshore waters: perspectives, concerns and research needs. Aquaculture Environment Interactions, 1(1): 57–70. doi: 10.3354/aei00007 [23] Islam M S. 2005. Nitrogen and phosphorus budget in coastal and marine cage aquaculture and impacts of effluent loading on ecosystem: review and analysis towards model development. Marine Pollution Bulletin, 50(1): 48–61. doi: 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2004.08.008 [24] Joesting H M, Blaylock R, Biber P, et al. 2016. The use of marine aquaculture solid waste for nursery production of the salt marsh plants Spartina alterniflora and Juncus roemerianus. Aquaculture Reports, 3: 108–114. doi: 10.1016/j.aqrep.2016.01.004 [25] Liu Chunxiang, Zou Dinghui, Liu Zhiwei, et al. 2020. Ocean warming alters the responses to eutrophication in a commercially farmed seaweed, Gracilariopsis lemaneiformis. Hydrobiologia, 847(3): 879–893. doi: 10.1007/s10750-019-04148-2 [26] Meier H E M, Eilola K, Almroth-Rosell E, et al. 2019. Correction to: disentangling the impact of nutrient load and climate changes on Baltic Sea hypoxia and eutrophication since 1850. Climate Dynamics, 53(1−2): 1167–1169. doi: 10.1007/s00382-018-4483-x [27] National Pollution Source Census. 2009. The first National Pollution Source Census: Manual of Producing and Blowdown Coefficient of Aquaculture Pollutants (in Chinese). Beijing: The Calculation Project Team of Producing and Blowdown Coefficient of Aquaculture Pollutants for the First National Pollution Source Census, 1–100 [28] Newell R I E. 2004. Ecosystem influences of natural and cultivated populations of suspension-feeding bivalve molluscs: a review. Journal of Shellfish Research, 23(1): 51–61 [29] Nichols C R, Zinnert J, Young D R. 2019. Degradation of coastal ecosystems: causes, impacts and mitigation efforts. In: Wright L D, Nichols C R, eds. Tomorrow’s Coasts: Complex and Impermanent. Cham: Springer, 119–136. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-75453-6_8 [30] Nixon S W, Ammerman J W, Atkinson L P, et al. 1996. The fate of nitrogen and phosphorus at the land-sea margin of the North Atlantic Ocean. Biogeochemistry, 35(1): 141–180. doi: 10.1007/BF02179826 [31] Oh E S, Edgar G J, Kirkpatrick J B, et al. 2015. Broad-scale impacts of salmon farms on temperate macroalgal assemblages on rocky reefs. Marine Pollution Bulletin, 98(1–2): 201–209. doi: 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2015.06.049 [32] Petersen J K, Saurel C, Nielsen P, et al. 2016. The use of shellfish for eutrophication control. Aquaculture International, 24(3): 857−878 [33] Price C, Black K D, Hargrave B T, et al. 2015. Marine cage culture and the environment: effects on water quality and primary production. Aquaculture Environment Interactions, 6(2): 151–174. doi: 10.3354/aei00122 [34] Richard M, Archambault P, Thouzeau G, et al. 2007. Influence of suspended scallop cages and mussel lines on pelagic and benthic biogeochemical fluxes in Havre-aux-Maisons Lagoon, Îles-de-la-Madeleine (Quebec, Canada). Canadian Journal of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences, 64(11): 1491–1505. doi: 10.1139/f07-116 [35] Sarà G, Lo Martire M, Sanfilippo M, et al. 2011. Impacts of marine aquaculture at large spatial scales: evidences from N and P catchment loading and phytoplankton biomass. Marine Environmental Research, 71(5): 317–324. doi: 10.1016/j.marenvres.2011.02.007 [36] Shen Gongming, Huang Ying, Mu Xiyan, et al. 2018. Aquaculture pollution discharge measurement and status analysis based on statistical yield. Chinese Agricultural Science Bulletin, 34(2): 123–129 [37] Sun Ke, Zhang Jihong, Lin Fan, et al. 2021. Evaluating the growth potential of a typical bivalve-seaweed integrated mariculture system—a numerical study of Sungo Bay, China. Aquaculture, 532: 736037. doi: 10.1016/j.aquaculture.2020.736037 [38] Tang Qisheng, Han Dong, Mao Yuze, et al. 2016. Species composition, non-fed rate and trophic level of Chinese aquaculture. Journal of Fishery Sciences of China, 23(4): 729–758. doi: 10.3724/SP.J.1118.2016.16113 [39] Tang Qisheng, Zhang Jihong, Fang Jianguang. 2011. Shellfish and seaweed mariculture increase atmospheric CO2 absorption by coastal ecosystems. Marine Ecology Progress Series, 424: 97–104. doi: 10.3354/meps08979 [40] Wang Junjie, Beusen A H W, Liu Xiaochen, et al. 2020. Aquaculture production is a large, spatially concentrated source of nutrients in Chinese freshwater and coastal seas. Environmental Science & Technology, 54(3): 1464–1474. doi: 10.1021/acs.est.9b03340 [41] Wang Xinxin, Olsen L M, Reitan K I, et al. 2012. Discharge of nutrient wastes from salmon farms: environmental effects, and potential for integrated multi-trophic aquaculture. Aquaculture Environment Interactions, 2(3): 267–283. doi: 10.3354/aei00044 [42] Wu R S S. 1995. The environmental impact of marine fish culture: Towards a sustainable future. Marine Pollution Bulletin, 31(4−12): 159–166. doi: 10.1016/0025-326X(95)00100-2 [43] Xiao Xi, Agusti S, Lin Fang, et al. 2017. Nutrient removal from Chinese coastal waters by large-scale seaweed aquaculture. Scientific Reports, 7(1): 46613. doi: 10.1038/srep46613 [44] Yang Yufeng, Fei Xiugeng. 2003. Prospects for bioremediation of cultivation of large-sized seaweed in eutrophic mariculture areas. Journal of Ocean University of Qingdao, 33(1): 53–57 [45] Yang Ping, Lai D Y F, Jin Baoshi, et al. 2017. Dynamics of dissolved nutrients in the aquaculture shrimp ponds of the Min River estuary, China: Concentrations, fluxes and environmental loads. Science of the Total Environment, 603–604: 256–267, [46] Zhang Ying, Bleeker A, Liu Junguo. 2015. Nutrient discharge from China’s aquaculture industry and associated environmental impacts. Environmental Research Letters, 10(4): 045002. doi: 10.1088/1748-9326/10/4/045002 [47] Zhang Xianliang, Cui Lifeng, Li Shumin, et al. 2020a. China Fishery Statistical Yearbook (in Chinese). Beijing: China Agriculture Press, 15−38 [48] Zhang Jihong, Hansen P K, Wu Wenguang, et al. 2020b. Sediment-focused environmental impact of long-term large-scale marine bivalve and seaweed farming in Sungo Bay, China. Aquaculture, 528: 735561. doi: 10.1016/j.aquaculture.2020.735561 [49] Zhang Yuzhen, Hong Huasheng, Chen Nengwang, et al. 2003. Discussion on estimating nitrogen and phosphorus pollution loads in aquaculture. Jourmal of Xiamen University: Natural Science (in Chinese), 42(2): 223−248 -

下载:

下载: