| Citation: | Hongyue Wang, Zhongbo Wang, Yang Wang, Haiyan Tang, Xiaodong Zhang, Xiaofeng Luo, Yongxin Mai, Xuhong Huang, Yilin Zheng, Ping Yin, Zhongping Lai. Preliminary study on the depositional model in the wave-dominated delta evolution during the Anthropocene: a case study of the Hanjiang River Delta in China[J]. Acta Oceanologica Sinica, 2024, 43(11): 45-56. doi: 10.1007/s13131-024-2313-z |

Modern river deltas are sedimentary bodies resulting from terrigenous sediments under the combined actions of rivers, waves, and tides, which were mostly formed in the early Holocene (Renaud et al., 2013). Their development and evolution are closely linked to variations in both fluvial and marine processes, recording the interplay of terrestrial sediment delivery and reworking, destructive marine process and even neo-tectonic subsidence (Ericson et al., 2006; Syvitski, 2008; Bi et al., 2014). Due to unique geographical locations, the deltas also serve as major population center. Over the past century, more than 500 million people have inhabited in deltaic areas worldwide (Ericson et al., 2006; Woodroffe et al., 2006). The intensification of human activities, such as rapid industrialization and urbanization, have led to a transition from constructive stage to destructive stage in deltas (Day et al., 1995; McManus, 2002; Ericson et al., 2006; Szabo et al., 2016). Therefore, modern delta sediments not only recorded natural sedimentary processes, but also captured their response to human activities (Bianchi and Allison, 2009). Investigating the sedimentary evolution of modern deltas is crucial for promoting sustainable social development.

The classification of deltas is generally based on the dominant forces exerted by rivers and oceans, resulting in fluvial-dominated deltas, tide-dominated deltas, and wave-dominated deltas (Galloway, 1975). Wave-dominated deltas exhibit distinct coastal features such as estuarine sandbars, lagoons, barrier spits, and barrier islands due to the influence of wave action (Bhattacharya and Giosan, 2003; Anthony, 2015). Under the influence of wave action, estuarine sandbars evolve into barrier islands. Subsequently, the lagoon becomes filled with river sediment and connects to the barrier island, leading to a periodic seaward progradation of the delta (van Maren and Hoekstra, 2003; Anthony, 2015; Dominguez and Guimarães, 2021). Hence, the continual regeneration of barrier islands or spits plays a pivotal role in maintaining the cyclic evolution of the wave-dominated delta (Preoteasa et al., 2016), such as the Danube Delta (Vespremeanu-Stroe and Preoteasa, 2015), the Ba Lat Delta (van Maren and Hoekstra, 2003), and the Mekong Delta (Ta et al., 2002a, b). These wave-dominated deltas all exhibit multi-stage barrier spits at deltaic fronts, which result in periodic progradation towards the sea.

The fluctuation of sea level and the impact of climate change have been acknowledged as the primary driving forces influencing delta evolution (Milliman et al., 1989; Tsyban et al., 1990). However, during the Anthropocene, human activities have significantly affected the natural process of deltaic deposition (Syvitski et al., 2005; Milliman and Farnsworth, 2011). River engineering projects such as channel mining and dam construction, along with urbanization within deltas, now exert a dominant influence on their evolution (Syvitski et al., 2009; Brondizio et al., 2016; Nicholls et al., 2020). Reservoir construction is widely recognized as the foremost determinant in contemporary terrestrial sedimentary processes (Walling and Fang, 2003). Approximately one-third of terrestrial sediments become trapped due to dam and reservoir construction (Syvitski et al., 2005; Renaud et al., 2013). The combination of sediment reduction, isostatic loading factors, and sediment compaction further exacerbates delta erosion and subsidence (Ericson et al., 2006). For example, after the completion of the Aswan High Dam in 1964, the sediment flux of the Nile River was reduced to 0 t/a and its delta shoreline eroded at a rate of 143–160 m/a (Fanos, 1995; Frihy et al., 2003). The Hoa Binh Dam in the Red River induced a significant reduction by approximately 60%–70% in sediment flux (Woodroffe et al., 2006). As a result of dam constructions and riverbed mining activities, the coastlines of the Mekong Delta have experienced erosion on 64% of its length by 2015 (Li et al., 2017). This erosion surpasses the extent of accretion along the coastline, indicating a reversal of the previously consistent progradational pattern (Ta et al., 2002b; Besset et al., 2016; Li et al., 2017). Understanding the impact of human activities on delta evolution has consequently emerged as a prominent focal point within contemporary delta research (Ericson et al., 2006; Syvitski et al., 2009; Besset et al., 2019).

Over the past four decades, satellite remote sensing (SRS) technology has experienced rapid development and gradually emerged as one of the primary methodologies for studying the evolution of delta geomorphology due to its extensive coverage, convenient data acquisition, and relatively low cost (Zhao et al., 2008; Carvalho et al., 2020; Munasinghe et al., 2021). Zhu et al. (2013) employed SRS method to extract diverse categories of coastlines in the Zhujiang River (Pearl River) Delta during 1998 to 2003, revealing that anthropogenic activities drove coastline alterations. Similarly, the SRS analysis illustrated the impact of human activities on deltaic evolution by identification coastline changes of the Huanghe River (Yellow River) Delta during 1992–2014 (Wang, 2019). Chen et al. (2020) conducted a comprehensive assessment of the Irrawaddy Delta’s evolution using SRS technology and identified its influencing factors.

The barrier spits in wave-dominated deltas of small-rivers exhibit relatively large rates of morphological changes with short response time to wave or climate variations, as compared to large-river deltas (Petersen et al., 2008; Kaergaard and Fredsoe, 2013; Qi et al., 2021). They are more susceptible to variation of sediment supply, sea level fluctuation and climate changes (Postma, 1990). The Anthropocene, being a distinct epoch in geological time, has effectively facilitated the integration between contemporary processes and geological history, thereby assisting in the delineation of various stages in the evolutionary trajectory of modern delta sedimentation (Zalasiewicz et al., 2017; Wang, 2019). Barrier spits are assumed to play a key role in the development of wave-dominated deltas (Vespremeanu-Stroe and Preoteasa, 2015). The investigation of the depositional evolution of barrier systems under anthropogenic influences is crucial for understanding the variation in the deltaic evolution model during the Anthropocene.

The Hanjiang River Delta (HRD) is a representative wave-dominated delta of a small river situated in the northern region of the South China Sea (Li, 1987). At the estuary of the Hanjiang River (HR), there exists a characteristic barrier spit-lagoon sedimentary system. Due to the implementation of over 50 hydrodynamic-engineering projects since 1950, the sediment flux of the HR has been altered significantly (Zeng and Shao, 2002; Zhang, 2016). Therefore, HRD is an ideal subject for studying its sedimentary evolution under human influence in the Anthropocene, serving as a representative case of modern delta in the East Asian marginal seas. In this study, we employed SRS method to extract spatio-temporal variation of HRD and analyzed alternated sedimentary facies and strata of piston core sediments. This allows us to revisit the changes in the depositional model and its forcing mechanism in a wave-dominated delta under the human activities. The findings will contribute to enriching and enhancing the theory on depositional evolution of wave-dominated deltas.

The HR is situated in the southeastern region of China, spanning a length of 470 km, featuring an elevation drop of 920 m and encompassing a drainage area of 30 112 km2 (Li et al., 1987). The HRD is a wave-dominated delta, formed by the sedimentation of four downstream tributaries originating from Chaozhou, namely Yifengxi River, Nanxi River, Lianyang River, and Waisha River (Li et al., 1987, 2015). The delta, spanning a total area of 915.08 km2, extends from Zhuganshan in the south to Xikou-Yanhong in the north and Guxiang–Ganbishan in west, making it the second largest delta in Guangdong Province, China (Fig. 1).

The HRD is a block-type delta situated in the southeastern region of the Cathaysia block, controlled by the northeast (NE) faults (Shantou-Raoping Fault and Puning–Chao’an Fault) as well as the northwest (NW) faults (Hanjiang Fault, Chenghai–Gugang Fault, and Rongjiang Fault) (Zhang, 1983; Li et al., 1987). The Quaternary sediments extensively distributed within the delta plain, with a thickness ranging from 30 m to 120 m and an average thickness of about 75.4 m (Li et al., 1987). Since the late Holocene, the western and eastern edges of the delta have experienced continuous neo-tectonic uplift while the central region has undergone subsidence, facilitating the accumulation of delta sediments and landform development (Zeng and Shao, 2002).

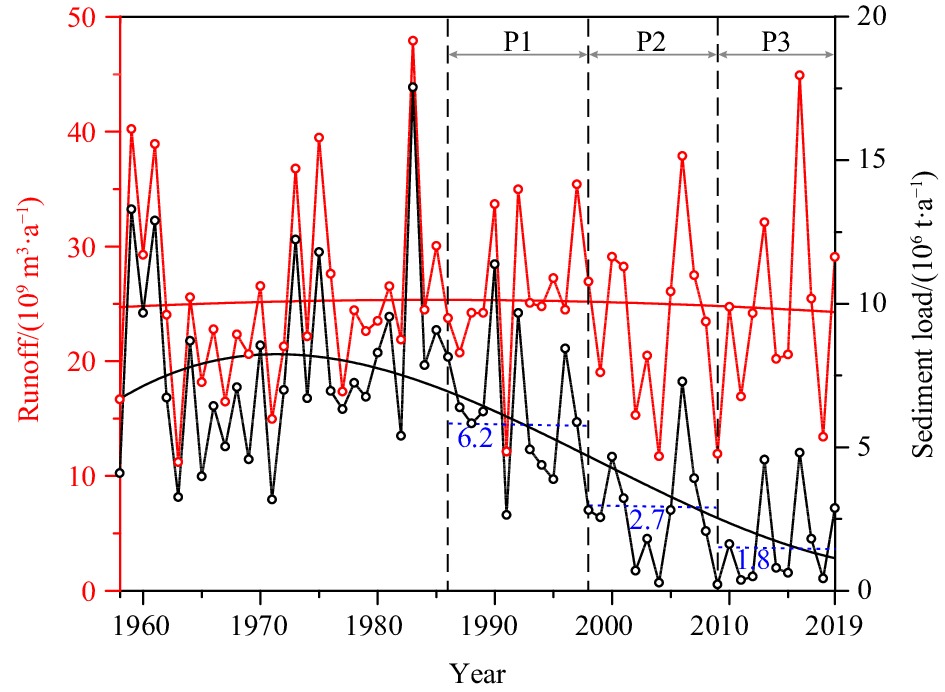

The prevailing winds in the vicinity of the HRD predominantly originate from the NE and south-southeast (SSE), with an average wind speed of 3.7 m/s and a maximum wind speed of 13.8 m/s (Lin et al., 2010). The primary wave direction is north-east-east (NEE), which veers towards south-east (SE) near the coast, exhibiting an average wave height of 1.1 m and a maximum height of 6.5 m (Li, 1986a, b). Within the region, the tides patterns are characterized by irregular semi-diurnal tides, with an average high water level of 0.53 m and an average tidal range of ca. 1.0 m (Wang, 2017). The length of the natural coastline in the HRD has decreased from 22.98 km in 1986 to 6.95 km in 2021, while the artificial coastline has increased from 10.11 km in 1986 to 25.93 km in 2021 (Fig. 1b). The runoff and sediment load of HR varied between 47.93 × 109 m3/a (1983) and 11.20 × 109 m3/a (1963) and 17.54 × 106 t/a (1983) and 0.22 × 106 t/a (2009) during 1958–2019, respectively (Fig. 2).

The study area is the barrier spit of the HRD, located in the north part of the Lianyang River Estuary (Fig. 1c), spanning approximately 3.6 km in length with a width ranging from 200 m to 400 m.

The SRS data was obtained from the Google Earth Engine cloud platform (Google Earth Engine:

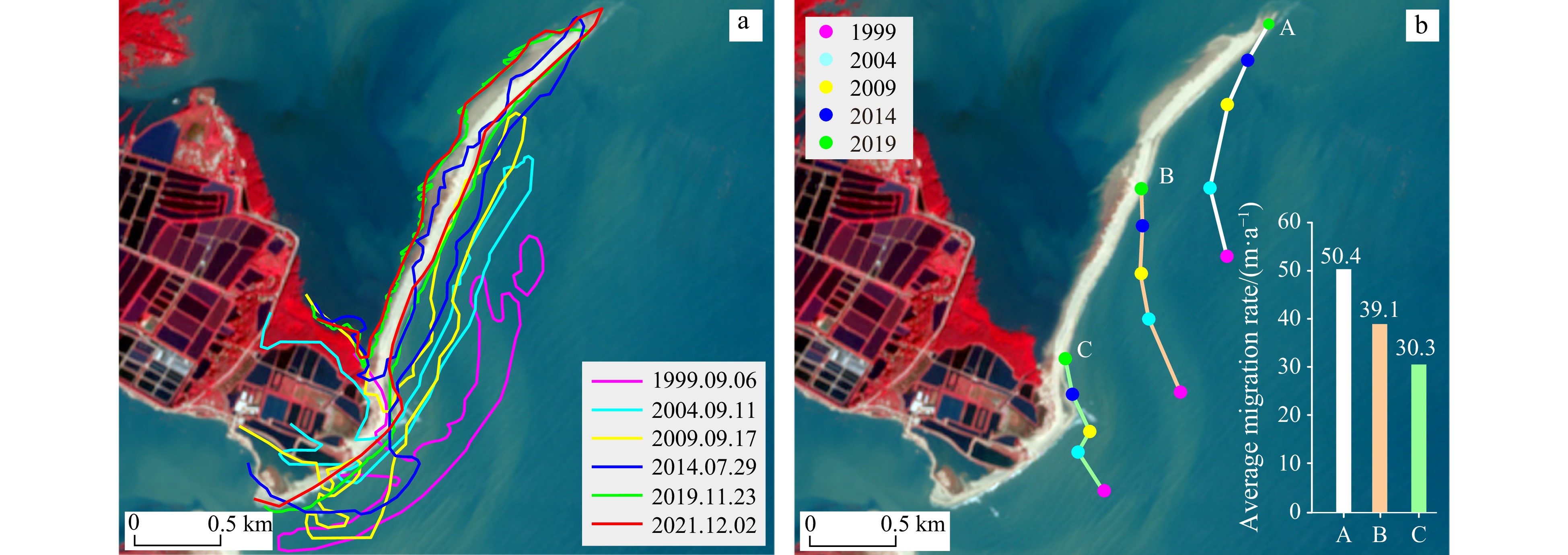

The accuracy of coastline extraction was improved by the application of coordinate normalization on remote sensing images obtained from various satellites using ArcGIS 10.7 software. The geographic coordinate system is CGCS2000 (China Geodetic Coordinate System 2000), and the projected coordinate system is CGCS2000 3 Degree GK CM 117 E. Geometric correction was performed on the images using road intersections as control points to obtain high-quality remote sensing images for visual interpretation of changes in coastline (Fig. 1b). The perimeter and area of the barrier spit were determined based on the imagery captured during high tide periods (Fig. 4). To ensure accurate coastline extraction, coordinate normalization was performed on remote sensing images obtained from different satellites. Shoreline change analysis was conducted using the selected remote sensing images during 1999 to 2019 at five-year intervals (Fig. 5).

The satellite imagery primarily captures the instantaneous waterline at the time of imaging (Chong, 2004). To determine the mean high tide level, tidal correction is required. Nevertheless, considering the limited tidal range in the study area (<1 m), the influence of tidal variation can be disregarded (Zhu and Zhang, 2023).

A total of eight piston boreholes were obtained on the barrier spit in August 2022. These boreholes were subsequently split, described, photographed and subsampled in the lab. The lithological description consists of color, texture, lithology, bioturbation intensity and sedimentary structure.

The subsamples were collected with intervals at 10 cm for grain size measurement, which were conducted at the Guangdong Provincial Key Laboratory of Marine Disaster Prediction and Prevention at Shantou University. The samples were treated with 10 ml of 30% H2O2 and 10 ml of 10% HCl to remove organic matter and carbonates respectively, and finally analyzed utilizing the Mastersizer

The regression analysis was respectively conducted based on the data of runoff and sediment load of HR since 1958 from Chao’an Hydrometric Station (Zhao, 2019) (Fig. 2).

Based on the analysis of SRS images during 1986 to 2021, three primary morphological types were identified in the barrier system of the HRD, including estuarine sandbar, barrier island with lagoon, and barrier spit (Fig. 3).

The estuarine sandbars were predominantly observed within the Lianyang River estuary between 1986 and 1992 (Fig. 3a), exhibiting spindle-shaped and conical forms (a3 in Fig. 3). Some of these sandbars experienced emergence or submergence due to tidal fluctuations.

Barrier islands developed out the river mouth during 1993–2009 (Fig. 3b). In 1999, the southern section of the barrier island became connected to the land (b2 in Fig. 3). Subsequently, several tidal inlets formed on the barrier island in 2006, which led to water exchange between lagoon and the ocean (b3 in Fig. 3). However, gradual obstruction occurred within those tidal inlets after 2008.

Barrier spits occurred between 2010 and 2021, manifesting as elongated slender landform extending in a northeast to the southwest direction (Fig. 3c). The southern part of the spit is connected to the land with no tidal inlets. Currently, the spit is undergoing a phase of stable development.

The comparison of perimeter and area variations in the HRD barrier system indicates a significant fluctuating growth trend during 1986 to 2021 (Fig. 4). The perimeter gradually increased from 3.43 km in 1986 to 8.15 km in 2021, demonstrating an average annual growth rate of 0.13 km/a. Similarly, the area progressively expanded progressively from 0.13 km2 in 1986 to 0.57 km2 in 2021, with an average growth rate of 0.01 km2/a. This process can be categorized into three distinct periods of rapid growth: Phase 1 (P1, 1986–1998), Phase 2 (P2, 1999–2009), and Phase 3 (P3, 2010–2021) (Fig. 4).

The average perimeters of the barrier system in these three stages are 4.00 km, 5.62 km, and 7.46 km respectively, with corresponding average areas of 0.19 km2, 0.27 km2, and 0.52 km2 (Fig. 4). Significant growth changes are observed in Phase 1 and Phase 2, with an increase from 0.13 km2 to 0.33 km2 and from 0.17 km2 to 0.31 km2 respectively, while it exhibits a relatively smaller change with an increase of 0.48 km2 to 0.57 km2 in Phase 3.

Notably, there was a sudden reduction in the area of the barrier system from 0.33 km2 in 1998 to 0.17 km2 in 1999 (Fig. 4), which can be attributed to the connection of the southern part of the barrier island to the mainland in 1999 (b2 in Fig. 3), subsequently diminishing sediment supply for the barrier development. Furthermore, an impressive expansion of the occurred, increasing from 0.31 km2 to 0.48 km2, due to the sudden surge in sediment flux during the period during 2009 to 2010, increasing from 0.22 × 106 t/a to 1.62 × 106 t/a (Figs 2 and 4). Subsequently, the development of the barrier system gradually reached a relatively stable stage (Fig. 4).

The shoreline changes of the barrier spit in a 5-year period reveals a consistent pattern of landward migration and northeastward extension during 1999 to 2021 (Fig. 5). The average landward migration rate is approximately 34.3 m/a, while the average growth rate in northward elongated direction exceeds 70 m/a (Fig. 5a). Different rates were observed in the northern, middle, and southern regions of the barrier system, with values of 50.4 m/a, 39.1 m/a, and 30.3 m/a respectively (Fig. 5b).

LY1 (0–104 cm): The sediments in this borehole are mainly composed of grayish-black clayey silts with a mean grain size (Mz value, Ф) ranging from 6 to 8. Bioturbation sporadically appears at the depths of 20–46 cm. At depths of 47–58 cm, distinct peaty layers interspersed with noticeable plant debris can be observed, suggesting deposition within a lagoon environment (Fig. 6).

LY2 (0–94 cm): The borehole is divided into two distinct parts by a scouring surface at depth of 35 cm. The upper sediments (0–35 cm) comprise yellow-brown sandy silts with occasional layers of gray-black silts and their Mz values (Ф) ranging from 2 to 4, indicating the deposition of sandy barrier spit facies. In contrast, the lower section of sediments (35–94 cm) consists of light gray-black clayey silts with shell fragments observed at the depth of 60 cm, and the Mz values (Ф) range from 6 to 8, suggesting lagoon deposits (Fig. 6).

LY3 (0–78 cm): The upper sediments (13–44 cm) are yellow-brown sandy silts with Mz values (Ф) of 2 to 4, indicating a sandy barrier spit. The middle sediments (44–64 cm) are light gray clayey silts with an average grain size Ф ranging from 6 to 8, suggesting a lagoon deposition. The lower sediments (64–78 cm) consist of yellow-brown sandy silts with an average grain size Ф ranging from 2 to 4. At the depth of 70–77 cm, there is a distinct layer of humus containing visible plant debris, interspersed with light gray sandy silt (Fig. 6).

LY4 (0–82 cm): The sediments are yellow-brown sandy silts, with the grain size gradually becoming finer upwards. The Mz values (Ф) range from 2 to 4, indicating a deposition of sandy spit facies. A layer of shell fragments is observed at a depth of 44–48 cm (Fig. 6).

LY5 (0–107 cm): The sediments are yellow-brown sandy silts with an average grain size (Ф) ranging from 2 to 4, indicating a deposition of sandy spit facies. Lots of shells fragments are present at the depths of 20–32 cm. Additionally, there is one 2 cm-thick layer composed of gray-black clayey silt at depths of 58 cm and 62 cm respectively (Fig. 6).

LY6 (0–124 cm): The sediments are composed of yellow-brown sandy silts with an average grain size (Ф) ranging from 2 to 4, indicating the deposition of sandy spit facies. Shell fragments are observed at depths of 45–58 cm and 90–124 cm (Fig. 6).

LY7 (0–96 cm): The sediments consist of yellow-brown sandy silts with an average grain size (Ф) of 2. They are aeolian deposition due to their significant sorting (Fig. 6).

LY8 (0–98 cm): The sediments are yellow brown to gray-black sandy silts with an average grain size (Ф) of 2. These deposits are the result of aeolian process and demonstrate good sorting characteristics. At depths of 16–20 cm, there exists a distinct layer consisting of clayey sandy silts with Mz value (Ф) of 7 (Fig. 6).

In summary, lithological characteristics of borehole LY1 reveal a deposition of lagoon facies (Fig. 6). The upper sediments in LY2 and LY3 correspond to barrier spit deposits, while the lower deposits belong to a lagoon facies (Fig. 6). In the remaining boreholes, the sediments exhibit features of barrier spit with thickness gradually increasing from south to north (ranging from 0.3 m in LY3 to 0.98 m in LY6). Based on comparison with their occurrence time in SRS images, it is inferred that the latest time of the transition from lagoon to barrier spit facies happened in 2009 (LY2), 2007 (LY3), 2010 (LY4), 2009 (LY5), 2017 (LY6–LY8), respectively (Figs 6 and 7). For instance, prior to 2009, LY2 exhibited deposition in lagoon facies (no barrier observed), followed by the subsequent spit deposition as evidenced by SRS images (Fig. 6). The vertical variation of sedimentary facies in different boreholes indicates a transition from lagoon to barrier spit, with the facies alteration across various locations suggesting the directional migration and evolution process of barrier spits from south to north. Additionally, the LY7 and LY8 sediments on the landward side exhibit a relatively uniform grain size composition [an average grain size (Ф) of 2] and well-sorted characteristics, indicating typical aeolian sand dune deposition in a barrier system (Fig. 6).

Based on temporal-spatial analysis of the HRD barrier system by SRS method (Figs 3–5) and borehole sedimentary facies (Fig. 6) in the present barrier spit, the evolution is composed of three stages: estuarine sandbar-barrier island stage (P1, 1986–1998); barrier island-lagoon stage (P2, 1999–2009); barrier spit stage (P3, 2010–2021) (Fig. 7).

The barrier system initially formed through the development of estuarine sandbars outside the HR estuary (Fig. 7, P1). In 1988, sandbars extensively developed underwater at the estuary (P1-b in Fig. 7). The continuous sediments supply from the HR (average of 5.94 × 106 t/a during 1986–1999) led to persistent accumulation of the estuary sandbar (Fig. 2). By 1994, an estuarine sandbar emerged and transformed into a barrier island (P1-c in Fig. 7).

In general, sandbars at the estuary of a delta tend to evolve into offshore barrier islands under the influence of waves and alongshore currents (Dan et al., 2011; Anthony, 2015; Vespremeanu-Stroe and Preoteasa, 2015). A parallel coastal estuarine barrier island has formed outside the HR estuary as a result of the combined influence of SE waves and NEE alongshore currents (Fig. 7). The position of the barrier island relatively shifted landward due to the relative decrease of HR sediment load (from 5.83 × 106 t/a in 1988 to 2.55 × 106 t/a in 1999) (Fig. 2). Simultaneously, there was an inclination for partial enclosure of water environment between the barrier island and coast (Fig. 7). Presently, the nearshore shallow marine environment is gradually transitioning into a lagoon environment located behind the barrier island.

The previous study has demonstrated that once sediment is exhausted and the barrier becomes source starvation, then wave climate starts to predominate with respect to shoreline readjustment (Orford et al., 1996). The sediment load of the HR experienced a rapid decline below 3 × 106 t/a during 1998 and 1999, resulting in a significant reduction in the area of the barrier system from 0.33 km2 to 0.17 km2 (Figs 2, 3, and 7). Due to the predominant role played by wave action, the barrier island continuously migrated landward. In 1999, this movement led to the formation of a semi-enclosed lagoon as southern barrier island moved towards the coast (P2-a in Fig. 7). From 2002 to 2004, there was relatively slow development of the barrier system due to the significant decrease in sediment flux of the HR (Figs 2 and 4).

It appears that extreme climate events are likely to be responsible for spit breaching and new inlets (Eric et al., 2014). On May 18, 2006, typhoon Chanchu, characterized by wind speeds exceeding 35 m/s, caused abrupt destruction to the barrier island resulting in the formation of tidal inlets with inlet delta (P2-c in Fig. 7), as a barrier island-lagoon system defined by Oertel (1985).

Compared to the barrier morphological variations identified by SRS analysis (Fig. 7), the transition from fine-grained lagoon deposits in gray-black color to coarse-grained sandy barrier island deposits in yellow-brown color in LY3 took place in 2007 (Figs 6, P2-3 in Fig. 7). Similarly, it can be inferred that the shift from lagoon deposits to sandy spit deposits in borehole LY2 occurred around 2009 (Fig. 6, P2-4 in Fig. 7). Specifically, due to the rotational landward migration of barrier spit (Qi et al., 2021), the conversion of sedimentary facies does not strictly adhere to a specific chronological sequence. For example, it is plausible that the transition time of sedimentary facies in LY3 borehole preceded than that in LY2 borehole (Figs 6 and 7).

When the reworking by waves exceeds sediment supply by the river, the barrier islands are transformed into a shore-parallel wave-dominated barrier-spit system (van Maren and Hoekstra, 2003). Since 2010, there has been a consistent and stable low sediment load in the HR, with a constant rate of 2×106 t/a (Fig. 2), leading to a weakened fluvial impact on delta deposition and intensified wave erosion. The tidal inlets have been become filled and obstructed, resulting in a barrier spit formation at the HR estuary (P3-a–P3-d in Figs 7). After 2014, due to wave-induced erosion, the original sediments of the southern barrier spit initiated to be transported towards the north by the NEE coastal currents to form the distal barrier spit (e.g., LY4, LY5, and LY6). The fine-grained sediments of the bottom lagoon were exposed as a result of erosion in upper sandy barrier sediments (e.g., LY1) (Figs 6 and 7). Consequently, the sediments comprising the growing northern barrier spit consist of not only fluvial sediments but also eroded sediments from the southern barrier islands. Currently, due to the significantly reduced sediment supply from HR, this barrier spit is gradually migrating landward (Figs 5 and 7). Ultimately, it will merge within the delta plain, completing the progradation of delta and initiating another barrier deposition system like the barrier spit of the Changhua River Delta (Qi et al., 2021).

The evolution of barrier systems is highly dynamic that is primarily influenced by natural factors, including sediment supply, waves, tides, sea level fluctuations, and neo-tectonic movements (Riggs et al., 1995; Bastos et al., 2012). While sea level changes and neo-tectonic movements have minimal impact on the century-scale evolution of barrier sedimentation, variations of sediment load and wave actions primary control the development of deltaic barrier systems (Orford et al., 1996).

In HRD, the barrier system was initially characterized by estuarine sandbars and barrier islands, indicating a dominant role of fluvial sedimentation during the initial phase (1986–1999). Subsequently, wave action and coastal currents took place the role due to a continuous decline in sediment supply from the HR (1999–2021). Notably, extreme climate events such as storm surges and typhoons induced short-term morphological changes and positional shifts in the barrier system (Vespremeanu-Stroe and Preoteasa, 2015; Cheng et al., 2020). The typhoon Chanchu (May 18, 2006) nearly decimated the entire HRD barrier spit, submerging more than 90% of the barrier which reformed two years later.

Intense human activities have significantly impacted the sedimentation of river deltas, primarily evidenced by the reduction in river sediments that sustain delta development due to extensive construction of reservoirs and dams (Dunn et al., 2019). This alteration directly affects the geomorphic evolution of wave-dominated deltas (Syvitski et al., 2005; Anthony, 2015). In the Nile River Delta, land reclamation projects have led to a continuous decline in the area of Manzala lagoon with an average reduction rate of 0.52 km2/a during 1922–1995 (Frihy et al., 2003). The constructions of Panjiakou and Daheiting reservoirs have resulted in a significant sediment load reduction of Luanhe River (from 20 × 106 t/a in 1929–1969 to 0.9 × 106 t/a in the 1980s), leading to substantial erosion of the estuary barrier island (retreat rate > 0.5 m/a), shrinkage of lagoons (1–2 m/a) (Wu et al., 2008).

The annual sediment load of the HR has exhibited consistent decrease from 17.54 × 106 t/a in 1983 to 0.22 × 106 t/a in 2009 (Fig. 2). This decline can be attributed to two primary factors, such as water engineering construction and soil erosion control (Zhang, 2016; Yang et al., 2017). The significant declines of sediment load of the HR have directly led to the development of the barrier system from estuarine sandbars to barrier islands-lagoons and barrier spits, while also resulting in a landward migration of the deposition center. Therefore, anthropogenic activities are primarily responsible for the contemporary sedimentary evolution of small wave-dominated deltas.

The depositional model of the HRD in the Holocene exhibits similarities to wave-dominated deltas such as the Mekong Delta (Stutz and Pilkey, 2002; Tamura et al., 2012), Danube Delta (Vespremeanu-Stroe and Preoteasa, 2015; Preoteasa et al., 2016), and Ba Lat Delta (van Maren and Hoekstra, 2003). In theory, three phases can be summarized in the classic deposition model of wave-controlled deltas (Zong, 1987; Li et al., 1988, 2015; van Maren, 2005; Preoteasa et al., 2016) (Fig. 8a).

(1) Phase 1: delta front platform with sandbars (a1 in Fig. 8a)

During this stage, the dominant role in delta formation is played by ample supply of river sediments, resulting in the development of a submerged platform morphology. Coarse-grained sediments accumulated at the estuary, forming underwater sandbars, while fine-grained sediments are transported relatively far seawards, contributing to pro-delta deposition (Preoteasa et al., 2016).

(2) Phase 2: formation of a barrier-spit system (a2 in Fig. 8a)

The continuous river sediment supply results in the gradual amalgamation of dispersed sandbars at the estuary through wave action, leading to the formation of barrier spits and the lagoons (Anthony, 2015). The newly-formed barrier island acts as a trap for fluvial and nearshore sourced sediments; it evolves through continuous downdrift elongation and landward migration (Preoteasa et al., 2016).

(3) Phase 3: back-barrier infilling (a3 in Fig. 8a)

When the lagoon has been entirely filled, having no accumulation space to trap more river-borne sediments. Those sediments are continuously transported and accumulated at the leading edge of the delta, resulting in the formation of a new depocenter (Phase 1). This indicates the initiation of a new barrier system and signifies the beginning of another developmental cycle in delta evolution (van Maren, 2005).

The deposition evolution of deltas primarily relies on the continuous and abundant supply of river sediments, as well as wave and tide action, neo-tectonic subsidence, and sea level fluctuation (Besset et al., 2019). However, human activities in the Anthropocene have induced alterations in sediment load and depositional environments, gradually modifying the evolutionary process of barrier system and subsequently influencing the depositional pattern of wave-dominated deltas (Stutz and Pilkey, 2001).

The landward migration of estuary depocenters under marine influences (waves, tides, costal currents), is a direct consequence of the continuous reduction in sediment loads from rivers (Simeoni et al., 2007). In the Po River Delta, the significant decrease in sediment load from the Po River (from 12.8 × 106 t/a in 1918–1943 to 4.7 × 106 t/a in 1986–1991) has led to the formation of new sandbars due to the shift in landward depocenter (Simeoni et al., 2007). The sediment deprivation (1940–2002) has decelerated the development of the downdrift depocenter of the southern barrier spit in the Danube Delta and caused a delay in the formation of secondary spits (Panin and Jipa, 2002; Preoteasa et al., 2016). In this study, the dramatic decline of sediment load of HR induced the landward migration of the delta front (Figs 2 and 7), resulting in variations of depositional process of barrier spits (Figs 5 and 8b). This founding aligns with the depositional pattern observed in the foreland barrier spit in the Changhua River Delta. The formation of the barrier spit occurred between 1985 and 2013, during which there was a significant reduction in sediment load from 131 × 106 t/a to 36 × 106 t/a. The barrier spit underwent rotational movement towards the mainland and experienced periodic cycles of 13 years (Qi et al., 2021).

Therefore, taking into account the influence of the human activities, we propose a modified depositional model for wave-dominated deltas in the Anthropocene based on the conceptual model (Vespremeanu-Stroe and Preoteasa, 2015; Preoteasa et al., 2016) (Fig. 8b).

(1) Phase 1: delta front platform with sandbars (b1 in Fig. 8b)

The deposition of this phase is primarily driven by fluvial processes, which exhibits similarities to the conceptual deposition pattern of wave-dominated deltas (a1 in Fig. 8a), including the presence of a delta front platform and estuarine sandbars (b1 in Fig. 8b).

(2) Phase 2: formation of a barrier-spit system (b2 in Fig. 8b)

In this phase, marine processes take place the dominate role of fluvial processes in the conceptual model. As a result of anthropogenic activities, the supply of river-borne sediments has consistently diminished, leading to the amalgamation of estuarine sandbars into barrier islands under wave action. These barrier islands subsequently migrate landward and form barrier spits and semi-enclosed lagoons. Consequently, sediments from rivers and eroded materials induced by waves from the original barrier spit are delivered through alongshore currents to replenish the barrier spit.

(3) Phase 3: landward migration of barrier spit (progradation of delta) (b3 Fig. 8b)

The barrier spits gradually migrate landward due to the continuous decrease of river-borne sediments, driven by the influence of waves and coastal currents, until they eventually merge with the delta plain, thereby facilitating delta progradation. Subsequently, river sediments accumulate at the river mouth to create new underwater sandbars (Phase 1), initiating the development of a new barrier system in wave-dominated delta.

Compared with the conceptual depositional model (Vespremeanu-Stroe and Preoteasa, 2015; Preoteasa et al., 2016), the modified model highlights the impact of human activities in the Anthropocene on sediment load of rivers. In this context, the marine processes dominate the depositional evolutionary pattern of barrier systems, which leads to the barrier migration towards the shoreline and seaward progradation of deltas. It can be inferred if sediments accumulation at estuary fail to sustain delta development, starvation will result in delta erosion. At present, the HRD has not reached this stage. Therefore, it will not be discussed further in this study.

(1) The SRS analysis of the HRD reveals distinct periodical morphological characteristics and spatial variations of estuarine sandbars, barrier islands-lagoons, and barrier spits from 1986 to 2021. Estuarine sandbars predominantly emerged between 1986 and 1992, exhibiting spindle-shape, conical and cake-shape. Barrier islands-lagoons appeared from 1993 to 2009 in a narrow northeast-southwest elongated configuration. Barrier spits primarily formed between 2010 and 2021 in a narrow northeast-southwest elongated shape, gradually stabilizing after 2010.

(2) The stratigraphy of boreholes on the HRD demonstrates a south-to-north transition from lagoon to lagoon-barrier spit and barrier spit in vertical lithology, thereby providing the contemporary evolutionary trajectory of barrier system within the HRD.

(3) The depositional evolution of the HRD barrier system can be categorized into three phases: estuarine sandbar-barrier island phase (1986–1998); barrier island-lagoon phase (1999–2009); and barrier spit phase (2010–2021). During the estuarine sandbar-barrier island phase, fluvial processes played a predominate role in the deposition of barriers. Subsequently, due to a sustained decline in river sediment load (17.84 × 106 t/a to 0.23 × 106 t/a, 1958–2019), wave action and alongshore current control the depositional processes.

(4) We propose a modified depositional model of barrier system in wave-dominated deltas during Anthropocene, which encompasses estuarine sandbars and delta front platforms, barrier island-lagoon formation and landward migration of barrier spits. In comparison to the conceptual model in the Holocene, this pattern highlights human-induced reduction in sediment load from rivers, which lead to a seaward deltaic progradation driven by barrier landward migration.

|

Anthony E J. 2015. Wave influence in the construction, shaping and destruction of river deltas: a review. Marine Geology, 361: 53–78, doi: 10.1016/j.margeo.2014.12.004

|

|

Bastos L, Bio A, Pinho J L S, et al. 2012. Dynamics of the Douro estuary sand spit before and after breakwater construction. Estuarine, Coastal and Shelf Science, 109: 53–69

|

|

Besset M, Anthony E J, Bouchette F. 2019. Multi-decadal variations in delta shorelines and their relationship to river sediment supply: an assessment and review. Earth-Science Reviews, 193: 199–219, doi: 10.1016/j.earscirev.2019.04.018

|

|

Besset M, Anthony E J, Brunier G, et al. 2016. Shoreline change of the Mekong River delta along the southern part of the South China Sea coast using satellite image analysis (1973–2014). Géomorphologie: Relief, Processus, Environment, 22(2): 137–146

|

|

Bhattacharya J P, Giosan L. 2003. Wave-influenced deltas: geomorphological implications for facies reconstruction. Sedimentology, 50(1): 187–210, doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3091.2003.00545.x

|

|

Bi Naishuang, Wang Houjie, Yang Zuosheng. 2014. Recent changes in the erosion–accretion patterns of the active Huanghe (Yellow River) delta lobe caused by human activities. Continental Shelf Research, 90: 70–78, doi: 10.1016/j.csr.2014.02.014

|

|

Bianchi T S, Allison M A. 2009. Large-river delta-front estuaries as natural “recorders” of global environmental change. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 106(20): 8085–8092

|

|

Brondizio E S, Foufoula-Georgiou E, Szabo S, et al. 2016. Catalyzing action towards the sustainability of deltas. Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability, 19: 182–194, doi: 10.1016/j.cosust.2016.05.001

|

|

Carvalho B C, Dalbosco A L P, Guerra J V. 2020. Shoreline position change and the relationship to annual and interannual meteo-oceanographic conditions in Southeastern Brazil. Estuarine, Coastal and Shelf Science, 235: 106582

|

|

Chen Dan, Li Xing, Saito Y, et al. 2020. Recent evolution of the Irrawaddy (Ayeyarwady) Delta and the impacts of anthropogenic activities: a review and remote sensing survey. Geomorphology, 365: 107231, doi: 10.1016/j.geomorph.2020.107231

|

|

Cheng Lin, Tian Hailan, Liu Xihan, et al. 2020. Variations and influencing factors of the barrier islands near the Luan River estuary in the past 44 years—A case study of the Loong Island in Tangshan. Marine Sciences (in Chinese), 44(6): 22–30

|

|

Chong A K. 2004. A case study on the establishment of shoreline position. Survey Review, 37(293): 542–551, doi: 10.1179/sre.2004.37.293.542

|

|

Dan S, Walstra D J R, Stive M J F, et al. 2011. Processes controlling the development of a river mouth spit. Marine Geology, 280(1−4): 116–129, doi: 10.1016/j.margeo.2010.12.005

|

|

Day J W, Pont D, Hensel P F, et al. 1995. Impacts of sea-level rise on deltas in the Gulf of Mexico and the Mediterranean: the importance of pulsing events to sustainability. Estuaries, 18(4): 636–647, doi: 10.2307/1352382

|

|

Dominguez J M L, Guimarães J K. 2021. Effects of Holocene climate changes and anthropogenic river regulation in the development of a wave-dominated delta: the São Francisco River (eastern Brazil). Marine Geology, 435: 106456, doi: 10.1016/j.margeo.2021.106456

|

|

Dunn F E, Darby S E, Nicholls R J, et al. 2019. Projections of declining fluvial sediment delivery to major deltas worldwide in response to climate change and anthropogenic stress. Environmental Research Letters, 14(8): 084034, doi: 10.1088/1748-9326/ab304e

|

|

Eric C, Florian O, Xavier B, et al. 2014. Control of wave climate and meander dynamics on spit breaching and inlet migration. Journal of Coastal Research, 70(sp1): 109–114

|

|

Ericson J P, Vörösmarty C J, Dingman S L, et al. 2006. Effective sea-level rise and deltas: causes of change and human dimension implications. Global and Planetary Change, 50(1/2): 63–82, doi: 10.1016/j.gloplacha.2005.07.004

|

|

Fanos A M. 1995. The impact of human activities on the erosion and accretion of the Nile Delta coast. Journal of Coastal Research, 11(3): 821–833

|

|

Frihy O E, Debes E A, El Sayed W R. 2003. Processes reshaping the Nile delta promontories of Egypt: pre- and post-protection. Geomorphology, 53(3/4): 263–279, doi: 10.1016/S0169-555X(02)00318-5

|

|

Galloway W E. 1975. Process framework for describing the morphologic and stratigraphic evolution of deltaic depositional systems. Houston: Houston Geological Society, 87–98

|

|

Kaergaard K, Fredsoe J. 2013. Numerical modeling of shoreline undulations part 2: varying wave climate and comparison with observations. Coastal Engineering, 75: 77–90, doi: 10.1016/j.coastaleng.2012.11.003

|

|

Li Chunchu. 1986a. Geomorphic characteristics of the harbor-coasts in South China. Acta Geographica Sinica (in Chinese), 41(4): 311–320

|

|

Li Pingri. 1986b. The shoreline evolution in the Hanjiang River Delta during the past 6000 years. Chinese Science Bulletin (in Chinese), 31(19): 1495–1499, doi: 10.1360/csb1986-31-19-1495

|

|

Li Pingri. 1987. The shoreline evolution and the development model of the Hanjiang River Delta during the past 6000 years. Geographical Research (in Chinese), 6(2): 1–13

|

|

Li Pingri, Huang Zhenguo, Zhang Zhongying, et al. 1987. Changes of sea level since Late Pleistocene in eastern Guangdong. Haiyang Xuebao (in Chinese), 9(2): 216–222

|

|

Li Pingri, Huang Zhenguo, Zong Yongqiang. 1988. New views on geomorphological development of the Hanjiang River Delta. Acta Geographica Sinica (in Chinese), 43(1): 19–34

|

|

Li Xing, Liu J P, Saito Y, et al. 2017. Recent evolution of the Mekong Delta and the impacts of dams. Earth-Science Reviews, 175: 1–17, doi: 10.1016/j.earscirev.2017.10.008

|

|

Li Xiaolu, Yu Xinghe, Tan Chengpeng, et al. 2015. Sedimentary evolution and sand-body distribution of Holocene period, barrier-coast delta, Chaoshan region. Acta Sedimentologica Sinica (in Chinese), 33(4): 706–712

|

|

Lin Miaoqing, Du Qinbo, Weng Wukun. 2010. Characteristics of strong wind in the past 40 years in Nan’ao county, Guangdong province. Journal of Meteorology and Environment (in Chinese), 26(4): 48–52

|

|

McManus J. 2002. Deltaic responses to changes in river regimes. Marine Chemistry, 79(3/4): 155–170, doi: 10.1016/S0304-4203(02)00061-0

|

|

Milliman J D, Broadus J M, Gable F. 1989. Environmental and economic implications of rising sea level and subsiding deltas: the Nile and Bengal examples. Ambio, 18(6): 340–345

|

|

Milliman J D, Farnsworth K L. 2011. River Discharge to the Coastal Ocean: A Global Synthesis. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 392

|

|

Munasinghe D, Cohen S, Gadiraju K. 2021. A review of satellite remote sensing techniques of river delta morphology change. Remote Sensing in Earth Systems Sciences, 4(1/2): 44–75, doi: 10.1007/s41976-021-00044-3

|

|

Nicholls R J, Adger W N, Hutton C W, et al. 2020. Deltas in the Anthropocene. Cham, Switzerland: Palgrave Macmillan Cham, 1–22

|

|

Oertel G F. 1985. The barrier island system. Marine Geology, 63(1−4): 1–18, doi: 10.1016/0025-3227(85)90077-5

|

|

Orford J D, Carter R W G, Jennings S C. 1996. Control domains and morphological phases in gravel-dominated coastal barriers of Nova Scotia. Journal of Coastal Research, 12(3): 589–604

|

|

Panin N, Jipa D. 2002. Danube River sediment input and its interaction with the north-western Black Sea. Estuarine, Coastal and Shelf Science, 54(3): 551–562

|

|

Petersen D, Deigaard R, Fredsøe J. 2008. Modelling the morphology of sandy spits. Coastal Engineering, 55(7/8): 671–684., doi: 10.1016/j.coastaleng.2007.11.009

|

|

Postma G. 1990. An analysis of the variation in delta architecture. Terra Nova, 2(2): 124–130, doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3121.1990.tb00052.x

|

|

Preoteasa L, Vespremeanu-Stroe A, Tătui F, et al. 2016. The evolution of an asymmetric deltaic lobe (Sf. Gheorghe, Danube) in association with cyclic development of the river-mouth bar: long-term pattern and present adaptations to human-induced sediment depletion. Geomorphology, 253: 59–73, doi: 10.1016/j.geomorph.2015.09.023

|

|

Qi Yali, Yu Qian, Gao Shu, et al. 2021. Morphological evolution of river mouth spits: wave effects and self-organization patterns. Estuarine, Coastal and Shelf Science, 262: 107567

|

|

Renaud F G, Syvitski J P M, Sebesvari Z, et al. 2013. Tipping from the Holocene to the Anthropocene: how threatened are major world deltas?. Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability, 5(6): 644–654

|

|

Riggs S R, Cleary W J, Snyder S W. 1995. Influence of inherited geologic framework on barrier shoreface morphology and dynamics. Marine Geology, 126(1−4): 213–234, doi: 10.1016/0025-3227(95)00079-E

|

|

Simeoni U, Fontolan G, Tessari U, et al. 2007. Domains of spit evolution in the Goro area, Po Delta, Italy. Geomorphology, 86(3/4): 332–348

|

|

Stutz M L, Pilkey O H. 2001. A review of global barrier island distribution. Journal of Coastal Research, (34): 15–22

|

|

Stutz M L, Pilkey O H. 2002. Global distribution and morphology of deltaic barrier island systems. Journal of Coastal Research, 36(sp1): 694–707

|

|

Syvitski J P M. 2008. Deltas at risk. Sustainability Science, 3(1): 23–32, doi: 10.1007/s11625-008-0043-3

|

|

Syvitski J P M, Kettner A J, Overeem I, et al. 2009. Sinking deltas due to human activities. Nature Geoscience, 2(10): 681–686, doi: 10.1038/ngeo629

|

|

Syvitski J P M, Vorosmarty C J, Kettner A J, et al. 2005. Impact of humans on the flux of terrestrial sediment to the global coastal ocean. Science, 308(5720): 376–380, doi: 10.1126/science.1109454

|

|

Szabo S, Brondizio E, Renaud F G, et al. 2016. Population dynamics, delta vulnerability and environmental change: comparison of the Mekong, Ganges–Brahmaputra and Amazon delta regions. Sustainability Science, 11(4): 539–554, doi: 10.1007/s11625-016-0372-6

|

|

Ta T K O, Nguyen V L, Tateishi M, et al. 2002a. Sediment facies and Late Holocene progradation of the Mekong River Delta in Bentre Province, southern Vietnam: an example of evolution from a tide-dominated to a tide- and wave-dominated delta. Sedimentary Geology, 152(3/4): 313–325, doi: 10.1016/S0037-0738(02)00098-2

|

|

Ta T K O, Nguyen V L, Tateishi M, et al. 2002b. Holocene delta evolution and sediment discharge of the Mekong River, southern Vietnam. Quaternary Science Reviews, 21(16/17): 1807–1819, doi: 10.1016/S0277-3791(02)00007-0

|

|

Tamura T, Saito Y, Nguyen V L, et al. 2012. Origin and evolution of interdistributary delta plains; insights from Mekong River delta. Geology, 40(4): 303–306, doi: 10.1130/G32717.1

|

|

Tsyban A V, Everett J T, Titus J G. 1990. World oceans and coastal zones. In: Tegart W, Sheldon G W, Griffiths D C, eds. Climate Change: the IPCC Impacts Assessment. Canberra, Australia: Australian Government Publishing Service, 1–28

|

|

van Maren D S. 2005. Barrier formation on an actively prograding delta system: the Red River Delta, Vietnam. Marine Geology, 224(1−4): 123–143, doi: 10.1016/j.margeo.2005.07.008

|

|

van Maren D S, Hoekstra P. 2003. Cyclic development of a wave dominated delta. In: Proceedings of Coastal Sediments’03. Corpus Christi: East Meets West Productions, 12

|

|

Vespremeanu-Stroe A, Preoteasa L. 2015. Morphology and the cyclic evolution of Danube delta spits. In: Randazzo G, Jackson D W T, Cooper J A G, eds. Sand and Gravel Spits. Cham, Switzerland: Springer, 327–339

|

|

Walling D E, Fang D. 2003. Recent trends in the suspended sediment loads of the world’s rivers. Global and Planetary Change, 39(1/2): 111–126, doi: 10.1016/S0921-8181(03)00020-1

|

|

Wang Muwang. 2017. Tidal level change of coastal of Hanjiang River Delta. Guangdong Water Resources and Hydropower (in Chinese), (11): 1–4

|

|

Wang Kuifeng. 2019. Evolution of Yellow River Delta coastline based on remote sensing from 1976 to 2014, China. Chinese Geographical Science, 29(2): 181–191, doi: 10.1007/s11769-019-1023-5

|

|

Woodroffe C D, Nicholls R J, Saito Y, et al. 2006. Landscape variability and the response of Asian megadeltas to environmental change. In: Harvey N, ed. Global Change and Integrated Coastal Management: The Asia-Pacific Region. Dordrecht: Springer, 277–314

|

|

Wu Sangyun, Geng Xiushan, Jin Yongde, et al. 2008. Evolution of lagoon system in the Jidong area and effect of human interference. Advances in Marine Science (in Chinese), 26(2): 190–199

|

|

Yang Chuanxun, Zhang Zhengdong, Zhang Qian, et al. 2017. Characteristics of multi-scale variability of water discharge and sediment load in the Hanjiang River during 1955–2012. Journal of South China Normal University (Natural Science Edition) (in Chinese), 49(3): 68–75

|

|

Zalasiewicz J, Waters C, Head M J. 2017. Anthropocene: its stratigraphic basis. Nature, 541(7637): 289–289

|

|

Zeng Qiang, Shao Rongsong. 2002. Geological environment and hazardous geological issues in the Hanjiang River Delta. The Chinese Journal of Geological Hazard and Control (in Chinese), 13(4): 91–93

|

|

Zhang Hunan. 1983. Tectonic activity and its impact on the formation and development of the Hanjiang River Delta. Haiyang Xuebao (in Chinese), 5(2): 202–211

|

|

Zhang Yupo. 2016. Analysis of sediment changes at the Chao’an Station on the main stream of the Han River. Science and Technology & Innovation (in Chinese), (15): 78–80

|

|

Zhang Xiaodong, Lu Zhiyong, Jiang Shenghui, et al. 2018a. The progradation and retrogradation of two newborn Huanghe (Yellow River) Delta lobes and its influencing factors. Marine Geology, 400: 38–48, doi: 10.1016/j.margeo.2018.03.006

|

|

Zhang Xiaodong, Wu Chuang, Zhang Yongchang, et al. 2022. Using free satellite imagery to study the long-term evolution of intertidal bar systems. Coastal Engineering, 174: 104123, doi: 10.1016/j.coastaleng.2022.104123

|

|

Zhang Xiaodong, Yang Zuosheng, Zhang Yexin, et al. 2018b. Spatial and temporal shoreline changes of the southern Yellow River (Huanghe) Delta in 1976–2016. Marine Geology, 395: 188–197, doi: 10.1016/j.margeo.2017.10.006

|

|

Zhao Lan. 2019. Characteristic Analysis of runoff and sediment at Chao’an Hydrometric Station in Hanjiang River Basin. Guangdong Water Resources and Hydropower (in Chinese), (1): 22–25

|

|

Zhao Bin, Guo Haiqiang, Yan Yaner, et al. 2008. A simple waterline approach for tidelands using multi-temporal satellite images: a case study in the Yangtze Delta. Estuarine, Coastal and Shelf Science, 77(1): 134–142

|

|

Zhu Junfeng, Wang Gengming, Zhang Jinlan, et al. 2013. Remote sensing investigation and recent evolution analysis of Pearl River delta coastline. Remote Sensing for Land and Resources (in Chinese), 25(3): 130–137

|

|

Zhu Xiaoyu, Zhang Yanpeng. 2023. The change analyses of shoreline in Jiangdong new distract and its adjacent region, Haikou. South China Geology (in Chinese), 39(1): 127–137

|

|

Zong Yongqiang. 1987. Developmental characteristics of the Han River Delta Landform. Chinese Science Bulletin (in Chinese), 32(22): 1734–1737, doi: 10.1360/csb1987-32-22-1734

|