| Citation: | Ruili Sun, Peiliang Li, Yanzhen Gu, Chaojie Zhou, Cong Liu, Lin Zhang. Seasonal variation of the shape and location of the Luzon cold eddy[J]. Acta Oceanologica Sinica, 2023, 42(5): 14-24. doi: 10.1007/s13131-022-2084-3 |

The South China Sea (SCS) is the largest semi-closed marginal sea in the Northwest Pacific (NWP). To the north, west, and south it is surrounded by continents and islands, while to the east it is separated from the NWP by Taiwan Island and the Philippines Islands (Fig. 1). The SCS is situated in the East Asian monsoon regime, and its large-scale ocean circulation is mainly controlled by monsoon (Chu et al., 1999; Hwang and Chen, 2000; Qu, 2000; Liu et al., 2004). In summer, prevailing southwest monsoon cause cyclonic (anticyclonic) circulation in the north (south) of the SCS; in winter, prevailing northeast monsoon cause cyclonic circulation in the whole SCS basin. In addition to the East Asian monsoon, the ocean circulation in the SCS is also affected by the intrusion of the Kuroshio through the Luzon Strait (LS) (Jia and Liu, 2004; Zhang et al., 2017). The Kuroshio can invade the SCS in the form of “Leak”, “Loop”, and so on, and can significantly affect the temperature-salt structure and ocean circulation in the north of the SCS (Caruso et al., 2006; Nan et al., 2011, 2015; Zhang et al., 2017).

The LS, located between the Luzon Island and Taiwan Island, is an important gap for energy and particle between the SCS and NWP (Nan et al., 2015; Sun et al., 2022). Affected by topography, monsoon and the Kuroshio, the dynamics process in the LS is extremely complex. Due to the special geographical topography of the LS, the monsoon and Kuroshio will interact with the topography, resulting in obvious local ocean phenomena (Qu, 2000; Wang et al., 2008; Sun et al., 2016a, b). The Luzon cold eddy (LCE) is one of the important local ocean phenomena northwest of the Luzon Island, and was first recorded in Nitani (1970). It occurs northwest of Luzon Island in boreal winter (Fig. 1), first appears in late autumn, peaks from December–January, and decays in early spring (Qu, 2000). Its intensity increases and then decreases from late autumn to early spring, and the maximum occurs between December and January (Qu, 2000; Wang et al., 2012). The LCE strengthens (weakens) during La Niña (El Niño) years (Zheng et al., 2007; Sun et al., 2015; He et al., 2016; Deng et al., 2022). Blocked by Luzon Island, the northeast monsoon produces positive wind stress curl in the northwest of Luzon Island, which then leads to the generation of the LCE (Wang et al., 2008; Sun et al., 2015).

LCE contributes to the complex dynamic environment and plays an important role in marine ecosystem in the SCS. LCE contributes to upwelling and then is beneficial to winter blooms of primary production (Shaw et al., 1996; Tang et al., 1999; Wang et al., 2010; Lu et al., 2015). Due to ocean advection of the LCE, the cold (warm) water is located in its northwest (southeast) part, forming a thermal front northwest of Luzon Island (Belkin and Cornillon, 2003; Wang et al., 2012; Sun et al., 2015). At the same time, the LCE is a quasi-stable and excellent object to study the characteristics of mesoscale eddy (Wang et al., 2012). Therefore, full understandings of the LCE are valuable for understanding the dynamics process and mesoscale eddies of the SCS.

Although a substantial amount of research on the LCE exist, we re-examined the LCE because of its importance, and found that seasonal variation of the shape and location of the LCE were significant and had an important impact on the marine environment such as spatial distribution of thermal front and chlorophyll a (Fig. 2). Previous studies mainly studied the statistical characteristics, formation mechanism and impact on the marine environment of the LCE in the climatological state (Wang et al., 2003, 2008, 2012; Sun et al., 2015). The study of seasonal variation is less probed. Although Sun and Liu (2011) pointed out that the LCE had a double eddy structure and studied the intraseasonal variation of geostrophic vorticity of the LCE structure northwest of the Luzon Island, seasonal variations of the other parameters such as shape and location of the LCE were not involved. To the best of our knowledge, it is unclear that seasonal variations of shape and location of the LCE. In order to systematically solve the question above, we will study the seasonal variations characteristic of shape and location of the LCE, its dynamic mechanism, and its impact on the marine environment in this paper. The rest of this paper is organized as follows: Section 2 briefly introduces the data and methods, Section 3 presents the research results, Section 4 provides a discussion, and Section 5 provides a conclusion.

Satellite-observed sea level anomaly (SLA) and geostrophic current were obtained from the Copernicus Marine Environment Monitoring Service (CMEMS). The dataset merged data from all altimeter missions including Sentinel-3A/B, HY-2A, Jason-3, Cryosat-2, Jason-1, TOpeX/Poseidon, OSTM/Jason-2, Envisat, GFO, and ERS-1/2. The datasets contain one near-real product and one delayed-time product which is used in this paper. The delayed-time datasets have been intercalibrated, providing high-precision and long-time series data from January 1, 1993, to August 2, 2021 (Pujol, 2022). The spatial and temporal resolution of the delayed-time datasets are 0.25°×0.25° and 1 day, respectively. The datasets contain aliases from coastal waves and tides signals on the shallow shelf, so we masked out the data for ocean regions with a water depth of fewer than 200 m.

Chlorophyll a concentration datasets were provided by the Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS) of the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA). They have a temporal resolution of 1 day and a spatial resolution of 0.25°×0.25°. The datasets are calculated using an empirical relationship derived from in situ measurements of chlorophyll a and remoting sensing reflectances in the blue-to-green region of the visible spectrum (Hu et al., 2012).

Cross-Calibrated Multi-Platform (CCMP) version 2.0 ocean vector wind datasets were from Remote Sensing Systems. The CCMP dataset merged satellite remote sensing observation data, in situ observation data, and model wind data using multiple analysis methods. It provides global coverage data from August 1987 to present, with a spatial resolution of 0.25°×0.25° and a temporal sampling frequency of 6 h (Atlas et al., 2011; Mears et al., 2019).

Optimum Interpolation Sea Surface Temperature (OISST) data were provided by National Centers for Environmental Information (NCEI). The dataset incorporates observations from different platforms: ships, buoys, satellites and Argo floats into a regular global grid. Interpolation was used to fill gaps on the grid. Ship and satellite observation data were referenced to buoy observation data to compensate for platform differences and sensor biases. The OISST dataset provides a global coverage from January 1, 1982 to present, with a spatial resolution of 0.25°×0.25° and a temporal sampling frequency of 1 day (Huang et al., 2021).

The LCE northwest of Luzon Island has complex spatiotemporal characteristics. In this study, in order to extract the representative spatial mode of the LCE, we introduced the self-organizing map (SOM) method. Based on unsupervised learning, SOM is an artificial neural network, and is an effective method for classification and feature extraction (Kohonen, 2001; Tsui and Wu, 2012). This method gathers similar features into a class and can also be regarded as a clustering method. It has been applied to many oceanographic studies and achieved good results (Liu et al., 2006; Liu and Weisberg, 2007; Tsui and Wu, 2012; Sun et al., 2016a, 2018; Gu et al., 2018; Lu et al., 2022).

The parameters such as lattice, training method, map shape, initialized weight and map size need to be specified before the training process of SOM. In this study, the tunable parameters were chosen based on the reference of Liu et al. (2006), which gave a practical process for choosing tunable parameters. The parameter of map size is obtained through tests according to actual situation of the LCE. In Fig. 2, the variation of the LCE is mainly manifested in the variation of shape and location, and the variation of shape and location are phase locked. The closer the shape of the LCE is to the circle, the farther north the location of the LCE is. Therefore, a map size of 1 × 2 was chosen in this study. A series of tests with different sizes such as 1 × 3, 2 × 2, and 2 × 3 were run, respectively. Although the patterns in the larger map size of the SOM provided more details about the LCE, the patterns of the LCE were very similar to the ones with the map size of 1 × 2.

Using minimum Euclidean distance for input data, SOM gives a best-matching unit (BMU), which records the category of each pattern of the LCE. A time series of BMU can reflect the evolution process of every pattern of the LCE and can be used to calculate the occurrence frequency of every pattern of the LCE.

Figure 3 is a schematic of a fitting ellipse for the LCE. The ellipticity of the LCE ellipse is defined as the ratio of the minor axis to the major axis of ellipse. The formula can be expressed as

The LCE is essentially a mesoscale eddy. Its particularity lies in its proximity to land and its quasi-stable state. We identify the LCE according to the following four criteria (Wang et al., 2003; Sun et al., 2016a): (1) the presence of closed SLA contours; (2) the center position of the LCE is over water deeper than 200 m; (3) the SLA difference between its center and its outermost contour is greater than 4×10−2 m (Roemmich and Gilson, 2001); and (4) the contour closest to land represents the edge of the LCE. The 3rd criterion was chosen because the satellite measurement error of the SLA is around 2×10−2–3×10−2 m (Ducet et al., 2000). The identification method of the LCE was applied in identifying the outermost edge and shape of the LCE.

Based on the gradient magnitude (GM) method, the calculation of GM is as follows (Chang et al., 2010; Sun et al., 2015):

| $$ {\rm{GM}}=\sqrt{{\left(-\frac{\partial T}{\partial x}\right)}^{2}{+\left(-\frac{\partial T}{\partial y}\right)}^{2}} , $$ | (1) |

where GM is the gradient magnitude of SST; T is the SST; and x, y are the conventional east-west and north-south Cartesian coordinates, respectively. We chose 0.1℃/(10 km) as the threshold of the thermal front because the 0.1℃/(10 km) contour is a good reflection of the shape variation of the thermal front northwest of Luzon Island. We ran a series of tests with different thresholds such as 0.09℃/(10 km), 0.11℃/(10 km), and 0.12℃/(10 km). Our conclusions in this study are consistent. The definition of the thermal front was used to characterize the spatial range and intensity of thermal front northwest of the Luzon Island.

Based on satellite-observed SLA data and the LCE identification method described in the Section 2.2.3 to identify the LCE, we found that the shape of the LCE changed from a flat ellipse to a circular ellipse from December to March (Fig. 2). Figure 4 gives the seasonal variation of the shape of the LCE. Figure 4a shows that the ellipticity of the LCE increases gradually from 0.16 to 0.82 as the shape of the LCE changes from a flat ellipse to a circular ellipse. Figure 4b shows that the included angle decreases from 38.4° to 34.1° during December–January, and then increases from 34.1° to 54.5° during January–March, which indicates that the LCE rotates clockwise in the development stage (December–January), and then rotates counterclockwise in the recession stage (January–March).

To extract more representative features of the seasonal variation of the LCE, we applied the SOM method to extract the temporal and spatial variation of the LCE. Figure 5 shows that the LCE has two main spatial structures. One is approximately elliptical (Fig. 5a) and the other is approximately circular (Fig. 5b). These are defined as the elliptical mode and the circular mode, respectively. Figure 6 shows that the elliptical (circular) mode of the LCE occurred mainly in December and January (February and March). This further verifies the seasonal variations in the shape of the LCE. The shape of the LCE was a flat (circular) ellipse in early winter (late winter and early spring).

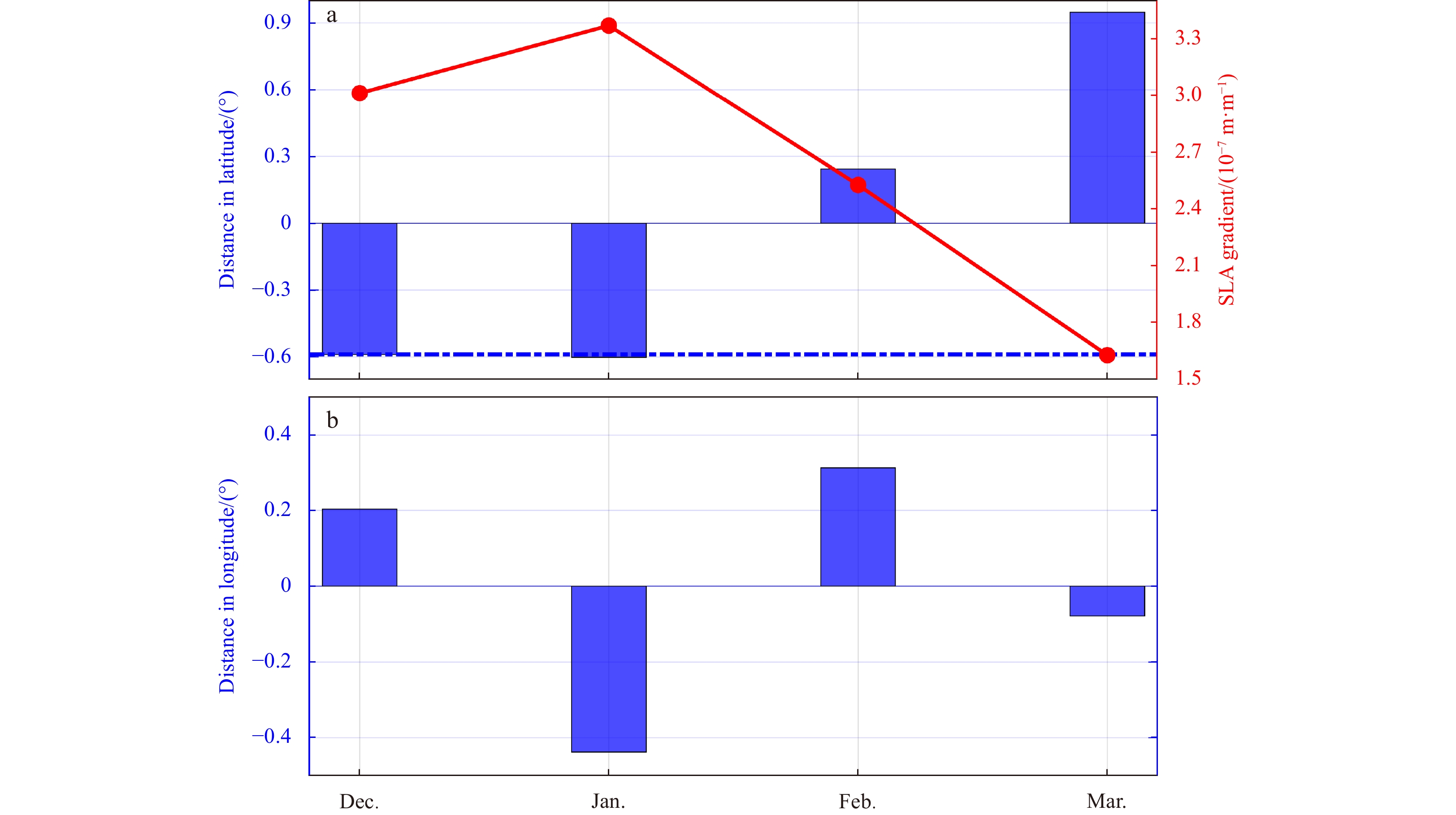

Based on satellite-observed SLA data and the LCE identification method described in the Section 2.2.3 to identify the LCE, we found that the center location of the LCE moves gradually north from December to March (Fig. 2). Figure 7 quantifies the seasonal variation of the location of the LCE. Figure 7a shows that the distance in latitude changes from −0.59° to −0.6° during December–January and changes from −0.6° to 1° during January–March, a difference of 1.6° latitude. The mean value of the latitude of the center location is 18°N, and the latitude of the LCE changes from 17.4°N to 19°N. Seasonal variation of the distance in longitude of the LCE shows no obvious pattern (Fig. 7b).

The center of the elliptical (circular) mode of the LCE extracted by the SOM method was relatively south (north), and was located in 16.9°N, 118.1°E (18.4°N, 118.4°E) (Fig. 5), and the elliptical (circular) mode mainly occurred in December and January (February and March). This further verifies the seasonal variations in the location of the LCE. The center location of the LCE was relatively south (north) in early winter (late winter and early spring).

The formation of the LCE is related to the topographic wind stress curl northwest of Luzon Island, which also is one of main ocean dynamic processes northwest of Luzon Island (Qu, 2000; Wang et al., 2008). Therefore, we discussed the role of topographic wind stress curl northwest of Luzon Island in the seasonal variations of the LCE shape. Figure 4a shows that the shape of the LCE changes from a flat ellipse to a circular ellipse from December to March, and shows that the intensity of the wind stress curl northwest of Luzon Island weakens from December to March. There is a good correspondence between the shape of the LCE and the intensity of the wind stress curl. We inferred that the variation of the LCE shape was caused by the variation of the wind stress curl intensity. The smaller the intensity of wind stress curl northwest of Luzon Island, the closer the shape of the LCE is to the circle.

In order to verify the hypothesis above, we introduced the following extremum method. Figure 8 shows that the location of the positive wind stress curl northwest of Luzon Island is almost unchanged from October to April. Therefore, we can use the time series of the wind stress curl surrounded by the solid black line in Fig. 8 as the intensity index of wind stress curl (Fig. 9a). We composited SLA based on the days when the positive and negative intensity index values are more than one standard deviation away from the mean. Figure 9b (Fig. 9c) shows that the LCE is approximately elliptic (circular) when the wind stress curl northwest of Luzon Island is strong (weak). The process can be described as follow. Under the force of wind stress curl, the initial shape of the LCE must be consistent with the spatial shape of the wind stress curl northwest of Luzon Island. The shape of the wind stress curl is a northeast to southwest ellipse, so the shape of the LCE is flat elliptical in December. With the weakening of the wind stress curl, the LCE is no longer bound by the wind stress curl and gradually return to a circular ellipse in March.

The movement of water body in the ocean is mainly related to the pressure gradient. Therefore, we discussed the pressure gradient in the seasonal variation of the LCE location. Figure 7a shows that the LCE moves south from December to January, and then moves north from January to March, and shows that gradient of SLA north of the SCS increases from December to January, and then decreases from January to March. There is a good correspondence between distance variation of the LCE in latitude and the gradient of SLA north of the SCS. We inferred that location variation of the LCE was caused by the variation of the gradient of SLA north of the SCS. The smaller the gradient of SLA north of the SCS, the more southward the location of the LCE.

Although the Kuroshio can invade the north of the SCS through the LS in winter, dynamic height of the SCS, especially at the LCE, is still mainly controlled by the northeast monsoon (Qu, 2000; Liu et al., 2004). Therefore, the SLA gradient north of the SCS as is shown in Fig. 2 is mainly controlled by northeast monsoon (Qu, 2000). The SLA gradient north of the SCS in Fig. 9a (Fig. 9b) is 3.01×10−7 m/m (2.02×10−7 m/m), and the latitude of the LCE location in the Fig. 9a (Fig. 9b) is 17.375°N (18.375°N), which verify the hypothesis that when the wind stress curl northwest of Luzon Island is strong (weak), the SLA gradient north of the SCS is strong (weak), the LCE moves south (north).

LCE is an important ocean dynamic processes northwest of Luzon Island, and inevitably has an impact on the marine environment. Previous studies have shown that the LCE can lead to the formation of ocean thermal fronts by geostrophic advection (Wang et al., 2012; Sun et al., 2015). At the same time, different shapes of the LCE produce different structures of geostrophic advection, spatial distribution of the thermal front northwest of Luzon Island should be related to the shape of the LCE. Figure 10 shows that from November to March, the shape of the thermal front changes from an ellipse to a semilunar arc, when the LCE gradually changes from a flat ellipse to a circular ellipse from December to March (Fig. 4). The closer the shape of the LCE is to a circle, the closer the shape of the thermal front is to a semilunar arc. Because the strength of the LCE is weakened in March, which leads to the weakening of the thermal front, we reduced the threshold of the thermal front to 0.09℃/(10 km) in March.

The spatial mode of the LCE extracted by SOM also can well verify the hypothesis above. Figures 11a and b give the spatial distribution of the thermal front corresponding to the elliptical mode and circular mode of the LCE, respectively, and shows that when the ellipticity of the LCE is small (big), the shape of the thermal front is close to an ellipse (a semilunar arc).

The chlorophyll a blooms northwest of Luzon Island in winter, and will be redistributed by the ocean current (Lu et al., 2015; Gao et al., 2021). Since different shapes of the LCE cause different structures of ocean current northwest of Luzon Island, a logical question is that how seasonal variation of the LCE shape affects the spatial distribution of chlorophyll a. Figure 12 shows that there is a good correspondence between spatial distribution of the chlorophyll a and geostrophic current caused by the LCE surrounded by the solid black line in Fig. 12. Chlorophyll a northwest of Luzon Island begins to appear in a circular distribution in November, develops into a northeast-southwest elliptical distribution in December and January, presents an east-west elliptical distribution in February, and then develops into a circular distribution in March, when the geostrophic current caused by the LCE is a northeast-southwest elliptical distribution in December and January, presents an east-west elliptical distribution in February, and weakens to a weak northward current northwest of Luzon Island.

Based on the above analysis, we inferred that seasonal variation of the LCE shape affect the spatial distribution by geostrophic advection. Figures 13a and b shows the spatial distribution of chlorophyll a corresponding to elliptical mode and circular modes of LCE, respectively. It shows that when the LCE is in the elliptical (circular) mode, the geostrophic current surrounded by the solid black line in Fig. 13a (Fig. 13b) is in a northeast-southwest (east-west) elliptical distribution, and the chlorophyll a is in a northeast-southwest (east-west) elliptical distribution northwest of Luzon Island, which verifies our hypothesis above. We will discuss the source of chlorophyll a in the Section 5.

Besides seasonal variation, LCE also has intraseasonal variation and interannual variation (Sun and Liu, 2011; Sun et al., 2015). Sun and Liu (2011) pointed out that the LCE had a double eddy structure, and that affected by the Kuroshio, the geostrophic vorticity of the LCE northwest of the Luzon Island had intraseasonal variation. However, the basic characteristics of intraseasonal variation of the LCE, such as radius, relative vorticity, moving speed, moving distance, etc., were still unclear. Sun et al. (2015) found that interannual variation of the LCE intensity was caused by the one of the wind stress curl northwest of Luzon Island. However, the interannual variation of other parameters, such as relative vorticity, radius, etc., were still unclear. Therefore, the research of intraseasonal and interannual variation of the LCE needs a lot of work and is worth further doing in the future.

Previous studies determined that the peak intensity of the LCE delays the peak intensity of the wind stress curl by one month (Wang et al., 2012). In this study, we found a real-time correspondence between the intensity of the wind stress curl and the shape of the LCE, and that there was no delay of one month. This did not seem contradictory. The shape of the LCE was embodied in changes in sea surface height. Sea surface height could change in real-time with the wind field. However, the intensity of the LCE was the final result of sea surface height variation, and it took about a month that the direct wind-forcing spins up a mesoscale eddy due to geostrophic adjustment (Liu et al., 2001; Wang et al., 2008).

We mentioned that the shape of the LCE can affect the spatial distribution of the chlorophyll a. One question was, where does the chlorophyll a come from? Previous studies have pointed out that the spatial distribution of the chlorophyll a in winter was related with upwelling caused by wind stress curl northwest of Luzon Island (Shaw et al., 1996; Tang et al., 1999; Udarbe-Walker and Villanoy, 2001; Liu et al., 2002; Martin and Villanoy, 2007; Wang et al., 2010; Lu et al., 2015). The northeast monsoon was blocked by Luzon Island, producing positive wind stress curl behind the Luzon Island. Ekman pumping caused by positive wind stress curl led to upwelling, which brought nutrients in the subsurface layer to the euphotic layer, and then led to the bloom of chlorophyll a.

We used observational data from multiple satellites to study seasonal variation in the shape and location of the LCE. The shape of the LCE had obvious seasonal variation. LCE showed a gradual transition from a flat ellipse to a circular ellipse when its ellipticity increased from 0.16 to 0.82 during December–March. Seasonal variation in the shape of the LCE was related to the intensity of the wind stress curl northwest of Luzon Island. The smaller the intensity of wind stress curl northwest of Luzon Island, the closer the shape of the LCE is to the circle.

The included angle decreased from 38.4° to 34.1° during December–January, and then increased from 34.1° to 54.5° during January–March. The location of the LCE also had seasonal variations. The LCE moved south from December to January and north from January to March. The maximum difference in latitude could reach 1.6°. Seasonal variation in the location of the LCE was caused by the pressure gradient between the south of Taiwan Island and the central location of the LCE. When the pressure gradient was large (small), LCE moved south (north).

Seasonal variation in the shape of the LCE could affect the spatial distribution of thermal front and chlorophyll a northwest of Luzon Island by geostrophic advection. A flat ellipse (a circular ellipse) shape of the LCE and its corresponding geostrophic advection caused the thermal front to be elliptical (semilunar arc) and chlorophyll a to distribute in a southwest-northeast (west-east) direction.

Acknowledgements: The authors would like to acknowledge several datasets used in this paper. Satellite observed sea surface level and geostrophic current are provided by CMEMS. Chlorophyll a concentration datasets are obtained by MODIS of NASA (|

Atlas R, Hoffman R N, Ardizzone J, et al. 2011. A cross-calibrated, multiplatform ocean surface wind velocity product for meteorological and oceanographic applications. Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society, 92(2): 157–174. doi: 10.1175/2010BAMS2946.1

|

|

Belkin I, Cornillon P. 2003. SST fronts of the Pacific coastal and marginal seas. Pacific Oceanography, 1(2): 90–113

|

|

Caruso M J, Gawarkiewicz G G, Beardsley R C. 2006. Interannual variability of the Kuroshio intrusion in the South China Sea. Journal of Oceanography, 62(4): 559–575. doi: 10.1007/s10872-006-0076-0

|

|

Chang Yi, Shieh Wei-Juan, Lee Ming-An, et al. 2010. Fine-scale sea surface temperature fronts in wintertime in the northern South China Sea. International Journal of Remote Sensing, 31(17–18): 4807–4818

|

|

Chu P C, Edmons N L, Fan Chenwu. 1999. Dynamical mechanisms for the South China Sea seasonal circulation and thermohaline variabilities. Journal of Physical Oceanography, 29(11): 2971–2989. doi: 10.1175/1520-0485(1999)029<2971:DMFTSC>2.0.CO;2

|

|

Deng Sijie, Xie Lingling, Zhu Zhenkun, et al. 2022. Interannual variation of the Luzon cold eddy and its mechanism. Advances in Marine Science (in Chinese), 40(1): 13–26

|

|

Ducet N, Le Traon P Y, Reverdin G. 2000. Global high-resolution mapping of ocean circulation from TOPEX/Poseidon and ERS-1 and -2. Journal of Geophysical Research, 105(C8): 19477–19498. doi: 10.1029/2000JC900063

|

|

Gao Hui, Zhao Hui, Han Guoqi, et al. 2021. Spatio-temporal variations of winter phytoplankton blooms northwest of the Luzon Island in the South China Sea. Frontiers in Marine Science, 8: 637499. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2021.637499

|

|

Gu Chao, Li Hong, Xu Fanghua, et al. 2018. Numerical study of Jiulongjiang river plume in the wet season 2015. Regional Studies in Marine Science, 24: 82–96. doi: 10.1016/j.rsma.2018.07.004

|

|

He Yinghui, Xie Jieshuo, Cai Shuqun. 2016. Interannual variability of winter eddy patterns in the eastern South China Sea. Geophysical Research Letters, 43(10): 5185–5193. doi: 10.1002/2016GL068842

|

|

Hu Chuanmin, Lee Zhongping, Franz B. 2012. Chlorophyll a algorithms for oligotrophic oceans: a novel approach based on three-band reflectance difference. Journal of Geophysical Research, 117(C1): C01011

|

|

Huang Boyin, Liu Chunying, Banzon V, et al. 2021. Improvements of the daily Optimum Interpolation Sea Surface Temperature (DOISST) version 2.1. Journal of Climate, 34(8): 2923–2939. doi: 10.1175/JCLI-D-20-0166.1

|

|

Hwang Cheinway, Chen Sung-An. 2000. Circulations and eddies over the South China Sea derived from TOPEX/Poseidon altimetry. Journal of Geophysical Research, 105(C10): 23943–23965. doi: 10.1029/2000JC900092

|

|

Jia Yinglai, Liu Qinyu. 2004. Eddy shedding from the Kuroshio bend at Luzon Strait. Journal of Oceanography, 60(6): 1063–1069. doi: 10.1007/s10872-005-0014-6

|

|

Kohonen T. 2001. Self-Organizing Maps. 3rd ed. Berlin: Springer Press, 501

|

|

Liu K K, Chao S Y, Shaw P T, et al. 2002. Monsoon-forced chlorophyll distribution and primary production in the South China Sea: observations and a numerical study. Deep-Sea Research Part I: Oceanographic Research Papers, 49(8): 1387–1412. doi: 10.1016/S0967-0637(02)00035-3

|

|

Liu Qinyu, Jiang Xia, Xie Shangping, et al. 2004. A gap in the Indo-Pacific warm pool over the South China Sea in boreal winter: seasonal development and interannual variability. Journal of Geophysical Research, 109(7): C07012

|

|

Liu Yonggang, Weisberg R H. 2007. Ocean currents and sea surface heights estimated across the West Florida Shelf. Journal of Physical Oceanography, 37(6): 1697–1713. doi: 10.1175/JPO3083.1

|

|

Liu Yonggang, Weisberg R H, Mooers C N K. 2006. Performance evaluation of the self-organizing map for feature extraction. Journal of Geophysical Research, 111(C5): C05018

|

|

Liu Zhengyu, Yang Haijun, Liu Qinyu. 2001. Regional dynamics of seasonal variability in the South China Sea. Journal of Physical Oceanography, 31(1): 272–284. doi: 10.1175/1520-0485(2001)031<0272:RDOSVI>2.0.CO;2

|

|

Lu Wenfang, Wang Jian, Jiang Yuwu, et al. 2022. Data-driven method with numerical model: a combining framework for predicting subtropical river plumes. Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans, 127(3): e2021JC017925

|

|

Lu Wenfang, Yan Xiaohai, Jiang Yuwu. 2015. Winter bloom and associated upwelling Northwest of the Luzon Island: a coupled physical-biological modeling approach. Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans, 120(1): 533–546. doi: 10.1002/2014JC010218

|

|

Martin M C, Villanoy C L. 2007. Sea surface variability of upwelling area Northwest of Luzon, Philippines. In: Tregoning P, Rizos C, eds. Dynamic Planet: Monitoring and Understanding a Dynamic Planet with Geodetic and Oceanographic Tools. Berlin: Springer, 84–87

|

|

Mears C A, Scott J, Wentz F J, et al. 2019. A near-real-time version of the Cross-Calibrated Multiplatform (CCMP) ocean surface wind velocity data set. Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans, 124(10): 6997–7010. doi: 10.1029/2019JC015367

|

|

Nan Feng, Xue Huijie, Chai Fei, et al. 2011. Identification of different types of Kuroshio intrusion into the South China Sea. Ocean Dynamics, 61(9): 1291–1304. doi: 10.1007/s10236-011-0426-3

|

|

Nan Feng, Xue Huijie, Yu Fei. 2015. Kuroshio intrusion into the South China Sea: a review. Progress in Oceanography, 137: 314–333. doi: 10.1016/j.pocean.2014.05.012

|

|

Nitani H. 1970. Oceanographic conditions in the Sea, Philippines and Luzon Strait in Summer of 1965 and 1966. In: Marr J D, ed. The Kuroshio: A Symposium on the Japan Current. Honolulu: East West Centre Press, 213–232

|

|

Pujol M. 2022. Product user manual for sea level SLA products. Copernicus Monitoring Environment Marine Service (CMEMS). https://catalogue.marine.copernicus.eu/documents/PUM/CMEMS-SL-PUM-008-032-068.pdf[2022-11-1]

|

|

Qu Tangdong. 2000. Upper-layer circulation in the South China Sea. Journal of Physical Oceanography, 30(6): 1450–1460. doi: 10.1175/1520-0485(2000)030<1450:ULCITS>2.0.CO;2

|

|

Roemmich D, Gilson J. 2001. Eddy transport of heat and thermocline waters in the North Pacific: a key to interannual/decadal climate variability?. Journal of Physical Oceanography, 31(3): 675–687

|

|

Shaw Ping-Tung, Chao Shenn-Yu, Liu Kon-Kee, et al. 1996. Winter upwelling off Luzon in the northeastern South China Sea. Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans, 101(C7): 16435–16448. doi: 10.1029/96JC01064

|

|

Sun Ruili, Gu Yanzhen, Li Peiliang, et al. 2016a. Statistical characteristics and formation mechanism of the Lanyu cold eddy. Journal of Oceanography, 72(4): 641–649. doi: 10.1007/s10872-016-0361-5

|

|

Sun Ruili, Li Peiliang, Gu Yanzhen, et al. 2022. Counter-rotating eddy pair in the Luzon Strait. Ocean Science, 18(3): 717–728. doi: 10.5194/os-18-717-2022

|

|

Sun Ruili, Ling Zheng, Chen Changlin, et al. 2015. Interannual variability of thermal front west of Luzon Island in boreal winter. Acta Oceanologica Sinica, 34(11): 102–108. doi: 10.1007/s13131-015-0753-1

|

|

Sun Chengxue, Liu Qinyu. 2011. Double eddy structure of the winter Luzon Cold Eddy based on satellite altimeter data. Journal of Tropical Oceanography (in Chinese), 30(3): 9–15

|

|

Sun Ruili, Wang Guihua, Chen Changlin. 2016b. The Kuroshio bifurcation associated with islands at the Luzon Strait. Geophysical Research Letters, 43(11): 5768–5774. doi: 10.1002/2016GL069652

|

|

Sun Ruili, Zhai Fangguo, Gu Yanzhen. 2018. The Four patterns of the East Branch of the Kuroshio bifurcation in the Luzon Strait. Water, 10(12): 1822. doi: 10.3390/w10121822

|

|

Tang Danling, Ni I H, Kester D R, et al. 1999. Remote sensing observations of winter phytoplankton blooms Southwest of the Luzon Strait in the South China Sea. Marine Ecology Progress Series, 191: 43–51. doi: 10.3354/meps191043

|

|

Tsui I-Fong, Wu Chau-Ron. 2012. Variability analysis of Kuroshio intrusion through Luzon Strait using growing hierarchical self-organizing map. Ocean Dynamics, 62(8): 1187–1194. doi: 10.1007/s10236-012-0558-0

|

|

Udarbe-Walker M J B, Villanoy C L. 2001. Structure of potential upwelling areas in the Philippines. Deep-Sea Research Part I: Oceanographic Research Papers, 48(6): 1499–1518. doi: 10.1016/S0967-0637(00)00100-X

|

|

Wang Guihua, Chen Dake, Su Jilan. 2008. Winter eddy genesis in the eastern South China Sea due to orographic wind jets. Journal of Physical Oceanography, 38(3): 726–732. doi: 10.1175/2007JPO3868.1

|

|

Wang Guihua, Li Jiaxun, Wang Chunzai, et al. 2012. Interactions among the winter monsoon, ocean eddy and ocean thermal front in the South China Sea. Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans, 117(C8): C08002

|

|

Wang Guihua, Su Jilan, Chu P C. 2003. Mesoscale eddies in the South China Sea observed with altimeter data. Geophysical Research Letters, 30(21): 2121. doi: 10.1029/2003GL018532

|

|

Wang Jiujuan, Tang Danling, Sui Yi. 2010. Winter phytoplankton bloom induced by subsurface upwelling and mixed layer entrainment southwest of Luzon Strait. Journal of Marine Systems, 83(3–4): 141–149

|

|

Zhang Zhiwei, Zhao Wei, Qiu Bo, et al. 2017. Anticyclonic eddy sheddings from Kuroshio Loop and the accompanying cyclonic eddy in the northeastern South China Sea. Journal of Physical Oceanography, 47(6): 1243–1259. doi: 10.1175/JPO-D-16-0185.1

|

|

Zheng Zhewen, Ho C R, Kuo N J. 2007. Mechanism of weakening of west Luzon eddy during La Niña years. Geophysical Research Letters, 34(11): L11604. doi: 10.1029/2007GL030058

|