A new species of the glass sponge genus Walteria (Hexactinellida: Lyssacinosida: Euplectellidae) from northwestern Pacific seamounts, providing a biogenic microhabitat in the deep sea

-

Abstract: We report on a hexactinellid sponge new to science, Walteria demeterae sp. nov. , which was collected from the northwestern Pacific seamounts at depths of 1 271–1 703 m. Its tubular and basiphytous body, extensive lateral processes, numerous oval lateral oscula which are irregularly situated in the body wall, the presence of microscleres with oxyoidal, discoidal and onychoidal outer ends, and the absence of anchorate discohexasters, indicate it belongs to the genus Walteria of family Euplectellidae, which is also supported by molecular phylogenetic evidence from 18S, 28S, 16S rRNA and cytochrome c oxidase subunit I (COI) gene sequences. The unique morphotype, which is structured by a thin and rigid framework of body wall and lateral processes consisting of diactins, characterizes it as a new species. Local aggregations of individuals of this new species coupled with their associated macrofauna in the Suda Seamount are reported, highlighting its functional significance in providing biogenic microhabitats in the deep sea.

-

Key words:

- Euplectellidae /

- Walteria /

- integrative taxonomy /

- northwestern Pacific Ocean /

- Porifera /

- sponge aggregations

-

Figure 1. Walteria demeterae sp. nov. specimens. Holotype: in situ images (a1), whole collected specimen including five segments (a2), close-up images of a slightly damaged apex (a3), middle body (a4), and basal part (a5); paratype: in situ image (b1), whole collected specimen including two segments (b2), and close-up image of middle body showing fused skeleton (b3).

Figure 2. Walteria demeterae sp. nov., seafloor images of the same morphotype observed at dive ROV08 of cruise DY48/I from the Suda Seamount in the northwestern Pacific Ocean. a. Living individuals showing different shapes of tubular body with close-up images of small terminal osculum in the pointed apex, circular strands in the inner wall, and lateral processes projecting from the body wall; b. dead individuals showing different degrees of erosion with close-up images of pointed apex and basal part; c. concurrence of both living and dead individuals in one image; d. examples of invertebrates associated with living or dead individuals, including Comatulida, Spongicolidae, Ophioplinthaca defensor, Paguridae, Cirripedia and others (from top to bottom, then from left to right).

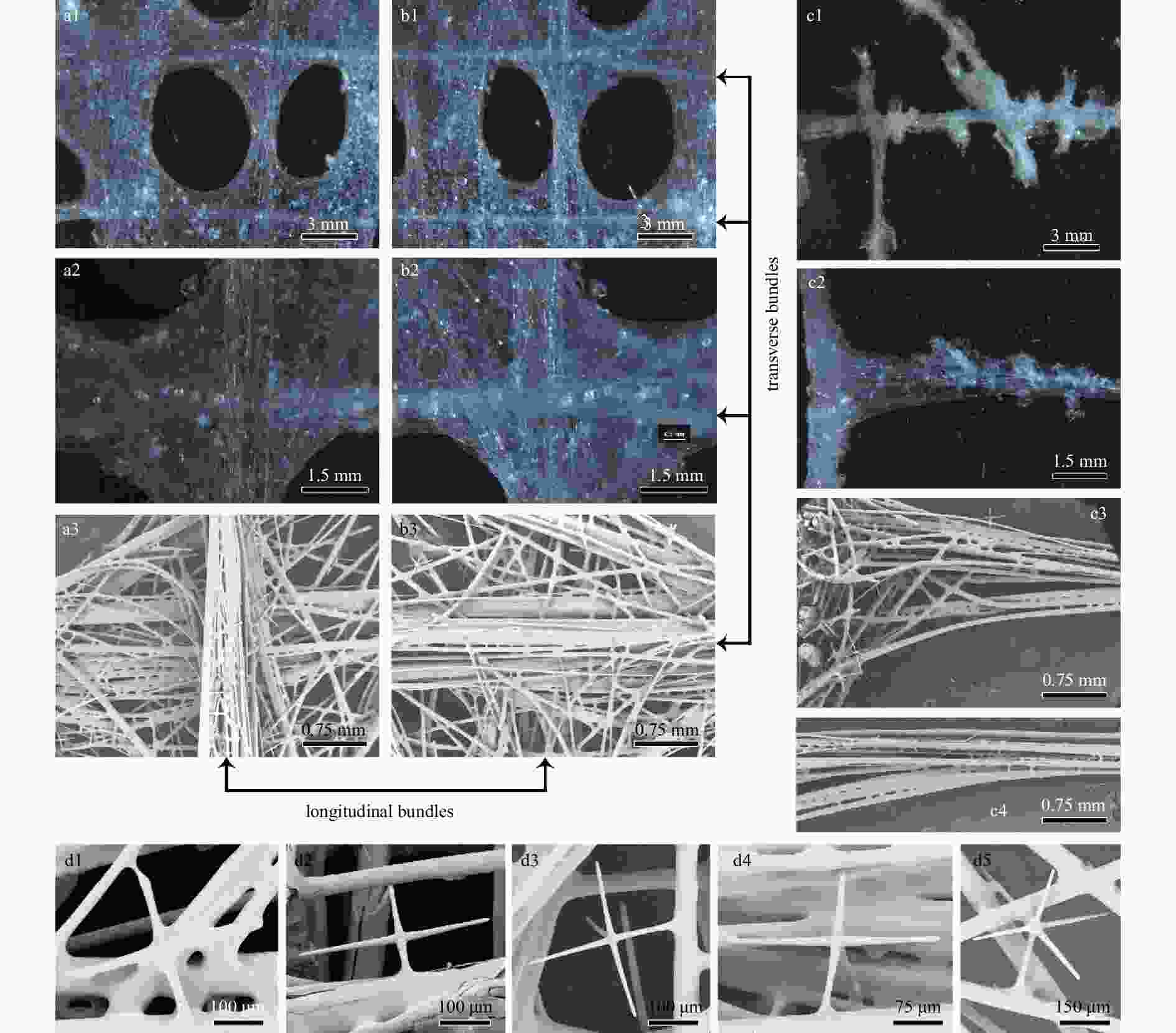

Figure 3. Walteria demeterae sp. nov., surfaces of holotype. Dermal surface of body wall with lateral oscula (a1), close-up image of crossing longitudinal and transverse bundles (a2), and SEM of longitudinal bundles (a3); atrial surface of body wall with lateral oscula (b1), close-up image of crossing longitudinal and transverse bundles (b2), and SEM of transverse bundles (b3); lateral processes of dichotomously branching (c1) or simple (c2) outgrowths, the SEM of framework at junction of body wall and lateral process (c3) and its fused diactins (c4); attached stauractins (d1, d2), pentactins (d3, d4) and occasionally hexactins (d5).

Figure 4. Walteria demeterae sp. nov., spicules. a. Choanosomal diactin, whole and enlargements of three types of rays and middle segments; b. choanosomal stauractin, whole and enlargements of axial centre and two types of rays; c. dermal sword hexactin, whole and enlargements of tangential, proximal and two types of distal rays; d. atrial pentactin, whole and enlargements of axial centre, proximal ray, and two types of tangential rays with a smooth or slightly rough tip; e. oxyhexactins, which are sparsely covered by fine spines (located all over the body, e1) or entirely covered by macrospines (restricted to the basal part, e2), whole and enlargements of centres and rays; f. graphiocome, primary centre and terminal ray at same scale, enlargements of primary centre and both the basal part and tip of terminal ray; g. discohexasters in common dense form or rare sparse form (corresponding to “discohexaster 1” and “discohexaster 2” described for W. flemmingii and W. leuckarti by Reiswig and Kelly, 2018), whole and enlargements of terminal ray and disc; h. onychohexaster, whole and enlargements of six types of onychoid tips with 1–5 claws; i. floricome, whole (not intact) and enlargements of terminal ray and tip.

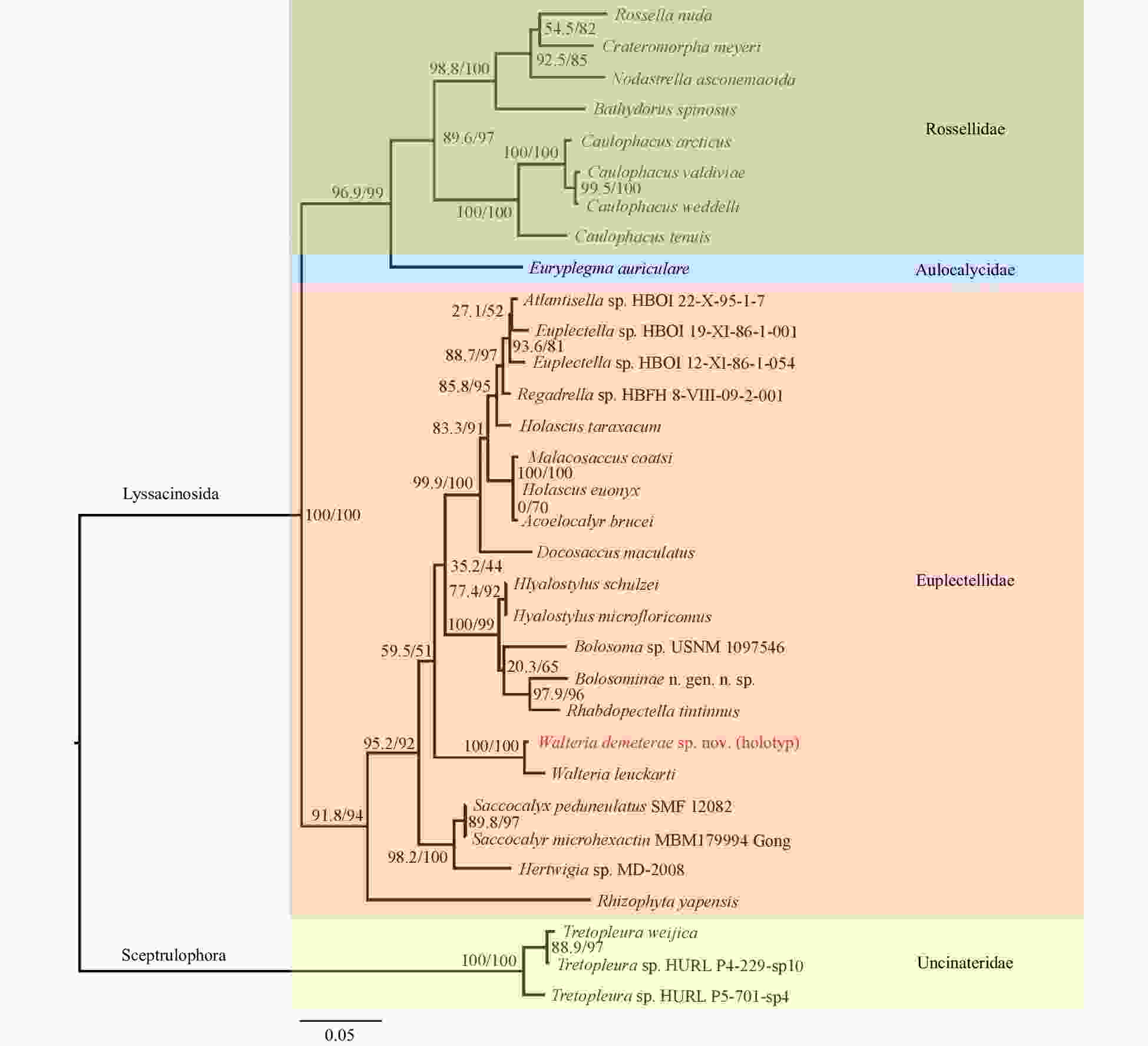

Figure 5. Maximum-likelihood phylogenetic tree of 32 species from four families of Class Hexactinellida (by taking three species of the genus Tretopleuraas as outgroups), showing the relationships of the species Walteria demeterae sp. nov. and related taxa. The tree was inferred from the concatenated alignments of 18S rDNA, 28S rDNA, 16S rDNA and COI. Numbers at nodes are SH-aLRT/ UFBoot support values (all based on 1 000 replicates).

Table 1. GenBank accession numbers of marker genes of the 32 species used in the molecular phylogenetic analysis

Order: family Species Voucher number Accession number 18S rDNA 28S rDNA 16S rDNA COI gene Lyssacinosida: Euplectellidae Walteria demeterae sp. nov. (holotype) SIO-POR-244 MW652662 MW652660 MW652655 MW517848 Walteria leuckarti SMF 10522 AM886399 AM886373 AM886337 FR848939 Docosaccus maculatus GW5429 FM946116 FM946115 FM946105 FR848934 Rhabdopectella tintinnus HBOI 4-X-88-2-014 AM886402 AM886371 AM886332 FR848941 Regadrella sp. HBFH 8-VIII-09-2-001 / FR848916 FR848917 / Rhizophyta yapensis SIO-POR-083 MK463603 MK463607 MK458682 MK453399 Acoelocalyx brucei SMF 10530 AM886401 AM886370 AM886333 FR848938 Malacosaccus coatsi SMF 10521 AM886400 AM886369 AM886334 FR848937 Euplectella sp. 1 HBOI 19-XI-86-1-001 AM886397 AM886368 AM886335 FR848935 Euplectella sp. 2 HBOI 12-XI-86-1-054 AM886398 AM886367 AM886336 / Saccocalyx microhexactin MBM179994 / / KM881702 / Saccocalyx pedunculatus SMF 12082 MF740862 MF684009 MF683987 / Hertwigia sp. USNM 1122181 FM946121 FM946120 FM946104 FR848940 Bolosoma sp. USNM 1097546 FM946118 FM946117 FM946102 FR848942 Bolosominae n. gen. n. sp. HURL P4-224-sp7 / LT627534 LT627520 LT627552 Atlantisella sp. HBOI 22-X-95-1-7 LT627547 LT627533 LT627519 / Holascus euonyx SMF12092 MF740859 / MF683980 / Holascus taraxacum SMF12059 / MF684005 MF683982 / Hyalostylus microfloricomus SMF12085 MF740860 MF684007 MF683984 / Hyalostylus schulzei SMF11707 / / MF683985 / Lyssacinosida: Rossellidae Rossella nuda SMF 10531 AM886384 AM886355 AM886343 HE580217* Nodastrella asconemaoida ZMA POR18484 AM886386 AM886354 AM886344 FR848921 Caulophacus arcticus SMF 10520 AM886395 AM886360 AM886350 FR819684 Caulophacella tenuis SMF 10533 AM886392 AM886363 AM886351 FR848927 Caulophacus valdiviae SMF 10528 AM886394 AM886362 AM886348 FR848929 Caulophacus weddelli SMF 10527 AM886393 AM886361 AM886349 FR848928 Crateromorpha meyeri SMF 10525 AM886389 AM886359 AM886347 FR848923 Bathydorus spinosus SMF 10526 AM886390 AM886358 AM886341 FR848924 Lyssacinosida: Aulocalycidae Euryplegma auriculare NIWA 43457 / LT627535 LT627518 LT627551 Sceptrulophora: Uncinateridae Tretopleura weijica SIO-POR-090 / / MT176124 MT178277 Tretopleura sp. 1 HURL P4-229-sp10 / LT627542 LT627529 LT627556 Tretopleura sp. 2 HURL P5-701-sp4 / LT627543 LT627530 LT627555 Note: The symbol “*” refers that the COI gene of Rossella nuda was from the voucher SMF 11730. Table 2. Spicule dimensions of Walteria demeterae sp. nov., holotype

Spicule Dimension Mean S.D. Min Max N Choanosomal diactin length/µm 1 071.4 881.9 451.0 4 300.0 30 width/µm 14.0 3.4 8.0 27.5 30 Choanosomal stauractin long ray length/µm 265.9 164.7 168.5 738.9 11 short ray length/µm 157.6 32.7 107.5 211.3 11 ray width/µm 14.2 2.9 8.8 18.5 11 Dermal sword hexactin (lateral processes) distal ray length/µm 172.0 44.8 88.9 275.0 30 distal ray basal width/µm 15.2 2.1 11.1 20.0 30 distal ray maximum width/µm 19.4 3.8 14.0 30.0 30 tangential ray length/µm 122.3 24.6 72.2 186.0 30 tangential ray width/µm 13.2 1.3 9.3 15.3 30 proximal ray length/µm 506.6 140.2 243.3 882.0 30 proximal ray width/µm 14.5 1.4 11.3 17.3 30 Dermal sword hexactin (body wall) distal ray length/µm 136.2 53.0 49.2 215.0 14 distal ray basal width/µm 15.1 3.8 7.4 22.7 14 distal ray maximum width/µm 19.4 5.8 10.0 33.3 14 tangential ray length/µm 121.7 46.5 64.3 215.3 14 tangential ray width/µm 13.1 3.4 6.8 18.0 14 proximal ray length/µm 431.9 181.2 114.0 686.7 14 proximal ray width/µm 13.6 3.0 6.4 18.7 14 Atrial pentactin tangential ray length/µm 158.0 30.7 111.5 225.0 30 tangential ray width/µm 13.7 2.6 8.3 18.7 30 proximal ray length/µm 310.2 137.2 83.3 654.0 30 proximal ray width/µm 14.8 3.2 8.3 21.7 30 Oxyhexactin ray length/µm 180.3 35.7 115.0 265.0 40 ray width/µm 8.0 2.1 3.9 12.4 40 Oxyhexactin (base) ray length/µm 117.7 29.8 71.5 195.3 30 ray width/µm 3.0 0.5 2.3 4.0 30 spine max. length/µm 7.1 2.3 3.0 12.0 30 Graphiocome centre diameter/µm 25.6 1.8 22.7 29.7 30 primary ray length/µm 7.5 0.8 6.3 10.0 30 primary ray width/µm 2.1 0.2 1.8 2.5 30 raphide length/µm 158.9 13.2 100.0 179.0 50 Discohexaster diameter/µm 88.9 6.6 77.5 110.0 30 primary ray length/µm 5.8 1.2 3.5 9.0 30 secondary ray length/µm 35.7 2.8 30.0 46.1 30 Onychohexaster diameter/µm 83.0 8.8 70.0 100.0 25 primary ray length/µm 4.1 0.9 2.5 6.7 25 secondary ray length/µm 37.0 3.9 30.0 45.2 25 Floricome diameter/µm 122.1 54.0 84.7 184.0 3 primary ray length/µm 5.8 2.3 3.8 8.3 3 secondary ray length/µm 53.5 26.4 33.3 83.3 3 -

[1] Bankevich A, Nurk S, Antipov D, et al. 2012. SPAdes: a new genome assembly algorithm and its applications to single-cell sequencing. Journal of Computational Biology, 19(5): 455–477. doi: 10.1089/cmb.2012.0021 [2] Beazley L I, Kenchington E L, Murillo F J, et al. 2013. Deep-sea sponge grounds enhance diversity and abundance of epibenthic megafauna in the Northwest Atlantic. ICES Journal of Marine Science, 70(7): 1471–1490. doi: 10.1093/icesjms/fst124 [3] Bell J J. 2008. The functional roles of marine sponges. Estuarine, Coastal and Shelf Science, 79(3): 341–353 [4] Chernomor O, von Haeseler A, Minh B Q. 2016. Terrace aware data structure for phylogenomic inference from supermatrices. Systematic Biology, 65(6): 997–1008. doi: 10.1093/sysbio/syw037 [5] de Voogd N J, Alvarez B, Boury-Esnault N, et al. 2021. World Porifera Database. Corbitellinae Gray, 1872. http://www.marinespecies.org/porifera/porifera.php?p=taxdetails&id=171848 [2021-10-27] [6] Dohrmann M, Janussen D, Reitner J, et al. 2008. Phylogeny and evolution of glass sponges (Porifera, Hexactinellida). Systematic Biology, 57(3): 388–405. doi: 10.1080/10635150802161088 [7] Dohrmann M, Kelley C, Kelly M, et al. 2017. An integrative systematic framework helps to reconstruct skeletal evolution of glass sponges (Porifera, Hexactinellida). Frontiers in Zoology, 14: 18. doi: 10.1186/s12983-017-0191-3 [8] Dohrmann M. 2019. Progress in glass sponge phylogenetics: a comment on Kersken et al. (2018). Hydrobiologia, 843: 51–59. doi: 10.1007/s10750-018-3708-7 [9] Folmer O, Black M, Hoeh W, et al. 1994. DNA primers for amplification of mitochondrial cytochrome c oxidase subunit I from diverse metazoan invertebrates. Molecular Marine Biology and Biotechnology, 3(5): 294–299 [10] Grant R E. 1836. Animal kingdom. In: Todd R B, ed. The Cyclopaedia of Anatomy and Physiology. Vol 1. London: Sherwood, Gilbert, and Piper, 107–118 [11] Gray J E. 1867. Notes on the arrangement of sponges, with the descriptions of some new genera. Proceedings of the Zoological Society of London, 1867(2): 492–558, pls XXVII–XXVIII [12] Gray J E. 1872. XX. —On a new genus of hexaradiate and other sponges discovered in the Philippine Islands by Dr. A. B. Meyer. Annals and Magazine of Natural History, 10(56): 134–139. doi: 10.1080/00222937208696659 [13] Guindon S, Dufayard J F, Lefort V, et al. 2010. New algorithms and methods to estimate maximum-likelihood phylogenies: assessing the performance of PhyML 3.0. Systematic Biology, 59(3): 307–321. doi: 10.1093/sysbio/syq010 [14] Hajdu E, Castello-Branco C, Lopes D A, et al. 2017. Deep-sea dives reveal an unexpected hexactinellid sponge garden on the Rio Grande Rise (SW Atlantic). A mimicking habitat?. Deep-Sea Research Part II: Topical Studies in Oceanography, 146: 93–100. doi: 10.1016/j.dsr2.2017.11.009 [15] Hoang D T, Chernomor O, von Haeseler A, et al. 2018. UFBoot2: improving the ultrafast bootstrap approximation. Molecular Biology and Evolution, 35(2): 518–522. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msx281 [16] Ijima I. 1896. Notice of new Hexactinellida from Sagami Bay: II. Zoologischer Anzeiger, 19: 249–254 [17] Kou Qi, Gong Lin, Li Xinzheng. 2018. A new species of the deep-sea spongicolid genus Spongicoloides (Crustacea, Decapoda, Stenopodidea) and a new species of the glass sponge genus Corbitella (Hexactinellida, Lyssacinosida, Euplectellidae) from a seamount near the Mariana Trench, with a novel commensal relationship between the two genera. Deep-Sea Research Part I: Oceanographic Research Papers, 135: 88–107. doi: 10.1016/j.dsr.2018.03.006 [18] MacIntosh H, Althaus F, Williams A, et al. 2018. Invertebrate diversity in the deep Great Australian Bight (200–5 000m). Marine Biodiversity Records, 11: 23. doi: 10.1186/s41200-018-0158-x [19] Minh B Q, Nguyen M A T, von Haeseler A. 2013. Ultrafast approximation for phylogenetic bootstrap. Molecular Biology and Evolution, 30(5): 1188–1195. doi: 10.1093/molbev/mst024 [20] Na Jieying, Chen Wanying, Zhang Dongsheng, et al. 2021. Morphological description and population structure of an ophiuroid species from cobalt-rich crust seamounts in the Northwest Pacific: implications for marine protection under deep-sea mining. Acta Oceanologica Sinica, 40(8): 1–11. doi: 10.1007/s13131-021-1804-4 [21] Nguyen L T, Schmidt H A, von Haeseler A, et al. 2015. IQ-TREE: a fast and effective stochastic algorithm for estimating maximum-likelihood phylogenies. Molecular Biology and Evolution, 32(1): 268–274. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msu300 [22] Rambaut A. 2006. FigTree v1.4. 2. Computer software and manual. http://tree.bio.ed.ac.uk/software/figtree [2014-07-09/2021-09-01] [23] Reiswig H M, Kelly M. 2018. The marine fauna of New Zealand. Euplectellid glass sponges (Hexactinellida, Lyssacinosida, Euplectellidae). NIWA Biodiversity Memoir, 130: 1–170 [24] Schmidt O. 1870. Grundzüge einer Spongien-Fauna des atlantischen Gebietes (in German). Leipzig: Wilhelm Engelmann, 1–88 [25] Schulze F E. 1886. Über den Bau und das System der Hexactinelliden. Abhandlungen der Kö niglichen Akademie der Wissenschaften zu Berlin (Physikalisch-Mathematische Classe) (in German), 1–97 [26] Schulze F E. 1887. Report on the Hexactinellida collected by H. M. S. ‘Challenger’ during the years 1873–76. Report on the Scientific Results of the Voyage of H. M. S. Challenger during the years 1873–76. Zoology, 21(part 53): 1–514 [27] Shen Chengcheng, Dohrmann M, Zhang Dongsheng, et al. 2019. A new glass sponge genus (Hexactinellida: Euplectellidae) from abyssal depth of the Yap Trench, northwestern Pacific Ocean. Zootaxa, 4567(2): 367–378. doi: 10.11646/zootaxa.4567.2.9 [28] Tabachnick K, Fromont J, Ehrlich H, et al. 2019. Hexactinellida from the Perth Canyon, eastern Indian Ocean, with descriptions of five new species. Zootaxa, 4664(1): 47–82. doi: 10.11646/zootaxa.4664.1.2 [29] Tabachnick K R. 1988. Hexactinellid sponges from the mountains of the West Pacific. In: Shirshov P P, ed. Structural and Functional Researches of the Marine Benthos. Moscow: Academy of Sciences of the USSR, 49–64 [30] Tabachnick K R. 2002. Family Euplectellidae Gray, 1867. In: Hooper J N A, Van Soest R W M, Willenz P, eds. Systema Porifera: A Guide to the Classification of Sponges. Boston, MA: Springer, 1388–1434 [31] Xu Peng, Zhou Yadong, Wang Chunsheng. 2017. A new species of deep-sea sponge-associated shrimp from the North-West Pacific (Decapoda, Stenopodidea, Spongicolidae). ZooKeys, 685: 1–14. doi: 10.3897/zookeys.685.11341 [32] Zittel K A. 1877. Studien über fossile Spongien. In: Hexactinellidae. Abhandlungen der Königlich Bayerischen Akademie der Wissenschaften, Mathematisch-Physikalisch Klasse (in German), 13(1): 1–63 -

下载:

下载: