| Citation: | Jihua Liao, Keqiang Wu, Lianqiao Xiong, Jingzhou Zhao, Xin Li, Chunyu Zhang. Dissolution mechanism of a deep-buried sandstone reservoir in a deep water area: A case study from Baiyun Sag, Zhujiang River (Pearl River) Mouth Basin[J]. Acta Oceanologica Sinica, 2023, 42(3): 151-166. doi: 10.1007/s13131-022-2142-x |

Deep-water and deep-buried hydrocarbon explorations have been significant domains with broad prospects (Tong et al., 2014; Jia and Pang, 2015; Feng et al., 2016). The occurrence, characteristics, and mechanisms of formation and distribution of favorable reservoir are key issues for hydrocarbon exploration. Deeply buried sandstone is under a complex field with various temperature, pressure, stress, and fluid, which is influenced by complex diagenetic interactions (Jia and Pang, 2015; He et al., 2019). Compared with exploration in inland areas, deeply buried exploration and research in deep-water and ultra-deep-water regions are currently at an early stage.

Dissolution is a key factor in the development of high-quality reservoirs in deeply buried sandstones (Chen et al., 2003; Lyu et al., 2011, 2014). Sandstones buried to depths more than 3500 m have been shown to considerable reservoir quality due to dissolution alteration (Lyu et al., 2014), although they have suffered from strong compaction and cementation. Meteoric water leaching (Mansurbeg et al., 2006; Kriete et al., 2004), CO2-bearing fluid (Wang et al., 2016), organic acids, and transformation of clay minerals (Chen et al., 2009) can lead to dissolution and the formation of secondary pores in deeply buried sandstones. This chemical diagenesis is directly influenced by factors, such as tectonic settings, sediment characteristics and temperature-pressure field.

Generally, meteoric leaching occurs near the sequence boundaries (Meng et al., 2002; Ketzer et al., 2003; El-Ghali et al., 2006; Ding et al., 2014). The leaching depths can reach to 2–3 km, depending on the pressure head and water level (Purvis, 1995). On the other hand, organic acids dissolution can lead to the formation of secondary pores (Purvis, 1995). Different kerogen types have different characteristics for generating acids (Yuan et al., 1996). Type III kerogens mainly consist of dibasic acids with a large dissolving capacity, can generate more content of acids compared to Type I and Type II kerogens.

Moreover, the objects and scale of dissolution are controlled by the content of soluble minerals, primary porosity, and lithological assemblage (Zhang et al., 2010). Additionally, the increase in porosity caused by the dissolution of feldspar was much greater than the decrease in porosity caused by the precipitation of kaolinite (Hayes and Boles, 1993). Therefore, the dissolution of feldspar is favorable for the formation of high-quality reservoirs. Varied solubility of soluble minerals, under-pressure of the succession and overpressure caused by hydrocarbon generation lead to overpressure in different environments with limited fluid flow (Osborne and Swarbrick, 1997; Kong et al., 2018; Lei et al., 2018a), which are unfavorable for cementation and favorable for the preservation of porosity (Osborne and Swarbrick, 1997).

The Baiyun Sag is a well-known prolific hydrocarbon-generated sag and a significant oil-gas production area in the Zhujiangkou Basin in the northern South China Sea (Shi et al., 2014; Zhang et al., 2021; Mi et al., 2022). A coal-bearing deltaic system developed during the Enping and Zhuhai depositional periods on the northern slope of the Baiyun Sag (Zhang et al., 2014). Type III kerogens with high thermal maturity are dominant and have potential to provide abundant acidic fluids for dissolution. Carbon dioxide and high CO2-bearing gas reservoirs were discovered in the Paleogene and Neogene sandstone reservoirs in the Baiyun Sag (Jin et al., 2013). The CO2 dissolved in the formation water leads to the dissolution of soluble minerals and the formation of secondary minerals.

In recent years, large-scale reservoirs with burial depths of more than 2 500 m have been drilled in the Baiyun Sag, and they have indicated great potential for the exploration of mid-deep buried reservoirs (Tian et al., 2020). As shallow to mid-buried exploration has progressed, deeply buried exploration has become a future target (Ma et al., 2017; Li et al., 2019; Pang et al., 2019). However, the mechanism and distribution of reservoirs remain unlcear in deep buried layers. The triggering mechanism, characteristics, and models of dissolution and the prediction of high-quality deep-buried reservoirs require further study. Hence, in this paper, the Enping and Zhuhai formations in Baiyun Sag of South China Sea was taken as a target. Based on the thin section, scanning electron microscopy, X-ray diffraction, porosity/permeability measurement, andmercury injection, influencing factors of dissolution were examined, and a dissolution model was established. Further, high-quality reservoirs were predicted temporally and spatially.

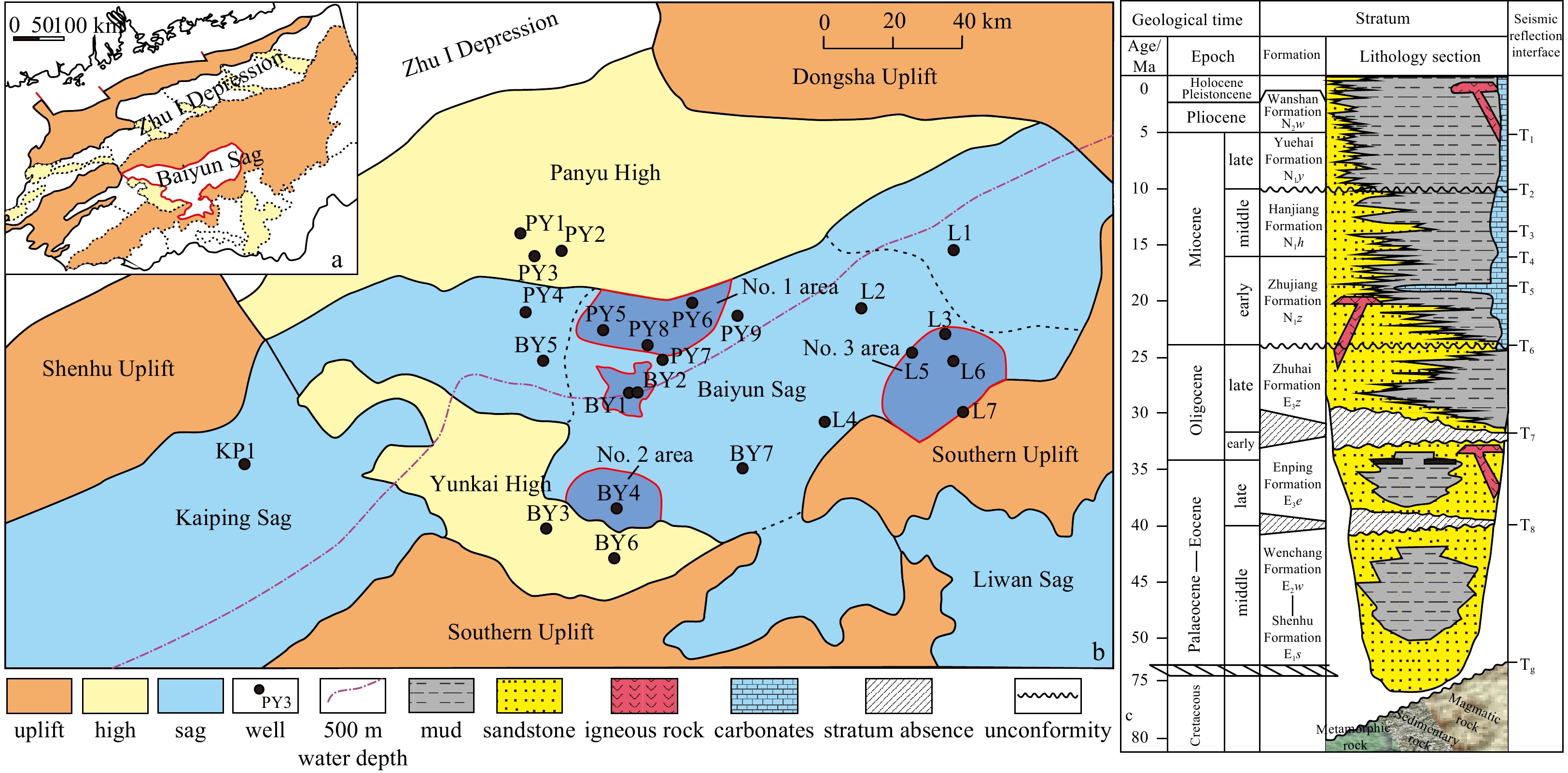

The Zhujiang River (Pearl River) Mouth Basin is a Cenozoic continental margin rift basin in the northern South China Sea. It has a northeast-southwest (NE−SW) orientation, covering an area of 1.75×105 km2. Owing to the interlaced uplift and depression in the basin, there is an obvious tectonic pattern of “north-south zoning and east-west zoning” (Shi et al., 2014; Zhu et al., 2019) (Fig. 1). The Baiyun Sag is located east of the Zhu II depression with the Panyu low uplift in the north, the Southern Uplift in the south, the Yunkai High in the west, and the Dongsha Uplift in the east. It can be divided into east, main, west, and south hydrocarbon-generated sub-sags. It covers an area of 1.21×104 km2. The maximum thickness of the Cenozoic succession was 11 000 m, and the current water depth is 200–2 000 m.

The Baiyun Sag has experienced three tectonic stages in the Cenozoic (Zhang et al., 2014), including the rifting period, thermal subsidence period, and neo-tectonic period. While, based on the detachment model, several researchers have suggested that tectonic evolution can be divided into detachment−rift, rift−post-rift, and subsidence stages (Lei et al., 2018b). Although different researchers have different opinions, these models indicate that the Baiyun Sag has experienced three stages: fault-controlled sedimentation, rift and post-rift transformation, and regional subsidence. During the Paleocene−Eocene fault-controlled sedimentation stage, the Baiyun Sag developed local depocenters and separated sub-sags. During the Oligocene rift and post-rift transformation stages, the faults only controlled the local sub-sags. Then, the depocenter and subsidence center shifted to the center of the Baiyun Sag, forming the main sag. Since the Miocene, the Baiyun movement has shifted to the south along the spreading ridge of the South China Sea. The shelf-slope break rapidly shifted from south to north (Liu et al., 2011), undergoing regional subsidence. Its stratigraphic succession was barely influenced by faulting.

The Baiyun Sag consists of the mid-lower Eocene Wenchang Formation (E2w), the upper Eocene-lower Oligocene Enping Formation (E3e), the upper Oligocene Zhuhai Formation (E3z), the Miocene Zhujiang Formation (N1z), the Hanjiang Formation (N1h), the Qionghai Formation (N1y), and the Pliocene Wanshan Formation (N2w). The sedimentary environments consist of terrestrial fluvial-lacustrine, shallow-water shelf, and deep-water slope environments (Fig. 1c) (Pang et al., 2008). The Wenchang Formation comprises fluvial deposits. The upper Enping Formation is dominated by shallow-water shelf deposits, including braided deltas, fan deltas, and shallow sea shelf deposits (Han et al., 2017; Zeng et al., 2017). The Zhuhai Formation is composed of a large-scale shelf deltaic system and shore shelf deposits. Since the early Miocene, the succession has been dominated by deep-water submarine fans and pelagic mud (Liu et al., 2011; Liao et al., 2016).

The Baiyun Sag is composed of three sets of source rocks: lacustrine source rock in the Wenchang Formation (E2w), marsh-derived source rock in the Enping Formation, and continent-derived marine source rock in the Zhuhai Formation (Long et al.,2020). Drilling wells from the east sub-sag penetrate shallow- to semi-deep-water lacustrine high-quality source rocks (Mi et al, 2019). Total organic carbon (TOC) from the Wenchang mudstone is approximately 1%–2.5%, and that from S1+S2 is approximately 0.42%–1.15%. The HI is approximately 163–288 HC/g TOC (Jiang et al., 2021). A large coal-bearing deltaic system with an area as large as 4 500 km2 was developed in the Enping and Zhuhai formations (Zhang et al., 2014). Drilling wells from the northern slope of the Baiyun Sag revealed 20 coal beds with a total thickness of up to 23 m. According to the organic geochemical analysis, coal-bearing source rocks (Type III, TOC is 0.34%–7.41%, S1+S2 is 0.3–19.08 mg/g) in the Enping Formation consisted of a mixture of aquatic algae and terrestrial plants, indicative of effective source rock (Li et al., 2013). The deep-water region in the Baiyun Sag had a narrower, shallower buried hydrocarbon-generated window and higher hydrocarbon-generated intensity because it was affected by the thin continental marginal crust, which was created by strong detachment, post-rift thermal subsidence discrepancy, and the high thermal flux caused by mantle uplift (Zhang and Chen, 2017; Pang et al., 2018; Mi et al., 2019).

The burial history of the Baiyun Sag was not complicated following the sedimentation of the Wenchang Formation. The drilling wells demonstrate that the succession was buried persistently with varied deposition rates and was never uplifted (Fu, 2019). The geothermal gradient ranges from 2.87–6.47℃/(100 m), and it is extremely high in areas affected by magmatism and faulting. Areas with a low geothermal gradient (<4.5℃/(100 m)) occur in the northern Baiyun sag, while high geothermal gradients (>4.5℃/(100 m)) occur in the main sag, the southwest, southeast, and Liwan sags. The pressure coefficient ranging from 0.9–1 is normal above 3800 m in the periphery and the interior of the sag, while its range of 1.3–1.55 was over-pressured below 3800 m in the main sag (Tian et al., 2020).

Sidewall core samples (55) from 14 wells (Fig. 1b) were obtained to conduct casting thin section observation and physical property test. The relationships between the occurrence and type of the secondary minerals and the temperature-pressure were built in 25 wells. Twenty samples from 5 wells were chosen to conduct SEM observation. Seven drilling wells with mercury injection data were chosen to build the relationship of the pore-throat digital model between the shallow-buried and deep-buried succession.

Sidewall core samples (55) from deep clastic rocks of 14 wells were processed into cylinders with a diameter of 25.4 mm and a length of 40 mm, and then the porosity and permeability of different lithofacies were analyzed by helium porosity meter and CMS-300 analysis equipment. Through particle size analysis, the relationship between particle size of different sedimentary facies zones was studied.

Samples (39) were selected for smash and screening. The screening particle size ranged from 0.031 mm to 32 mm. Twenty representative sidewall core samples from 5 deep drilling wells in Baiyun Sag were selected for SEM to describe the characteristics of micropores and secondary minerals. The scanning electron microscope adopts a Carl Zeiss supra 55 field emission electron microscope with an operating voltage of 5 kV and 30 μM standard grating and 40 s counting time was used to scan the samples.

The mineral compositions of 19 whole rock samples and 20 clay samples are analyzed by XRD (X-ray diffraction). The XRD equipment adopts X-ray diffractometer D8A (instrument No.: 00049672) and is calibrated with a goniometer (accuracy less than 0.02°2θ).

Due to the lack of mercury injection data of deep reservoir wall core samples in this study, the mathematical relationship model between porosity and permeability and pore throat radius (r35) is established by using mercury injection data of Zhujiang Formation or shallow Zhuhai Formation through 7 wells with mercury injection data, the pore throat radius is deduced by using the deep reservoir physical property data. To describe the relationship between the content of kaolinite and illite and ground temperature, 25 wells in Baiyun Sag are used to obtain the content of kaolinite and illite through element logging interpretation, and the temperature and pressure data in the middle and deep layers are obtained through the test data during drilling.

Lithic quartz sandstones, feldspathic lithic sandstones, and debris-arkosic sandstones are the main rock types in the deep burial strata of the Baiyun Sag. Four types of grain sizes were recognized in the Zhuhai Formation and Enping Formation: coarse-grained (Sc), medium-grained (Sm), fine-grained (Sf), and inequigranular sandstones (Sn).

(1) Coarse-grained sandstone (Sc): With a single particle size of more than 1 mm, dissolved pores were developed in the rock, calcite, and ankerite-filled pores (Fig. 2a). Dissolution can be observed in the ankerite crystals. This rock type has poor to medium sorting, angular to subcircular roundness, visible structural fractures, particle fractures, and intergranular dissolved pores (Fig. 2b). Primary intergranular pores were common (Fig. 2c). At the local area, intergranular pores, intergranular dissolved pores, structural joints, and fractures were developed in the rocks. At the edge of the particles, grained joints and feldspar dissolution pores were found(Fig. 2d). The test porosity and permeability ranged from 8.5%–14.1% and 0.13–213.87 mD, respectively.

(2) Medium-grained sandstone (Sm): This rock type exhibited poor to medium sorting, primarily angular to sub-circular particles. Dissolved pores and intragranular dissolved pores with low connectivity were developed (Fig. 2e). We can see calcite fills the pores (Fig. 2f), and Fe-rich dolomite fills the pores (Fig. 2g). The particles experienced significant dissolution (Fig. 2h). Test porosity and permeability ranged from 5.1%–7.3% and 0.10–16.63 mD, respectively.

(3) Fine-grained lithic feldspar sandstone (Sf): This rock type has a high argillaceous content, good particle sorting, and sub-angular particles. Intergranular pores and intergranular dissolved pores with poor pore connectivity were developed (Figs 2i and j). Calcite fills the pores in the local area (Fig. 2k). Test porosity and permeability ranged from 3.0%–5.5% and 0.09–9.91 mD, respectively.

(4) Inequigranular lithic quartz sandstone (Sn): The sorting of debris particles is extremely poor, which is distributed from silty particles to giant particles. The pores are primarily filled with mud. The grinding roundness of the giant debris particles is low, mainly angular-subangular (Fig. 2l). The physical properties of the rocks are extremely poor. Test porosity and permeability ranged from 5.0%–8.5 % and 0.09–0.25 mD, respectively.

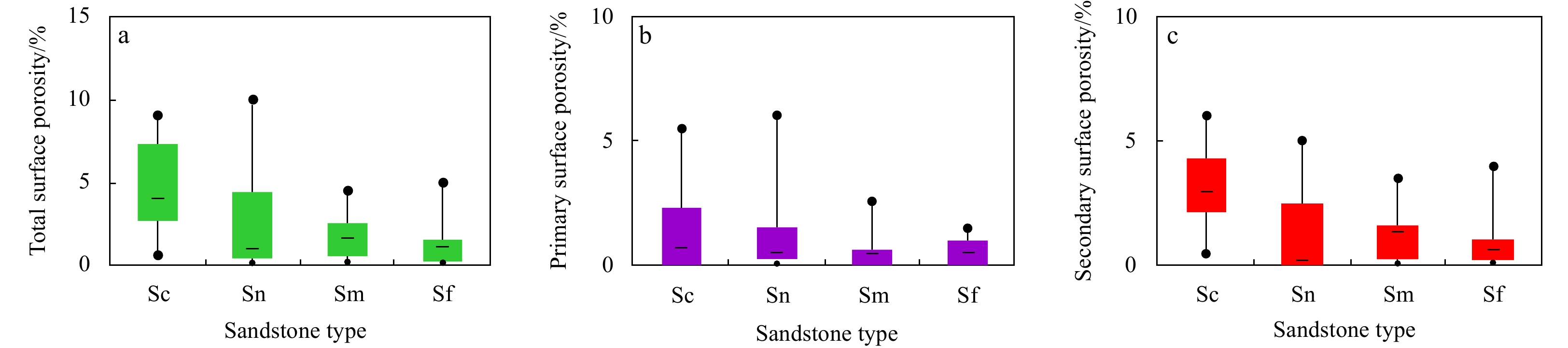

According to the statistical analysis of the surface porosity in the petrographic slices of the four lithofacies (Fig. 3), the average surface porosity of Sc was the highest, followed by that of Sm; that of Sn was the lowest (Fig. 3a). The primary surface porosity of the lithofacies was relatively low, with an average value of no more than 1% (Fig. 3b). The dissolution porosity accounted for more than 80% of the total (Fig. 3c), and the secondary dissolution porosity of Sc was the highest. Dissolution had the most obvious effect on medium-giant sand particles among the different grain sizes and induced a large increase in porosity, especially in the Sc lithofacies. Dissolution has a limited effect on fine-grained Sf and unequal-grained Sn lithofacies.

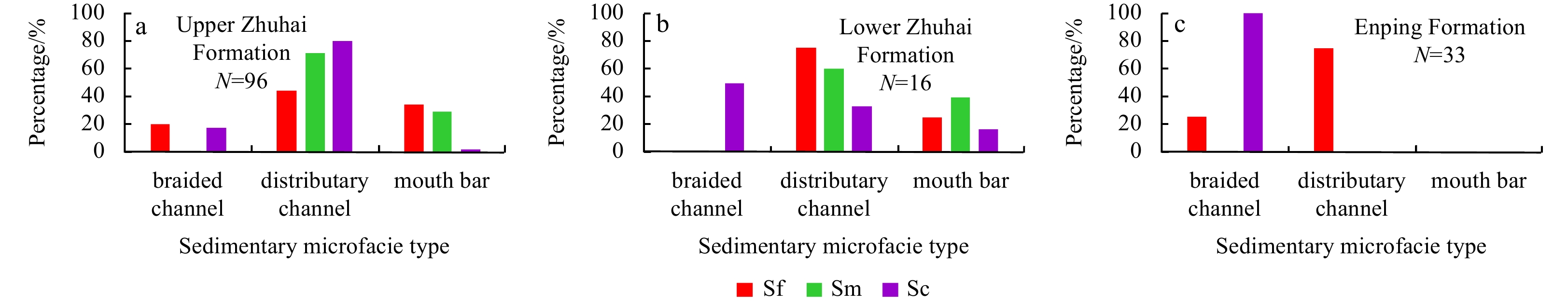

The deep strata in the Enping and Zhuhai formations in the Baiyun Sag primarily developed braided river and shallow shelf deltas, respectively (Han et al., 2017; Zeng et al., 2015). The delta plain subfacies can be identified as distributary channel and inter-distributary bay microfacies. The delta front subfacies can be identified as subaqueous distributary channel, subaqueous inter-distributary bay, and mouth bar microfacies (Zeng et al., 2015, 2017). Reservoir sand bodies are primarily distributed in distributary channels, subaqueous distributary channels, and mouth-bar microfacies. The lithofacies assemblages in the different sedimentary microfacies were different (Fig. 4). In general, the proportions of Sc and Sm in the distributary channel and subaqueous distributary channel sand body were high, while that in the mouth bar sand bodies were primarily Sf, with a small amount of Sc and Sm. The dissolution characteristics varied for different lithofacies; therefore, the dissolution characteristics of different microfacies are also different.

The distributary channel is located in braided river delta plain subfacies or continental shelf delta plain subfacies. The lithological assemblages are thick sand layers with thin mudstone beds, and the thickness of a single sand layer is usually greater than 10 m. The amount of gravel found in the braided river delta distributary channel is relatively high (Fig. 5a), constituting the coarsest particle size, and Sn is locally visible. The grain size in the distributary channel of the continental shelf delta is slightly finer and composed of medium-grained (Sm) and medium-fine-grained (Sm, Sf) lithic quartz sandstone. The compaction between the particles was tight, and dissolution pores developed locally (Fig. 2).

Subaqueous distributary channel: Evidence of combined lithology, mudstone color, and organic matter content of the mudstone and seismic facies (Fig. 5b) shows that the facies belt is located in a continental shelf edge or braided river delta front. It was primarily dominated by traction flow deposition. The particle size is finer than that of the delta plain, and gray medium-coarse (primarily Sm, Sc) and medium-fine (primarily Sm and Sf) lithic quartz sandstones were developed (Fig. 2f). Dissolution is significantly developed in feldspar and the matrix.

Mouth bar: This type of facies was located in the delta front of a continental shelf edge or braided river delta front (Fig. 5b). The sandstone particle of this facies was fine, and mudstone- siltstone was developed in the lower part of the facies. The upper part of the facies was medium-fine-grained (Sm, Sf) and muddy medium-fine-grained (Sf) lithic quartz sandstones (Figs 2d and e). The thickness of the sand body was generally less than 8 m, and the dissolution phenomenon was rare, leading to poor physical properties.

Dissolution is an important factor in improving reservoir quality in the middle and deep strata of the Baiyun Sag. Because of the acidic fluid, feldspar, lithic and tuffaceous heterobase, and other soluble substances were dissolved and formed secondary pores (Fig. 6). A pore-fracture network composed of fractures and pores can improve the physical properties of reservoirs. The dissolution pores developed in the middle-deep sandstone reservoirs. In most cases, dissolution pores occurred between or within debris particles with point-line, line, and concave-convex contacts. In the local area, authigenic quartz, ferroan calcite, and ankerite filled the dissolution pores, and near the dissolution pores, ferroan calcite or ankerite developed. This filled carbonate cement was also dissolved in later stages.

In the middle and deep sandstones of the study area, feldspar was dissolved (Figs 6a, b, d, and e), and the dissolution primarily expanded along the feldspar cleavage fracture (Fig. 6a). After feldspar dissolution, kaolinite remained, resulting in the surface of the residual feldspar particles becoming dirty (Fig. 6a). The pores of the incompletely dissolved feldspar particles were filled with authigenic quartz and ankerite (Fig. 6d). When the dissolution was severe, the feldspar particles were almost completely dissolved, forming mold pores (Fig. 6e). Petrological mineral composition analysis showed that the middle-deep clastic rock debris in the Baiyun Sag was primarily composed of metamorphic and igneous rock debris, in which the igneous rock debris was primarily granite and the metamorphic rock debris included quartzite and phyllite. The granite cuttings were rich in quartz and feldspar, and the quartzite cuttings are primarily metamorphic quartz. The mineral assemblages of the phyllite cuttings include sericite, chlorite, and quartz. Granite cuttings can also form intragranular dissolution pores through feldspar dissolution (Fig. 6f).

In the deep clastic reservoirs in the study area, tuff was filled among clastic particles in the form of a matrix (Fig. 6g). The original tuff component was unstable, and transformation and dissolution occurred during the late diagenesis period(Tian et al, 2020). Owing to the acidic fluid, tuff was easily dissolved, forming intergranular dissolved pores among clastic particles (Fig. 6c), which improved the physical properties of the reservoir to a certain extent.

The early bright crystal calcite filled the intergranular pores in a heteromorphic form, and the size of the cement particles was similar to that of the debris particles (Fig. 6h). A small amount of dissolution was observed at the edge of the calcite cement. Ankerite can fill intergranular pores (Fig. 6h) and intragranular dissolved pores (Figs 6e and i). In addition to the filling of intergranular pores or intergranular dissolved pores, ankerite can replace feldspar, debris, and tuffaceous heterobases (Fig. 6j) and can also be dissolved (Figs 6i and j).

Secondary pores formed by dissolution are the main pore types in the middle and deep reservoirs. The types of dissolution pores included intergranular and intragranular dissolution pores (Figs 6a, d, and e). The dissolution substances included feldspar, tuffaceous matrix, and ankerite cement, and feldspar dissolution was the main type (Figs 6a, d, e, k, and l). Intragranular dissolved pores primarily manifested along feldspar cleavage joints or cracks (Figs 6a and l). The evolution from intragranular to intergranular dissolved pores may be one of the main methods for forming intergranular dissolution pores.

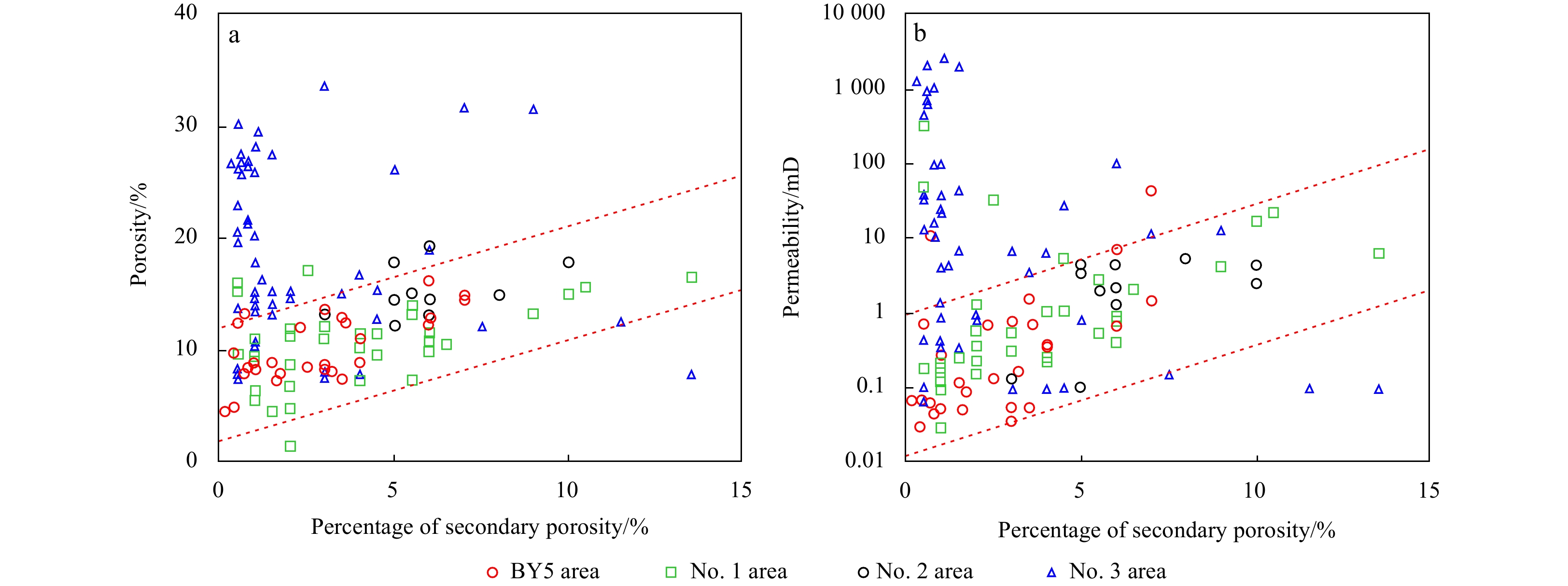

Secondary pores are the main type of pores (Fig. 6), and dissolution pores have a positive effect on improving the physical properties of the middle to deep reservoirs (Fig. 7). Except the secondary pores from the Zhujiang and upper Zhuhai Formations in the eastern Baiyun Sag that are not developed, the secondary pores are developed in the Zhuhai and Enping formations in the northern slope, Well BY5 area, and southwest of the Baiyun Sag (Fig. 7). Secondary porosity has a good positive correlation with porosity and permeability, indicating that the secondary dissolution pores have a positive effect, improving the physical properties of deep reservoirs. The burial depths of the Baiyun North Slope and Well BY5 area are large, and the deep strata are dominated by dissolved pores. The proportion of dissolved pores increased with increasing burial depth in the Well BY5 area (Fig. 7). Secondary surface porosity in the north slope and BY5 had a good positive correlation with porosity and permeability (Fig. 8). Secondary porosity is of great significance for improving the porosity and permeability of deep strata.

The pore structure was primarily based on the mercury injection data of the Zhujiang and upper Zhuhai formations, and a mathematical relationship model between porosity and permeability with pore throat radius (r35) was established. The pore-throat radius was deduced using the physical property data of the deep reservoirs, and r35 is the pore-throat radius corresponding to 35% mercury saturation (SHg) on the mercury injection curve, which is an important parameter for characterizing the pore throat structure. r35 can also be called pore throat size (port size), and the pore throat system can be divided into five types: (1) mega-pore (r35>10 μm), (2) macro-pore (2.5–10 μm), (3) meso-pore (0.5–2.5 μm), (4) micro port (0.1–0.5 μm), (5) nano port (r35<0.1 μm). Before mercury saturation reaches 35%, this portion of the pore throat may be an effective network for controlling fluid flow in the pore system. Before SHg reaches 35%, this portion is composed of relatively large pore throats in the network; thus, r35 is practically the same as the peak pore throat diameter.

Using the measured mercury injection data of Wells KP1, L1, L3, L4, L5, PY7, and PY8, the pore throat radius corresponding to 35% mercury saturation (SHg) on the mercury injection curve (Fig. 9a) was read, and the mathematical relationship model of pore throat radius (r35) with porosity and permeability was established: r35=0.289 3 (K/Φ) 0.4628 (Fig. 9b). Using this formula, the r35 curve was calculated. By integrating the physical property data, a porosity-permeability diagram and pore throat radius chart was prepared (Fig. 9). Based on the data of drilling depth below 3500 m in the Panyu Uplift–Baiyun North Slope, the reservoir fluid type is a result of logging interpretation, and the physical properties are the measured data. The reservoir with K>0.2 mD is primarily composed of micron pores (r>0.5 μm). The reservoir with K>1 mD was dominated by pores above 2 μm (r>1 μm) (Fig. 9).

The intergranular dissolved pores were filled with dissolved residues and kaolinite (Fig. 6k), indicating that dissolution occurred under semi-closed to closed conditions. Poor fluid flow conditions are not conducive to the migration of dissolved products. The dissolution of tuff also led to the formation of secondary pores in the middle and deep strata (Fig. 6g), but its effect on improving the reservoir porosity and permeability conditions may be limited. This is because the tuff forms chlorite and illite after dissolution, and clay minerals remain in the pores, which does not significantly improve the reservoir properties. In addition, silicon in the dissolution product precipitated in the form of quartz.

Kaolinite: After feldspar dissolution was observed in the middle-deep Zhuhai Formation of the Baiyun Sag, residual kaolinite accumulated in situ (Figs 6k, l). SEM images of the Wenchang Formation show that scale-like kaolinite coexisted with filamentous illite (Fig. 6m). The increase in kaolinite content also indicated the strong dissolution of feldspar. Authigenic kaolinite was primarily related to feldspar dissolution, i.e., the kaolinization of feldspar (Eq. (1)). Feldspar was dissolved in an acidic fluid to form kaolinite, SiO2, and secondary pores. Owing to the poor migration ability of Al3+, new kaolinite was precipitated near the dissolution particles.

Kaolinization of feldspar (Huang et al., 2009):

| $$ \begin{split} &2{\rm{KAlSi}}_3 {\rm{O}}_8 ({\rm{potassium}}\; {\rm{feldspar}})+2{\rm{H}}^+ +2{\rm{H}}_2 {\rm{O}}\\ & ={\rm{Al}}_2 {\rm{Si}}_2 {\rm{O}}_5 ({\rm{OH}})_4 ({\rm{kaolinite}})+4{\rm{SiO}}_2 +2{\rm{K}}^+. \end{split} $$ | (1) |

Illite: Illite can be converted from smectite, and the illite-montmorillonite mixed layers can be converted from feldspar and kaolinite reactions in a closed diagenetic environment (temperature is generally higher than 120℃) (Eq. (2)). SEM of middle-deep reservoir samples in the Baiyun Sag shows that illite filled in intergranular pores (Fig. 6n), and the dissolved potassium feldspar as symbiotic with filiform illite and a variety of secondary minerals. In the Enping Formation of Well PY1, illite filled the pores between authigenic quartz, indicating that illite formed later than the quartz (Fig. 6n). In the Zhuhai Formation of Well L4, illite filled the intergranular pores of dolomite, indicating that illite formed later than dolomite (Fig. 6o). In the Zhuhai Formation of Well BY1, the coexistence of calcite and illite (Fig. 6p) indicates that illite formed later than calcite.

Illitezation of kaolinite (Huang et al., 2009):

| $$ \begin{split} & 2{\rm{KAlSi}}_3 {\rm{O}}_8 ({\rm{potassium}}\; {\rm{feldspar}})+ {\rm{Al}}_2 {\rm{Si}}_2 {\rm{O}}_5 ({\rm{OH}})_4 ({\rm{kaolinite}})\\ & = {\rm{KAl}}_3 {\rm{Si}}_3 {\rm{O}}_{10} ({\rm{OH}})_2 ({\rm{illite}})+ 2{\rm{SiO}}_2 + {\rm{H}}_2 {\rm{O}}. \end{split} $$ | (2) |

Secondary enlargement of quartz: kaolinization of feldspar (Eq. (1)) and illitization of kaolinite (Eq. (2)) formed siliceous substances that dissolve in the underground fluid. A quartz secondary enlargement edge was formed at the edge of the clastic particles (Fig. 6q). According to the contact relationship between the secondary enlargement of quartz and clastic particles, at least three stages of secondary quartz enlargement were identified (Fig. 6r). In addition to the secondary enlargement of quartz, microcrystalline quartz coexists with pyrite and illite in the pores (Fig. 6s). From the coexistence relationship between quartz secondary enlargement, ferrocalcite, and ankerite, quartz secondary enlargement depends on the growth of quartz particles, and ferrocalcite and ankerite grow in the pores outside the secondary quartz (Fig. 6t). This indicates that the formation time of ferrocalcite and ankerite was later than that of the enlargement.

Coarse- (Sc) and medium-grained sandstone (Sm) possess higher primary porosities than fine-grained sandstone (Sf). Furthermore, high primary porosity is beneficial for the injection of acidic fluid, which is favorable for dissolution. Consequently, medium- and coarse-grained sandstone also present high total porosity, secondary porosity, and dissolution pore volumes (Fig. 3). Medium- and coarse-grained sandstone developed in distributary channels and subaqueous distributary channel sand bodies (Fig. 4). At the same burial depth, distributary channel sand bodies and subaqueous distributary channel sand bodies have higher porosity, permeability, surface porosity and dissolved pores than mouth bar sand bodies. Thus, distributary channel sand bodies and subaqueous distributary channel sand bodies are the main carriers of favorable deep reservoirs (Fig. 10).

The dissolution was related to organic acids derived from the source rocks. The interface between the sand body and source rocks can be easily affected by organic acids. A slightly negative correlation can be shown between the thickness of deep sand bodies ( superimposed or composite ) and the degree of secondary pore development in Baiyun Sag (Fig. 11a). However, dissolved porosity possess high values when the distances between the sand body and source rocks below 6 m (Fig. 11b). It can be suggested that dissolution by organic acids is effective near the interface between the sand body and source rocks (<6 m). In addition, compared with thick massive sandstone, sandstone with sand-mud interbedded structures is more likely to be modified by organic acid.

The organic acids formed by the thermal evolution of source rocks, namely formic, acetic and oxalic acid. The thermal simulation experiment of organic acid showed that through decarboxylation, oxalic acid disappeared at approximately 160℃, formic acid disappeared at approximately 260℃, and the pH increased accordingly. Acetic acid is stable and can maintain a stable concentration at high temperatures, while the solution maintains an acidic environment (Li et al., 2019). In addition to the formation of organic acids, liquid hydrocarbons, and gaseous hydrocarbons, CO2 can be generated during the thermal evolution of kerogens. Liquid hydrocarbons also formed CO2 during the cracking stage at high-temperature. With an increase in maturity, the CO2 yield increasingly (Wang et al., 2015). Favorable conditions for the formation and preservation of organic acids are thought to occur in the deep layer of the Baiyun Sag.

During the process of feldspar kaolinization, feldspar dissolution is caused by organic acids, which are closely related to source rock types and thermal evolution. There are three sets of source rock series in the Baiyun Sag: the Zhuhai, Enping, and Wenchang formations. At present, they have reached the mature or over-mature stage and experienced organic acid formation and explosion (Zhu et al., 2008; Zhang et al., 2014). Thermal simulation experiments of coal and mudstone show that CO2 concentration increases with an increasing maturity, and the high value of organic acid concentration is in the stage of 0.6%–1.5% of Ro. The coal deltas of the Enping Formation to Zhuhai Formation in the northern Baiyun Sag are widely distributed (Han et al., 2017; Zeng et al., 2017), mainly Type II and Type III kerongen. The main stage of organic acid formation was 23.3–16.5 Ma (Zhang et al., 2014), which can provide a large number of acidic fluids for dissolution (Li et al., 2019).

The Zhuhai and Enping formations in the Baiyun Sag are characterized by high temperatures and pressures. Strata below the Enping Formation develop strong overpressure causing by hydrocarbon (Tian et al., 2020). The pressure simulation revealed that the overpressure formation time of the Enping Formation was approximately 16 Ma, and that of the Zhuhai Formation was approximately 12 Ma. Wells BY1 and BY2 were drilled in the overpressure zone from the bottom of the Zhujiang Formation to the top of the Enping Formation, and vitrinite reflectance Ro gradually changed from low to high maturity. The pressure coefficient gradually increased from approximately 1.2 at the bottom of the Zhujiang Formation to overpressure in the Zhuhai and Enping formations, and the organic acid formation was consistent with overpressure formation. At present, the pressure coefficient of overpressure formation drilled in the Baiyun Sag is between 1.3 and 1.53, which is in the pressure transition zone (pressure coefficient 1.2–1.7). There are no deeper (pressure coefficient 1.7–1.95) or strong overpressure zones (pressure coefficient greater than 1.95).

The reaction efficiency between the acidic fluid and soluble minerals can be increased by overpressure (Zhang et al., 2013). Organic acid can migrate from the high-pressure area to the low- or normal-pressure areas. The action range of organic acid fluid is not only limited to the reservoir adjacent to the source rock but is also conducive to the migration of dissolved substances. Secondary pores were dominant in the overpressure interval, and the development degree of dissolved pores increased with the increasing pressure coefficient (Fig. 12).

In addition, when the pressure coefficient was 1.2, the proportion of secondary pores in medium-coarse grained sandstone was 50%–80%, whereas the proportion of secondary pores in sandstone with grains smaller than medium grains was only 20%–40%. When the pressure coefficient increased to 1.4, the proportion of secondary pores in medium-coarse-grained sandstone was 80%–100%, while the proportion of secondary pores in sandstone below medium-grain size increased to 60%–100%, indicating that dissolution was significantly enhanced for sandstones of different grain sizes.

Active faults are conducive to the development of fractures, which is of great significance in promoting dissolution and improving the physical properties of reservoirs. Taking the upper member of the Zhuhai Formation as an example, secondary porosities within sandstone are quart different in the fault development zone, the periphery of the fault development zone, and the non-fault zone (Fig. 13). Precisely, secondary porosity in the fault development zone is 4.13%–5.3% (Wells PY9 and BY4), is 0.88%–1.79% in the periphery of the fault development zone (PY8, BY5, BY1, and L5), and is 0.5% in the non-fault zone (Well L1).

In addition, the feldspar dissolved and formed intergranular and intragranular dissolved pores without obvious kaolinite cement in the fault development area of the upper member of the Zhuhai Formation. In contrast, pore spacesbwere filled with kaolinite near the fault and non-fault area of the upper member of the Zhuhai Formation. Hence, the dissolution in the fault development area is stronger and conducive to the migration of dissolved substances.

Kaolinization of feldspar and illitization of kaolinite are two pathways of feldspar dissolution. The formation of dissolution (secondary) pores are closely related to temperature (Chuhan et al., 2000) and has the following stages.

(1) Kaolinization of feldspar

Feldspar dissolves owing to the acidic fluid, and forms kaolinite and quartz. Kaolinite typically precipitates near the dissolution pores, and siliceous minerals may partially migrate or remain near the pores to form quartz overgrowth. The formation temperature of this stage is generally lower than 120–140℃. Low K+/H+ requires an open-semi open system with acidic fluid injection and K+ explosion.

(2) Illitization of kaolinite

When K+/Al3+>1:3, there is no need for acidic fluid intervention. Potassium feldspar and kaolinite can react to form illite and quartz. This reaction can occur at temperatures above 120–140℃ (Huang et al., 2009). Generally, kaolinite is not distributed near the dissolution pores of feldspar, and it coexists with filamentous illite. Illite covers the surface of clastic particles or carbonate cement in a filamentous form, filling pores and blocking throats in a bridging manner. Although it can increase the total porosity, it harms the connectivity of the pores and seepage conditions.

On the other hand, kaolinization of feldspar and illitization of kaolinite stages are significantly different in the various geothermal gradient areas (Gra).

① Gra≤4.5℃/(100 m)

At a shallow burial depth of 2 000 m with formation temperature of 100℃, the content of kaolinite decreases with burial depth, and dissolved pore becomes the main pore type with increasing trend in the deep layer (Fig. 14). Illitization of kaolinite is main action at a shallow burial depth of 2 000 m with formation temperature of 100℃. At depths of approximately 3 000 m and above 140℃, the illitization of kaolinite ceased and entered the stage of dissolution pore retention (Fig. 14).

② Gra>4.5°C/(100 m)

At a shallow burial depth of 1500 m and formation temperature of 80°C, no decreasing trend can be observed in the development of dissolution pores, and illitization of kaolinite is main action. At a depth of 2500 m and above 120℃, the dissolved pores become the main pore type (Fig. 15), and the illitization of kaolinite ceases.

Therefore, the temperature boundary of the transformation from the kaolinization of feldspar stage to the illitization of kaolinite stage was approximately 80℃, and the temperature boundary of the termination of the illitization of kaolinite stage was approximately 120℃. Then, it enters the stage of dissolution pore retention (Fig. 15). Below the two conversion depths of the sandstone reservoir dissolution pores did not significantly reduce (Figs 14 and 15), suggesting that these depths retain conditions of dissolution and formation of secondary pores. Because of the limited number of deep samples, the above depth and temperature boundaries may not objectively reflect the conversion depth and temperature of the two processes.

Medium-and coarse-grained sandstone present high sedimentary thickness in the upper member of the Enping Formation and lower member of the Zhuhai Formation, supplying the main material basis for dissolution. The kerogen types of the coal-bearing source rock in Enping and Zhuhai formations are primarily II–III, with Ro at 0.6%–1.5% in the stage of 23.8–13.8 Ma, which can provide a large amount of acidic fluid for dissolution. Overpressure can be formed due to hydrocarbon generation and pressurization (23.8–16.5 Ma). The contact time and strength between the acidic fluid and soluble minerals increased. Moreover, fault activity intensity is large during 23.8–10.5 Ma, and the average activity rate is 12–20 m/Ma. The fault is the main channel of overpressure transmission and a favorable development area for fractures.

During 23.8–13.8 Ma, the thermal evolution of the Enping and Zhuhai formations source rocks in the Baiyun Sag resulted in high organic acid concentration, overpressure development (pressure coefficient>1.2), and high fault activity rate. At this stage, the spatial superposition area of the medium-and coarse-grained facies belt, source rock, overpressure, and the fault is favorable for dissolution and pore increase in the sandstone reservoirs of the Enping and Zhuhai formations in the Baiyun Sag. Taking the north slope of Baiyun Sag as an example, using the calculation method of diagenesis pore reduction proposed by Ehrenberg (1989), the pore increase of sandstone reservoirs is shown to be 0.33%–11.01%, with an average value of 2.09%.

The dissolution of the sandstone reservoir of Enping and Zhuhai formations in the deep layer of the Baiyun Sag is controlled by factors such as medium and coarse-grained sedimentary facies belt, coal-bearing source rock evolution, overpressure evolution, and fault activity, and the strong dissolution often occurs in the synchronous coupling stage of these four factors (Fig. 16). In addition, both kerogen thermal evolution and liquid hydrocarbons form CO2 in the high-temperature cracking stage, and the CO2 yield increases with an increase in maturity (Wang et al., 2015). Favorable conditions are maintaining an acidic environment in the deep layer of the Baiyun Sag, and dissolution likely occurs in the deep layer.

During the sedimentary period of the lower and middle parts of the Enping Formation, the Baiyun Sag was supplied by peripheral uplift. Small braided river and fan deltas developed locally on the northern slope of the Baiyun Sag, southwest fault terrace belt, and Liuhua uplift belt. Although there are medium-and coarse-grained sand bodies of distributary and subaqueous distributary channels, the burial depth is large (the buried depth on the north slope of the Baiyun Sag is more than 6 000 m). Although this has not been revealed by drilling at present, favorable reservoirs are limited or not developed as a whole.

During the sedimentary period of the upper member of the Enping Formation, the northern part of the Baiyun Sag was supplied by the distant material source of the South China fold belt. A large braided river delta deposit developed on the northern slope of the Baiyun Sag. The distributary and subaqueous distributary channel sand bodies were widely developed (buried depth 3 200–4 500 m), and the shale content was generally less than 10%. From 23.8 Ma–13.8 Ma, Ro of the coal-bearing source rocks of the Enping and Zhuhai formations is 0.6%–1.5%, and the current pressure coefficient is 1.2–1.4. The faults are widely developed, and the activity intensity is large. The dissolution pores and fractures developed in the sandstone reservoir in the superposition area and the distributary and subaqueous distributary channel sand bodies, which is a favorable reservoir area. In the southwest fault step and Liuhua uplift belts, small fan deltas with near-source supplies are inherited. The fan delta plain and front subfacies develop the medium-and coarse-grained sandstones of the distributary channel and subaqueous distributary channel (burial depth is 2 000–3 000 m). The coal-bearing source rocks, overpressure, and fault space overlap well and are speculated to be favorable reservoir areas.

During the sedimentary period of the Zhuhai Formation, the Baiyun Sag was a shallow-shelf sedimentary environment. The peripheral uplift or low uplift has become an underwater highland, which receives the distant provenance supply of the South China fold belt, develops a unified large shelf delta, and extends to the main depression and south Baiyun Sag. From the early to the late stage of the Zhuhai Formation, marine transgression occurs, and medium-and coarse-grained sandstones are developed in the distributary and subaqueous distributary channel microfacies in the lower section of the Zhuhai Formation. During this period, the medium-and coarse-grained facies belt, coal-bearing source rock, overpressure, and fault space superposition on the northern slope of the Baiyun Sag (burial depth of 2 500–4 000 m) and southwest fault terrace belt (1 500–3 000 m) were good, which was speculated to be a favorable reservoir area.

(1) The dissolution of the Enping and Zhuhai formations in the Baiyun Sag developed in the coarse-grained (Sc) and medium-grained sandstone (Sm) lithofacies of distributary channel and subaqueous distributary channel microfacies, and the pore enhancement of fine-grained, below-sandstone (Sf), and inequigranular sandstone (Sn) lithofacies is limited. The dissolved minerals include feldspar, tuffaceous matrix, and cement, in which the cement is the dissolution of bright calcite and ankerite formed in the early stage, whereas the secondary dissolution pores are the main reservoir space in the deep layer of the Baiyun Sag.

(2) Kaolinization of feldspar and illitization of kaolinite are two pathways of dissolution and the formation of dissolution (secondary) pores. In the area of Gra≤4.5℃/(100 m), kaolinization of feldspar occurs at the shallow burial depth of 2000 m and below the temperature of 100℃, and illitization of kaolinite ceases above 140℃ and enters the stage of dissolution pore retention. While in the area with Gra>4.5℃/(100 m), kaolinization of feldspar occurs at a shallow depth of 1 500 m and temperature below 80℃, and illitization of kaolinite ceases above 120℃.

(3) The dissolution of the Enping and Zhuhai formations is jointly controlled by factors such as medium-and coarse-grained sedimentary facies belts, the evolution of coal-bearing source rocks, overpressure evolution, and fault activity. From 23.8–13.8 Ma, the four were synchronously coupled into the development stage of strong dissolution. The sand body development area of the distributary and subaqueous distributary channels in the upper part of the Enping Formation and the lower part of the Zhuhai Formation on the northern slope of the Baiyun Sag are favorable reservoir areas, and the sand body development area of the near-source fan delta and subaqueous distributary channels in the upper part of the Enping Formation in the southwest fault terrace belt and Liuhua uplift belt are favorable reservoir areas.

|

Chen Guojun, Du Guichao, Zhang Gongcheng, et al. 2009. Diagenesis and main factors controlling the tertiary reservoir properties of the Panyu Low-Uplift Reservoirs, Pearl River Mouth Basin. Natural Gas Geoscience (in Chinese), 20(6): 854–861

|

|

Chen Ronghua, Xu Jian, Meng Yi, et al. 2003. Microfossils, carbonate lysocline and compensation depth in surface sediments of the northeastern South China Sea. Acta Oceanologica Sinica, 22(4): 597–606

|

|

Chuhan F A, Bjørlykke K, Lowrey C. 2000. The role of provenance in illitization of deeply buried reservoir sandstones from Haltenbanken and north Viking Graben.off shore Norway. Marine and Petroleum Geology, 2000, 17: 673-689

|

|

Ding Xiaoqi, Han Meimei, Zhang Shaonan, et al. 2014. Roles of meteoric water on secondary porosity of siliciclastic reservoirs. Geological Review (in Chinese), 60(1): 145–158

|

|

Ehrenberg S G. 1989. Assessing the relative importance of compaction processes and cementation to reduction of porosity in sandstones: Discussion; Compaction and porosity evolution of Pliocene sandstones, Ventura Basin, California: Discussion1. AAPG Bulletin, 73(10): 1274–1276

|

|

El-Ghali M A K, Mansurbeg H, Morad S, et al. 2006. Distribution of diagenetic alterations in fluvial and paralic deposits within sequence stratigraphic framework: Evidence from the Petrohan Terrigenous Group and the Svidol Formation, Lower Triassic, NW Bulgaria. Sedimentary Geology, 190(1–4): 299–321

|

|

Feng Jiarui, Gao Zhiyong, Cui Jinggang, et al. 2016. The exploration status and research advances of deep and ultra-deep clastic reservoirs. Advances in Earth Science (in Chinese), 31(7): 718–736

|

|

Fu Jian. 2019. The study of hydrocarbon generation mechanism of source rocks and origin of oil in the Baiyun Sag, Pearl River Mouth Basin (in Chinese)[dissertation]. Beijing: China University of Petroleum (Beijing).

|

|

Han Yinxue, Chen Ying, Yang Haizhang, et al. 2017. “Source to sink” of Enping Formation and its effects on oil and gas exploration in Baiyun Sag, Pearl River Mouth Basin. China Petroleum Exploration (in Chinese), 22(2): 25–34

|

|

Hayes M J, Boles J R. 1993. Evidence for meteoric recharge in the San Joaquin Basin, California provided by isotope and trace element chemistry of calcite. Marine and Petroleum Geology, 10(2): 135–144. doi: 10.1016/0264-8172(93)90018-N

|

|

He Dengfa, Ma Yongsheng, Liu Bo, et al. 2019. Main advances and key issues for deep-seated exploration in petroliferous basins in China. Earth Science Frontiers (in Chinese), 26(1): 1–12

|

|

Huang Sijing, Huang Keke, Feng Wenli, et al. 2009. Mass exchanges among feldspar, kaolinite and their influences on secondary porosity formation in clastic diagenesis—A case study on the Upper Paleozoic, Ordos Basin and Xujiahe Formation, Western Sichuan Depression. Geochimica (in Chinese), 38(5): 498–506

|

|

Jia Chengzao, Pang Xiongqi. 2015. Research processes and main development directions of deep hydrocarbon geological theories. Acta Petrolei Sinica (in Chinese), 36(12): 1457–1469

|

|

Jiang Wenmin, Li Yun, Yang Chao, et al. 2021. Organic geochemistry of source rocks in the Baiyun Sag of the Pearl River Mouth Basin, South China Sea. Marine and Petroleum Geology, 124: 104836. doi: 10.1016/j.marpetgeo.2020.104836

|

|

Jin Xiaohui, Lin Qing, Fu Ning, et al. 2013. Impact of CO2 on formation and distribution of gas hydrate in northern South China Sea. Petroleum Geology & Experiment (in Chinese), 35(6): 634–639,645

|

|

Ketzer J M, Holz M, Morad S, et al. 2003. Sequence stratigraphic distribution of diagenetic alterations in coal-bearing, paralic sandstones: evidence from the Rio Bonito Formation (early Permian), southern Brazil. Sedimentology, 50(5): 855–877. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3091.2003.00586.x

|

|

Kong Lingtao, Chen Honghan, Ping Hongwei, et al. 2018. Formation pressure modeling in the Baiyun Sag, northern South China Sea: Implications for petroleum exploration in deep-water areas. Marine and Petroleum Geology, 97: 154–168. doi: 10.1016/j.marpetgeo.2018.07.004

|

|

Kriete C, Suckow A, Harazim B. 2004. Pleistocene meteoric pore water in dated marine sediment cores off Callao, Peru. Estuarine, Coastal and Shelf Science, 59(3): 499–510

|

|

Lei Chuan, Luo Jinglan, Pang Xiong, et al. 2018a. Impact of temperature and geothermal gradient on sandstone reservoir quality: the Baiyun Sag in the Pearl River Mouth Basin study case (northern South China Sea). Minerals, 8(10): 452. doi: 10.3390/min8100452

|

|

Lei Chao, Ren Jianye, Pang Xiong, et al. 2018b. Continental rifting and sediment infill in the distal part of the northern South China Sea in the western Pacific region: Challenge on the present-day models for the passive margins. Marine and Petroleum Geology, 93: 166–181. doi: 10.1016/j.marpetgeo.2018.02.020

|

|

Li Youchuan, Fu Ning, Zhang Zhihuan. 2013. Hydrocarbon source conditions and origins in the deepwater area in the northern South China Sea. Acta Petrolei Sinica (in Chinese), 34(2): 247–254

|

|

Li Chi, Luo Jinglan, Hu Haiyan, et al. 2019. Thermodynamic impact on deepwater sandstone diagenetic evolution of Zhuhai Formation in Baiyun Sag, Pearl River Mouth Basin. Earth Science (in Chinese), 44(2): 572–587

|

|

Liao Jihua, Xu Qiang, Chen Ying, et al. 2016. Sedimentary characteristics and genesis of the deepwater channel system in Zhujiang Formation of Baiyun-Liwan Sag. Earth Science (in Chinese), 41(6): 1041–1054

|

|

Liu Baojun, Pang Xiong, Yan Chengzhi, et al. 2011. Evolution of the Oligocene−Miocene shelf slope-break zone in the Baiyun deep-water area of the Pearl River Mouth Basin and its significance in oil-gas exploration. Acta Petrolei Sinica (in Chinese), 32(2): 234–242

|

|

Long Zulie, Chen Cong, Ma Ning, et al. 2020. Geneses and accumulation characteristics of hydrocarbons in Baiyun Sag, deep water area of Pearl River Mouth Basin. China Offshore Oil and Gas (in Chinese), 32(4): 36–45

|

|

Lyu Chengfu, Chen Guojun, Du Guichao, et al. 2014. Diagenesis and reservoir quality evolution of shelf-margin sandstones in Pearl River Mouth Basin, South China Sea. Journal of Petroleum Science and Technology, 4(1): 1–19

|

|

Lyu Chengfu, Chen Guojun, Zhang Gongcheng, et al. 2011. Reservoir characteristics of detrital sandstones in Zhuhai formation of Baiyun Sag, Pearl River Mouth Basin. Journal of Central South University (Science and Technology) (in Chinese), 42(9): 2763–2773

|

|

Ma Ming, Chen Guojun, Li Chao, et al. 2017. Quantitative analysis of porosity evolution and formation mechanism of good reservoir in Enping Formation, Baiyun Sag, Pearl River Mouth Basin. Natural Gas Geoscience (in Chinese), 28(10): 1515–1526

|

|

Mansurbeg H, El-ghali MAK, Morad S, et al. 2006. The impact of meteoric water on the diagenetic alterations in deep-water, marine siliciclastic turbidites. Journal of Geochemical Exploration, 89(1–3): 254–258

|

|

Meng Yi, Chen Ronghua, Zheng Yulong. 2002. Foraminifera in surface sediments of the Bering and Chukchi Seas and their sedimentary environment. Acta Oceanologica Sinica, 21(1): 67–76

|

|

Mi Lijun, He Min, Zhai Puqiang, et al. 2019. Integrated study on hydrocarbon types and accumulation periods of Baiyun Sag, deep water area of Pearl River Mouth Basin under the high heat flow background. China Offshore Oil and Gas (in Chinese), 31(1): 1–12

|

|

Mi Lijun, Liu Qiang, Liu Lifang, et al. 2022. Technology leads the way of carbon neutrality application of CNOOC. China Offshore Oil and Gas (in Chinese), 34(4): 1–15

|

|

Osborne M J, Swarbrick R E. 1997. Mechanisms for generating overpressure in sedimentary basins: a reevaluation. AAPG Bulletin, 81(6): 1023–1041

|

|

Pang Xiong, Chen Changmin, Peng Dajun, et al. 2008. Basic geology of Baiyun deep-water area in the northern South China Sea. China Offshore Oil and Gas (in Chinese), 20(4): 215–222

|

|

Pang Jiang, Luo Jinglan, Ma Yongkun, et al. 2019. Forming mechanism of ankerite in Tertiary reservoir of the Baiyun Sag, Pearl River Mouth Basin, and its relationship to CO2-bearing fluid activity. Acta Geologica Sinica (in Chinese), 93(3): 724–737

|

|

Pang Xiong, Ren Jianye, Zheng Jinyun, et al. 2018. Petroleum geology controlled by extensive detachment thinning of continental margin crust: A case study of Baiyun Sag in the deep-water area of northern South China Sea. Petroleum Exploration and Development, 45(1): 29–42. doi: 10.1016/S1876-3804(18)30003-X

|

|

Purvis K. 1995. Diagenesis of Lower Jurassic sandstones, Block 211/13 (Penguin Area), UK northern North Sea. Marine and Petroleum Geology, 12(2): 219–228. doi: 10.1016/0264-8172(95)92841-J

|

|

Shi Hesheng, He Min, Zhang Lili, et al. 2014. Hydrocarbon geology, accumulation pattern and the next exploration strategy in the eastern Pearl River Mouth Basin. China Offshore Oil and Gas (in Chinese), 26(3): 11–22

|

|

Tian Lixin, Zhang Zhongtao, Pang Xiong, et al. 2020. Characteristics of overpressure development in the mid-deep strata of Baiyun Sag and its new enlightenment in exploration activity. China Offshore Oil and Gas (in Chinese), 32(6): 1–11

|

|

Tong Xiaoguang, Zhang Guangya, Wang Zhaomeng, et al. 2014. Global oil and gas potential and distribution. Earth Science Frontiers (in Chinese), 21(3): 1–9

|

|

Wang Jin, Cao Yingchang, Liu Keyu, et al. 2016. Pore fluid evolution, distribution and water-rock interactions of carbonate cements in red-bed sandstone reservoirs in the Dongying Depression, China. Marine and Petroleum Geology, 72: 279–294. doi: 10.1016/j.marpetgeo.2016.02.018

|

|

Wang Xiaotao, Wang Tongshan, Li Yongxin, et al. 2015. Experimental study on the effects of reservoir mediums on crude oil cracking to gas. Geochimica (in Chinese), 44(2): 178–188

|

|

Yuan Peifang, Lu Huanyong, Zhu Zongqi, et al. 1996. Pyrolysis experiment of Eogene source rocks in Jiyang Depression. Chinese Science Bulletin (in Chinese), 41(8): 728–730

|

|

Zeng Qingbo, Chen Guojun, Zhang Gongcheng, et al. 2015. The shelf-margin delta feature and its significance in Zhuhai Formation of deep-water area, Pearl River Mouth Basin. Acta Sedimentologica Sinica (in Chinese), 33(3): 595–606

|

|

Zeng Zhiwei, Yang Xianghua, Zhu Hongtao, et al. 2017. Development characteristics and significance of large delta of Upper Enping Formation, Baiyun Sag. Earth Science (in Chinese), 42(1): 78–92

|

|

Zhang Li, Chen Shuhui. 2017. Reservoir property response relationship under different geothermal gradients in the eastern area of the Pearl River Mouth Basin. China Offshore Oil and Gas (in Chinese), 29(1): 29–38

|

|

Zhang Gongcheng, Feng Congjun, Yao Xingzong, et al. 2021. Petroleum geology in deepwater settings in a passive continental margin of a marginal sea: a case study from the South China Sea. Acta Geologica Sinica (English edition), 95(1): 1–20. doi: 10.1111/1755-6724.14621

|

|

Zhang Huolan, Pei Jianxiang, Zhang Yingzhao, et al. 2013. Overpressure reservoirs in the mid-deep Huangliu Formation of the Dongfang area, Yinggehai Basin, South China Sea. Petroleum Exploration and Development (in Chinese), 40(3): 284–293

|

|

Zhang Gongcheng, Yang Haizhang, Chen Ying, et al. 2014. The Baiyun Sag: A giant rich gas-generation sag in the deepwater area of the Pearl River Mouth Basin. Natural Gas Industry (in Chinese), 34(11): 11–25

|

|

Zhang Qin, Zhu Xiaomin, Chen Xiang, et al. 2010. Distribution of diagenetic facies and prediction of high-quality reservoirs in the Lower Cretaceous of the Tanzhuang Sag, the southern North China Basin. Oil & Gas Geology (in Chinese), 31(4): 472–480

|

|

Zhu Junzhang, Shi Hesheng, Pang Xiong, et al. 2008. Zhuhai Formation source rock evaluation and reservoired hydrocarbon source analysis in the deepwater area of Baiyun Sag, Pearl River Mouth Basin. China Offshore Oil and Gas (in Chinese), 20(4): 223–227

|

|

Zhu Ming, Zhang Xiangtao, Huang Yuping, et al. 2019. Source rock characteristics and resource potential in Pearl River Mouth Basin. Acta Petrolei Sinica (in Chinese), 40(S1): 53–68

|