| Factor | Name | Level | Low level | High level |

| A | C/N concentration ratio | 4.0 | 2.0 | 6.0 |

| B | pH | 7.5 | 6.0 | 9.0 |

| C | NaCl/% | 2.5 | 0.0 | 5.0 |

| D | temperature/°C | 10.0 | 5.0 | 15.0 |

| Citation: | Guizhen Li, Qiliang Lai, Guangshan Wei, Peisheng Yan, Zongze Shao. Simultaneous nitrification and denitrification conducted by Halomonas venusta MA-ZP17-13 under low temperature conditions[J]. Acta Oceanologica Sinica, 2021, 40(9): 94-104. doi: 10.1007/s13131-021-1897-9 |

Nitrogen (N) compounds are indispensable in biological metabolic processes and play vital roles in nutrient cycling. Inorganic ammonium (

Generally, the treatment of

In recent years, bacteria capacity of simultaneous nitrification and denitrification (SND) have been identified from various environments (Hooper et al., 1997). Many bacteria capacity of SND have been studied from biological N removal systems (Zhao et al., 2010a; Yao et al., 2013; Ren et al., 2014; He et al., 2016; Yu et al., 2016). However, most of these nitrifying strains were mainly carried out under mesophilic conditions (around 30°C) (Zhao et al., 2010b; Chen and Ni, 2012; Huang et al., 2013). Nitrification was strongly inhibited at temperatures below 10°C (Carrera et al., 2003; Rodriguez-Caballero et al., 2012; Huang et al., 2013). Therefore,

To obtain bacteria that are capable of effective

Surface seawater of higher-place P. vannamei ponds was sampled in June 2018. The aquaculture seawater sample (24.02°N, 117.83°E) was obtained from an aquaculture farm in Zhangpu County, Zhangzhou City, Fujian Province, China. The seawater was diluted and spread on heterotrophic nitrification medium (HNM) (Xu et al., 2017). After 4 d of aerobic incubation at 28°C, single colonies were picked. Purity was confirmed by the uniformity of cell morphology after repeated streaking. During bacterial screening process, a strain named MA-ZP17-13 was isolated along with many other bacterial isolates. For morphological and biochemical characterization, strain MA-ZP17-13 was cultivated on marine agar 2216 medium. For long-time storage, the strain was suspended in 20.0% glycerol solution at −80°C and deposited in Marine Culture Collection of China under accession number MCCC 1A14584.

Marine agar 2216 medium (BD Difco) (Li et al., 2019) contained (per L): 5.0 g peptone, 1.0 g yeast extract, 0.1 g FeC6H5O7, 19.45 g NaCl, 8.8 g MgCl2, 3.24 g Na2SO4, 1.8 g CaCl2, 0.55 g KCl, 0.16 g NaHCO3, 0.08 g KBr, 34.0 mg SrCl2, 22.0 mg H3BO3, 4.0 mg Na2SiO3, 2.4 mg NaF, 1.6 mg NH4NO3, 8.0 mg Na2HPO4.

HNM (pH=7.2) (Xu et al., 2017) contained (per L): 0.24 g (NH4)2SO4, 1.12 g C4H4Na2O4·6H2O, 0.05 g MgSO4·7H2O, 0.5 g KH2PO4, 2.5 g K2HPO4, 30 g NaCl, 0.05 g MnSO4, 0.05 g FeSO4 and 1 mL trace element solution. HNM medium (inorganic medium) was used to determine the

Denitrification medium (DM; pH = 7.2) (Xu et al., 2017) contained (per L) : 1.08 g KNO3, 8.43 g C4H4Na2O4·6H2O, 7.9 g Na2HPO4·7H2O, 1.5 g KH2PO4, 0.1 g MgSO4·7H2O, 30 g NaCl, 1 mL trace element solution. The isolate was cultivated in DM medium to test the ability of denitrification.

Trace element solution contained (per L): 2 mg CaCl2, 50 mg FeCl3·6H2O, 0.5 mg CuSO4, 0.5 mg MnCl2·4H2O and 10 mg ZnSO4·7H2O. Cultures were incubated at 10°C and spun at 150 r/min, unless noted otherwise.

The strain MA-ZP17-13 was activated on marine agar 2216 plates, and inoculated into 100 mL marine broth 2216 medium and cultured at 150 r/min and 10°C for 24 h. The culture of 2 mL was centrifuged to remove the medium and washed twice with sterilized seawater, then inoculated into 100 mL HNM medium for ammonia removal tests. After incubated at 10°C and 150 r/min for 15 h under aerobic conditions, 5 mL liquid cultures were sampled serially at intervals of several hours to detect the concentrations of

The

To detect bacterial ammonia assimilation, strain MA-ZP17-13 was cultured in HNM at 150 r/min and 10°C for 72 h in 100 mL flask. After centrifugation and freeze-drying, the intracellular N content was detected by elemental analyzer EL-III (Vario EL-III). The intracellular N content was calculated by the formula as follows: R=R1×M/V, where R (mg/L), R1 (%), M (mg) and V (L) represented

The concentrations of

For genome sequencing, strain MA-ZP17-13 was grown aerobically to mid logarithmic phase at 10°C on marine agar 2216 medium. Genomic DNA was isolated from the cell pellets using the ChargeSwitch® gDNA Mini Bacteria Kit (Life Technologies) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Purified genomic DNA was quantified by TBS-380 fluorometer (Turner BioSystems, CA). High quality DNA (OD260/280 is 1.8−2.0, >10 μg) was used to do further research.

The genome of strain MA-ZP17-13 was sequenced using a combination of PacBio RS and Illumina sequencing platforms. The Illumina data was used to evaluate the complexity of the genome. These data were tried to be assembled using Velvet assembler (v1.2.09) with a k-mer length of 17 (Zerbino, 2010). The complete genome sequence was assembled using both the PacBio reads and Illumina reads. The assembly was produced firstly using a hybrid de novo assembly solution modified by Koren (Koren et al., 2012), in which a de-Bruijn based assembly algorithm and a CLR (continuous long reads) reads correction algorithm were integrated in “PacBioToCA with Celera Assembler” pipeline (Chin et al., 2013). The last circular step was checked and finished manually. The final assembly generated a circular genome sequence with no gap. The complete genome sequence was submitted to GenBank under accession No. CP034367.

Identification of predicted coding sequences (CDS), also called open reading frames (ORFs), was performed using Glimmer version 3.02. ORFs with less than 300 bp were discarded. Then remaining ORFs were queried against the non-redundant (NR) protein database in the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI), SwissProt (http://uniprot.org), Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG,

Gene prediction and annotation were performed using the NCBI prokaryotic genome annotation pipeline (Tatusova et al., 2016) and six large databases (NR, Swiss-Prot, Pfam, COG, GO, and KEGG). The functional annotation of predicted ORFs was used to search the KEGG and COG databases by RPS-BLAST.

The average nucleotide identity (ANI) between strains MA-ZP17-13 and H. venusta DSM 4743T was calculated with EZGenome using the algorithm of Goris et al. (2007). DNA-DNA hybridization (DDH) estimate values between two strains were analyzed using the genome-to-genome distance calculator (GGDC2.0) (Auch et al., 2010a, b; Meier-Kolthoff, et al., 2013).

The critical factors affecting

Based on the preliminary results, the appropriate range of independent variables including C/N concentration ratio (A), pH (B), salinity (C) and temperature (D) were determined. The response surface methodology is an important math-statistics technique for designing, modeling and analysis of problems where a response of interest is affected by several different parameters (Qu et al., 2017). Design expert 8.0.5b software was used for the design of the experimental run (Myers et al., 2016). Box-Behnken design (BBD) was applied to generate the design matrix of four factors at three levels (Table 1). Twenty-nine BBD trials were conducted to provide direction for further optimization studies (Table 2). Analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to check the validity of regression model and determine the quadratic effect of machine parameters on the output response function.

| Factor | Name | Level | Low level | High level |

| A | C/N concentration ratio | 4.0 | 2.0 | 6.0 |

| B | pH | 7.5 | 6.0 | 9.0 |

| C | NaCl/% | 2.5 | 0.0 | 5.0 |

| D | temperature/°C | 10.0 | 5.0 | 15.0 |

| Independent variables | Response | |||||

| Run | A | B | C | D | Ammonia removal Y1/% | |

| C/N concentration ratio | pH | NaCl/% | Temperature /°C | |||

| 1 | 2 | 6 | 2.5 | 10 | 40.3 | |

| 2 | 6 | 6 | 2.5 | 10 | 62.5 | |

| 3 | 2 | 9 | 2.5 | 10 | 52.4 | |

| 4 | 6 | 9 | 2.5 | 10 | 100.0 | |

| 5 | 4 | 7.5 | 0 | 5 | 68.0 | |

| 6 | 4 | 7.5 | 5 | 5 | 36.2 | |

| 7 | 4 | 7.5 | 0 | 15 | 70.3 | |

| 8 | 4 | 7.5 | 5 | 15 | 68.0 | |

| 9 | 2 | 7.5 | 2.5 | 5 | 36.0 | |

| 10 | 6 | 7.5 | 2.5 | 5 | 50.1 | |

| 11 | 2 | 7.5 | 2.5 | 15 | 37.5 | |

| 12 | 6 | 7.5 | 2.5 | 15 | 83.9 | |

| 13 | 4 | 6 | 0 | 10 | 59.8 | |

| 14 | 4 | 9 | 0 | 10 | 84.4 | |

| 15 | 4 | 6 | 5 | 10 | 54.9 | |

| 16 | 4 | 9 | 5 | 10 | 77.7 | |

| 17 | 2 | 7.5 | 0 | 10 | 51.0 | |

| 18 | 6 | 7.5 | 0 | 10 | 87.7 | |

| 19 | 2 | 7.5 | 5 | 10 | 43.1 | |

| 20 | 6 | 7.5 | 5 | 10 | 82.4 | |

| 21 | 4 | 6 | 2.5 | 5 | 18.5 | |

| 22 | 4 | 9 | 2.5 | 5 | 59.3 | |

| 23 | 4 | 6 | 2.5 | 15 | 40.0 | |

| 24 | 4 | 9 | 2.5 | 15 | 74.2 | |

| 25 | 4 | 7.5 | 2.5 | 10 | 67.0 | |

| 26 | 4 | 7.5 | 2.5 | 10 | 67.0 | |

| 27 | 4 | 7.5 | 2.5 | 10 | 67.0 | |

| 28 | 4 | 7.5 | 2.5 | 10 | 67.0 | |

| 29 | 4 | 7.5 | 2.5 | 10 | 67.0 | |

Statistical model analysis was evaluated to determine the ANOVA and the quadratic models were constituted as 3D contour plots using Design-Expert® 8 software (Myers et al., 2016).

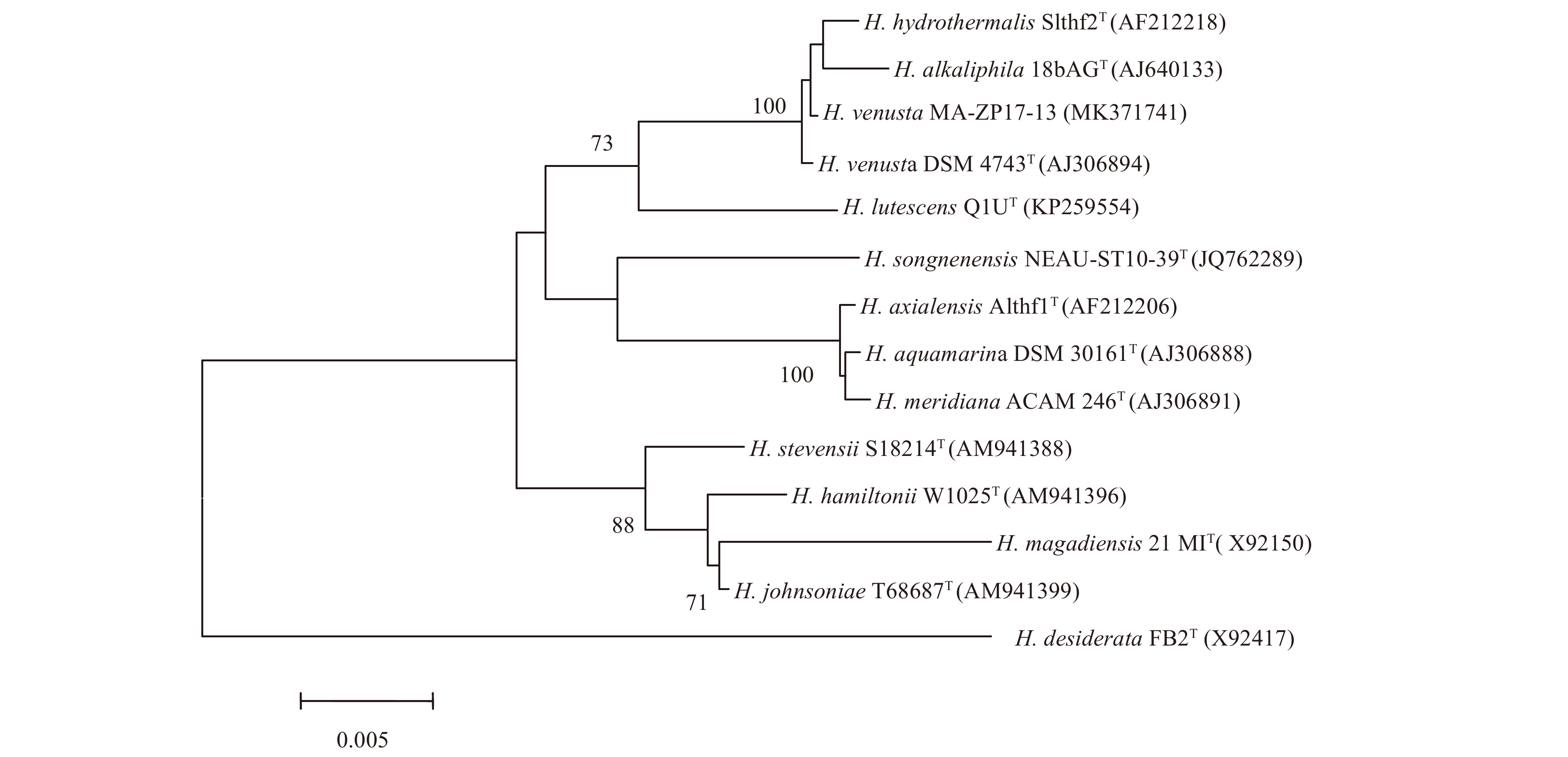

A nearly full-length 16S rRNA gene sequence (1 540 nt) of strain MA-ZP17-13 was determined, which showed the highest sequence similarity to H. venusta DSM 4743T (99.93%), followed by H. hydrothermalis Slthf2T (99.79%) and H. alkaliphila 18bAGT (99.73%). A phylogenetic tree was constructed based on the 16S rRNA gene sequences of the genus Halomonas (Fig. 1), which showed that strain MA-ZP17-13 formed a clade with H. venusta DSM 4743T. The data DNA-DNA hybridization estimate value between strain MA-ZP17-13 and H. venusta DSM 4743T was 90.80%, which was above the standard cut-off value (70%) (Wayne et al., 1987). The ANI value between strain MA-ZP17-13 and H. venusta DSM 4743T was 98.78%, which was above the standard ANI criteria for species identity (95%–96%) (Richter and Rosselló-Móra, 2009). Hence, strain MA-ZP17-13 was identified as H. venusta based on 16S rRNA gene sequence analyses and dDDH value.

On marine agar 2216, colonies of strain MA-ZP17-13 are milk white, opaque, convex, regular with entire margin and 1.0–2.0 mm in diameter after 2 d at 28°C. General features of strain MA-ZP17-13 are summarized in Table 3.

| Items | Description |

| General features | |

| Classification | domains: Bacteria, phylum: Proteobacteria, class: Gammaproteobacteria, order: Oceanospirillales, family: Halomonadaceae, genus: Halomonas, species: Halomonas venusta |

| Gram stain | negative |

| Cell shape | rod |

| Motility | motile |

| Pigmentation | no-pigment |

| Temperature range/°C | 4−55 |

| Optimum temperature/°C | 28−37 |

| Energy source | chemoorganotrophic |

| Terminal electron receptor | oxygen |

| Oxygen | aerobic |

| NaCl content/% | 0−15 |

| pH | 5.0−10.0 |

| MIGS data | |

| Submitted to INSDC | GenBank (ID: CP034367) |

| Investigation type | bacteria |

| Project name | Halomonas venusta strain: MA-ZP17-13 genome sequencing |

| Geographic location (country) | China |

| Collection date | 2018 |

| Environment (biome) | seawater farms |

| Environment (feature) | water |

| Environment (material) | seawater |

| Environmental package | mariculture samples from Zhangzhou, China |

| Biotic relationship | free-living |

| Pathogenicity | none |

| Sequencing method | PacBio RS, Illumina Hiseq2000 |

| Assembly | GS De Novo Assembler package |

| Finishing strategy | complete |

| Note: INSDC represents International Nucleotide Sequence Database Collaboration. | |

The strain is positive for catalase and oxidase, reduction of nitrate and denitrification, and is negative for arginine dihydrolase, indole production, D-glucose fermentation, urease, β-galactosidase. API ZYM test strip results indicate that it is positive for alkaline phosphatase, esterase (C4), lipase (C14), leucine aminopeptidase, naphtol-AS-BI-phosphoamidase, valine aminopeptidase, acid phosphatase, α-glucosidase; it is weakly positive for esterase lipase (C8), cystine aminopeptidase; it is negative for N-acetyl-β-glucosaminidase, trypsin, α-chymotrypsin, α-galactosidase, β-galactosidase, β-glucuronidase, β-glucosidase, α-fucosidase and α-mannosidase. The API 20NE test strip shows that strain MA-ZP17-13 can utilize D-glucose, D-mannitol, D-maltose, N-acetyl-glucosamine, potassium gluconate, capric acid, adipic acid, malic acid, trisodium citrate and phenylacetic acid, cannot utilize L-arabinose and D-mannose.

Low temperature can reduce

The

To determine nitrification efficiency of this bacterium at low temperature, ammonia was used as the only N source in HNM medium under aerobic conditions at 10°C, with an initial concentration of 100 mg/L

To determine its

In conclusion, strain MA-ZP17-13 is capable of SND under low temperature. Compared with traditional denitrifying strains, SND has advantages such as high

Based on the single-factor experiments, a complete experimental design matrix was developed by BBD for further optimizations of the four parameters. The values of the response gained from the experiment were shown in Table 2. The

| $$\begin{split} R1 =\ & 67.0 + {\rm{17}}{\rm{.19A + 14}}{{.33{\rm{B}} - 4}}{\rm{.91C + 8}}{\rm{.82D + 6}}{\rm{.35AB + }}\\ & {\rm{0.65AC + 8}}{{.07{\rm{AD}} - 0}}{{.45{\rm{BC}} - 1}}{\rm{.65BD + 7}}{{.38{\rm{CD}} }}\ - \\ &{\rm{2.56}}{{\rm{A}}^{\rm{2}}}{{ - 2}}{\rm{.92}}{{\rm{B}}^{\rm{2}}}{\rm{ + 4}}{\rm{.51}}{{\rm{C}}^{\rm{2}}}{{ - 13}}{\rm{.18}}{{\rm{D}}^{\rm{2}}}{\rm{.}} \end{split} $$ | (1) |

The accuracy of the established regression models was then assessed by the correlation coefficient R2, with values closer to 1, indicating a more precise response value estimated by the models. The R2 value for Eq. (1) was 0.96 and the predicted values versus the corresponding experimental values for Y1 were shown in Fig. 5. As expected, the actual values were consistent with the predicted values, implying that the models successfully predicted the relationships between culture parameters and

In addition to the correlation coefficients, F-values and P-values were employed to determine the significance of the models and each model term, with a larger F-value indicating increased significance of the corresponding coefficient (Zhou et al., 2013). The ANOVA of the predicted quadratic model for

| Source | Sum of squares | Degree of freedom | Mean square | F-value | P |

| Model | 9 366.15 | 14 | 669.01 | 27.57 | < 0.000 1 |

| A (C/N concentration ratio) | 3 546.64 | 1 | 3 546.64 | 146.17 | < 0.000 1 |

| B (pH) | 2 465.33 | 1 | 2 465.33 | 101.61 | < 0.000 1 |

| C (NaCl) | 289.10 | 1 | 289.10 | 11.92 | 0.003 9 |

| D (temperature) | 932.80 | 1 | 932.80 | 38.45 | < 0.000 1 |

| AB | 161.29 | 1 | 161.29 | 6.65 | 0.021 9 |

| AC | 1.69 | 1 | 1.69 | 0.07 | 0.795 7 |

| AD | 260.82 | 1 | 260.82 | 10.75 | 0.005 5 |

| BC | 0.81 | 1 | 0.81 | 0.03 | 0.857 6 |

| BD | 10.89 | 1 | 10.89 | 0.45 | 0.513 8 |

| CD | 217.56 | 1 | 217.56 | 8.97 | 0.009 7 |

| A2 | 42.59 | 1 | 42.59 | 1.76 | 0.206 4 |

| B2 | 55.50 | 1 | 55.50 | 2.29 | 0.152 7 |

| C2 | 132.08 | 1 | 132.08 | 5.44 | 0.035 1 |

| D2 | 1 125.93 | 1 | 1 125.93 | 46.40 | < 0.000 1 |

| Residual | 339.68 | 14 | 24.26 | − | − |

| Note: −, no data. | |||||

The

The

The

| Strain name | Source | Salinity | Temperature/°C | RTAM/(mg·L−1·h−1) | Reference |

| Acinetobacter sp. HA2 | sediment | 0 | 10.0 | 3.03 | Yao et al. (2013) |

| Acinetobacter sp. Y16 | water | 0.12 | 2.0 | 0.092 | Huang et al. (2013) |

| Pseudomonas migulae AN-1 | water | 0 | 10.0 | 1.56 | Qu et al. (2015) |

| Pseudomonas putida Y-9 | soil | 0 | 15.0 | 2.85 | Xu et al. (2017) |

| H. venusta MA-ZP17-13 | seawater | 23.3 | 11.2 | 1.37 | present study |

| Note: RTAM represents removal rate of total ammonia nitrogen. | |||||

The complete genome sequence of strain MA-ZP17-13 was determined in this study. It consisted of one chromosome with a total length of 4 446 698 bp with a G+C content of 52.79% (according to amount of substance) (Fig. 7). Gene prediction identified 4 330 genes, of which 4 251 were CDSs, and 79 were RNAs (Table 6). The average length of the CDSs was 936 bp, giving a coding density of 96.0%. To further understand the adaptive capacity of strain MA-ZP17-13 to the aquaculture environment, metabolic features related to functional categories were analyzed. Twenty-five genes were found relating to N metabolism, which included nitrification and denitrification (Supplementary Table S1).

| Attribute | Genome (total) value | Proportion of total/% |

| Genome size/bp | 4 446 698 | 100.00 |

| G+C content/bp | 2 347 412 | 52.79 |

| Coding region/bp | 3 979 236 | 89.49 |

| TandemRepeat/bp | 60 444 | 1.52 |

| Total genes | 4 330 | 100.00 |

| RNA genes | 79 | 1.82 |

| rRNA operons | 18 | 0.42 |

| tRNA genes | 61 | 1.41 |

| Protein-coding genes | 4 251 | 98.18 |

| Genes assigned to COGs | 3 676 | 86.47 |

Genes encoding ammonia monooxygenase, nitric oxide dioxygenase, nitric oxide synthase, nitrite reductases, nitrate reductases and dissimilatory nitrite reductases were present in the genome of this strain, indicating that it was capable for both nitrification and denitrification. Consistent with its

Consistent with the abilities of strain MA-ZP17-13, H. alkaliphila X3T was reported to be capable for heterotrophic nitrification-aerobic denitrification (Zhang et al., 2016) and the genome was obtained from NCBI database. These strains shared 99.68% similarity in 16S rRNA gene sequence, but the ANI between the two strains was 93.01%, indicating that the two strains belonged to two different species in genus Halomonas. This study found that H. alkaliphila X3T possessed similar nitrification-related genes and was also lacking hydroxylamine oxidase. The ammonia monooxygenase gene in strain MA-ZP17-13 is also 1 041 bp long and encodes 346 amino acids and is homologous to the corresponding gene in strain X3T with at least 99% amino acid identity. The high sequence similarity of the ammonia monooxygenase gene between strains MA-ZP17-13 and H. alkaliphila X3T indicates similar function and regulation of

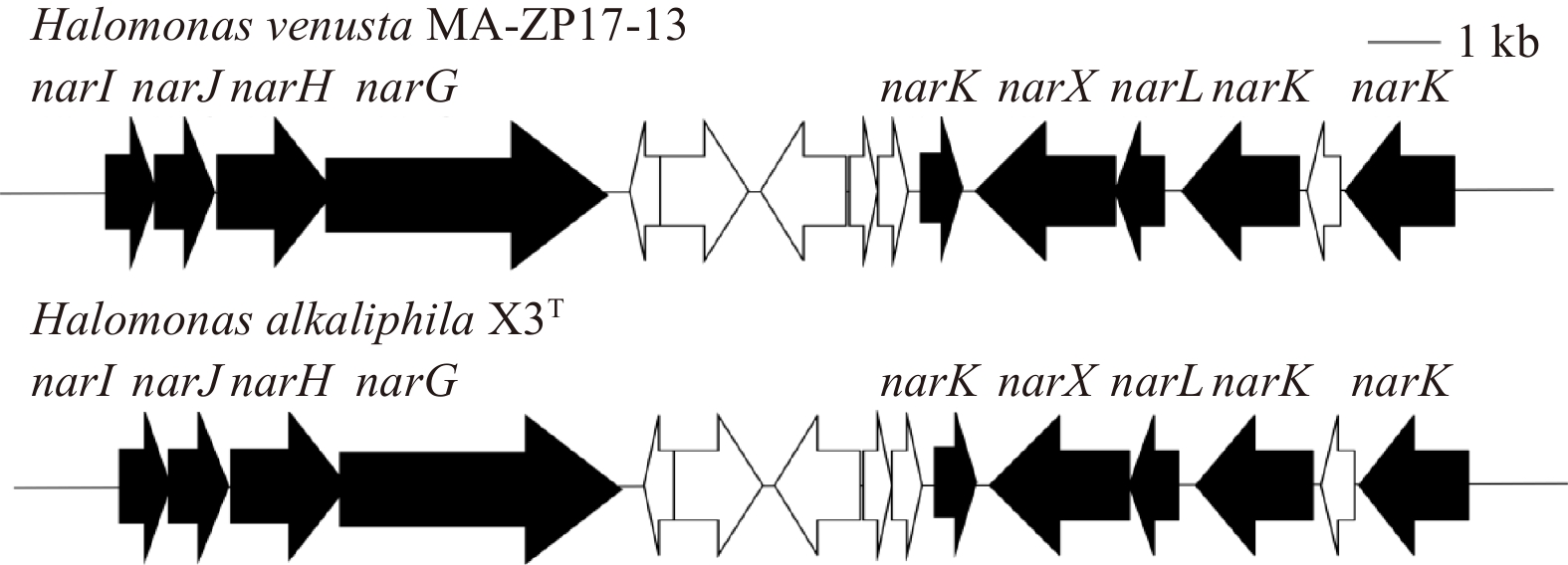

In addition, this study found that the same gene cluster of nitrate reductase was present in strains MA-ZP17-13 and H. alkaliphila X3T. The gene cluster contains the nitrate reductase gamma subunit (narI), nitrate reductase molybdenum cofactor assembly chaperone (narJ), nitrate reductase subunit beta (narH), nitrate reductase subunit alpha (narG), nitrate/nitrite sensor protein (narX), DNA-binding response regulator (narL), and MFS transporter (narK) genes (Fig. 8). Genes of nitrite reductases, nitrate reductases, nitric oxide dioxygenase, nitric oxide synthase, dissimilatory nitrite reductases were present in both strain MA-ZP17-13 and X3T. Validation of the function of these encoding genes requires further study to confirm their abilities and determine the mechanism of nitrification and denitrification, which is currently unknown. Increased understanding of the mechanisms of

The isolated Halomonas venusta MA-ZP17-13 is capable for

| [1] |

APHA. 2005. Standard Methods for the Examination of Water and Wastewater. 21th ed. Washington, DC, USA: American Public Health Association (APHA)

|

| [2] |

Armstrong D A, Chippendale D, Knight A W, et al. 1978. Interaction of ionized and un-ionized ammonia on short-term survival and growth of prawn larvae, Macrobrachium rosenbergh. The Biological Bulletin, 154(1): 15–31. doi: 10.2307/1540771

|

| [3] |

Atanassov C L, Muller C D, Sarhan S, et al. 1994. Effect of ammonia on endocytosis, cytokine production and lysosomal enzyme activity of a microglial cell line. Research in Immunology, 145(4): 277–288. doi: 10.1016/S0923-2494(94)80016-2

|

| [4] |

Auch A F, Klenk H P, Göker M. 2010a. Standard operating procedure for calculating genome-to-genome distances based on high-scoring segment pairs. Standards in Genomic Sciences, 2(1): 142–148. doi: 10.4056/sigs.541628

|

| [5] |

Auch A F, Von Jan M, Klenk H P, et al. 2010b. Digital DNA-DNA hybridization for microbial species delineation by means of genome-to-genome sequence comparison. Standards in Genomic Sciences, 2(1): 117–134. doi: 10.4056/sigs.531120

|

| [6] |

Carrera J, Vicent T, Lafuente F J. 2003. Influence of temperature on denitrification of an industrial high-strength nitrogen wastewater in a two-sludge system. Water SA, 29(1): 11–16

|

| [7] |

Chen Qian, Ni Jinren. 2012. Ammonium removal by Agrobacterium sp. LAD9 capable of heterotrophic nitrification–aerobic denitrification. Journal of Bioscience and Bioengineering, 113(5): 619–623. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiosc.2011.12.012

|

| [8] |

Chin C S, Alexander D H, Marks P, et al. 2013. Nonhybrid, finished microbial genome assemblies from long-read SMRT sequencing data. Nature Methods, 10(6): 563–569. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2474

|

| [9] |

Chiu Y C, Lee L L, Chang Chengnan, et al. 2007. Control of carbon and ammonium ratio for simultaneous nitrification and denitrification in a sequencing batch bioreactor. International Biodeterioration & Biodegradation, 59(1): 1–7

|

| [10] |

Gardner P R, Gardner A M, Martin L A, et al. 1998. Nitric oxide dioxygenase: an enzymic function for flavohemoglobin. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 95(18): 10378–10383. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.18.10378

|

| [11] |

Goris J, Konstantinidis K T, Klappenbach J A, et al. 2007. DNA–DNA hybridization values and their relationship to whole-genome sequence similarities. International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology, 57(1): 81–91. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.64483-0

|

| [12] |

He Tengxia, Li Zhenlun, Sun Quan, et al. 2016. Heterotrophic nitrification and aerobic denitrification by Pseudomonas tolaasii Y-11 without nitrite accumulation during nitrogen conversion. Bioresource Technology, 200: 493–499. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2015.10.064

|

| [13] |

He Tengxia, Xie Deti, Li Zhenlun, et al. 2017. Ammonium stimulates nitrate reduction during simultaneous nitrification and denitrification process by Arthrobacter arilaitensis Y-10. Bioresource Technology, 239: 66–73. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2017.04.125

|

| [14] |

Hooper A B, Vannelli T, Bergmann D J, et al. 1997. Enzymology of the oxidation of ammonia to nitrite by bacteria. Antonie van Leeuwenhoek, 71(1): 59–67

|

| [15] |

Huang Xiaofei, Li Weiguang, Zhang Duoying, et al. 2013. Ammonium removal by a novel oligotrophic Acinetobacter sp. Y16 capable of heterotrophic nitrification-aerobic denitrification at low temperature. Bioresource Technology, 146: 44–50. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2013.07.046

|

| [16] |

Hynes R K, Knowles R. 1978. Inhibition by acetylene of ammonia oxidation in Nitrosomonas europaea. FEMS Microbiology Letters, 4(6): 319–321. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1978.tb02889.x

|

| [17] |

Kan Fu, Xia Qinbin, Li Zhong, et al. 2011. Research of ammonia adsorption with Maifan stone. Industrial Safety and Environmental Protection, 37(4): 3–5

|

| [18] |

Kim J K, Park K J, Cho K S, et al. 2005. Aerobic nitrification–denitrification by heterotrophic Bacillus strains. Bioresource Technology, 96(17): 1897–1906. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2005.01.040

|

| [19] |

Koren S, Schatz M C, Walenz B P, et al. 2012. Hybrid error correction and de novo assembly of single-molecule sequencing reads. Nature Biotechnology, 30(7): 693–700. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2280

|

| [20] |

Krzywinski M, Schein J, Birol I, et al. 2009. Circos: an information aesthetic for comparative genomics. Genome Research, 19(9): 1639–1645. doi: 10.1101/gr.092759.109

|

| [21] |

Li Guizhen, Lai Qiliang, Yan Peisheng, et al. 2019. Roseovarius amoyensis sp. nov. and Muricauda amoyensis sp. nov., isolated from the Xiamen coast. International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology, 69(10): 3100–3108. doi: 10.1099/ijsem.0.003595

|

| [22] |

Lin Y C, Chen J C. 2003. Acute toxicity of nitrite on Litopenaeus vannamei (Boone) juveniles at different salinity levels. Aquaculture, 224(1–4): 193–201. doi: 10.1016/S0044-8486(03)00220-5

|

| [23] |

Lu Lu, Jia Zhongjun. 2013. Urease gene-containing Archaea dominate autotrophic ammonia oxidation in two acid soils. Environmental Microbiology, 15(6): 1795–1809. doi: 10.1111/1462-2920.12071

|

| [24] |

Lundberg J O, Weitzberg E, Cole J A, et al. 2004. Nitrate, bacteria and human health. Nature Reviews Microbiology, 2(7): 593–602. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro929

|

| [25] |

McCarty G W. 1999. Modes of action of nitrification inhibitors. Biology and Fertility of Soils, 29(1): 1–9. doi: 10.1007/s003740050518

|

| [26] |

Meier-Kolthoff J P, Auch A F, Klenk H P, et al. 2013. Genome sequence-based species delimitation with confidence intervals and improved distance functions. BMC Bioinformatics, 14: 60. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-14-60

|

| [27] |

Myers R H, Montgomery D C, Anderson-Cook C M. 2016. Response Surface Methodology: Process and Product Optimization Using Designed Experiments. New York: John Wiley & Sons

|

| [28] |

Qu Dan, Wang Cong, Wang Yanfang, et al. 2015. Heterotrophic nitrification and aerobic denitrification by a novel groundwater origin cold-adapted bacterium at low temperatures. RSC Advances, 5(7): 5149–5157. doi: 10.1039/C4RA13141J

|

| [29] |

Qu Jianhua, Meng Xianlin, You Hong, et al. 2017. Utilization of rice husks functionalized with xanthates as cost-effective biosorbents for optimal Cd(II) removal from aqueous solution via response surface methodology. Bioresource Technology, 241: 1036–1042. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2017.06.055

|

| [30] |

Ren Yongxiang, Yang Lei, Liang Xian. 2014. The characteristics of a novel heterotrophic nitrifying and aerobic denitrifying bacterium, Acinetobacter junii YB. Bioresource Technology, 171: 1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2014.08.058

|

| [31] |

Richter M, Rosselló-Móra R. 2009. Shifting the genomic gold standard for the prokaryotic species definition. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 106(45): 19126–19131. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0906412106

|

| [32] |

Rodriguez-Caballero A, Hallin S, Påhlson C, et al. 2012. Ammonia oxidizing bacterial community composition and process performance in wastewater treatment plants under low temperature conditions. Water Science and Technology, 65(2): 197–204. doi: 10.2166/wst.2012.643

|

| [33] |

Ryden J C, Skinner J H, Nixon D J. 1987. Soil core incubation system for the field measurement of denitrification using acetylene-inhibition. Soil Biology and Biochemistry, 19(6): 753–757. doi: 10.1016/0038-0717(87)90059-9

|

| [34] |

Savasari M, Emadi M, Ali Bahmanyar M, et al. 2015. Optimization of Cd (II) removal from aqueous solution by ascorbic acid-stabilized zero valent iron nanoparticles using response surface methodology. Journal of Industrial and Engineering Chemistry, 21: 1403–1409. doi: 10.1016/j.jiec.2014.06.014

|

| [35] |

Schopfer M P, Mondal B, Lee D H, et al. 2009. Heme/O2/·NO Nitric oxide dioxygenase (NOD) reactivity: phenolic nitration via a putative heme-peroxynitrite intermediate. Journal of the American Chemical Society, 131(32): 11304–11305. doi: 10.1021/ja904832j

|

| [36] |

Schuler D J, Boardman G D, Kuhn D D, et al. 2010. Acute toxicity of ammonia and nitrite to pacific white shrimp, Litopenaeus vannamei, at low salinities. Journal of the World Aquaculture Society, 41(3): 438–446. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-7345.2010.00385.x

|

| [37] |

Shan H, Obbard J. 2001. Ammonia removal from prawn aquaculture water using immobilized nitrifying bacteria. Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology, 57(5−6): 791–798. doi: 10.1007/s00253-001-0835-1

|

| [38] |

Smart G R. 1978. Investigations of the toxic mechanisms of ammonia to fish–gas exchange in rainbow trout (Salmo gairdneri) exposed to acutely lethal concentrations. Journal of Fish Biology, 12(1): 93–104. doi: 10.1111/j.1095-8649.1978.tb04155.x

|

| [39] |

Tatusova T, Dicuccio M, Badretdin A, et al. 2016. NCBI prokaryotic genome annotation pipeline. Nucleic Acids Research, 44(14): 6614–6624. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw569

|

| [40] |

Thurston R V, Russo R C, Vinogradov G A. 1981. Ammonia toxicity to fishes. Effect of pH on the toxicity of the unionized ammonia species. Environmental Science & Technology, 15(7): 837–840

|

| [41] |

Wang Te, Jiang Zhengzhong, Dong Wenbo, et al. 2019. Growth and nitrogen removal characteristics of Halomonas sp. B01 under high salinity. Annals of Microbiology, 69(13): 1425–1433. doi: 10.1007/s13213-019-01526-y

|

| [42] |

Wayne L G, Brenner D J, Colwell R R, et al. 1987. Report of the ad hoc committee on reconciliation of approaches to bacterial systematics. International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology, 37(4): 463–464. doi: 10.1099/00207713-37-4-463

|

| [43] |

Wei Yunxia, Li Yanfeng, Ye Zhengfang. 2010. Enhancement of removal efficiency of ammonia nitrogen in sequencing batch reactor using natural zeolite. Environmental Earth Sciences, 60(7): 1407–1413. doi: 10.1007/s12665-009-0276-1

|

| [44] |

Xu Yi, He Tengxia, Li Zhenlun, et al. 2017. Nitrogen removal characteristics of Pseudomonas putida Y-9 capable of heterotrophic nitrification and aerobic denitrification at low temperature. BioMed Research International, 2017: 1429018

|

| [45] |

Yao Shuo, Ni Jinren, Ma Tao, et al. 2013. Heterotrophic nitrification and aerobic denitrification at low temperature by a newly isolated bacterium, Acinetobacter sp. HA2. Bioresource Technology, 139: 80–86. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2013.03.189

|

| [46] |

Yu Lei, Wang Yangqing, Liu Hongjie, et al. 2016. A novel heterotrophic nitrifying and aerobic denitrifying bacterium, Zobellella taiwanensis DN-7, can remove high-strength ammonium. Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology, 100(9): 4219–4229. doi: 10.1007/s00253-016-7290-5

|

| [47] |

Zerbino D R. 2010. Using the Velvet de novo assembler for short-read sequencing technologies. Current Protocols in Bioinformatics, 31(1): 5–11

|

| [48] |

Zhang Yan, Cheng Yu, Fei Yutao, et al. 2016. Response to different nitrogen forms of heterotrophic nitrifying-aerobic denitrifying bacteria X3. Advances in Marine Sciences, 3(4): 118–126. doi: 10.12677/AMS.2016.34016

|

| [49] |

Zhang Duoying, Li Weiguang, Huang Xiaofei, et al. 2013. Removal of ammonium in surface water at low temperature by a newly isolated Microbacterium sp. strain SFA13. Bioresource Technology, 137: 147–152. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2013.03.094

|

| [50] |

Zhang Jinbo, Sun Weijun, Zhong Wenhui, et al. 2014. The substrate is an important factor in controlling the significance of heterotrophic nitrification in acidic forest soils. Soil Biology and Biochemistry, 76: 143–148. doi: 10.1016/j.soilbio.2014.05.001

|

| [51] |

Zhang Jibin, Wu Pengxia, Hao Bo, et al. 2011. Heterotrophic nitrification and aerobic denitrification by the bacterium Pseudomonas stutzeri YZN-001. Bioresource Technology, 102(21): 9866–9869. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2011.07.118

|

| [52] |

Zhao Bin, An Qiang, He Yiliang, et al. 2012. N2O and N2 production during heterotrophic nitrification by Alcaligenes faecalis strain NR. Bioresource Technology, 116: 379–385. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2012.03.113

|

| [53] |

Zhao Bin, He Yiliang, Huang Jue, et al. 2010b. Heterotrophic nitrogen removal by Providencia rettgeri strain YL. Journal of Industrial Microbiology & Biotechnology, 37(6): 609–616

|

| [54] |

Zhao Bin, He Yiliang, Hughes J, et al. 2010a. Heterotrophic nitrogen removal by a newly isolated Acinetobacter calcoaceticus HNR. Bioresource Technology, 101(14): 5194–5200. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2010.02.043

|

| [55] |

Zhou Xiang, Xin Zhijun, Lu Xihong, et al. 2013. High efficiency degradation crude oil by a novel mutant irradiated from Dietzia strain by 12C6+ heavy ion using response surface methodology. Bioresource Technology, 137: 386–393. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2013.03.097

|

| [56] |

Zhu Guibing, Peng Yongzhen, Li Baikun, et al. 2008. Biological removal of nitrogen from wastewater. In: Whitacre D M, ed. Reviews of Environmental Contamination and Toxicology. New York: Springer, 192: 159–195

|

40-9-Li Guizhen Supplementary information Table S1 (1).pdf

40-9-Li Guizhen Supplementary information Table S1 (1).pdf

|

|

| 1. | Zhao Chen, Jian Li, Qianqian Zhai, et al. Nitrogen cycling process and application in different prawn culture modes. Reviews in Aquaculture, 2024, 16(4): 1580. doi:10.1111/raq.12912 | |

| 2. | Ling Wang, You-Wei Cui. Mutualistic symbiosis of fungi and nitrogen-fixing bacteria in halophilic aerobic granular sludge treating nitrogen-deficient hypersaline organic wastewater. Bioresource Technology, 2024, 394: 130183. doi:10.1016/j.biortech.2023.130183 | |

| 3. | Elizaveta P. Pulikova, Andrey V. Gorovtsov, Yakov Kuzyakov, et al. Heterotrophic nitrification in soils: approaches and mechanisms. Soil Biology and Biochemistry, 2024. doi:10.1016/j.soilbio.2024.109706 | |

| 4. | Keke Lei, Zhaohua Wang, Shen Ma, et al. Construction of suspended bagasse bioflocs and evaluation of their effectiveness in shrimp (Penaeus vannamei) aquaculture systems. Aquaculture, 2024, 586: 740826. doi:10.1016/j.aquaculture.2024.740826 | |

| 5. | Rohini Mattoo, Suman B M. Microbial roles in the terrestrial and aquatic nitrogen cycle—implications in climate change. FEMS Microbiology Letters, 2023, 370 doi:10.1093/femsle/fnad061 | |

| 6. | Yumeng Xie, Xiangli Tian, Yu He, et al. Nitrogen removal capability and mechanism of a novel heterotrophic nitrification–aerobic denitrification bacterium Halomonas sp. DN3. Bioresource Technology, 2023, 387: 129569. doi:10.1016/j.biortech.2023.129569 | |

| 7. | Guizhen Li, Mengjiao Wei, Guangshan Wei, et al. Efficient heterotrophic nitrification by a novel bacterium Sneathiella aquimaris 216LB-ZA1-12T isolated from aquaculture seawater. Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety, 2023, 266: 115588. doi:10.1016/j.ecoenv.2023.115588 | |

| 8. | Yuchen Yuan, Jiadong Liu, Bo Gao, et al. The Effect of Activated Sludge Treatment and Catalytic Ozonation on High Concentration of Ammonia Nitrogen Removal from Landfill Leachate. SSRN Electronic Journal, 2022. doi:10.2139/ssrn.4151696 | |

| 9. | Yuchen Yuan, Jiadong Liu, Bo Gao, et al. The effect of activated sludge treatment and catalytic ozonation on high concentration of ammonia nitrogen removal from landfill leachate. Bioresource Technology, 2022, 361: 127668. doi:10.1016/j.biortech.2022.127668 | |

| 10. | Yiming Yan, Hongwei Lu, Jin Zhang, et al. Simultaneous heterotrophic nitrification and aerobic denitrification (SND) for nitrogen removal: A review and future perspectives. Environmental Advances, 2022, 9: 100254. doi:10.1016/j.envadv.2022.100254 |

| Factor | Name | Level | Low level | High level |

| A | C/N concentration ratio | 4.0 | 2.0 | 6.0 |

| B | pH | 7.5 | 6.0 | 9.0 |

| C | NaCl/% | 2.5 | 0.0 | 5.0 |

| D | temperature/°C | 10.0 | 5.0 | 15.0 |

| Independent variables | Response | |||||

| Run | A | B | C | D | Ammonia removal Y1/% | |

| C/N concentration ratio | pH | NaCl/% | Temperature /°C | |||

| 1 | 2 | 6 | 2.5 | 10 | 40.3 | |

| 2 | 6 | 6 | 2.5 | 10 | 62.5 | |

| 3 | 2 | 9 | 2.5 | 10 | 52.4 | |

| 4 | 6 | 9 | 2.5 | 10 | 100.0 | |

| 5 | 4 | 7.5 | 0 | 5 | 68.0 | |

| 6 | 4 | 7.5 | 5 | 5 | 36.2 | |

| 7 | 4 | 7.5 | 0 | 15 | 70.3 | |

| 8 | 4 | 7.5 | 5 | 15 | 68.0 | |

| 9 | 2 | 7.5 | 2.5 | 5 | 36.0 | |

| 10 | 6 | 7.5 | 2.5 | 5 | 50.1 | |

| 11 | 2 | 7.5 | 2.5 | 15 | 37.5 | |

| 12 | 6 | 7.5 | 2.5 | 15 | 83.9 | |

| 13 | 4 | 6 | 0 | 10 | 59.8 | |

| 14 | 4 | 9 | 0 | 10 | 84.4 | |

| 15 | 4 | 6 | 5 | 10 | 54.9 | |

| 16 | 4 | 9 | 5 | 10 | 77.7 | |

| 17 | 2 | 7.5 | 0 | 10 | 51.0 | |

| 18 | 6 | 7.5 | 0 | 10 | 87.7 | |

| 19 | 2 | 7.5 | 5 | 10 | 43.1 | |

| 20 | 6 | 7.5 | 5 | 10 | 82.4 | |

| 21 | 4 | 6 | 2.5 | 5 | 18.5 | |

| 22 | 4 | 9 | 2.5 | 5 | 59.3 | |

| 23 | 4 | 6 | 2.5 | 15 | 40.0 | |

| 24 | 4 | 9 | 2.5 | 15 | 74.2 | |

| 25 | 4 | 7.5 | 2.5 | 10 | 67.0 | |

| 26 | 4 | 7.5 | 2.5 | 10 | 67.0 | |

| 27 | 4 | 7.5 | 2.5 | 10 | 67.0 | |

| 28 | 4 | 7.5 | 2.5 | 10 | 67.0 | |

| 29 | 4 | 7.5 | 2.5 | 10 | 67.0 | |

| Items | Description |

| General features | |

| Classification | domains: Bacteria, phylum: Proteobacteria, class: Gammaproteobacteria, order: Oceanospirillales, family: Halomonadaceae, genus: Halomonas, species: Halomonas venusta |

| Gram stain | negative |

| Cell shape | rod |

| Motility | motile |

| Pigmentation | no-pigment |

| Temperature range/°C | 4−55 |

| Optimum temperature/°C | 28−37 |

| Energy source | chemoorganotrophic |

| Terminal electron receptor | oxygen |

| Oxygen | aerobic |

| NaCl content/% | 0−15 |

| pH | 5.0−10.0 |

| MIGS data | |

| Submitted to INSDC | GenBank (ID: CP034367) |

| Investigation type | bacteria |

| Project name | Halomonas venusta strain: MA-ZP17-13 genome sequencing |

| Geographic location (country) | China |

| Collection date | 2018 |

| Environment (biome) | seawater farms |

| Environment (feature) | water |

| Environment (material) | seawater |

| Environmental package | mariculture samples from Zhangzhou, China |

| Biotic relationship | free-living |

| Pathogenicity | none |

| Sequencing method | PacBio RS, Illumina Hiseq2000 |

| Assembly | GS De Novo Assembler package |

| Finishing strategy | complete |

| Note: INSDC represents International Nucleotide Sequence Database Collaboration. | |

| Source | Sum of squares | Degree of freedom | Mean square | F-value | P |

| Model | 9 366.15 | 14 | 669.01 | 27.57 | < 0.000 1 |

| A (C/N concentration ratio) | 3 546.64 | 1 | 3 546.64 | 146.17 | < 0.000 1 |

| B (pH) | 2 465.33 | 1 | 2 465.33 | 101.61 | < 0.000 1 |

| C (NaCl) | 289.10 | 1 | 289.10 | 11.92 | 0.003 9 |

| D (temperature) | 932.80 | 1 | 932.80 | 38.45 | < 0.000 1 |

| AB | 161.29 | 1 | 161.29 | 6.65 | 0.021 9 |

| AC | 1.69 | 1 | 1.69 | 0.07 | 0.795 7 |

| AD | 260.82 | 1 | 260.82 | 10.75 | 0.005 5 |

| BC | 0.81 | 1 | 0.81 | 0.03 | 0.857 6 |

| BD | 10.89 | 1 | 10.89 | 0.45 | 0.513 8 |

| CD | 217.56 | 1 | 217.56 | 8.97 | 0.009 7 |

| A2 | 42.59 | 1 | 42.59 | 1.76 | 0.206 4 |

| B2 | 55.50 | 1 | 55.50 | 2.29 | 0.152 7 |

| C2 | 132.08 | 1 | 132.08 | 5.44 | 0.035 1 |

| D2 | 1 125.93 | 1 | 1 125.93 | 46.40 | < 0.000 1 |

| Residual | 339.68 | 14 | 24.26 | − | − |

| Note: −, no data. | |||||

| Strain name | Source | Salinity | Temperature/°C | RTAM/(mg·L−1·h−1) | Reference |

| Acinetobacter sp. HA2 | sediment | 0 | 10.0 | 3.03 | Yao et al. (2013) |

| Acinetobacter sp. Y16 | water | 0.12 | 2.0 | 0.092 | Huang et al. (2013) |

| Pseudomonas migulae AN-1 | water | 0 | 10.0 | 1.56 | Qu et al. (2015) |

| Pseudomonas putida Y-9 | soil | 0 | 15.0 | 2.85 | Xu et al. (2017) |

| H. venusta MA-ZP17-13 | seawater | 23.3 | 11.2 | 1.37 | present study |

| Note: RTAM represents removal rate of total ammonia nitrogen. | |||||

| Attribute | Genome (total) value | Proportion of total/% |

| Genome size/bp | 4 446 698 | 100.00 |

| G+C content/bp | 2 347 412 | 52.79 |

| Coding region/bp | 3 979 236 | 89.49 |

| TandemRepeat/bp | 60 444 | 1.52 |

| Total genes | 4 330 | 100.00 |

| RNA genes | 79 | 1.82 |

| rRNA operons | 18 | 0.42 |

| tRNA genes | 61 | 1.41 |

| Protein-coding genes | 4 251 | 98.18 |

| Genes assigned to COGs | 3 676 | 86.47 |

| Factor | Name | Level | Low level | High level |

| A | C/N concentration ratio | 4.0 | 2.0 | 6.0 |

| B | pH | 7.5 | 6.0 | 9.0 |

| C | NaCl/% | 2.5 | 0.0 | 5.0 |

| D | temperature/°C | 10.0 | 5.0 | 15.0 |

| Independent variables | Response | |||||

| Run | A | B | C | D | Ammonia removal Y1/% | |

| C/N concentration ratio | pH | NaCl/% | Temperature /°C | |||

| 1 | 2 | 6 | 2.5 | 10 | 40.3 | |

| 2 | 6 | 6 | 2.5 | 10 | 62.5 | |

| 3 | 2 | 9 | 2.5 | 10 | 52.4 | |

| 4 | 6 | 9 | 2.5 | 10 | 100.0 | |

| 5 | 4 | 7.5 | 0 | 5 | 68.0 | |

| 6 | 4 | 7.5 | 5 | 5 | 36.2 | |

| 7 | 4 | 7.5 | 0 | 15 | 70.3 | |

| 8 | 4 | 7.5 | 5 | 15 | 68.0 | |

| 9 | 2 | 7.5 | 2.5 | 5 | 36.0 | |

| 10 | 6 | 7.5 | 2.5 | 5 | 50.1 | |

| 11 | 2 | 7.5 | 2.5 | 15 | 37.5 | |

| 12 | 6 | 7.5 | 2.5 | 15 | 83.9 | |

| 13 | 4 | 6 | 0 | 10 | 59.8 | |

| 14 | 4 | 9 | 0 | 10 | 84.4 | |

| 15 | 4 | 6 | 5 | 10 | 54.9 | |

| 16 | 4 | 9 | 5 | 10 | 77.7 | |

| 17 | 2 | 7.5 | 0 | 10 | 51.0 | |

| 18 | 6 | 7.5 | 0 | 10 | 87.7 | |

| 19 | 2 | 7.5 | 5 | 10 | 43.1 | |

| 20 | 6 | 7.5 | 5 | 10 | 82.4 | |

| 21 | 4 | 6 | 2.5 | 5 | 18.5 | |

| 22 | 4 | 9 | 2.5 | 5 | 59.3 | |

| 23 | 4 | 6 | 2.5 | 15 | 40.0 | |

| 24 | 4 | 9 | 2.5 | 15 | 74.2 | |

| 25 | 4 | 7.5 | 2.5 | 10 | 67.0 | |

| 26 | 4 | 7.5 | 2.5 | 10 | 67.0 | |

| 27 | 4 | 7.5 | 2.5 | 10 | 67.0 | |

| 28 | 4 | 7.5 | 2.5 | 10 | 67.0 | |

| 29 | 4 | 7.5 | 2.5 | 10 | 67.0 | |

| Items | Description |

| General features | |

| Classification | domains: Bacteria, phylum: Proteobacteria, class: Gammaproteobacteria, order: Oceanospirillales, family: Halomonadaceae, genus: Halomonas, species: Halomonas venusta |

| Gram stain | negative |

| Cell shape | rod |

| Motility | motile |

| Pigmentation | no-pigment |

| Temperature range/°C | 4−55 |

| Optimum temperature/°C | 28−37 |

| Energy source | chemoorganotrophic |

| Terminal electron receptor | oxygen |

| Oxygen | aerobic |

| NaCl content/% | 0−15 |

| pH | 5.0−10.0 |

| MIGS data | |

| Submitted to INSDC | GenBank (ID: CP034367) |

| Investigation type | bacteria |

| Project name | Halomonas venusta strain: MA-ZP17-13 genome sequencing |

| Geographic location (country) | China |

| Collection date | 2018 |

| Environment (biome) | seawater farms |

| Environment (feature) | water |

| Environment (material) | seawater |

| Environmental package | mariculture samples from Zhangzhou, China |

| Biotic relationship | free-living |

| Pathogenicity | none |

| Sequencing method | PacBio RS, Illumina Hiseq2000 |

| Assembly | GS De Novo Assembler package |

| Finishing strategy | complete |

| Note: INSDC represents International Nucleotide Sequence Database Collaboration. | |

| Source | Sum of squares | Degree of freedom | Mean square | F-value | P |

| Model | 9 366.15 | 14 | 669.01 | 27.57 | < 0.000 1 |

| A (C/N concentration ratio) | 3 546.64 | 1 | 3 546.64 | 146.17 | < 0.000 1 |

| B (pH) | 2 465.33 | 1 | 2 465.33 | 101.61 | < 0.000 1 |

| C (NaCl) | 289.10 | 1 | 289.10 | 11.92 | 0.003 9 |

| D (temperature) | 932.80 | 1 | 932.80 | 38.45 | < 0.000 1 |

| AB | 161.29 | 1 | 161.29 | 6.65 | 0.021 9 |

| AC | 1.69 | 1 | 1.69 | 0.07 | 0.795 7 |

| AD | 260.82 | 1 | 260.82 | 10.75 | 0.005 5 |

| BC | 0.81 | 1 | 0.81 | 0.03 | 0.857 6 |

| BD | 10.89 | 1 | 10.89 | 0.45 | 0.513 8 |

| CD | 217.56 | 1 | 217.56 | 8.97 | 0.009 7 |

| A2 | 42.59 | 1 | 42.59 | 1.76 | 0.206 4 |

| B2 | 55.50 | 1 | 55.50 | 2.29 | 0.152 7 |

| C2 | 132.08 | 1 | 132.08 | 5.44 | 0.035 1 |

| D2 | 1 125.93 | 1 | 1 125.93 | 46.40 | < 0.000 1 |

| Residual | 339.68 | 14 | 24.26 | − | − |

| Note: −, no data. | |||||

| Strain name | Source | Salinity | Temperature/°C | RTAM/(mg·L−1·h−1) | Reference |

| Acinetobacter sp. HA2 | sediment | 0 | 10.0 | 3.03 | Yao et al. (2013) |

| Acinetobacter sp. Y16 | water | 0.12 | 2.0 | 0.092 | Huang et al. (2013) |

| Pseudomonas migulae AN-1 | water | 0 | 10.0 | 1.56 | Qu et al. (2015) |

| Pseudomonas putida Y-9 | soil | 0 | 15.0 | 2.85 | Xu et al. (2017) |

| H. venusta MA-ZP17-13 | seawater | 23.3 | 11.2 | 1.37 | present study |

| Note: RTAM represents removal rate of total ammonia nitrogen. | |||||

| Attribute | Genome (total) value | Proportion of total/% |

| Genome size/bp | 4 446 698 | 100.00 |

| G+C content/bp | 2 347 412 | 52.79 |

| Coding region/bp | 3 979 236 | 89.49 |

| TandemRepeat/bp | 60 444 | 1.52 |

| Total genes | 4 330 | 100.00 |

| RNA genes | 79 | 1.82 |

| rRNA operons | 18 | 0.42 |

| tRNA genes | 61 | 1.41 |

| Protein-coding genes | 4 251 | 98.18 |

| Genes assigned to COGs | 3 676 | 86.47 |